Southern Railway (U.S.)

| |

| Reporting mark | SOU |

|---|---|

| Locale | Southern United States |

| Dates of operation | 1894–1990 |

| Successor | Norfolk Southern Railway (new name, 1990-Present) |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

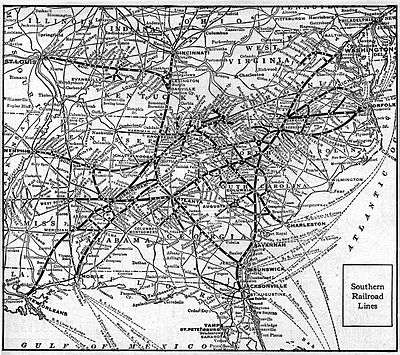

The Southern Railway (reporting mark SOU) (also known as Southern Railway Company) was a US class 1 railroad that was based in the Southern United States. It was the product of nearly 150 predecessor lines that were combined, reorganized and recombined beginning in the 1830s, formally becoming the Southern Railway in 1894.

At the end of 1970 Southern operated 6,026 miles (9,698 km) of railroad, not including its Class I subsidiaries AGS (528 miles or 850 km) CofG (1729 miles) S&A (167 miles) CNOTP (415 miles) GS&F (454 miles) and twelve Class II subsidiaries. That year Southern itself reported 26111 million net ton-miles of revenue freight and 110 million passenger-miles; AGS reported 3854 and 11, CofG 3595 and 17, S&A 140 and 0, CNO&TP 4906 and 0.3, and GS&F 1431 and 0.3

The railroad joined forces with the Norfolk and Western Railway (N&W) in 1982 to form the Norfolk Southern Corporation. The Norfolk Southern Corporation was created in response to the creation of the CSX Corporation (its rail system was later transformed to CSX Transportation in 1986). The Southern Railway was renamed Norfolk Southern Railway in 1990 and continued under that name ever since. Seven years later in 1997 the railroad absorbed the Norfolk and Western Railway, ending the Norfolk and Western's existence as an independent railroad.

History

Official Predecessors

- Richmond, York River and Chesapeake Railroad (1894)

- Richmond and Danville Railroad (1894)

- Memphis and Charleston Railroad (1894)

- East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railway (1894)

- Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway (1894)

Creation and independent status

The pioneering South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company, Southern's earliest predecessor line and one of the first railroads in the United States, was chartered in December 1827 and ran the nation's first regularly scheduled steam-powered passenger train – the wood-burning Best Friend of Charleston – over a six-mile section out of Charleston, South Carolina, on December 25, 1830. (The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad ran regular passenger service earlier that year.) By 1833, its 136-mile line to Hamburg, South Carolina, was the longest in the world.

As railroad fever struck other Southern states, networks gradually spread across the South and even across the Appalachian Mountains. By 1857 the Memphis and Charleston Railroad was completed to link Charleston, South Carolina, and Memphis, Tennessee, but rail expansion in the South was halted with the start of the Civil War. The Battle of Shiloh, the Siege of Corinth and the Second Battle of Corinth in 1862 were motivated by the importance of the Memphis and Charleston line, the only East-West rail link across the Confederacy. The Chickamauga Campaign for Chattanooga, Tennessee was also motivated by the importance of its rail connections to the Memphis and Charleston and other lines. Also in 1862 the Richmond and York River Railroad, which operated from the Pamunkey River at West Point, Virginia to Richmond, Virginia, was a major focus of George McClellan's Peninsular Campaign, which culminated in the Seven Days Battles and devastated the tiny rail link. Late in the war, the Richmond and Danville Railroad was the Confederacy's last link to Richmond, and transported Jefferson Davis and his cabinet to Danville, Virginia just before the fall of Richmond in April 1865.

Known as the "First Railroad War," the Civil War left the South's railroads and economy devastated. Most of the railroads, however, were repaired, reorganized and operated again. In the area along the Ohio River and Mississippi River, construction of new railroads continued throughout Reconstruction. The Richmond and Danville System expanded throughout the South during this period, but was overextended, and came upon financial troubles in 1893, when control was lost to financier J.P. Morgan, who reorganized it into the Southern Railway System.

Southern Railway came into existence in 1894 through the combination of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, the Richmond and Danville system and the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railroad. The company owned two-thirds of the 4,400 miles of line it operated, and the rest was held through leases, operating agreements and stock ownership. Southern also controlled the Alabama Great Southern and the Georgia Southern and Florida, which operated separately, and it had an interest in the Central of Georgia. Additionally, the Southern Railway also agreed to lease the North Carolina Railroad Company, providing a critical connection from Virginia to the rest of the southeast via the Carolinas.

Southern's first president, Samuel Spencer, drew more lines into Southern's core system. During his 12-year term, the railway built new shops at Spencer, North Carolina, Knoxville, Tennessee, and Atlanta, Georgia, built and upgraded tracks,[1][2] and purchased more equipment. He moved the company's service away from an agricultural dependence on tobacco and cotton and centered its efforts on diversifying traffic and industrial development. Spencer was killed in a train wreck in 1906.

After the line from Meridian, Mississippi, to New Orleans, Louisiana was acquired in 1916 under Southern's president Fairfax Harrison, the railroad had assembled the 8,000-mile, 13-state system that lasted for almost half a century. (SR itself operated 6791 miles of road at the end of 1925, but its flock of subsidiaries added 1000+ more.)

The Central of Georgia became part of the system in 1963, and the former Norfolk Southern Railway was acquired in 1974. Despite these small acquisitions, the Southern disdained the merger trend when it swept the railroad industry in the 1960s, choosing to remain a regional carrier. In 1978 President L. Stanley Crane[3][4] said the refusal to add routes through merger was a mistake, especially the decision not to add a connecting route to Chicago.

The Southern tried to gain access to Chicago by targeting the Monon Railroad and the Chicago and Eastern Illinois Railroad but both those railroads went to Southern's competitor, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad.[5] A decade later Crane tried to rectify the situation by merging with the Illinois Central Railroad.[6] When that failed, he petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to give Southern the old Monon routes and the old Atlantic Coast Line route from Jacksonville to Tampa by way of Orlando among other properties as a condition of the I.C.C.'s approval of the Seaboard Coast Line - Chessie System merger in 1979. While the request was supported by the I.C.C.'s Enforcement Bureau, it was ultimately unsuccessful.[7][8]

Becoming part of the Norfolk Southern Corporation

In response to the creation of the CSX Corporation in 1980, the Southern Railway joined forces with the Norfolk and Western Railway and formed the Norfolk Southern Corporation in 1980 which began operations in 1982, further consolidating railroads in the eastern half of the United States.

The Southern Railway was renamed Norfolk Southern Railway in 1990 and absorbed the Norfolk and Western Railway into its system in 1997. The railroad then acquired more than half of Conrail in 1999.

Notable features

Southern and its predecessors were responsible for many firsts in the industry. Starting in 1833, its predecessor, the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road, was the first to carry passengers, U.S. troops and mail on steam-powered trains,[9] and it was the first to operate at night.

On June 17, 1953, the railroad's last steam-powered freight train arrived in Chattanooga, Tennessee, behind 2-8-2 locomotive No. 6330.

From dieselization and shop and yard modernization, to computers and the development of special cars, the unit coal train and Radio Controlled Mid-Train Helper Locomotives, Southern often was on the cutting edge of change, earning the company its catch phrase, "Southern Gives a Green Light to Innovation".

In 1966, a popular steam locomotive excursion program was instituted under the presidency of W. Graham Claytor, Jr., and included Southern veteran locomotives such as Southern 630, Southern 722 and Southern 4501, along with non-Southern locomotives, such as Texas & Pacific 610, Canadian Pacific 2839 and Chesapeake & Ohio 2716. The steam program continued after the 1982 merger with the Norfolk and Western to form the Norfolk Southern, though increased operating costs and concerns ended the program in 1994. Norfolk Southern reinstated the steam program on a limited basis from 2011 to 2015, as the 21st Century Steam program.

In the early 2000s, a 22-mile (35 km) loop of former Southern Railway right-of-way encircling central Atlanta neighborhoods was acquired and is now the BeltLine trail.

Passenger trains

Along with its famed Crescent and Southerner, the Southern's other named trains included:[10]

- Aiken-Augusta Special

- Asheville Special

- Birmingham Special

- Carolina Special

- Florida Sunbeam

- Kansas City-Florida Special

- Peach Queen

- Pelican

- Piedmont Limited

- Ponce de Leon

- Queen and Crescent Limited

- Royal Palm

- Skyland Special

- Sunnyland

- Tennessean

Roads owned by the Southern Railway

- Alabama Great Southern Railroad (AGS)

- Albany and Northern Railway (A&N)

- Atlantic & Eastern Carolina Railway (A&EC)

- Birmingham Terminal Company

- Camp Lejeune Railroad Company

- Carolina and Northwestern Railway (C&NW)

- Central of Georgia Railway (CofG)(CG)

- Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway (CNO&TP)

- Chattanooga Station Company

- Chattanooga Traction Company (CTC)

- Georgia and Florida Railroad (G&F)

- Georgia Ashburn Sylvester and Camilla Railway (GAS&C)

- Georgia Northern Railway (GANO) — acquired in 1967

- Georgia Southern and Florida Railway (GS&F)

- Interstate Railroad (Int)

- Kentucky and Indiana Terminal Railroad (K&IT)

- Knoxville and Charleston Railroad

- Live Oak Perry and Gulf Railway (LOP&G)

- Louisiana Southern Railway (LS)

- New Orleans and North Eastern Railway (NO&NE)

- New Orleans Terminal Company (NOTCO)

- Norfolk Southern Railway Company (ORIGINAL "Short Line") (NS)

- Savannah & Atlanta Railway (SA)

- Saint John's River Terminal Company (SJRT)

- State University Railroad Company (54%)

- South Georgia Railway (SG)

- Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia Railway (TA&G)

- Tennessee Railway (Tenn)

Major railroad yards

- Chattanooga, Tennessee – DeButts Yard (formerly Citico Yard)

- Atlanta, Georgia – Inman Yard

- Spencer, North Carolina – Spencer YardTown of Spencer

- Birmingham, Alabama – Norris Yard

- Knoxville, Tennessee – Sevier Yard

- Macon, Georgia – Brosnan Yard

- Sheffield, Alabama – Sheffield Yard

- Alexandria, VA – Potomac Yard

Company officers

Presidents of the Southern Railway:

- Samuel Spencer (1894–1906)[11]

- William Finley (1906–1913)

- Fairfax Harrison (1913–1937)

- Earnest E. Norris (1937–1951)

- Harry A. deButts (1951–1962)

- D. William Brosnan (1962–1967)

- W. Graham Claytor, Jr. (1967–1977)[12][13]

- L. Stanley Crane[3][4] (1977–1980)

- Harold H. Hall (1980–1982)

See also

References

- ↑ "[Photograph of North Broad Curve of Southern Railroad, Toccoa, Stephens County, Georgia, 1908 Aug. 14]". Vanishing Georgia. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ Ferriday, E. C. (December 1918). "Double Tracking the Southern Railway". Cement and Engineering News. 30 (12). Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- 1 2 "NAE Website - Mr. L. Stanley Crane".

- 1 2 L. Stanley Crane (born in Cincinnati, 1915) raised in Washington, lived in McLean before moving to Philadelphia in 1981. He began his career with Southern Railway after graduating from The George Washington University with a chemical engineering degree in 1938. He worked for the railroad, except for a stint from 1959 to 1961 with the Pennsylvania Railroad, until reaching the company's mandatory retirement age in 1980. Crane went to Conrail in 1981 after a distinguished career that had seen him rise to the position of CEO at the Southern Railway. He died of pneumonia on July 15, 2003 at a hospice in Boynton Beach, Fla.

- ↑ http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1968/03/22/page/71/article/monon-l-n-roads-act-to-merge

- ↑ http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1978/07/05/page/69/article/southern-dreams-of-chicago

- ↑ The Miami News - Mar 20, 1979 page 5. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2206&dat=19790320&id=gQxgAAAAIBAJ&sjid=P-kFAAAAIBAJ&pg=2164,5708791&hl=en

- ↑ I.C.C. URGED TO SPLIT SEABOARD COAST LINE April 8, 1978 http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1978/04/08/110828112.html?pageNumber=29

- ↑ Brown, William H. (1871). "Chapter XXIX: Explosion of "Best Friend"". The History of the First Locomotives in America; From Original Documents And The Testimony Of Living Witnesses. New York: D. Appleton and Company. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- ↑ Schafer, Mike (2000). More Classic American Railroads. Osceola, WI: MBI. p. 156. ISBN 076030758X. OCLC 44089438.

- ↑ "The History of the railroad and Spencer". North Carolina Transportation Museum. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ↑ White, John H. Jr. (Spring 1986). "America's most noteworthy railroaders". Railroad History. 154: 9–15. ISSN 0090-7847. OCLC 1785797.

- ↑ quotes from article by journalist Don Phillips of the Washington Post in a "Tribute to W. Graham Claytor, Jr." published May, 1994

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Southern Railway (US). |

- Norfolk Southern company website

- Southern Railway Historical Association covers Southern Railway history

- Virginia Museum of Transportation located in Roanoke, VA

- Johnson's Depot: Railway History of Johnson City,TN

- Railroad lines abandoned by the Southern Railway

- Annual Report of Southern Railway Company in Mississippi (MUM00010) at The University of Mississippi.

- Harrison, Fairfax. A History of the Legal Development of the Railroad System of Southern Railway Company. Washington, D.C.: 1901. (A Google eBook)

- Norfolk Southern Railway. Retrieved February 22, 2005.

- Named Trains

- SOUTHERN Railfan

- Passenger Coach No. 3780 historical marker

Bibliography

- Murray, Tom. Southern Railway (MBI Railroad Color History). St. Paul: Voyageur Press, 2007. ISBN 0-7603-2545-6