Columbia, South Carolina

| Columbia, South Carolina | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State Capital | |||

| City of Columbia | |||

|

Skyline of downtown Columbia | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): "The Capital of Southern Hospitality", "Famously Hot", "Soda City", "The City of Dreams," "Paradise City," "Cola Town" | |||

|

Motto: Justitia Virtutum Regina (Latin) "Justice, the Queen of Virtues" | |||

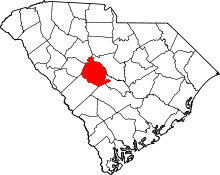

Location in Richland County and the state of South Carolina | |||

Columbia, SC Location in South Carolina | |||

| Coordinates: 34°0′2″N 81°2′5″W / 34.00056°N 81.03472°WCoordinates: 34°0′2″N 81°2′5″W / 34.00056°N 81.03472°W | |||

| Country | United States | ||

| State | South Carolina | ||

| County | Richland, Lexington | ||

| Approved | March 22, 1786 | ||

| Chartered (town) | 1805 | ||

| Chartered (city) | 1854 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Stephen K. Benjamin (D) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 134.9 sq mi (349 km2) | ||

| • Land | 132.2 sq mi (342 km2) | ||

| • Water | 2.7 sq mi (7 km2) 2% | ||

| Elevation[1] | 292 ft (89 m) | ||

| Population (2010) | |||

| • Total | 129,272 | ||

| • Estimate (2015) | 133,803 | ||

| • Rank | SC: 1st; US: 195th | ||

| • Density | 977.8/sq mi (377.5/km2) | ||

| • MSA (2015) | 810,068 (US: 71st) | ||

| • CSA (2015) | 937,288 (US: 58th) | ||

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | ||

| ZIP code(s) | 29201, 29203-6, 29209-10, 29212, 29223, 29225, 29229 | ||

| Area code(s) | 803 | ||

| FIPS code | 45-16000 | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 1245051[1] | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Columbia is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of South Carolina, with a population of 133,803 as of 2015.[2] The city serves as the county seat of Richland County, and a portion of the city extends into neighboring Lexington County. It is the center of the Columbia metropolitan statistical area, which had a population of 767,598 as of the 2010 United States Census, growing to 810,068 by July 1, 2015, according to 2015 U.S. Census estimates. The name Columbia was a poetic term used for the United States, originating from the name of Christopher Columbus.

The city is located approximately 13 miles (21 km) northwest of the geographic center of South Carolina, and is the primary city of the Midlands region of the state. It lies at the confluence of the Saluda River and the Broad River, which merge at Columbia to form the Congaree River. Columbia is home to the University of South Carolina, the state's flagship and largest university, and is also the site of Fort Jackson, the largest United States Army installation for Basic Combat Training. In 1860, the city was the location of the South Carolina Secession Convention, which marked the departure of the first state from the Union in the events leading up to the Civil War.

History

Early history

At the time of European encounter, the inhabitants of the area that became Columbia were a people called the Congaree.[3] In May 1540, a Spanish expedition led by Hernando de Soto traversed what is now Columbia while moving northward. The expedition produced the earliest written historical records of the area, which was part of the regional Cofitachequi chiefdom.[4]

From the creation of Columbia by the South Carolina General Assembly in 1786, the site of Columbia was important to the overall development of the state. The Congarees, a frontier fort on the west bank of the Congaree River, was the head of navigation in the Santee River system. A ferry was established by the colonial government in 1754 to connect the fort with the growing settlements on the higher ground on the east bank.[5]

Like many other significant early settlements in colonial America, Columbia is on the fall line from the Piedmont region. The fall line is the spot where a river becomes unnavigable when sailing upstream and where falling water downstream cannot power a mill.

State Senator John Lewis Gervais of the town of Ninety Six introduced a bill that was approved by the legislature on March 22, 1786, to create a new state capital. There was considerable argument over the name for the new city. According to published accounts, Senator Gervais said he hoped that "in this town we should find refuge under the wings of COLUMBIA", for that was the name which he wished it to be called. One legislator insisted on the name "Washington", but "Columbia" won by a vote of 11–7 in the state senate.

The site was chosen as the new state capital in 1786, due to its central location in the state. The State Legislature first met there in 1790. After remaining under the direct government of the legislature for the first two decades of its existence, Columbia was incorporated as a village in 1805 and then as a city in 1854.

Columbia received a large stimulus to development when it was connected in a direct water route to Charleston by the Santee Canal. This canal connected the Santee and Cooper rivers in a 22-mile-long (35 km) section. It was first chartered in 1786 and completed in 1800, making it one of the earliest canals in the United States. With increased railroad traffic, it ceased operation around 1850.

The commissioners designed a town of 400 blocks in a 2-mile (3 km) square along the river. The blocks were divided into lots of 0.5 acres (2,000 m2) and sold to speculators and prospective residents. Buyers had to build a house at least 30 feet (9.1 m) long and 18 feet (5.5 m) wide within three years or face an annual 5% penalty. The perimeter streets and two through streets were 150 feet (46 m) wide. The remaining squares were divided by thoroughfares 100 feet (30 m) wide. The width was determined by the belief that dangerous and pesky mosquitoes could not fly more than 60 feet (18 m) without dying of starvation along the way. Columbians still enjoy most of the magnificent network of wide streets.

The commissioners comprised the local government until 1797 when a Commission of Streets and Markets was created by the General Assembly. Three main issues occupied most of their time: public drunkenness, gambling, and poor sanitation.

As one of the first planned cities in the United States, Columbia began to grow rapidly. Its population was nearing 1,000 shortly after the start of the 19th century.

19th century

In 1801, South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) was founded in Columbia. The original building survives. The city was chosen as the site of the institution in part to unite the citizens of the Upcountry and the Lowcountry and to discourage the youth from migrating to England for their higher education. At the time, South Carolina sent more young men to England than did any other state. The leaders of South Carolina wished to monitor the progress and development of the school; for many years after the founding of the university, commencement exercises were held in December while the state legislature was in session.

Columbia received its first charter as a town in 1805. An intendant and six wardens would govern the town. John Taylor, the first elected intendant, later served in both houses of the General Assembly, both houses of Congress, and eventually as governor. By 1816, there were 250 homes in the town and a population of more than one thousand. Columbia became chartered as a city in 1854, with an elected mayor and six aldermen. Two years later, Columbia had a police force consisting of a full-time chief and nine patrolmen. The city continued to grow at a rapid pace, and throughout the 1850s and 1860s Columbia was the largest inland city in the Carolinas. Railroad transportation served as a significant cause of population expansion in Columbia during this time. Rail lines that reached the city in the 1840s primarily transported cotton bales, not passengers. Cotton was the lifeblood of the Columbia community; in 1850 virtually all of the city's commercial and economic activity was related to cotton.

"In 1830, approximately 1,500 slaves lived and worked in Columbia; this population grew to 3,300 by 1860. Some members of this large enslaved population worked in their masters' households. Masters also frequently hired out slaves to Columbia residents and institutions, including South Carolina College. Hired-out slaves sometimes returned to their owner's home daily; others boarded with their temporary masters."[6] During this period, "legislators developed state and local statutes to restrict the movement of urban slaves in hopes of preventing rebellion. Although various decrees established curfews and prohibited slaves from meeting and from learning to read and write, such rulings were difficult to enforce."[6] Indeed, "several prewar accounts note that many Columbia slaves were literate; some slaves even conducted classes to teach others to read and write." As well, "many slaves attended services at local Baptist, Presbyterian, and Methodist churches, yet some struggled to obtain membership in these institutions."[6]

Columbia's First Baptist Church hosted the South Carolina Secession Convention on December 17, 1860. The delegates drafted a resolution in favor of secession, 159–0. Columbia's location made it an ideal location for other conventions and meetings within the Confederacy.

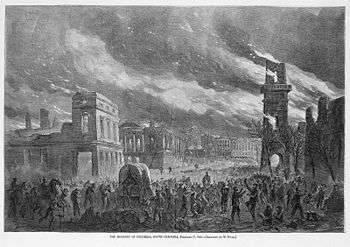

On February 17, 1865, in the last months of the Civil War, much of Columbia was destroyed by fire while being occupied by Union troops under the command of General William Tecumseh Sherman.[7] Jeff Goodwyn, mayor of Columbia, sent William B. Stanley and Thomas W. Radcliffe to surrender the city to Sherman's troops. According to legend, Columbia's First Baptist Church barely missed being torched by Sherman's troops. The soldiers marched up to the church and asked the sexton if he could direct them to the First Baptist Church. The sexton directed the men to the nearby Washington Street Methodist Church; thus, the historic landmark was saved from destruction by Union soldiers, and the sexton preserved his employment at the cost of another.[8]

Controversy surrounding the burning of the city started soon after the war ended. General Sherman blamed the high winds and retreating Confederate soldiers for firing bales of cotton, which had been stacked in the streets. General Sherman denied ordering the burning, though he did order militarily significant structures, such as the Confederate Printing Plant, destroyed. Firsthand accounts by local residents, Union soldiers, and a newspaper reporter offer a tale of revenge by Union troops for Columbia's and South Carolina's pivotal role in leading Southern states to secede from the Union. Today, tourists can follow the path General Sherman's army took to enter the city and see structures or remnants of structures that survived the fire.

During Reconstruction, Columbia became the focus of considerable attention. Reporters, journalists, travelers, and tourists flocked to South Carolina's capital city to witness a Southern state legislature whose members included former slaves. The city also made somewhat of a rebound following the devastating fire of 1865; a mild construction boom took place within the first few years of Reconstruction, and repair of railroad tracks in outlying areas created jobs for area citizens.

Following Reconstruction, the Columbia Music Festival Association (CMFA) was established in 1897,[9] by Mayor William McB. Sloan and the aldermen of the city of Columbia. It was headquartered in the Opera House on Main Street, which was also City Hall. Its role was to book and manage concerts and events in the opera house for the city.

20th century

The first few years of the 20th century saw Columbia emerge as a regional textile manufacturing center. In 1907, Columbia had six mills in operation: Richland, Granby, Olympia, Capital City, Columbia, and Palmetto. Combined, they employed over 3,400 workers with an annual payroll of $819,000, giving the Midlands an economic boost of over $4.8 million. Columbia had no paved streets until 1908, when 17 blocks of Main Street were surfaced. There were, however, 115 publicly maintained street crossings at intersections to keep pedestrians from having to wade through a sea of mud between wooden sidewalks. As an experiment, Washington Street was once paved with wooden blocks. This proved to be the source of much local amusement when they buckled and floated away during heavy rains. The blocks were replaced with asphalt paving in 1925.

The years 1911 and 1912 were something of a construction boom for Columbia, with $2.5 million worth of construction occurring in the city. These projects included the Union Bank Building at Main and Gervais, the Palmetto National Bank, a shopping arcade, and large hotels at Main and Laurel (the Jefferson) and at Main and Wheat (the Gresham). In 1917, the city was selected as the site of Camp Jackson, a U.S. military installation which was officially classified as a "Field Artillery Replacement Depot". The first recruits arrived at the camp on September 1, 1917.

In 1930, Columbia was the hub of a trading area with approximately 500,000 potential customers. It had 803 retail establishments, 280 of them being food stores. There were also 58 clothing and apparel outlets, 57 restaurants and lunch rooms, 55 filling stations, 38 pharmacies, 20 furniture stores, 19 auto dealers, 11 shoe stores, nine cigar stands, five department stores and one book store. Wholesale distributors located within the city numbered 119, with one-third of them dealing in food.

In 1934, the federal courthouse at the corner of Main and Laurel streets was purchased by the city for use as City Hall. Built of granite from nearby Winnsboro, Columbia City Hall is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Designed by Alfred Built Millet, President Ulysses S. Grant's federal architect, the building was completed in 1876. Millet, best known for his design of the Executive Office Building in Washington, D.C., had originally designed the building with a clock tower. Large cost overruns probably caused it to be left out. Copies of Mullet's original drawings can be seen on the walls of City Hall alongside historic photos of Columbia's beginnings. Federal offices were moved to the J. Bratton Davis United States Bankruptcy Courthouse.

Reactivated Camp Jackson became Fort Jackson in 1940, giving the military installation the permanence desired by city leaders at the time. The fort was annexed into the city in the fall of 1968, with approval from the Pentagon. In the early 1940s, shortly after the attacks on Pearl Harbor which began America's involvement in World War II, Lt. Colonel Jimmy Doolittle and his group of now-famous pilots began training for the Doolittle Raid over Tokyo at what is now Columbia Metropolitan Airport.[10] They trained in B-25 Mitchell bombers, the same model as the plane that now rests at Columbia's Owens Field in the Curtiss-Wright hangar. [11] The area's population continued to grow during the 1950s, having experienced a 40 percent increase from 186,844 to 260,828, with 97,433 people residing within the city limits of Columbia.

The 1940s saw the beginning of efforts to reverse Jim Crow laws and racial discrimination in Columbia. In 1945, a federal judge ruled that the city's black teachers were entitled to equal pay to that of their white counterparts. However, in years following, the state attempted to strip many blacks of their teaching credentials. Other issues in which the blacks of the city sought equality concerned voting rights and segregation (particularly regarding public schools). On August 21, 1962, eight downtown chain stores served blacks at their lunch counters for the first time. The University of South Carolina admitted its first black students in 1963; around the same time, many vestiges of segregation began to disappear from the city, blacks attained membership on various municipal boards and commissions, and a non-discriminatory hiring policy was adopted by the city. These and other such signs of racial progress helped earn the city the 1964 All-America City Award for the second time (the first being in 1951), and a 1965 article in Newsweek magazine lauded Columbia as a city that had "liberated itself from the plague of doctrinal apartheid."

Historic preservation has played a significant part in shaping Columbia into the city that it is today. The historic Robert Mills House was restored in 1967, which inspired the renovation and restoration of other historic structures such as the Hampton-Preston House and homes associated with President Woodrow Wilson, Maxcy Gregg, Mary Boykin Chesnut, and noted free black Celia Mann. In the early 1970s, the University of South Carolina initiated the refurbishment of its "Horseshoe". Several area museums also benefited from the increased historical interest of that time, among them the Fort Jackson Museum, the McKissick Museum on the campus of the University of South Carolina, and most notably the South Carolina State Museum, which opened in 1988.

Mayor Kirkman Finlay, Jr., was the driving force behind the refurbishment of Seaboard Park, now known as Finlay Park, in the historic Congaree Vista district, as well as the compilation of the $60 million Palmetto Center package, which gave Columbia an office tower, parking garage, and the Columbia Marriott, which opened in 1983. The year 1980 saw the Columbia metropolitan population reach 410,088, and in 1990 this figure had hit approximately 470,000.

Recent history

The 1990s and early 2000s saw revitalization in the downtown area. The Congaree Vista district along Gervais Street, once known as a warehouse district, became a thriving district of art galleries, shops, and restaurants. The Colonial Life Arena (formerly known as the Colonial Center) opened in 2002, and brought several big-named concerts and shows to Columbia. EdVenture, the largest children's museum in the Southeast, opened in 2003. The Columbia Metropolitan Convention Center opened in 2004, and a new convention center hotel opened in September 2007. A public-private City Center Partnership has been formed to implement the downtown revitalization and boost downtown growth. Mayor Stephen K. Benjamin started his first term in July 2010, and is the first black mayor in the city's history. Founders Park, home of USC baseball, opened in 2009. The South Carolina Gamecocks baseball team won two National Championships in 2010 and in 2011. The 2010 South Carolina Gamecocks football team, under coach Steve Spurrier, earned their first appearance in the SEC Championship. A Mast General Store was opened in 2011. On July 10, 2015, the Confederate battle flag was removed from the South Carolina State House grounds after being moved to the Confederate monument in 2000. The fallout from the historic flooding in October 2015 forced the South Carolina Gamecocks football team to move their October 10 home game. Spirit Communications Park, home of the Columbia Fireflies, opened in April 2016.

Geography and climate

One of Columbia's more prominent geographical features is its fall line, the boundary between the upland Piedmont region and the Atlantic Coastal Plain, across which rivers drop as falls or rapids. Columbia grew up at the fall line of the Congaree River, which is formed by the convergence of the Broad River and the Saluda River. The Congaree was the farthest inland point of river navigation. The energy of falling water also powered Columbia's early mills. The city has capitalized on this location which includes three rivers by christening itself "The Columbia Riverbanks Region". Columbia is located roughly halfway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Blue Ridge Mountains and sits at an elevation of around 292 ft (89 m).[12]

Soils in Columbia are well drained in most cases, with grayish brown loamy sand topsoil. The subsoil may be yellowish red sandy clay loam (Orangeburg series), yellowish brown sandy clay loam (Norfolk series), or strong brown sandy clay (Marlboro series). All belong to the Ultisol soil order.[13][14][15][16]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 134.9 square miles (349.5 km2), of which 132.2 square miles (342.4 km2) is land and 2.7 square miles (7.0 km2) is water (2.01%). Approximately ⅔ of Columbia's land area, 81.2 square miles (210 km2), is contained within the Fort Jackson Military Installation, much of which consists of uninhabited training grounds. The actual inhabited area for the city is slightly more than 50 square miles (130 km2).[2]

Columbia has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with mild winters, early springs, warm autumns, and very hot and humid summers. The area averages 53 nights below freezing, but extended cold or days where the temperature fails to rise above freezing are both rare.[17] With an annual average of 5.4 days with 100 °F (38 °C)+ and 77 days with 90 °F (32 °C)+ temperatures,[17] the city's current promotional slogan describes Columbia as "Famously Hot".[18] Precipitation, at 44.6 inches (1,130 mm) annually, peaks in the summer months, and is the least during spring and fall.[17] Snowfall averages 1.5 inches (3.8 cm), but many years receive no snowfall.[17] Like much of the southeastern U.S., the city is prone to inversions, which trap ozone and other pollutants over the area.

Official extremes in temperature have ranged from 109 °F (43 °C) on June 29 and 30, 2012 down to −2 °F (−19 °C), set on February 14, 1899, although a close second of −1 °F (−18 °C) was recorded on January 21, 1985, and the University of South Carolina campus reached 113 °F (45 °C) on June 29, 2012, establishing a new state record high.[17][19]

| Climate data for Columbia, South Carolina (Columbia Airport), 1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1887–present[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

84 (29) |

93 (34) |

96 (36) |

101 (38) |

109 (43) |

107 (42) |

107 (42) |

106 (41) |

101 (38) |

90 (32) |

83 (28) |

109 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 73.7 (23.2) |

77.6 (25.3) |

83.9 (28.8) |

89.3 (31.8) |

94.0 (34.4) |

98.5 (36.9) |

100.2 (37.9) |

98.9 (37.2) |

94.5 (34.7) |

88.2 (31.2) |

80.9 (27.2) |

75.3 (24.1) |

101.6 (38.7) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 56.0 (13.3) |

60.3 (15.7) |

68.2 (20.1) |

76.3 (24.6) |

83.8 (28.8) |

90.0 (32.2) |

92.7 (33.7) |

90.7 (32.6) |

85.2 (29.6) |

76.1 (24.5) |

67.3 (19.6) |

58.2 (14.6) |

75.4 (24.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 33.7 (0.9) |

36.8 (2.7) |

43.0 (6.1) |

50.4 (10.2) |

59.5 (15.3) |

68.2 (20.1) |

71.6 (22) |

71.0 (21.7) |

64.2 (17.9) |

52.1 (11.2) |

42.3 (5.7) |

35.3 (1.8) |

52.3 (11.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 16.4 (−8.7) |

20.6 (−6.3) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

33.2 (0.7) |

44.1 (6.7) |

56.6 (13.7) |

63.5 (17.5) |

62.0 (16.7) |

49.0 (9.4) |

34.4 (1.3) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

19.1 (−7.2) |

14.7 (−9.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −1 (−18) |

−2 (−19) |

4 (−16) |

26 (−3) |

34 (1) |

44 (7) |

54 (12) |

53 (12) |

40 (4) |

23 (−5) |

12 (−11) |

4 (−16) |

−2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.58 (90.9) |

3.61 (91.7) |

3.73 (94.7) |

2.62 (66.5) |

2.97 (75.4) |

4.69 (119.1) |

5.46 (138.7) |

5.26 (133.6) |

3.54 (89.9) |

3.17 (80.5) |

2.74 (69.6) |

3.22 (81.8) |

44.59 (1,132.6) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.8 (2) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.1 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.3) |

1.5 (3.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.9 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 10.5 | 11.8 | 10.5 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 9.0 | 106.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.2 | 65.8 | 64.6 | 62.1 | 68.2 | 70.8 | 73.4 | 76.5 | 75.9 | 73.0 | 71.6 | 70.7 | 70.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 172.7 | 180.7 | 237.3 | 269.6 | 292.9 | 280.0 | 286.0 | 263.3 | 239.8 | 235.0 | 193.8 | 175.0 | 2,826.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 55 | 59 | 64 | 69 | 68 | 65 | 65 | 63 | 64 | 67 | 62 | 57 | 64 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961−1990)[17][20][21] | |||||||||||||

Metropolitan area

The metropolitan statistical area of Columbia is the second-largest in South Carolina; it has a population of 810,068 according to the 2015 Census estimates.

Columbia's metropolitan counties include:

Columbia's suburbs and environs include:

- St. Andrews, Richland County: Pop. 20,493 (unincorporated)

- Seven Oaks, Lexington County: Pop. 15,144 (unincorporated)

- Lexington: Pop. 17,870 (on Lake Murray)

- Dentsville, Richland County: Pop. 14,062 (unincorporated)

- West Columbia: Pop. 14,988

- Cayce, Lexington County: Pop. 12,528

- Irmo: Pop. 11,097 (partly on Lake Murray)

- Forest Acres: Pop. 10,361

- Woodfield, Richland County: Pop. 9,303 (unincorporated)

- Red Bank, Lexington County: Pop. 9,617 (unincorporated)

- Oak Grove, Lexington County: Pop.10,291 (unincorporated)

- Camden, Kershaw County: Pop. 6,838

- Lugoff, Kershaw County: Pop. 7,434 (unincorporated)

- Ballentine: Pop. 2,500 (on Lake Murray)

- White Rock (on Lake Murray)

- Chapin: Pop. 1,445 (on Lake Murray)

Neighborhoods

- Allen Benedict Court

- Arsenal Hill

- Ashley Hall

- Ashley Place

- Belvedere

- Bluff Estates

- Booker Washington Heights

- Brookstone

- Brandon Hall

- Colonial Heights

- Colonial Park

- Colony

- Congaree Vista

- Cottontown/Bellevue Historic District

- Crane Forest

- Earlewood

- Eau Claire

- Elmwood Park

- Five Points

- Forest Acres

- Forest Hills

- Gable Oaks

- Granby Mill Village

- Greenview

- Gregg Park

- Gonzales Gardens

- Hastings Pointe

- Harbison

- Heathwood

- Heritage Woods

- Highland Park

- Hollywood-Rose Hill

- Hollywood Hills

- Keenan Terrace

- Killian

- King's Grant

- Lake Carolina

- Lake Katherine

- Lincolnshire

- Long Creek Plantation

- Magnolia Hall

- Martin Luther King (Valley Park)

- Melrose Heights

- Old Shandon

- Old Woodlands

- Olympia Mill Village

- Pinehurst

- Robert Mills Historic Neighborhood

- Rockgate

- Rosewood

- Sherwood Forest

- Shandon

- The Summit

- Summerhill

- Spring Valley

- University Hill

- Wales Garden

- Historic Waverly

- Villages at Longtown

- Wheeler Hill

- WildeWood

- Winchester

- Winslow

- Winterwood

- Woodcreek Farms

- Woodlake

- The Woodlands

- Yorkshire

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1830 | 3,310 | — | |

| 1840 | 4,340 | 31.1% | |

| 1850 | 6,060 | 39.6% | |

| 1860 | 8,052 | 32.9% | |

| 1870 | 9,298 | 15.5% | |

| 1880 | 10,036 | 7.9% | |

| 1890 | 15,353 | 53.0% | |

| 1900 | 21,108 | 37.5% | |

| 1910 | 26,319 | 24.7% | |

| 1920 | 37,524 | 42.6% | |

| 1930 | 51,581 | 37.5% | |

| 1940 | 62,396 | 21.0% | |

| 1950 | 86,914 | 39.3% | |

| 1960 | 97,433 | 12.1% | |

| 1970 | 112,542 | 15.5% | |

| 1980 | 101,208 | −10.1% | |

| 1990 | 98,052 | −3.1% | |

| 2000 | 116,278 | 18.6% | |

| 2010 | 129,272 | 11.2% | |

| Est. 2015 | 133,803 | [22] | 3.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23] 2015 Estimate[2] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 129,272 people, 52,471 total households, and 22,638 families residing in the city. The population density was 928.6 people per square mile (358.5/km²). There were 46,142 housing units at an average density of 368.5 per square mile (142.3/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 51.27% White, 42.20% Black, 2.20% Asian, 0.25% Native American, 0.30% Pacific Islander, 1.50% from other races, and 2.00% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.30% of the population.

There were 45,666 households out of which 22.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 28.7% were married couples living together, 17.1% have a female householder with no husband present, and 50.4% were nonfamilies. 38.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.18 and the average family size was 2.94.

In the city the population was spread out with 20.1% under the age of 18, 22.9% from 18 to 24, 30.1% from 25 to 44, 16.6% from 45 to 64, and 10.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29 years. For every 100 females there were 96.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,141, and the median income for a family was $39,589. Males had a median income of $30,925 versus $24,679 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,853. About 17.0% of families and 22.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.7% of those under the age of 18 and 16.9% ages 65 or older.

Religion

The Southern Baptist Convention has 241 congregations and 115,000 members. The United Methodist Church has 122 congregations and 51,000 members. The Evangelical Lutheran Church has 71 congregations and 25,400 members. The PC (USA) has 34 congregations and 15,000 members; the Presbyterian Church in America has 22 congregations and 8,000 members. The Catholic Church has 14 parishes. There are 3 Jewish synagogues. Muslims are served by the Islamic Center of Columbia, South Carolina.

Economy

Columbia enjoys a diversified economy, with the major employers in the area being South Carolina state government, the Palmetto Health hospital system, Blue Cross Blue Shield of South Carolina, Palmetto GBA, and the University of South Carolina. The corporate headquarters of Fortune 1000 energy company, SCANA, are located in the Columbia suburb of Cayce. Other major employers in the Columbia area include Computer Sciences Corporation, Fort Jackson, the U.S. Army's largest and most active initial entry training installation,[24] Richland School District One, Humana/TriCare, and the United Parcel Service, which operates its Southeastern Regional Hub at the Columbia Metropolitan Airport. Major manufacturers such as Square D, CMC Steel, Spirax Sarco, Michelin, International Paper, Pirelli Cables, Honeywell, Westinghouse Electric, Harsco Track Tech, Trane, Intertape Polymer Group, Union Switch & Signal, FN Herstal, Solectron, and Bose Technology have facilities in the Columbia area. There are over 70 foreign affiliated companies and fourteen Fortune 500 companies in the region. The gross domestic product (GDP) of the Columbia metropolitan statistical area as of 2010 was $31.97 billion, the highest among MSAs in the state.[25]

Several companies have their global, continental, or national headquarters in Columbia, including Colonial Life & Accident Insurance Company, the second-largest supplemental insurance company in the nation; the Ritedose Corporation, a pharmaceutical industry services company; AgFirst Farm Credit Bank, the largest bank headquartered in the state with over $30 billion in assets (the non-commercial bank is part of the Farm Credit System, the largest agricultural lending organization in the United States which was established by Congress in 1916); South State Bank, the largest commercial bank headquartered in South Carolina; Nexsen Pruet, LLC, a multi-specialty business law firm in the Carolinas; Spectrum Medical, an international medical software company; Wilbur Smith Associates, a full-service transportation and infrastructure consulting firm; and Nelson Mullins, a major national law firm. CSC's Financial Services Group, a major provider of software and outsourcing services to the insurance industry, is headquartered in the Columbia suburb of Blythewood.

Downtown revitalization

The city of Columbia has recently accomplished a number of urban redevelopment projects and has several more planned.[26] The historic Congaree Vista, a 1,200-acre (5 km2) district running from the central business district toward the Congaree River, features a number of historic buildings that have been rehabilitated since its revitalization begun in the late 1980s. Of note is the adaptive reuse of the Confederate Printing Plant on Gervais and Huger, used to print Confederate bills during the American Civil War. The city cooperated with Publix grocery stores to preserve the look. This won Columbia an award from the International Downtown Association.[27] The Vista district is also where the region's convention center and anchor Hilton hotel with a Ruth's Chris Steakhouse restaurant are located. Other notable developments under construction and recently completed include high-end condos and townhomes, hotels, and mixed-use structures.

The older buildings lining the Vista's main thoroughfare, Gervais Street, now house art galleries, restaurants, unique shops, and professional office space. Near the end of Gervais is the South Carolina State Museum and the EdVenture Children's Museum. Private student housing and some residential projects are going up nearby; the CanalSide development[28] at the site of the old Central Correctional Institution, is the most high-profile. At full build-out, the development will have 750 residential units and provides access to Columbia's waterfront. Lady Street between Huger and Assembly streets in the Vista and the Five Points neighborhood have undergone beautification projects, which mainly consisted of replacing curbs and gutters, and adding brick-paved sidewalks and angled parking.

Special revitalization efforts are being aimed at Main Street, which began seeing an exodus of department and specialty stores in the 1990s. The goal is to re-establish Main Street as a vibrant commercial and residential corridor, and the stretch of Main Street home to most businesses—-from Gervais to Blanding streets—-has been streetscaped in recent years. Notable developments completed in recent years along Main Street include an 18-story, $60 million tower at the high-profile corner of Main and Gervais streets, the renovation of the 1441 Main Street office building as the new Midlands headquarters for Wells Fargo Bank (formerly Wachovia Bank), a new sanctuary for the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church, the location of Mast General store in the historic Efird's building, and the relocation of the Nickelodeon theater. A façade improvement program for the downtown business district, implemented in 2011, has resulted in the restoration and improvement of the façades of several historic Main Street shopfronts. One of the most ambitious development projects in the city's history is currently underway which involves old state mental health campus downtown on Bull Street. Known formally as Columbia Common, this project will consist of rehabbing several historic buildings on the campus for residential, hospitality, and retail use.[29] A new minor league baseball stadium was recently built on the campus as well.[30]

Arts and culture

- Town Theatre is the country's oldest community theatre in continuous use. Located a block from the University of South Carolina campus, its playhouse is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Since 1917, the theatre has produced plays and musicals of wide general appeal.

- Trustus Theatre is Columbia's professional theatre company. Founded more than 20 years ago, Trustus brought a new dimension to theatre in South Carolina's capital city. Patrons have the opportunity to watch new shows directly from the stages of New York as well as classic shows rarely seen in Columbia.

- The Nickelodeon Theater is a 99-seat store front theater located on Main Street between Taylor and Blanding Streets. In operation since 1979, "the Nick", run by the Columbia Film Society, is home to two film screenings each evening and an additional matinée three days a week. The Nick is the only non-profit art house film theater in South Carolina and is the home for 25,000 filmgoers each year.

- Columbia Marionette Theatre has the distinction of being the only free standing theatre in the nation devoted entirely to marionette arts.

- The South Carolina Shakespeare Company performs the plays of Shakespeare and other classical works throughout the state.

- Workshop Theatre of South Carolina opened in 1967 as a place where area directors could practice their craft. The theatre produces musicals and Broadway fare and also brings new theatrical material to Columbia.

- The South Carolina State Museum is a comprehensive museum with exhibits in science, technology, history, and the arts. It is the state's largest museum and one of the largest museums in the Southeast.

- The Columbia Museum of Art features changing exhibits throughout the year. Located at the corner of Hampton and Main Streets, the museum offers art, lectures, films, and guided tours.

- EdVenture is one of the South's largest children's museums and the second largest in South Carolina. It is located next to the South Carolina State Museum on Gervais Street. The museum allows children to explore and learn while having fun.

- McKissick Museum is located on the University of South Carolina campus. The museum features changing exhibitions of art, science, regional history, and folk art.

- The Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum showcases an artifact collection from the Colonial period to the space age. The museum houses a diverse collection of artifacts from the South Carolina confederate period.

- The Richland County Public Library, named the 2001 National Library of the Year, serves area citizens through its main library and nine branches. The 242,000-square-foot (22,500 m2) main library has a large book collection, provides reference services, utilizes the latest technology, houses a children's collection, and displays artwork.

- The South Carolina State Library provides library services to all citizens of South Carolina through the interlibrary loan service utilized by the public libraries located in each county.

- The Columbia City Ballet is Columbia's ballet company, offering more than 80 major performances annually. Artistic director William Starrett, formerly of the Joffrey Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, runs the company.[31]

- The South Carolina Philharmonic Orchestra is Columbia's resident orchestra. The Philharmonic produces a full season of orchestral performances each year. Renowned musicians come to Columbia to perform as guest artists with the orchestra.[32] In April 2008 Morihiko Nakahara was named the new Music Director of the Philharmonic.

- The Columbia City Jazz Dance Company, formed in 1990 by artistic director Dale Lam, was named one of the "Top 50 Dance Companies in the USA" by Dance Spirit magazine. Columbia City Jazz specializes in modern, lyrical, and percussive jazz dance styles and has performed locally, regionally, and nationally in exhibitions, competitions, community functions, and international tours in Singapore, Plovdiv, Bulgaria, and Austria.[33]

- The Palmetto Opera debuted in 2003 with a performance of "Love, Murder & Revenge," a mixture of scenes from famous operas. The organization's mission is to present professional opera to the Midlands and South Carolina.[34]

- The Columbia Choral Society has been performing throughout the community since 1930. Under the direction of Dr. William Carswell, the group strives to stimulate and broaden interest in musical activities and to actively engage in the rehearsal and rendition of choral music.

- Alternacirque is a professional circus that produces variety shows and full-scale themed productions. Formed in 2007, Alternacirque is directed by Natalie Brown.[35][36]

- Pocket Productions is an arts organization devoted to inspiring and expanding the arts community in Columbia, SC, through ArtRageous,[37] Playing After Dark[38] and other community-based collaborative events.[39]

Movies filmed in the Columbia area include The Program, Renaissance Man, Chasers, Death Sentence, A Guy Named Joe, and Accidental Love/Nailed.

Venues

Colonial Life Arena

Colonial Life Arena, opened in 2002, is Columbia's premier arena and entertainment facility. Seating 18,000 for college basketball, it is the largest arena in the state of South Carolina and the tenth largest on-campus basketball facility in the nation, serving as the home of the men's and women's USC Gamecocks basketball teams. Located on the University of South Carolina campus, this facility features 41 suites, four entertainment suites, and the Frank McGuire Club, a full-service hospitality room with a capacity of 300. The facility has padded seating, a technologically advanced sound system, and a four-sided video scoreboard.[40]

Columbia Metropolitan Convention Center

The Columbia Metropolitan Convention, which opened in September 2004 as South Carolina's only downtown convention center,[41] is a 142,500-square-foot (13,240 m2), modern, state-of-the-art facility designed to host a variety of meetings and conventions. Located in the historic Congaree Vista district, this facility is close to restaurants, antique and specialty shops, art galleries, and various popular nightlife venues. The main exhibit hall contains almost 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2) of space; the Columbia Ballroom over 18,000 square feet (1,700 m2); and the five meeting rooms ranging in size from 1500 to 4,000 square feet (400 m2) add another 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2) of space. The facility is located next to the Colonial Life Arena.

Williams-Brice Stadium

Williams-Brice Stadium is the home of the USC Gamecocks' football team and is the 24th largest college football stadium in the nation.[42] It seats 80,250 people and is located just south of downtown Columbia. The stadium was built in 1934 with the help of federal Works Progress Administration funds, and initially seated 17,600. The original name was Carolina Stadium, but on September 9, 1972, it was renamed to honor the Williams and Brice families. Mrs. Martha Williams-Brice had left much of her estate to the university for stadium renovations and expansions. Her late husband, Thomas H. Brice, played football for the university from 1922 to 1924.

Koger Center for the Arts

Koger Center for the Arts provides Columbia with theatre, music, and dance performances that range from local acts to global acts.[43] The facility seats 2,256 persons. The center is named for philanthropists Ira and Nancy Koger, who made a substantial donation from personal and corporate funds for construction of the $15 million center. The first performance at the Koger Center was given by the London Philharmonic Orchestra and took place on Saturday, January 14, 1989. The facility is known for hosting diverse events, from the State of the State Address to the South Carolina Body Building Championship and the South Carolina Science Fair.

Carolina Coliseum

Carolina Coliseum, which opened in 1968, is a 12,401-seat facility which initially served as the home of the USC Gamecocks' basketball teams. The arena could be easily adapted to serve other entertainment purposes, including concerts, car shows, circuses, ice shows, and other popular events. The versatility and quality of the coliseum at one time allowed the university to use the facility for performing arts events such as the Boston Pops, Chicago Symphony, Feld Ballet, and other performances by important artists. An acoustical shell and a state-of-the-art lighting system assisted the coliseum in presenting such activities. The coliseum was the home of the Columbia Inferno, an ECHL team. However, since the construction of the Colonial Life Arena in 2002, the coliseum is no longer used for basketball, but is still used as classroom space for the Schools of Journalism and Hospitality, Retail, and Sport Management.

Township Auditorium

Township Auditorium seats 3,099 capacity and is located in downtown Columbia. The Georgian Revival building was designed by the Columbia architectural firm of Lafaye and Lafaye and constructed in 1930. The Township has hosted thousands of events from concerts to conventions to wrestling matches. The auditorium was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on September 28, 2005, and has recently undergone a $12 million extensive interior and exterior renovation.[44]

Charlie W. Johnson Stadium

The $13 million Charlie W. Johnson Stadium is the home of Benedict College football and soccer. The structure was completed and dedicated in 2006 and seats 11,000 with a maximum capacity of 16,000.

Founders Park

The Founders Park opened in February 2009. Seating 8,400 permanently for college baseball and an additional 1,000 for standing room only, it is the largest baseball stadium in the state of South Carolina and serves as the home of the University of South Carolina Gamecocks' baseball team. Located near Granby Park in close proximity to downtown Columbia, this facility features four entertainment suites, a picnic terrace down the left field line, and a dining deck that will hold approximately 120 fans. The state-of-the-art facility also features a technologically advanced sound system and a 47 feet (14 m) high × 44 feet (13 m) wide scoreboard.[45] The video portion is 16 feet (4.9 m) high × 28 feet (8.5 m) wide.

Spirit Communications Park

On January 6, 2015, developers broke ground on the $37 million Spirit Communications Park designed by architecture firm Populous. The stadium is the home for the Columbia Fireflies, a Minor League Baseball team playing in the South Atlantic League. It opened in April 2016 and can seat up to 7,501 people. Columbia had been without minor league baseball since the Capital City Bombers relocated to Greenville, South Carolina, in 2004.[46]

Sports

| Club | Sport | Years | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia Inferno[47][48][49][50] | Ice hockey | 2001–2008 | ECHL | |

| Columbia Fireflies | Baseball | 2016 | Minor League Baseball | Spirit Communications Park |

| Columbia Olde Grey | Rugby Union | 1967 | USA Rugby | Patton Stadium |

| Palmetto FC Bantams | Soccer | 2011 | USL PDL | Stone Stadium. The Bantams base of operations is in Greenwood, South Carolina, though the team plays several home games in Columbia. |

| Columbia QuadSquad | Roller Derby | 2007 | WFTDA | Jamil Temple |

In addition to sports programs at the University of South Carolina, Columbia has also hosted the women's U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials in 1996 and 2000[51] and the 2007 Junior Wildwater World Championships, which featured many European canoe and kayak racers.[52] The Colonial Life Arena has also hosted NBA exhibition games.[53]

Parks and recreation

The region's most popular park, Finlay Park has hosted just about everything from festivals and political rallies to road races and Easter Sunrise services. This 18-acre (73,000 m2) park has had two lives; first dedicated in 1859 as Sidney Park, named in honor of Algernon Sidney Johnson, a Columbia City Councilman, the park experienced an illustrious but short tenure. The park fell into disrepair after the Civil War and served as a site for commercial ventures until the late 20th century. In 1990, the park was reopened. It serves as the site for such events as Kids Day, The Summer Concert Series, plus many more activities. In 1992, the park was renamed Finlay Park, in honor of Kirkman Finlay, a past mayor of Columbia who had a vision to reenergize the historic Congaree Vista district, between Main Street and the river, and recreate the site that was formerly known as Sidney Park.

Memorial Park is a 4-acre (16,000 m2) tract of land in the Congaree Vista between Main Street and the river. The property is bordered by Hampton, Gadsden, Washington, and Wayne Streets and is one block south of Finlay Park. This park was created to serve as a memorial to those who served their country and presently has monuments honoring the USS Columbia warship and those that served with her during World War II, the China-Burma-India Theater Veterans of WWII, casualties of the Pearl Harbor attack of December 7, 1941, who were from South Carolina, Holocaust survivors who live in South Carolina as well as concentration camp liberators from South Carolina, and the State Vietnam War Veterans. The park was dedicated in November 1986 along with the unveiling of the South Carolina Vietnam Monument. In June 2000, the Korean War Memorial was dedicated at Memorial Park. In November 2014, Columbia native and resident of Boston, Henry Crede, gave a bronze statue and plaza in the park dedicated to his WWII comrades who served in the Navy from South Carolina.

Granby Park opened in November 1998 as a gateway to the rivers of Columbia, adding another access to the many river activities available to residents. Granby is part of the Three Rivers Greenway, a system of green spaces along the banks of the rivers in Columbia, adding another piece to the long-range plan and eventually connecting to the existing Riverfront Park. Granby is a 24-acre (97,000 m2) linear park with canoe access points, fishing spots, bridges, and ½ mile of nature trail along the banks of the Congaree River.

In the Five Points district of downtown Columbia is the park dedicated to the legacy and memory of the most celebrated civil rights leader in America, Martin Luther King Jr. Park. Formerly known as Valley Park, it was historically known to be largely restricted to Whites. Renaming the park after Martin Luther King Jr. in the late 1980s was seen as a progressive and unifying event on behalf of the city, civic groups, and local citizens. The park features a beautiful water sculpture and a community center. An integral element of the park is the Stone of Hope monument, unveiled in January 1996. Upon the monument is inscribed a portion of King's 1964 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech: "History is cluttered with the wreckage of nations and individuals that pursued that self-defeating path of hate. Love is the key to the solutions of the problems of the world."

One of Columbia's greatest assets is Riverbanks Zoo & Garden. Riverbanks Zoo is a sanctuary for more than 2,000 animals housed in natural habitat exhibits along the Saluda River. Just across the river, the 70-acre (280,000 m2) botanical garden is devoted to gardens, woodlands, plant collections, and historic ruins. Riverbanks has been named one of America's best zoos[54] and the No. 1 travel attraction in the Southeast.[55] It attracted over one million visitors in 2009.[56]

Situated along the meandering Congaree River in central South Carolina, Congaree National Park is home to champion trees, primeval forest landscapes, and diverse plant and animal life. This 22,200-acre (90 km2) park protects the largest contiguous tract of old-growth bottomland hardwood forest remaining in the United States. The park is an international biosphere reserve. Known for its giant hardwoods and towering pines, the park's floodplain forest includes one of the highest canopies in the world and some of the tallest trees in the eastern United States. Congaree National Park provides a sanctuary for plants and animals, a research site for scientists, and a place to walk and relax in a tranquil wilderness setting.

Sesquicentennial State Park is a 1,419-acre (6 km2) park, featuring a beautiful 30-acre (120,000 m2) lake surrounded by trails and picnic areas. The park's proximity to downtown Columbia and three major interstate highways attracts both local residents and travelers. Sesquicentennial is often the site of family reunions and group campouts. Interpretive nature programs are a major attraction to the park. The park also contains a two-story log house, dating back to the mid 18th century, which was relocated to the park in 1969. This house is believed to be the oldest building still standing in Richland County. The park was originally built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. Evidence of their craftsmanship is still present today.

In November 1996, the River Alliance proposed that a 12-mile (19 km) linear park system be created to link people to their rivers. This was named the Three Rivers Greenway, and the $18 million estimated cost was agreed to by member governments (the cities of Cayce, Columbia, and West Columbia) with the proviso that the Alliance recommend an acceptable funding strategy.

While the funding process was underway, an existing city of Columbia site located on the Congaree River offered an opportunity to be a pilot project for the Three Rivers Greenway. The Alliance was asked to design and permit for construction by a general contractor this component. This approximately one-half-mile segment of the system was opened in November 1998. It is complete with 8-foot (2.4 m) wide concrete pathways, vandal-proof lighting, trash receptacles, water fountains, picnic benches, overlooks, bank fishing access, canoe/kayak access, a public restroom and parking. These set the standards for the common elements in the rest of the system. Eventually, pathways will run from Granby to the Riverbanks Zoo. Boaters, sportspeople, and fisherpeople will have access to the area, and additional recreational uses are being planned along the miles of riverfront.

Running beside the historic Columbia Canal, Riverfront Park hosts a two and a half-mile trail. Spanning the canal is an old railway bridge that now is a pedestrian walkway. The park is popular for walking, running, bicycling, and fishing. Picnic tables and benches dot the walking trail. Markers are located along the trail so that visitors can measure distance. The park is part of the Palmetto Trail, a hiking and biking trail that stretches the entire length of the state, from Greenville to Charleston.

Other parks in the Columbia area include:

- W. Gordon Belser Arboretum

- Maxcy Gregg Park

- Hyatt Park

- Earlewood Park

- Granby Park

- Owens Field Park

- Guignard Park

- Southeast Park

- Harbison State Forest

Government

The city of Columbia has a council-manager form of government. The mayor and city council are elected every four years, with no term limits. Elections are held in the spring of even numbered years. Unlike other mayors in council-manager systems, the Columbia mayor has the power to veto ordinances passed by the council; vetoes can be overridden by a two-thirds majority of the council, which appoints a city manager to serve as chief administrative officer. The current mayor is Democrat Stephen K. Benjamin, who succeeded longtime mayor and fellow Democrat Bob Coble in 2010. Teresa Wilson is the current city manager.

The city council consists of six members, four from districts and two elected at-large. The city council is responsible for making policies and enacting laws, rules, and regulations in order to provide for future community and economic growth, in addition to providing the necessary support for the orderly and efficient operation of city services.

At-Large

- Tameika Isaac Devine

- Cameron A. Runyan

Districts

- 1: Sam Davis

- 2: Brian DeQuincey Newman

- 3: Moe Baddourah

- 4: Leona Plaugh

See related article Past mayors of Columbia, South Carolina

The city's police force is the Columbia Police Department. The chief of police answers to the city manager. Presently, the chief of police is W.H. "Skip" Holbrook; Holbrook was sworn in on April 11, 2014.[57]

The South Carolina Department of Corrections, headquartered in Columbia,[58] operates several correctional facilities in Columbia. They include the Broad River Correctional Institution,[59] the Goodman Correctional Institution,[60] the Camille Griffin Graham Correctional Institution,[61] the Stevenson Correctional Institution,[62] and the Campbell Pre-Release Center.[63] Graham houses the state's female death row.[64] The state of South Carolina's execution chamber is located at Broad River. From 1990 to 1997, Broad River housed the state's male death row.[65]

Military installations

- Fort Jackson is the U.S. Army's largest training post.

- McEntire Joint National Guard Station is under command of the South Carolina Air National Guard.

Education

Colleges and universities

Columbia is home to the main campus of the University of South Carolina, which was chartered in 1801 as South Carolina College and in 1906 as the University of South Carolina.[66] The university has 350 degree programs and enrolls 31,964 students throughout fifteen degree-granting colleges and schools.[67] It is an urban university, located in downtown Columbia.

Columbia is also home to:

- Allen University – Allen University was founded in 1870 by the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Allen University is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) to award baccalaureate degrees.[68]

- Benedict College – Founded in 1870, Benedict is an independent coeducational college. Benedict is one of the fastest growing of the 39 United Negro College Fund schools. In addition to an increase in enrollment, Benedict has also seen an increase in average SAT scores, Honors College enrollee rates, capital giving dollars, and the number of research grants awarded. Recently, Benedict has been subject to a series of recent controversies, including basing up to 60 percent of grades solely on effort,[69] which have nearly resulted in its losing its accreditation. However, in recent months the college has improved its financial standing and is seeking to boost its enrollment.

- Columbia College – Founded in 1854, Columbia College is a private, four-year, liberal arts college for women with a coeducational Evening College and Graduate School. The college has been ranked since 1994 by U.S. News & World Report as one of the top ten regional liberal arts colleges in the South.

- Columbia International University is a biblically based, private Christian institution committed to "preparing men and women to know Christ and to make Him known."

- ECPI University has specialized in student-centered technology, business, criminal justice, and health science for 47 years – A leading private university offering master's, bachelor's, associate degree and diploma programs. Continuing Education certification programs are also available. ECPI University is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools to award associate, baccalaureate, and master's degrees and diploma programs. ECPI University Columbia campus also has programmatic accreditation for Medical Assisting with the Accrediting Bureau of Health Education Schools.

- Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary – This institution, founded in 1830, is a seminary of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. One of the oldest Lutheran seminaries in North America, Southern is a fully accredited graduate school of theology preparing women and men for the ordained and lay ministries of the church. The wooded 17-acre (69,000 m2) campus is situated atop Seminary Ridge in Columbia, the highest point in the Midlands area, near the geographic center of the city.

- Midlands Technical College – Midlands Tech is part of the South Carolina Technical College System. It is a two-year, comprehensive, public, community college, offering a wide variety of programs in career education, four-year college-transfer options, and continuing education. Small classes, individualized instruction, and student support services are provided. Most of the college's teaching faculty holds master's or doctoral degrees.

- Fortis College[70] – Fortis College is part of the Educational Affiliates Inc, and offers many different career-based degrees.

- South Carolina School of Leadership – Established in 2006, South Carolina School of Leadership (SCSL) is a post-secondary "gap year" school with an intense focus on Christian discipleship and leadership development.[71] SCSL uses curriculum from Valley Forge Christian College.

- Virginia College[72] – Virginia College received senior college recognition from the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools (ACICS) which now accredits all programs at the school's campuses

Columbia is also the site of several extension campuses, including those for Erskine Theological Seminary, South University, and the University of Phoenix.

Private schools

- Ben Lippen School

- Bethel Learning Centers

- Cardinal Newman

- Central Carolina Christian Academy

- Columbia Jewish Day School

- Colonial Christian Academy

- Covenant Classical Christian School

- Glenforest School

- Grace Christian School

- Hammond School

- Harmony School

- Heathwood Hall

- Heritage Christian Academy

- Islamic Academy of Columbia

- Montessori School of Columbia

- Northside Christian Academy

- Palmetto Baptist Academy

- Sandhills School

- Saint John Neumann Catholic School

- Saint Joseph Catholic School

- Saint Martin de Porres Catholic School

- Saint Peter's Catholic School

- Timmerman School

- V.V. Reid Elementary

Public school districts

|

Media

Columbia's daily newspapers include The State[73] and Cola Daily,[74] and its alternative newspapers include Free Times,[75] The Columbia Star,[76] Carolina Panorama Newspaper,[77] and SC Black News.[78]

Columbia Metropolitan Magazine[79] is a bi-monthly publication about news and events in the metropolitan area. Greater Columbia Business Monthly[80] highlights economic development, business, education, and the arts. Q-Notes,[81] a bi-weekly newspaper serving the LGBT community and published in Charlotte, is distributed to locations in Columbia and via home delivery.

Columbia is home to the headquarters and production facilities of South Carolina Educational Television and ETV Radio, the state's public television and public radio networks.[82]

Columbia has the 78th largest television market in the United States.[83] Network affiliates include WIS (NBC), WLTX (CBS), WACH (FOX) and WOLO (ABC).

Infrastructure

Transportation

Mass transit

The Comet, officially the Central Midlands Regional Transit Authority, is the agency responsible for operating mass transit in the greater Columbia area including Cayce, West Columbia, Forest Acres, Arcadia Lakes, Springdale, Lexington [84] and the St. Andrews area. COMET operates express shuttles, as well as bus service serving Columbia and its immediate suburbs. The authority was established in October 2002 after SCANA released ownership of public transportation back to the city of Columbia. Since 2003, COMET has provided transportation for more than 2 million passengers, has expanded route services, and introduced 43 new ADA accessible buses offering a safer, more comfortable means of transportation. CMRTA has also added 10 natural gas powered buses to the fleet. COMET went under a name change and rebranding project in 2013. Before then, the system was called the Columbia Metropolitan Rapid Transit Association or "CMRTA".[85]

The Central Midlands Council of Governments is in the process of investigating the potential for rail transit in the region. Routes into downtown Columbia originating from Camden, Newberry, and Batesburg-Leesville are in consideration, as is a potential line between Columbia and Charlotte connecting the two mainlines of the future Southeastern High Speed Rail Corridor.[86][87][88][89]

Roads and highways

Columbia's central location between the population centers of South Carolina has made it a transportation focal point with three interstate highways and one interstate spur.

Interstates

.svg.png) I-26 Interstate 26 travels from northwest to southeast and connects Columbia to the other two major population centers of South Carolina: the Greenville-Spartanburg area in the northwestern part of the state and North Charleston – Charleston area in the southeastern part of the state. It also serves the nearby towns and suburbs of Chapin, Irmo, Harbison, Gaston, and Swansea.

I-26 Interstate 26 travels from northwest to southeast and connects Columbia to the other two major population centers of South Carolina: the Greenville-Spartanburg area in the northwestern part of the state and North Charleston – Charleston area in the southeastern part of the state. It also serves the nearby towns and suburbs of Chapin, Irmo, Harbison, Gaston, and Swansea..svg.png) I-20 Interstate 20 travels from west to east and connects Columbia to Atlanta and Augusta in the west and Florence in the east. It serves the nearby towns and suburbs of Pelion, Lexington, West Columbia, Sandhill, Pontiac, and Elgin. Interstate 20 is also used by travelers heading to Myrtle Beach, although the interstate's eastern terminus is in Florence.

I-20 Interstate 20 travels from west to east and connects Columbia to Atlanta and Augusta in the west and Florence in the east. It serves the nearby towns and suburbs of Pelion, Lexington, West Columbia, Sandhill, Pontiac, and Elgin. Interstate 20 is also used by travelers heading to Myrtle Beach, although the interstate's eastern terminus is in Florence..svg.png) I-77 Interstate 77 begins at a junction with Interstate 26 south of Columbia and travels north to Rock Hill and Charlotte. This interstate also provides direct access to Fort Jackson, the U.S. Army's largest training base and one of Columbia's largest employers. It serves the nearby towns and suburbs of Forest Acres, Gadsden, and Blythewood.

I-77 Interstate 77 begins at a junction with Interstate 26 south of Columbia and travels north to Rock Hill and Charlotte. This interstate also provides direct access to Fort Jackson, the U.S. Army's largest training base and one of Columbia's largest employers. It serves the nearby towns and suburbs of Forest Acres, Gadsden, and Blythewood..svg.png) I-126 Interstate 126 begins downtown at Elmwood Avenue and travels west towards Interstate 26 and Interstate 20. It provides access to Riverbanks Zoo.

I-126 Interstate 126 begins downtown at Elmwood Avenue and travels west towards Interstate 26 and Interstate 20. It provides access to Riverbanks Zoo.

US routes

State highways

Air

The city and its surroundings are served by Columbia Metropolitan Airport (IATA: CAE, ICAO: KCAE, FAA LID: CAE). The airport itself is serviced by American Eagle, Delta, and United Express airlines. In addition, the city is also served by the much smaller Jim Hamilton–L.B. Owens Airport (IATA: CUB, ICAO: KCUB, FAA LID: CUB) located in the Rosewood neighborhood. It serves as the county airport for Richland County and offers general aviation.

Intercity rail

The city is served daily by Amtrak station, with the Silver Star trains connecting Columbia with New York City, Washington, DC, Savannah, Jacksonville, Orlando, Tampa, and Miami. The station is located at 850 Pulaski St.

Intercity bus

Greyhound Lines formerly operated a station on Gervais Street, in the eastern part of downtown, providing Columbia with intercity bus transportation. The station relocated to 710 Buckner Road in February 2015.[90]

MegaBus began operations in Columbia in 2015. There routes include stops in Fayetteville, North Carolina, Washington, DC, and New York City, New York. The station is located on Sumter Street.

Health care

The Sisters of Charity Providence Hospitals is sponsored by the Sisters of Charity of Saint Augustine (CSA) Health System. The non-profit organization is licensed for 304 beds and comprises four entities: Providence Hospital, Providence Heart Institute, Providence Hospital Northeast, and Providence Orthopaedic & NeuroSpine Institute. Providence Hospital, located in downtown Columbia, was founded by the Sisters of Charity of Saint Augustine in 1938. The facility offers cardiac care through Providence Heart Institute, which is considered a quality cardiac center in South Carolina. Providence Hospital Northeast is a 46-bed community hospital established in 1999 that offers a range of medical services in surgery, emergency care, women's and children's services, and rehabilitation. Providence Northeast is home to Providence Orthopaedic & NeuroSpine Institute, which provides medical and surgical treatment of diseases and injuries of the bones, joints, and spine.

Palmetto Health is a South Carolina nonprofit public benefit corporation consisting of Palmetto Health Richland and Palmetto Health Baptist hospitals (2locations; 1 downtown and 1 in the Harbison area) in Columbia. Palmetto Health provides health care for nearly 70 percent of the residents of Richland County and almost 55 percent of the health care for both Richland and Lexington counties. Palmetto Health Richland is the primary teaching hospital for the University of South Carolina School of Medicine. Palmetto Health Baptist recently underwent a $40 million multi-phase modernization which included 37,000 square feet (3,400 m2) of new construction and 81,000 square feet (7,500 m2) of renovations. The extensive health system also operates Palmetto Health Children's Hospital and Palmetto Health Heart Hospital, the state's first freestanding hospital dedicated solely to heart care, which opened in January 2006. The Palmetto Health South Carolina Cancer Center offers patient services at the Palmetto Health Baptist and Palmetto Health Richland campuses; both are recognized by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer as a Network Cancer Program.

Lexington Medical Center is a network of hospitals—urgent care centers that are all located throughout Lexington County, South Carolina. There are currently six urgent care centers located in Lexington, Irmo, Batesburg-Leesville, Swansea, and Gilbert. The main hospital is in West Columbia. LMC opened in 1971 but quickly grew into a large center that has been growing every year since its opening. Currently, the main center offers an array of services from emergency treatments to the upcoming heart center.

The Wm. Jennings Bryan Dorn VA Medical Center is a 216-bed facility, encompassing acute medical, surgical, psychiatric, and long-term care. The hospital provides primary, secondary, and some tertiary care.[91] An affiliation is held with the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, located on the hospital grounds. A sharing agreement is in place with Moncrief Army Community Hospital at Fort Jackson and the 20th Medical Group at Shaw AFB in Sumter.

Notable people

- Clarissa Minnie Thompson Allen, writer & educator[92]

- Aziz Ansari, Golden Globe nominated actor. Was in Parks and Recreation.

- Charles W. Bagnal, United States military officer and lawyer

- Band of Horses, alternative rock band

- Samuel Beam, musician

- Zinn Beck, MLB player, manager

- Paul Benjamin, actor

- Joseph Bernardin, Catholic cardinal

- Ryan Bethea, football player

- Blue Sky, artist

- Charles F. Bolden, Jr., astronaut

- Bored Suburban Youth, hardcore punk band

- Michael Boulware, NFL safety

- Peter Boulware, NFL linebacker

- Bob Bowman, swim coach

- Phillip Bush, pianist

- Preston Callison, lawyer and politician

- Mark Cerney, founder of the Next of Kin Registry (NOKR)

- Bruce Chen, Major League Baseball

- Kelsey Chow, actress

- Mike Colter, actor

- Angell Conwell, actress

- Tyrone Corbin, NBA player and coach

- Crossfade, alternative metal/hard rock band

- Danny!, musician

- Arthur C. Davis, United States Navy admiral

- Kristin Davis, actress

- James Dickey, poet. author

- Stanley Donen, film director and choreographer

- Brad Edwards, NFL player

- Alex English, NBA forward

- The Fabulous Moolah, WWE/WWF wrestler

- Sarah Mae Flemming, civil rights activist

- Michael Flessas, actor

- William Price Fox, novelist

- Samkon Gado, NFL player

- Ed Grady, actor[93]

- Maxcy Gregg, Civil War veteran

- Alexander Cheves Haskell, Civil War veteran

- Kirby Higbe, MLB player

- Robert H. Hodges, Jr., federal judge

- Scott Holroyd, actor

- Hootie & the Blowfish, band

- Danielle Howle, musician and songwriter

- LaMarr Hoyt, MLB Player

- Rob Huebel, actor

- Fiona Hutchison, actress

- Alexis Jordan, singer

- Dustin Johnson, golfer

- Lloyd E. Jones, United States Army, major general[94]

- Alicia Leeke, artist

- Guy Lipscomb, artist

- Xavier McDaniel, NBA player

- Brooklyn Mack, ballet dancer[95]

- Ed Madden, poet, professor, and editor

- B.J. McKie, basketball player

- Ray McManus, poet[96]

- Craig Melvin news anchor

- The Movement, reggae band

- Kary Mullis, scientist (Nobel Prize winner/graduate of Dreher High School)

- Allison Munn, actress

- Jermaine O'Neal, National Basketball Association player

- Steve Pettit, fifth president of Bob Jones University

- Tom Poland, author

- Chris Potter, musician

- Zach Prince, USL Second Division

- Lil Ru, singer

- Gloria Saunders actress

- Richard Seymour, National Football League

- Steve Spurrier, college football coach

- Duce Staley, NFL player

- Josh Stolberg, screenwriter

- Angie Stone, singer

- Freddie Summers, American football player

- Robin Swicord, screenwriter

- Stretch Arm Strong, hardcore punk band

- Toro Y Moi, musician and songwriter

- Tom Turnipseed, activist, former member of the South Carolina State Senate

- Ashley Tuttle, ballet dancer

- Washed Out, musician and songwriter

- Ron Westray, trombonist

- Del Wilkes, pro wrestler

- Bill Workman, economic development consultant and former mayor of Greenville, South Carolina; former Columbia resident

- W. D. Workman, Jr., newspaper editor

- Lee Thompson Young, actor

- John H. Yardley, pathologist

- Young Jeezy, rapper, born in Columbia

Accolades

Columbia has been the recipient of several awards and achievements in various sectors of note. In October 2009, Columbia was listed in U.S. News & World Report as one of the best places to retire citing location and median housing price as key contributors.[97] As of July 2013 Columbia was named one of "10 Great Cities to Live In" by nationally prominent Kiplinger Magazine, a personal finance publication. Most recently, the city has been named a top mid-sized market in the nation for relocating families [98] as well as one of 30 communities named "America's Most Livable Communities," an award given by the Washington -based non-profit Partners for Livable Communities that honors communities that are developing themselves in the creative economy.

Sister cities

The city of Columbia has five sister cities:[99]

Kaiserslautern, Germany

Kaiserslautern, Germany Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Cluj-Napoca, Romania Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Plovdiv, Bulgaria Chelyabinsk, Russia

Chelyabinsk, Russia Accra, Ghana

Accra, Ghana

See also

- Columbia High School (Columbia, South Carolina)

- Columbia, Newberry and Laurens Railroad, historic railroad

- Columbia Record, former afternoon daily newspaper

- Columbia Speedway

- Columbia South Carolina Temple, an operating temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Columbia Theological Seminary, formerly in Columbia, South Carolina, now in Decatur, Georgia

- George Stinney, youngest person to be executed in the United States

Notes

- ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ↑ Official records for Columbia were kept at downtown from June 1887 to December 1947, and at Columbia Airport since January 1948. For more information, see Threadex

References

- 1 2 "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Columbia city, South Carolina". Census Bureau. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ↑ Swanton, John R. (1952), The Indian Tribes of North America, Smithsonian Institution, p. 93, ISBN 0-8063-1730-2, OCLC 52230544

- ↑ Charles Hudson (September 1998). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South's Ancient Chiefdoms. University of Georgia Press. pp. 234–238. ISBN 978-0-8203-2062-5. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Columbia." City of Columbia Official Web Site. www.columbiasc.net. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Urban Slavery in Columbia". Slavery at South Carolina College, 1801-1865:

The Foundations of the University of South Carolina. Retrieved September 14, 2014. - ↑ Sherman, William Tecumse (2009). Burning of Columbia, South Carolina. Great Neck Publishing. p. 384.

- ↑ "Washington Street Methodist Church - Our History". Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Mission". Columbia Music Festival Association. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Columbia Metropolitan Airport – Columbia, SC – Columbia's airport". Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ↑ South Columbia Development Corporation

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ Archived February 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Official Series Description - ORANGEBURG Series. Soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov. Retrieved on July 24, 2013.

- ↑ Official Series Description - NORFOLK Series. Soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov. Retrieved on July 24, 2013.

- ↑ Official Series Description - MARLBORO Series. Soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov. Retrieved on July 24, 2013.