Groundwater pollution

.jpg)

Groundwater pollution (also called groundwater contamination) occurs when pollutants are released to the ground and make their way down into groundwater. It can also occur naturally due to the presence of a minor and unwanted constituent, contaminant or impurity in the groundwater, in which case it is more likely referred to as contamination rather than pollution.

The pollutant creates a contaminant plume within an aquifer. Movement of water and dispersion within the aquifer spreads the pollutant over a wider area. Its advancing boundary, often called a plume edge, can intersect with groundwater wells or daylight into surface water such as seeps and spring, making the water supplies unsafe for humans and wildlife. The movement of the plume, called a plume front, may be analyzed through a hydrological transport model or groundwater model. Analysis of groundwater pollution may focus on soil characteristics and site geology, hydrogeology, hydrology, and the nature of the contaminants.

Pollution can occur from on-site sanitation systems, landfills, effluent from wastewater treatment plants, leaking sewers, petrol stations or from over application of fertilizers in agriculture. Pollution (or contamination) can also occur from naturally occurring contaminants, such as arsenic or fluoride. Using polluted groundwater causes hazards to public health through poisoning or the spread of disease.

Different mechanisms have influence on the transport of pollutants, e.g. diffusion, adsorption, precipitation, decay, in the groundwater. The interaction of groundwater contamination with surface waters is analyzed by use of hydrology transport models.

Pollutant types

Contaminants found in groundwater cover a broad range of physical, inorganic chemical, organic chemical, bacteriological, and radioactive parameters. Principally, many of the same pollutants that play a role in surface water pollution may also be found in polluted groundwater, although their respective importance may differ.

Pathogens

Pathogens contained in feces can lead to groundwater pollution when they are given the opportunity to reach the groundwater, making it unsafe for drinking. Of the four pathogen types that are present in feces (bacteria, viruses, protozoa and helminths or helminth eggs), the first three can be commonly found in polluted groundwater, whereas the relatively large helminth eggs are usually filtered out by the soil matrix.

Groundwater that is contaminated with pathogens can lead to fatal fecal-oral transmission of diseases (e.g. cholera, diarrhoea).[1][2]

If the local hydrogeological conditions (which can vary within a space of a few square kilometres) are ignored, pit latrines can cause significant public health risks via contaminated groundwater.

Nitrate

In addition to the issue of pathogens, there is also the issue of nitrate pollution in groundwater from pit latrines, which has led to numerous cases of "blue baby syndrome" in children, notably in rural countries such as Romania and Bulgaria.[3] Nitrate levels above 10 mg/L (10 ppm) in groundwater can cause "blue baby syndrome" (acquired methemoglobinemia).[4]

Nitrate can also enter the groundwater via excessive use of fertilizers, including manure. This is because only a fraction of the nitrogen-based fertilizers is converted to produce and other plant matter. The remainder accumulates in the soil or lost as run-off.[5] High application rates of nitrogen-containing fertilizers combined with the high water-solubility of nitrate leads to increased runoff into surface water as well as leaching into groundwater, thereby causing groundwater pollution.[6][7][8] The excessive use of nitrogen-containing fertilizers (be they synthetic or natural) is particularly damaging, as much of the nitrogen that is not taken up by plants is transformed into nitrate which is easily leached.[9]

The nutrients, especially nitrates, in fertilizers can cause problems for natural habitats and for human health if they are washed off soil into watercourses or leached through soil into groundwater.

Volatile organic compounds

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are a dangerous contaminant of groundwater. They are generally introduced to the environment through careless industrial practices. Many of these compounds were not known to be harmful until the late 1960s and it was some time before regular testing of groundwater identified these substances in drinking water sources.

Others

Organic pollutants can also be found in groundwater, such as insecticides and herbicides, a range of organohalides and other chemical compounds, petroleum hydrocarbons, various chemical compounds found in personal hygiene and cosmetic products, drug pollution involving pharmaceutical drugs and their metabolites. Inorganic pollutans might include ammonia, nitrate, phosphate, heavy metals or radionuclides.

Naturally occurring

Arsenic

In the Ganges Plain of northern India and Bangladesh severe contamination of groundwater by naturally occurring arsenic affects 25% of water wells in the shallower of two regional aquifers. The pollution occurs because aquifer sediments contain organic matter that generates anaerobic conditions in the aquifer. These conditions result in the microbial dissolution of iron oxides in the sediment and, thus, the release of the arsenic, normally strongly bound to iron oxides, into the water. As a consequence, arsenic-rich groundwater is often iron-rich, although secondary processes often obscure the association of dissolved arsenic and dissolved iron.

Fluoride

In areas that have naturally occurring high levels of fluoride in groundwater which is used for drinking water, both dental and skeletal fluorosis can be prevalent and severe.[10]

Causes

Landfill leachate

Leachate from sanitary landfills can lead to groundwater pollution.

Love Canal was one of the most widely known examples of groundwater pollution. In 1978, residents of the Love Canal neighborhood in upstate New York noticed high rates of cancer and an alarming number of birth defects. This was eventually traced to organic solvents and dioxins from an industrial landfill that the neighborhood had been built over and around, which had then infiltrated into the water supply and evaporated in basements to further contaminate the air. Eight hundred families were reimbursed for their homes and moved, after extensive legal battles and media coverage.

On-site sanitation systems

.jpg)

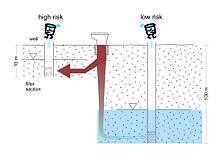

Groundwater pollution with pathogens and nitrate can also occur from the liquids infiltrating into the ground from on-site sanitation systems such as pit latrines and septic tanks, depending on the population density and the hydrogeological conditions.[1]

Liquids leach from the pit and pass the unsaturated soil zone (which is not completely filled with water). Subsequently, these liquids from the pit enter the groundwater where they may lead to groundwater pollution. This is a problem if a nearby water well is used to supply groundwater for drinking water purposes. During the passage in the soil, pathogens can die off or be adsorbed significantly, mostly depending on the travel time between the pit and the well.[11] Most, but not all pathogens die within 50 days of travel through the subsurface.[12]

The degree of pathogen removal strongly varies with soil type, aquifer type, distance and other environmental factors.[13] For this reason, it is difficult to estimate the safe distance between a pit latrine or a septic tank and a water source. In any case, such recommendations about the safe distance are mostly ignored by those building pit latrines. In addition, household plots are of a limited size and therefore pit latrines are often built much closer to groundwater wells than what can be regarded as safe. This results in groundwater pollution and household members falling sick when using this groundwater as a source of drinking water.

Sewage treatment plants

The treated effluent from sewage treatment plants may also reach the aquifer if the effluent is infiltrated or discharged to local surface water bodies. Therefore, those substances that are not removed in conventional sewage treatment plants may reach the groundwater as well.[14]

For example, detected concentrations of pharmaceutical residues in groundwater were in the order of 50 ng/L in several locations in Germany.[15] This is because in conventional sewage treatment plants, micro-pollutants such as hormones, pharmaceutical residues and other micro-pollutants contained in urine and feces are only partially removed and the remainder is discharged into surface water, from where it may also reach the groundwater.

Hydraulic Fracturing

The recent growth of Hydraulic Fracturing ("Fracking") wells in the United States has raised valid concerns regarding its potential risks of contaminating groundwater resources. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), along with many other researchers, has been delegated to study the relationship between hydraulic fracturing and drinking water resources. While the EPA has not found significant evidence of a widespread, systematic impact on drinking water by hydraulic fracturing, this may be due to insufficient systematic pre- and post- hydraulic fracturing data on drinking water quality, and the presence of other agents of contamination that preclude the link between shale oil/gas extraction and its impact.[16]

Despite the EPA's lack of profound widespread evidence, other researchers have made significant observations of rising groundwater contamination in close proximity to major shale oil/gas drilling sites located in Marcellus[17] (Northeastern Pennsylvania) and Horn River Basins[18] (British Columbia, Canada). Within one kilometer of these specific sites, a subset of shallow drinking water consistently showed higher concentration levels of methane, ethane, and propane concentrations than normal. An evaluation of higher Helium and other noble gas concentration along with the rise of hydrocarbon levels supports the distinction between hydraulic fracturing fugitive gas and naturally occurring "background" hydrocarbon content. This contamination is speculated to be the result of leaky, failing, or improperly installed gas well casings.[19] Furthermore, it is theorized that contamination could also result from the capillary migration of deep residual hyper-saline water and hydraulic fracturing fluid, slowly flowing through faults and fractures until finally making contact with groundwater resources;[19] however, many researchers argue that the permeability of rocks overlying shale formations are too low to allow this to ever happen sufficiently.[20] To ultimately prove this theory, there would have to be traces of toxic trihalomethanes (THM) since they are often associated with the presence of stray gas contamination, and typically co-occur with high halogen concentrations in hyper-saline waters.[20]

While conclusions regarding groundwater pollution as the result to hydraulic fracturing fluid flow is restricted in both space and time, researchers have hypothesized that the potential for systematic stray gas contamination depends mainly on the integrity of the shale oil/gas well structure, along with its relative geological location to local fracture systems that could potentially provide flow paths for fugitive gas migration.[19][20]

Though widespread, systematic contamination by hydraulic fracturing has been heavily disputed, one major source of contamination that has the most consensus among researchers of being the most problematic is site-specific accidental spillage of hydraulic fracturing fluid and produced water. So far, a significant majority of groundwater contamination events are derived from surface-level anthropogenic routes rather than the subsurface flow from underlying shale formations.[21] Examples of such events include: a fracking fluid spillage in Acorn Fork Creek, Kentucky that caused a widespread death among aquatic species in 2007;[22] a 420,000 gallon spillage of hyper-saline produced water that turned a once very-fertile farmland in New Mexico into a dead-zone in 2010;[23] and a 42,000 gallon fracking fluid spillage in Arlington, Texas that necessitated an evacuation of over a 100 homes in 2015.[24] While the damage can be obvious, and much more effort is being done to prevent these accidents from occurring so frequently, the lack of data from fracking oil spills continue to leave researchers in the dark. In many of these events, the data acquired from the leakage or spillage is often very vague, and thus would lead researchers to lacking conclusions.[25]

Other

Further causes of groundwater pollution are excessive application of fertilizer or pesticides, chemical spills from commercial or industrial operations, chemical spills occurring during transport (e.g. spillage of diesel fuels), illegal waste dumping, infiltration from urban runoff or mining operations, road salts, de-icing chemicals from airports and even atmospheric contaminants since groundwater is part of the hydrologic cycle.[26] Over application of animal manure may also result in groundwater pollution with pharmaceutical residues.

Groundwater pollution can also occur from leaking sewers which has been observed for example in Germany.[27]

Mechanisms

The passage of water through the subsurface can provide a reliable natural barrier to contamination but it only works under favorable conditions.[1]

The stratigraphy of the area plays an important role in the transport of pollutants. An area can have layers of sandy soil, fractured bedrock, clay, or hardpan. Areas of karst topography on limestone bedrock are sometimes vulnerable to surface pollution from groundwater. Earthquake faults can also be entry routes for downward contaminant entry. Water table conditions are of great importance for drinking water supplies, agricultural irrigation, waste disposal (including nuclear waste), wildlife habitat, and other ecological issues.[28]

Interactions with surface water

Although interrelated, surface water and groundwater have often been studied and managed as separate resources.[29] Surface water seeps through the soil and becomes groundwater. Conversely, groundwater can also feed surface water sources. Sources of surface water pollution are generally grouped into two categories based on their origin.

Interactions between groundwater and surface water are complex. Consequently, groundwater pollution, sometimes referred to as groundwater contamination, is not as easily classified as surface water pollution.[29] By its very nature, groundwater aquifers are susceptible to contamination from sources that may not directly affect surface water bodies, and the distinction of point vs. non-point source may be irrelevant. A spill or ongoing release of chemical or radionuclide contaminants into soil (located away from a surface water body) may not create point or non-point source pollution but can contaminate the aquifer below, creating a toxic plume.

Prevention

Locating on-site sanitation systems

On-site sanitation systems can be designed in such a way that groundwater pollution from these sanitation systems is prevented from occurring.[1][30] Detailed guidelines have been developed to estimate safe distances to protect groundwater sources from pollution from on-site sanitation.[31][32] The following criteria have been proposed for safe siting (i.e. deciding on the location) of on-site sanitation systems:[1]

- Horizontal distance between the drinking water source and the sanitation system

- Guideline values for horizontal separation distances between on-site sanitation systems and water sources vary widely (e.g. 15 to 100 m horizontal distance between pit latrine and groundwater wells)[13]

- Vertical distance between drinking water well and sanitation system

- Aquifer type

- Groundwater flow direction

- Impermeable layers

- Slope and surface drainage

- Volume of leaking wastewater

- Superposition, i.e. the need to consider a larger planning area

As a very general guideline it is recommended that the bottom of the pit should be at least 2 m above groundwater level, and a minimum horizontal distance of 30 m between a pit and a water source is normally recommended to limit exposure to microbial contamination.[1] However, no general statement should be made regarding the minimum lateral separation distances required to prevent contamination of a well from a pit latrine.[1] For example, even 50 m lateral separation distance might not be sufficient in a strongly karstified system with a downgradient supply well or spring, while 10 m lateral separation distance is completely sufficient if there is a well developed clay cover layer and the annular space of the groundwater well is well sealed.

Legislation

United States

In November 2006, the Environmental Protection Agency published the Ground Water Rule in the United States Federal Register. The EPA was worried that the ground water system would be vulnerable to contamination from fecal matter. The point of the rule was to keep microbial pathogens out of public water sources.[33] The 2006 Ground Water Rule was an amendment of the 1996 Safe Drinking Water Act.

The ways to deal with groundwater pollution that has already occurred can be grouped into the following categories: containing the pollutants to prevent them from migrating further; removing the pollutants from the aquifer; remediating the aquifer by either immobilizing or detoxifying the contaminants while they are still in the aquifer (in-situ); treating the groundwater at its point of use; or abandoning the use of this aquifer's groundwater and finding an alternative source of water.[34]

Management

Point-of-use treatment

Portable water purification devices or "point-of-use" (POU) water treatment systems and field water disinfection techniques can be used to remove some forms of groundwater pollution prior to drinking, namely any fecal pollution. Many commercial portable water purification systems or chemical additives are available which can remove pathogens, chlorine, bad taste, odors, and heavy metals like lead and mercury.

Techniques include boiling, filtration, activated charcoal absorption, chemical disinfection, ultraviolet purification, ozone water disinfection, solar water disinfection, solar distillation, homemade water filters.

Groundwater remediation

Groundwater pollution is much more difficult to abate than surface pollution because groundwater can move great distances through unseen aquifers. Non-porous aquifers such as clays partially purify water of bacteria by simple filtration (adsorption and absorption), dilution, and, in some cases, chemical reactions and biological activity; however, in some cases, the pollutants merely transform to soil contaminants. Groundwater that moves through open fractures and caverns is not filtered and can be transported as easily as surface water. In fact, this can be aggravated by the human tendency to use natural sinkholes as dumps in areas of karst topography.

Pollutants and contaminants can be removed from ground water by applying various techniques thereby making it safe for use. Ground water treatment (or remediation) techniques span biological, chemical, and physical treatment technologies. Most ground water treatment techniques utilize a combination of technologies. Some of the biological treatment techniques include bioaugmentation, bioventing, biosparging, bioslurping, and phytoremediation. Some chemical treatment techniques include ozone and oxygen gas injection, chemical precipitation, membrane separation, ion exchange, carbon absorption, aqueous chemical oxidation, and surfactant enhanced recovery. Some chemical techniques may be implemented using nanomaterials. Physical treatment techniques include, but are not limited to, pump and treat, air sparging, and dual phase extraction.

Abandonment

If treatment or remediation of the polluted groundwater is deemed to be too difficult or expensive then abandoning the use of this aquifer's groundwater and finding an alternative source of water is the only other option.

Society and culture

Examples

Hinkley, USA

The town of Hinkley, California (USA), had its groundwater contaminated with hexavalent chromium starting in 1952, resulting in a legal case against Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) and a multimillion-dollar settlement in 1996. The legal case was dramatized in the film Erin Brockovich, released in 2000.

Walkerton, Canada

In the year 2000, groundwater pollution occurred in the small town of Walkerton, Canada leading to seven deaths in what is known as the Walkerton E. Coli outbreak. The water supply which was drawn from groundwater became contaminated with the highly dangerous O157:H7 strain of E. coli bacteria.[35] This contamination was due to farm runoff into an adjacent water well that was vulnerable to groundwater pollution.

Lusaka, Zambia

The peri-urban areas of Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, have ground conditions which are strongly karstified and for this reason – together with the increasing population density in these peri-urban areas – pollution of water wells from pit latrines is a major public health threat there.[33]

References[17]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wolf, L., Nick, A., Cronin, A. (2015). How to keep your groundwater drinkable: Safer siting of sanitation systems – Working Group 11 Publication. Sustainable Sanitation Alliance

- ↑ Wolf, Jennyfer; Prüss-Ustün, Annette; Cumming, Oliver; Bartram, Jamie; Bonjour, Sophie; Cairncross, Sandy; Clasen, Thomas; Colford, John M.; Curtis, Valerie; De France, Jennifer; Fewtrell, Lorna; Freeman, Matthew C.; Gordon, Bruce; Hunter, Paul R.; Jeandron, Aurelie; Johnston, Richard B.; Mäusezahl, Daniel; Mathers, Colin; Neira, Maria; Higgins, Julian P. T. (August 2014). "Systematic review: Assessing the impact of drinking water and sanitation on diarrhoeal disease in low- and middle-income settings: systematic review and meta-regression". Tropical Medicine & International Health. 19 (8): 928–942. doi:10.1111/tmi.12331.

- ↑ Buitenkamp, M., Richert Stintzing, A. (2008). Europe's sanitation problem – 20 million Europeans need access to safe and affordable sanitation. Women in Europe for a Common Future (WECF), The Netherlands

- ↑ Lynda Knobeloch; Barbara Salna; Adam Hogan; Jeffrey Postle; Henry Anderson (2000). "Blue Babies and Nitrate-Contaminated Well Water". Ehponline.org. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ M. Nasir Khan and F. Mohammad "Eutrophication: Challenges and Solutions" in A. A. Ansari, S. S. Gill (eds.), Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences and Control, Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7814-6_5

- ↑ C. J. Rosen; B. P. Horgan (9 January 2009). "Preventing Pollution Problems from Lawn and Garden Fertilizers". Extension.umn.edu. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ↑ "Journal of Contaminant Hydrology – Fertilizer-N use efficiency and nitrate pollution of groundwater in developing countries". Journal of Contaminant Hydrology. 20: 167–184. doi:10.1016/0169-7722(95)00067-4. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ↑ "NOFA Interstate Council: The Natural Farmer. Ecologically Sound Nitrogen Management. Mark Schonbeck". Nofa.org. 25 February 2004. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ↑ Roots, Nitrogen Transformations, and Ecosystem Services Annual Review of Plant Biology Vol. 59: 341–363

- ↑ World Health Organization (2004). "Fluoride in drinking-water" (PDF).

- ↑ DVGW (2006) Guidelines on drinking water protection areas – Part 1: Groundwater protection areas. Bonn, Deutsche Vereinigung des Gas- und Wasserfaches e.V. Technical rule number W101:2006-06

- ↑ Nick, A., Foppen, J. W., Kulabako, R., Lo, D., Samwel, M., Wagner, F., Wolf, L. (2012). Sustainable sanitation and groundwater protection – Factsheet of Working Group 11. Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA)

- 1 2 Graham, J.P., Polizzotto, M.L. (2013). "Pit Latrines and Their Impacts on Groundwater Quality: A Systematic Review.". Environ Health Perspect. 121: 521–530. doi:10.1289/ehp.1206028. PMID 23518813.

- ↑ Philips, P.J.; Chalmers, A.T.; Gray, J.L.; Kolpin, D.W.; Foreman, W.T.; Wall, G.R. "2012. Combined Sewer Overflows: An Environmental Source of Hormones and Wastewater Micropollutants". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Environmental Science and Technology. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Winker, M. (2009). Pharmaceutical residues in urine and potential risks related to usage as fertiliser in agriculture. PhD thesis, Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH), Hamburg, Germany, p. 45, ISBN 978-3-930400-41-6

- ↑ Hydraulic Fracturing Drinking Water Assessment

- 1 2 DiGiulio, Dominic C.; Jackson, Robert B. "Impact to Underground Sources of Drinking Water and Domestic Wells from Production Well Stimulation and Completion Practices in the Pavillion, Wyoming, Field". Environmental Science & Technology. 50 (8): 4524–4536. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b04970.

- ↑ Ellsworth, William (July 12, 2013). "Injection-Induced Earthquakes". Science AAAS.

- 1 2 3 Vengosh, Avner (7 March 2014). "A Critical Review of the Risks to Water Resources from Unconventional Shale Gas Development and Hydraulic Fracturing in the United States". Environmental Science & Technology. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 Howarth, Robert (14 September 2011). "Natural gas: Should fracking stop?". Nature.

- ↑ Drollette, Brian D.; Hoelzer, Kathrin; Warner, Nathaniel R.; Darrah, Thomas H.; Karatum, Osman; O’Connor, Megan P.; Nelson, Robert K.; Fernandez, Loretta A.; Reddy, Christopher M. (2015-10-27). "Elevated levels of diesel range organic compounds in groundwater near Marcellus gas operations are derived from surface activities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (43): 13184–13189. doi:10.1073/pnas.1511474112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4629325

. PMID 26460018.

. PMID 26460018. - ↑ "Fracking Fluids Spill Caused Kentucky Fish Kill". EWG. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- ↑ "Fracking Boom Linked to Increasing Wastewater Spills". Claims Journal. 2015-09-09. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- ↑ "Texas fracking site that spilled 42,000 gallons of fluid into residential area hopes to reopen". RT International. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- ↑ "Lack of data on fracking spills leaves researchers in the dark on water contamination". StateImpact Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Potential Threats to Our Groundwater". The Groundwater Foundation. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ John H. Tellam, Michael O. Rivett, Rauf G. Israfilov, Liam G. Herringshaw (2006). Urban Groundwater Management and Sustainability. Springer Link, NATO Science Series Volume 74 2006. p. 490. ISBN 978-1-4020-5175-3.

- ↑ Groundwater Sampling; http://www.groundwatersampling.org/

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey (USGS), Denver, CO (1998). "Ground Water and Surface Water: A Single Resource." Circular 1139.

- ↑ Nick, A., Foppen, J. W., Kulabako, R., Lo, D., Samwel, M., Wagner, F., Wolf, L. (2012). Sustainable sanitation and groundwater protection – Factsheet of Working Group 11. Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA)

- ↑ ARGOSS (2001). Guidelines for assessing the risk to groundwater from on-site sanitation. NERC, British Geological Survey Commissioned Report, CR/01/142, UK

- ↑ Moore, C., Nokes, C., Loe, B., Close, M., Pang, L., Smith, V., Osbaldiston, S. (2010) Guidelines for separation distances based on virus transport between on-site domestic wastewater systems and wells, Porirua, New Zealand, p. 296

- 1 2 Ground Water Rule (GWR) | Ground Water Rule | US EPA. Water.epa.gov. Retrieved on 2011-06-09.

- ↑ "Pollution of groundwater". Water Encyclopedia, Science and Issues. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ "Walkerton E. coli outbreak declared over". Tracy McLaughlin , The Globe and Mail.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Underground water. |

- USGS Office of Groundwater

- UK Groundwater Forum

- IGRAC, International Groundwater Resources Assessment Centre

- IAH, International Association of Hydrogeologists

- Argoss Project of British Geological Survey

- Groundwater pollution and sanitation (documents in library of the Sustainable Sanitation Alliance)

- UPGro – Unlocking the Potential of Groundwater for the Poor