Indoor air pollution in developing nations

Indoor air pollution in developing nations is a significant form of indoor air pollution (IAP) that is little known to those in the developed world.

Three billion people in developing nations across the globe rely on biomass, in the form of wood, charcoal, dung, and crop residue, as their domestic cooking fuel. Because much of the cooking is carried out indoors in environments that lack proper ventilation, millions of people, primarily poor women and children face serious health risks. Globally, 4.3 million deaths were attributed to exposure to IAP in developing countries in 2012, almost all in low and middle income countries. The South East Asian and Western Pacific regions bear most of the burden with 1.69 and 1.62 million deaths, respectively. Almost 600,000 deaths occur in Africa, 200,000 in the Eastern Mediterranean region, 99,000 in Europe and 81,000 in the Americas. The remaining 19,000 deaths occur in high income countries.[WHO 1]

Even though the rate of dependence on biomass fuel is declining, this dwindling resource will not keep up with population growth which could ultimately put environments at even greater risk.

Over the past several decades, there have been numerous studies investigating the air pollution generated by traditional household solid fuel combustion for space heating, lighting, and cooking in developing countries. It is now well established that, throughout much of the developing world, indoor burning of solid fuels (biomass, coal, etc.) by inefficient, often insufficiently vented, combustion devices results in elevated exposures to household air pollutants. This is due to the poor combustion efficiency of the combustion devices and the elevated nature of the emissions. In addition, they are often released directly into living areas.[1] Smoke from traditional household solid fuel combustion commonly contains a range of incomplete combustion products, including both fine and coarse particulate matter (e.g., PM2.5, PM10), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and a variety of organic air pollutants (e.g., formaldehyde, 1,3-butadiene, benzene, acetaldehyde, acrolein, phenols, pyrene, benzopyrene, benzo(a)pyrene, dibenzopyrenes, dibenzocarbazoles, and cresols).[1] In a typical solid fuel stove, about 6–20% of the solid fuel is converted into toxic emissions (by mass). The exact quantity and relative composition is determined by factors such as the fuel type and moisture content, stove type and operation influencing the amount.[1]

While many pollutants can evolve, most measurements have been focused on breathing-zone exposure levels of particulate matter (PM) and carbon monoxide (CO), which are the main products of incomplete combustion and are considered to pose the greatest health risks. Indoor PM2.5 exposure levels have been consistently reported to be in the range of hundreds to thousands of micrograms per cubic meter (μg/m3). Similarly, CO exposure levels have been measured to be as high as hundreds to greater than 1000 milligrams per cubic meter (mg/m3). A recent study of 163 households in two rural Chinese counties reported geometric mean indoor PM2.5 concentrations of 276 μg/m3 (combinations of different plant materials, including wood, tobacco stems, and corncobs), 327 μg/m3 (wood), 144 μg/m3 (smoky coal), and 96 μg/m3 (smokeless coal) for homes using a variety of different fuel types and stove configurations (e.g., vented, unvented, portable, fire pit, mixed ventilation stove).[1]

Health implications

Rural Kenya has been the site of various applied research projects to determine the intensity of emissions that commonly occur from use of biomass fuels, particularly wood, dung, and crop residue. Smoke is the result of the incomplete combustion of solid fuel which women and children are exposed to up to seven hours each day in closed environments.[2] These emissions vary from day to day, season to season and with changes in the amount of airflow within the residence. Exposure in poor homes far exceeds accepted safety levels by as much as one hundred times over.[2] Because many Kenyan women utilize a three-stone fire, the worst offender, one kilogram of burning wood produces tiny particles of soot which can clog and irritate the bronchial pathways. The smoke also contains various poisonous gases such as aldehydes, benzene, and carbon monoxide. Exposure to IAP from combustion of solid fuels has been implicated, with varying degrees of evidence, as a causal agent of several diseases.[WHO 1] Acute lower respiratory infections (ALRI) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are the leading causes of disease and death from exposure to smoke. Cataracts and blindness, lung cancer, tuberculosis, premature births and low birth weight are also suspected of being caused by IAP.

Women and primarily girls spend excess time each day in collecting fuel-wood in Kenya which exposes them to even further hazards including vulnerability to rape and also fractures from the weight of carrying heavy loads. This time could be spent in more productive ways such as attending school or income production. The use of biomass coupled with inefficient cooking apparatus leads to a web of social and environmental concerns which directly links to the United Nations Millennium Development Goals.

Interventions

Early interventions

Unfortunately, finding an affordable solution to address the many effects of IAP – improving combustion, reducing smoke exposure, improving safety and reducing labor, reducing fuel costs, and addressing sustainability – is complex and in need of continual improvement.[3] Efforts to improve cook stoves in the past, beginning in the 1950s, were primarily aimed at minimizing deforestation with no concern for IAP, though the effectiveness of these efforts to save firewood is debatable. Various attempts had various outcomes. For example, some improved stove designs in Kenya significantly reduced particulate emissions but produced higher CO2 and SO2 emissions. Flues to remove smoke were difficult to design and were fragile.

Improved success

Current improved interventions however, include smoke hoods which operate in much the same manner as flues, to extract smoke, but are found to reduce levels of IAP more effectively than homes that relied solely on windows for ventilation.[4] Some features of newly improved stoves include a chimney, enclosing the fire to retain heat, designing a pot holder to maximize heat transfer, dampers to control air flow, a ceramic insert to reduce heat loss, and multi-pot systems to allow for cooking multiple dishes.

Stoves are now known to be one of the least-cost means to achieve the combined objective of reducing the health burden of IAP and in some areas reducing environmental stress from biomass harvesting.[5] Some success in installation of interventions, including improved cook stoves, has been achieved primarily due to an interdisciplinary approach which includes multiple stakeholders. These projects have discovered that key socio-economic issues must be addressed to ensure the success of intervention programs. A multitude of complex issues indicate improved stoves are not merely a tool to save fuel.

Successful interventions

The following information represents one successful intervention known as the Kenya Smoke and Health Project (1998–2001)[6] which involved fifty rural households in two separate regions, Kajiado and West Kenya. These areas were chosen due to different climate, geographic, and cultural implications. Community participation was the primary focus for this project and as a result, those involved indicated the results far exceeded their expectations. Local women's groups and, in the case of the project in West Kenya, men were actively involved. By involving the end-users the project resulted in more widespread acceptance and created the further benefit of providing local income.

Three key interventions were discussed and disseminated; ventilation by enlarging windows or opening eaves spaces, adding smoke hoods over the cooking area, or the option of installing an improved cook stove such as the Upesi stove. Smoke hoods are free-standing units that act like flues or chimneys in their effort to draw smoke out of the dwelling. They can be used over traditional open fires and this study showed they contribute to considerably lower levels of IAP. The smoke hood models were made with hard manila paper and then transferred to heavy-gauge galvanized sheet metal and manufactured locally. This resulted in further employment opportunities for the artisans who were trained by the project. The Upesi stove, made of clay and kiln-fired, was developed by Practical Action and East African partners to utilize wood and agricultural wastes. Because this stove was designed and adapted for local needs it produced several winning features. Not only does it cut the use of fuel-wood by approximately half, and reduce exposure to household smoke, it also empowers local women by creating employment as they are the ones who make and market the stoves. These women's groups gain access to technical training in production and marketing and enjoy higher wage earnings and improved social status as a result of the introduction of this improved stove.

Various benefits were realized including improved health; the most important aspect to each of the villagers involved. The people reported less internal heat allowing for better sleep, fewer headaches and less fatigue, less eye irritation and coughs and dizziness. Safety increased due to the smoke hoods preventing goats and children from falling into the fire and less soot contamination was observed, along with snakes and rodents not entering the home. Windows allowed for the ability to view cattle from indoors, and also reduced kerosene needs due to improved interior lighting. Overall, the indoor environment improved greatly from various simple things that are taken for granted in modern western homes. Greater indoor light also allows for more income generation for women as they can do beadwork by the window when weather doesn't allow for this work outdoors. Children also benefit from increased lighting for homework.

Interpersonal relationships developed among the women due to the project, and men better supported their wives initiative when the end result benefited them as well. While initial efforts to improve stoves were limited in success, current efforts are more successful due to the recognition that sustainable domestic energy resources are "central to reducing poverty and hunger, improving health…and improving the lives of women and children"[6] The optimal short-term goal in minimizing rural poverty is to provide inexpensive and acceptable solutions to the local people. Not only can stoves contribute to this intervention, but the use of cleaner fuels will also provide further benefits.

Similar improved-stove projects have proven successful in other regions of the world. Improved stoves installed as part of the Randomized Exposure Study of Pollution Indoors and Respiratory Effects (RESPIRE) study in Guatemala were found to be acceptable to the population and produce significant health benefits for both mothers and children.[7] Mothers in the intervention group had lower blood pressure and reductions in eye discomfort and back pain.[8][9] Intervention households were also found to have lower levels of small particles and carbon monoxide.[10] Children in these households also had lower rates of asthma.[11] This initial pilot program has evolved into CRECER (Chronic Respiratory Effects of Early Childhood Exposure to Respirable Particulate Matter), which will attempt to follow children in intervention households for a longer period of time to determine whether the improved stoves also contribute to greater health over the lifespan.[12]

The National Program on Improved Chulhas in India has also had some success in encouraging the use of improved stoves among at-risk populations. Begun in the mid-1980s, this program provides subsidies to encourage families to purchase the longer-lasting chulhas and have a chimney installed. A 2005 study showed that stoves with chimneys are associated with a lower incidence of cataracts in women.[13] Much of the available information from India is more of a characterization of the issue and there is less data available from intervention trials.

China has been particularly successful at encouraging the use of improved stoves, with hundreds of millions of stoves installed since the beginning of the project in the early 1980s. The government very intentionally targeted poorer, rural households, and by the late 1990s nearly 75% of such households contained "improved kitchens."[14] A 2007 review of 3500 households showed an improvement in indoor air quality in intervention households characterized by lower concentrations of small particles and carbon monoxide in household air.[15] The program in China involved intervention on a large scale, but the cost of stoves was heavily subsidized so it is not known if its success could be replicated.

Environmental impacts

Mortality and burden of disease are not the only detrimental effects from utilizing inefficient energy technology such as the combustion of biomass. Kenya's pre-dominant energy source is biomass, providing more than 90 per cent of rural household energy needs, about one-third in the form of charcoal and the rest from firewood.[16] Biomass energy sourced primarily from savannah woodlands includes firewood for inhabitants and charcoal for urban use. A small percentage is sourced by neighboring communities from closed and protected forests which are generally found in high population density areas.[16] While biomass harvesting in sensitive areas is problematic, it is now determined that the great majority of biomass clearing is due to agricultural expansion and land conversion.[5] Approximately 38% of households 'in high agro-ecological zones' utilize agricultural waste due to frequent shortages of conventional fuel-wood.[16] Use of crop residue and animal waste for domestic energy has detrimental results on soil quality and agricultural and livestock productivity. These materials are ultimately not available as soil conditioners, organic fertilizer, and livestock fodder, not to mention the "cumulative effects on national food security".[16]

Most farmers are aware however, that when agricultural waste and dung are not used for energy, they are important elements to maintaining soil fertility. One of the most efficient ways to utilize crop waste and dung for domestic energy is to produce briquettes. The process of compacting the material into a donut shape creates more efficient combustion which contributes to reduced emission levels. A simple device allows for this process and it can be done locally.

Sustainable options

Large-scale combustion of biomass is only feasible if carried out in a sustainable manner. Concern is paramount for regeneration of renewable and sustainable fuel-wood sources if it is to continue to be available long-term. Attempts at sustainable solutions in Kenya could include developing energy crops (trees and shrubs) which would also provide additional income for farmers. This solution would benefit cropland or rangeland prone to erosion and flooding as the root systems and leaf litter would enhance soil stability.[16] Careful selection of regenerating varieties would be most sustainable because soil stability is not disrupted due to tilling and planting. Some people view this solution as a way to further exploit forests, but with proper management of forest resources this could be a viable solution.

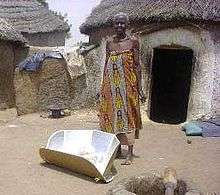

Solar cooking is a sustainable option for reducing the use of biomass as fuel and thereby contribute to the reduction of IAP. Energy Efficient cooking devices such as the Wonderbag can also significantly reduce fuel requirements for residential cooking. Kyoto Twist, an international aid organization has published an excellent case study where two Cookit solar cookers saved families of 6 people 2000 pounds of wood in a year.[17]

Challenges

Widespread education and government funding will also be necessary to shift cultural practices to more sustainable energy use. For example, in an area in South Africa, even though access to electricity was available, many residents continued to use biomass fuels for cooking and heating due to cost of electrical appliances and cultural practices. Liquid petroleum gas (LPG), which has nearly 100% combustion and negligible emissions unfortunately is currently not cost effective. The use of solar power, such as solar cookers, has drawbacks in practical use because they must be used outdoors, and they are slow and do not work in the evening or on cloudy days.

Education interventions

Educational intervention can contribute to reducing exposure to smoke by developing a social marketing effort in alerting people to the dangers and encouraging a willingness to alter living and cultural practices which could have a significant impact on mitigating exposure to IAP. These interventions "must be based on felt needs"[4] with emphasis and sensitivity to gender issues. Evidence of one successful government intervention was revealed by China who, between 1980 and 1995, disseminated 172 million improved cookstoves. This effort proved more successful due to the inclusion of local users, particularly women, who were involved in the design and fieldwork process.

Primary intervention for children

Children up to five years of age spend 90% of their time at home.[18] Globally, 50% of pneumonia deaths among children under five years of age are due to particulate matter inhaled from indoor air pollution.[19] Many homes around the world used solid fuels for cooking. These fuels release large amounts of carbon monoxide and fine particulate matter.[20] These chemical irritants when inhaled may cause different pulmonary conditions ranging from pulmonary epithelial cancer or acute pulmonary tract infection.[21]

Kenya and modern energy

As of 2004, Kenya has shown a willingness to undertake biomass energy issues with the understanding that consumption is associated with indoor air pollution and environmental degradation.[16] Suggestions from the United Nations Development Programme include establishing an institution that will deal exclusively with biomass energy by developing policy guidelines on sustainable firewood, charcoal, and modern biomass such as cleaner fuels and wind, solar, and small scale hydropower. Short-term solutions rest in more efficient domestic energy use by way of improved cook stoves which provide more affordable options in the near future than a complete shift to nonsolid fuels. Long-term solutions rest on transition to modern cleaner fuels and alternative energy sources within a broad international and national policy and economic agenda. Government support for long-term solutions is feasible as witnessed by current efforts in Zambia to develop policy to promote biofuels.

Kenya is the world leader in the number of solar power systems installed per capita (but not the number of watts added). More than 30,000 small solar panels, each producing 12 to 30 watts, are sold in Kenya annually. For an investment of as little as $100 for the panel and wiring, the PV system can be used to charge a car battery, which can then provide power to run a fluorescent lamp or a small television for a few hours a day. More Kenyans adopt solar power every year than make connections to the country's electric grid.[22]

Further action

National and international effort must be stepped up to advance short and long term solutions for the millions of women and children who suffer from poverty and disease as a result of indoor air pollution. Scientists predict the African continent will be the first to experience the effects of global warming where widespread poverty will put millions at further risk due to their limited capabilities to adapt. The potential is great for a more sustainable Africa with commitment from within and outside the region. Pneumonia is the number one killer of children in the world and indoor air pollution is a strongly significant risk factor for severe pneumonia. The global health community designated 2 November to be World Pneumonia Day in order to raise awareness about the disease and its causes.

See also

- Category:Energy by country

- Envirofit

- Guatemala Stove Project

- Rocket stove

- International Association of Certified Indoor Air Consultants (IAC2)

- Rural electrification

- Sick building syndrome

- Renewable energy in China

References

- 1 2 3 4 , Long, C., Valberg, P., 2014. Evolution of Cleaner Solid Fuel Combustion, Cornerstone, http://cornerstonemag.net/evolution-of-cleaner-solid-fuel-combustion/

- 1 2 Smoke's increasing cloud across the globe, Practical Action, accessed 5 May 2007.

- ↑ Duflo E, Greenstone M, Hanna R (2008). "Indoor air pollution, health and economic well-being". S.A.P.I.EN.S. 1 (1).

- 1 2 Health, Environment And The Burden Of Disease: A Guidance Note, Cairncross, S., O'neill, D., McCoy., A., Sethi, D. 2003. DFID. Accessed 10 May 2007.

- 1 2 Healthy Stoves and Fuels for Developing Nations and the Global Environment, Kammen, D. 2003. Accessed 12 May 2007.

- 1 2 Kenya Smoke and Health Project, ITDG. 1998-2001. Accessed 5 May 2007.

- ↑ Department of Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley. Randomized exposure study of pollution indoors and respiratory effects (RESPIRE). http://ehs.sph.berkeley.edu/guat/page.asp?id=15. Accessed 18 March 2008.

- ↑ McCracken JP, Smith KR, Diaz A, Mittleman MA, Schwartz J (July 2007). "Chimney stove intervention to reduce long-term wood smoke exposure lowers blood pressure among Guatemalan women". Environ Health Perspect. 115 (7): 996–1001. doi:10.1289/ehp.9888. PMC 1913602

. PMID 17637912.

. PMID 17637912. - ↑ Diaz E, Smith-Sivertsen T, Pope D, Lie RT, Diaz A, McCracken J, et al. (January 2007). "Eye discomfort, headache and back pain among Mayan Guatemalan women taking part in a randomised stove intervention trial". J Epidemiol Community Health. 61 (1): 74–9. doi:10.1136/jech.2006.043133. PMC 2465594

. PMID 17183019.

. PMID 17183019.

- ↑ Bruce N, McCracken J, Albalak R, Schei MA, Smith KR, Lopez V, et al. (2004). "Impact of improved stoves, house construction and child location on levels of indoor air pollution exposure in young Guatemalan children". J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 14 (Suppl 1): S26–33. doi:10.1038/sj.jea.7500355. PMID 15118742.

- ↑ Schei MA, Hessen JO, Smith KR, Bruce N, McCracken J, Lopez V (2004). "Childhood asthma and indoor woodsmoke from cooking in Guatemala". J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 14 (Suppl 1): S110–7. doi:10.1038/sj.jea.7500365. PMID 15118752.

- ↑ Department of Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley. Chronic respiratory effects of childhood exposure to respirable particulate matter (CRECER). http://ehs.sph.berkeley.edu/guat/page.asp?id=1. Accessed 18 March 2008.

- ↑ Pokhrel AK, Smith KR, Khalakdina A, Deuja A, Bates MN (2005). "Case-control study of indoor cooking smoke exposure and cataract in Nepal and India". Int J Epidemiol. 34 (3): 709–10. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi077. PMID 15833790.

- ↑ Smith, KR. Household monitoring project in China. Environmental Health Sciences Department website. http://ehs.sph.berkeley.edu/hem/page.asp?id=29. Accessed 18 March 2008.

- ↑ Edwards RD, Liu Y, He G, Yin Z, Sinton J, Peabody J, et al. (2007). "Household CO and PM measured as part of a review of China's National Improved Stove Program". Indoor Air. 17 (3): 189–203. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2007.00465.x. PMID 17542832.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Global Village Energy Partnership, Nairobi, Kenya, UNDP. 2005. Accessed 30 April 2007.

- ↑ Kyoto Twist

- ↑ Mukesh Dherani; et al. (May 2008). "Indoor air pollution from unprocessed solid fuel use and pneumonia risk in children aged under five years: a systematic review and meta-analysis no.5 Genebra". Bull World Health Organization. 86 (1): 321–416.

- ↑ Zheng, Li (October 2011). "Evaluation of exposure reduction to indoor air pollution in stove intervention projects in Peru by urinary biomonitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites". Environment International. 37 (7). doi:10.1016/j.envint.2011.03.024.

- ↑ Fullerton, DG.; et al. (September 2008). "Indoor air pollution from biomass fuel smoke is a major health concern in the developing world.". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 102 (9). doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.05.028.

- ↑ Rudan, I. (2004). "Global estimate of the incidence of clinical pneumonia among children under five years of age". Bull World Health Organ [online]. 82 (12).

- ↑ The Rise of Renewable Energy

- 1 2 "Burden of disease from Indoor Air Pollution for 2012" (PDF). WHO. 2014-03-24. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

External links

- World Health Organization Page on Indoor Air Pollution

- Washington Post Article on Indoor Air Pollution in Asia

- IPS story on the Cost of IAP to Women's Health

- Practical Action

- 2 November is World Pneumonia Day