Aristocracy of Norway

Aristocracy of Norway refers to modern and medieval aristocracy in Norway. Additionally, there have been economical, political, and military élites that—relating to the main lines of Norway's history—are generally accepted as nominal predecessors of the aforementioned. Since the 16th century, modern aristocracy is known as nobility (Norwegian: adel).

The very first aristocracy in today's Norway appeared during the Bronze Age (c. 1800 BC – c. 500 BC). This bronze aristocracy consisted of several regional élites, whose earliest known existence dates to c. 1500 BC. Via similar structures in the Iron Age (c. 400 BC – c. 793 AD), these entities would reappear as petty kingdoms before and during the Age of Vikings (c. 793 – 1066). Beside a chieftain or a petty king, each kingdom had its own aristocracy.

Between 872 and 1050, during the so-called unification process, the first national aristocracy began to develop. Regional monarchs and aristocrats who recognised King Harald Halfdanson as their high king, would normally receive vassalage titles like Earl. Those who refused, were defeated or chose to migrate to Iceland, establishing an aristocratic, clan-ruled state there. The subsequent lendman aristocracy in Norway—powerful feudal lords and their families—ruled their respective regions with great independence. Their status was by no means equal to that of modern nobles; they were nearly half royal. For example, Ingebjørg Finnsdottir of the Arnmødling dynasty was married to King Malcolm III of Scotland. During the civil war era (1130–1240) the old lendmen were severely weakened, and many disappeared. This aristocracy was ultimately defeated by King Sverre Sigurdsson and the Birchlegs, after which they were replaced by supporters of Sverre.

Primarily between the 9th century and the 13th century, the aristocracy was not limited to mainland Norway but appeared in and ruled parts of the British Isles as well as Iceland and the Faroe Islands. Kingdoms, city states, and other types of entities, for example the Kingdom of Dublin, were established or possessed either by Norwegians or by native vassals. Other territories, for example Shetland and the Orkney Islands, were directly absorbed into the Kingdom of Norway. For example, the Earl of Orkney was a Norwegian nobleman.

The nobility—known as hird and then as knights and squires—was institutionalised during the formation of the Norwegian state in the 13th century. Originally granted an advisory function as servants of the King, the nobility grew into becoming a great political factor. Their land and their armed forces, and also their legal power as members of the Council of the Realm, made the nobility remarkably independent from the King. At its height, the Council had the power to recognise or choose inheritors of or pretenders to the Throne. In 1440, they dethroned King Eric III. The Council even chose its own leaders as regents, among others Sigurd Jonsson of Sudreim. This aristocratic power, which also involved the Church, lasted until the Reformation, when the King illegally abolished the Council in 1536. This removed nearly all of the nobility's political foundation, leaving them with mainly administrative and ceremonial functions. Subsequent immigration of Danish nobles (who thus became Norwegian nobles) would further marginalise the position of natives. In the 17th century, the old nobility consisted almost entirely of Danes.

After 1661, when absolute monarchy was introduced, the old nobility was gradually replaced by a new. This consisted mainly of merchants and officials who had recently been ennobled, but also of foreign nobles who were naturalised. Dominant elements in the new nobility were the office nobility (noble status by holding high civilian or military offices) and—especially prominent in the 18th century—the letter nobility (noble status via letters patent in return for military or artistic achievements or monetary donations). Based on the 1665 Lex Regia, which stated that the King was to be revered and considered the most perfect and supreme person on the Earth by all his subjects, standing above all human laws and having no judge above his person, [...] except God alone, the King had his hands free to develop a new and loyal aristocracy to honour his absolute reign. The nobilities in Denmark and Norway could, likewise, bask in the glory of one of the most monarchial states in Europe. The titles of baron and count were introduced in 1671, and in 1709 and 1710, two marquisates (the only ones in Scandinavia) were created. Additionally, hundreds of families were ennobled, i.e. without titles. Demonstrating his omnipotence, the monarch could even revert noble status ab initio (as if ennoblement had never happened) and elevate dead humans to the estate of nobles. A rich aristocratic culture developed during this epoch, for example family names like Gyldenpalm (lit. 'Golden Palm'), Svanenhielm (lit. 'Swan Helm'), and Tordenskiold (lit. 'Thunder Shield'), many of them containing particles like French de and German von. Likewise, excessive creation of coats of arms boosted heraldic culture and praxis, including visual arts.

The 1814 Constitution forbade the creation of new nobility, including countships, baronies, family estates, and fee tails. The 1821 Nobility Law initiated a long-range abolition of the nobility as an official estate, a process in which current bearers were allowed to keep their status and possible titles as well as some privileges for the rest of their lifetime. The last legally noble Norwegians died early in the 20th century. Many Norwegians who had noble status in Norway also had it in Denmark, where they remained officially noble.

During the 19th century, members of noble families continued to hold political and social power, for example Severin Løvenskiold as Governor general of Norway and Peder Anker and Mathias Sommerhielm as Prime Minister. Aristocrats were active in Norway's independence movement in 1905, and it has been claimed the union with Sweden was dissolved thanks to a 'genuinely aristocratic wave'. Baron Fritz Wedel Jarlsberg's personal effors contributed to Norway gaining sovereignty of the arctic archipelago Svalbard in 1920. From 1912 to 1918, Bredo Henrik von Munthe af Morgenstierne was Rector of the University of Oslo. When Norway co-founded and entered NATO, ambassador Wilhelm Morgenstierne represented the Kingdom when US President Truman signed the treaty in 1949. Whilst they now acted as individuals rather than a unified estate, these and many other noblemen played a significant public rôle, mainly until the Second World War (1940–1945).

Today, Norway has approximately 10-15 families who were formerly recognised as noble by Norwegian kings. These include Anker, Aubert, Falsen, Galtung, Huitfeldt, Knagenhjelm, Løvenskiold, Munthe af Morgenstierne, Treschow, Werenskiold, and the Counts of Wedel-Jarlsberg. In addition, there exist non-noble families who descend patrilineally from individuals who had personal (non-hereditary) noble status, for example the Paus family and several families of the void ab initio office nobility. There is even foreign nobility in Norway, mainly Norwegian families who originate in other countries and who have or had noble status there.

Primeval aristocracy

Genesis

The earliest times in today's Norway (c. 10000 BC – c. 1800 BC) had a relatively flat social structure, often based on kinship. People were hunters and gatherers who moved over distances in small parties.

However, in the latest part of the Stone Age, some time before 4000 BC, permanent settlements were established in gradually increasing numbers.[1] Before and parallelly with the introduction of agriculture c. 2500 BC, hunter-gatherer societies became larger tribute societies with elements of stratification. Transition to agriculture was both a condition for and triggered the genesis of the very first aristocracy on the Scandinavian Peninsula. The first known aristocracy appeared no later than c. 1500 BC.

Comparatively, transition to agriculture happened c. 9000 BC in the Fertile Crescent and c. 4000 BC in the British Isles. The most obvious reason for Scandinavia's relatively late transition is the Weichsel glaciation, i.e. the latest ice age. Norway was almost wholly covered by ice until c. 7000 BC, and most of the ice sheet was not melted until c. 6000 BC.

Bronze Age

The first known aristocracy in today's Norway existed in the Bronze Age (c. 1800 BC – c. 500 BC) and no later than c. 1500 BC. For this reason, it is called a bronze aristocracy (Norwegian: bronsearistokrati).[2][3] During this age, settlements became more divided into classes as a new dimension appeared: socio-economical differences.

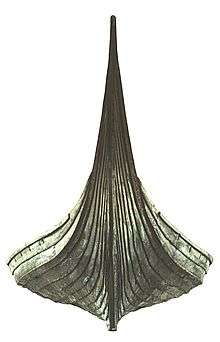

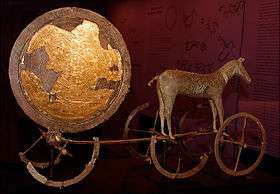

Based on access to and physical control of natural resources, such as furs, walrus teeth, and other goods that were desired by foreigners, a social élite was able to acquire foreign metals. Bronze is essential in this regard. By importing bronze, which they also established a monopoly on, leading persons and their families would not only express their power but even strengthen and increase it. Bronze was also militarily important. It enabled a limited number of possessors to make weapons stronger than those of stone, and unlike the latter, broken bronze weapons could be melted and reshaped. Common people continued to use tools and weapons of stone during the whole age.

Through trade and cultural exchange, the bronze aristocracy was part of the contemporary civilisation in Europe, despite being placed in the geographical outskirts of it.[4] Continental impulses, for example new religious customs and decorative design, arrived relatively early.[5]

Although there was an established aristocracy, the pyramidal social structure is not similar to the feudal system of the much later Medieval Age. Beside other factors, it has been suggested that agricultural production was insufficient to supply an élite that itself did not participate. In general, it is considered as unlikely that the élite possessed total power.[6] Furthermore, power may not only have been based on weapons. Also religious and ancestral factors are important when explaining how certain persons or families managed to maintain authority for generations. For example, impressive burial mounds could consolidate imaginations of a clan's right to an area.

The bronze aristocracy is known primarily through burial mounds, for example a mound (c. 1200 BC) in Jåsund, Western Norway, where an apparently mighty man was buried together with a big bronze sword. Other mounds were filled with bronze weapons and bronze artefacts, for example rings, necklaces, and decorative daggers. The biggest mounds could be up to 8–9 metres in height and 40 metres in diametre.[7] A construction like this required the work of ten men for about four weeks.[8]

The bronze aristocracy faced a challenge when the position of bronze was taken over by iron. Unlike bronze, which remained an aristocratically controlled metal through the whole age, iron was found in rich amounts in the nature, especially in bogs, and was thus owned and used by broader layers of the population.[9]

Early and Late Iron Age

Archaeological examination of graves of the Early Iron Age (c. 400 BC – c. AD 500) has revealed three distinct social strata. Ordinary farmers were cremated and buried in simple, flat graves. (Whilst this sort of burial had existed in the Bronze Age, too, the cremation part was a recently imported custom from Continental Europe—and not imposed on ordinary farmers in particular.) Grand farmers and aristocrats were buried together with grave goods, while chieftains were buried in mounds.[10] Grave goods of this age are dominated by iron artefacts.

In this age, the aristocracy had begun to enslave humans. The use of forced labor in agricultural production made the aristocracy able to spend more resources on military activities, increasing their capacity to control their tax-paying subjects, to defend their territory, and even to expand it. However, thralls were not an aristocratic privilege. In principle, all free men could hold thralls. A thrall was the rightless property of his or her owner. The text Rígsþula identifies three distinct classes and describes extensively how they evolved: chieftains, farmers, and thralls.[11] Religion was used to explain and justify thralldom, but the original motivation was rather economical.

Furthermore, the aristocracy sacrificed humans to be placed in graves of deceased aristocrats. Also this custom was related to religion, i.e. imaginations of life after death. Contemporary sources as well as archaeological remains document this custom. For example, Arab traveller Ahmad ibn Fadlan (fl. 10th century) documented that a female slave was killed for this purpose in a Nordic burial in Russia.

At the beginning of the Late Iron Age (c. 500 – c. 793; in Norway known as the Merovingian Age), there were several changes in Nordic culture: for example the deterioration of the quality of works of art and syncopation of the spoken language. Burial customs in several regions were drastically simplified: stone coffins (stones placed together as a coffin protecting the body within a grave or a tumulus) were no longer used, and tumuli became smaller or were replaced by flat graves. Also grave goods appear to have been lesser in amount than before.

Some historians have interpreted these changes negatively.[12] Some suggest that they were caused by plague or interregional conflict, while others believe that the smaller number of tumuli reflects the consolidation of aristocratic power, which meant that large and splendid monuments were no longer necessary.

Ancient aristocracy

Petty kingdoms

In the last centuries of the Iron Age and at the beginning of the Viking Age (793–1066) petty kingdoms appeared: bigger regional territories with power centres and chieftains. They were the successors of the regional and local entities known from previous ages. Between c. 872—the Battle of Hafrsfjord—and c. 1050, these kingdoms gradually merged into King Harald I Halfdansson's kingdom;—the beginning of today's Kingdom of Norway. In these centuries there were at least about 20 petty kingdoms with their own petty king and aristocracy, such as Agder, Hålogaland, Rogaland, Trøndelag, and Vestfold.

After c. 800 regional aristocracies, especially in Western and Northern Norway, came under bigger pressure from the high king, who used military threats to demand supremacy and tribute. The ancient chieftain's seat at Borg in Northern Norway was among the seats that were abandoned. Refusing to accept King Harald I as their king, many aristocratic families migrated to Iceland: the Settlement of Iceland began in c. 874 and lasted until c. 930.

Unification

In the process of obtaining possession and control over more land (in romantic nationalist terms called the 'unification of Norway'), high kings built their power on cooperation with the aristocracy in each of the former petty kingdoms. In return for recognition of and military support for the King, aristocrats were granted vassalage titles such as Earl (Norwegian: jarl), given to former petty kings and chieftains, and Lendmann, given to ordinary aristocrats.

However, due to a strong clan mentality, these aristocrats' loyalty to the King was weaker than desired, and this represented a threat. That is why the King established a new title, Årmann, which was given to persons of lower origin. These persons, who were the direct vassals of the King, were considered to be more loyal as they did not have the same family allegiance to aristocratic clans. An Årmann would act as a local observer and send reports to the King. This dual set of aristocrats was intended to secure the new monarchical system.

Though aristocratic structures had existed in petty kingdoms, it was during the unification that the first national class of aristocrats began to appear. In the upper classes of this aristocracy were, for example, the Bjarkøy dynasty, previously a dynasty of chieftains in Northern Norway who, having recognised the high king, continued to hold a prominent position for 300 years after the final unification of Norway around 1050, and the Giske dynasty.

It is known that rings of gold were used as royal rewards and as a symbol of a person's royal connection. In the Saga of Olaf the Holy, in Samuel Laing's 1844 translation of Heimskringla by Snorri Sturluson, it says: 'As Kimbe saw that Thormod had a gold ring on his arm, he said, "Thou art certainly a king's man. [...]"'

Lendman aristocracy

Lendmen—powerful feudal lords and de jure vassals of the King— enjoyed considerable independence in ruling their respective territories. Their former position as chieftains was neither forgotten nor completely superseded, and their social position was far higher that of medieval and modern nobility. This was, not least, demonstrated by their many marriages with descendants of kings and chieftains.

Perhaps the most important dynasty was the Arnmødlings (Earl Arnmod and his descendants) from whom the Bjarkøy and Giske dynasties later originated. Arni Arnmodsson, a son of the Earl, had several children, and their marriages illustrate these dynasties' social and political relations. For example, Finn Arnason's daughter Ingebjørg was married first to Torfinn Sigurdsson, Earl of Orkney, and then to King Malcolm III of Scotland, and one of Ingebjørg's sons was King Duncan II of Scotland.[13] One of Finn's granddaughters, Tora Torbergsdotter, was married to King Harald III (c. 1015–1066).

The Sudreim dynasty are also noted for their marriages to royals. Åle Ivarsson, the family's progenitor, was married to a daughter of King Harald IV (died in 1136). Their patrilineal grandson, Sysselmann Olav Mokk, had a son, Baron Jon Ivarsson to Sudreim, whose son Baron Havtore Jonsson married Agnes, a daughter of Haakon V (1270–1319).[14] (See: Sudreim claim.)

The aristocracy of lendmen also operated abroad, mainly in the British Isles. Of the Rein Dynasty, Skule Tostesson took part in King Harald III's invasion of England and in the Battle of Stamford Bridge; as also did Øystein Torbergsson of the Giske Dynasty,[15] a brother-in-law of King Harald.

Among the most prominent aristocrats who participated in crusades were Skofte Agmundsson of the Giske Dynasty,[16] Earl Erling Ormsson of the Arnmødlings, and Ragnvald Kolsson, Earl of Orkney and Shetland and Mormaer of Caithness.

Civil war era

In the decades after the death of King Olaf II in 1030, territorial unity and thus also the throne were consolidated. The secular aristocracy was primarily centered around the new, relatively stable royal power.

There were two potential sources of conflict: kings who died without having produced legitimate male heirs; and the lack of clear rules of royal succession. These tended to cause political and also military conflict between supporters of the various pretenders, subsequently leading to the civil war (1130–1240).

The Lendman Party (Norwegian: lendmannsflokken or lendmannspartiet), which appeared after the 1150s, and its successors, the Baglers, formed in 1196, were movements consisting of members of the secular aristocracy (feudal lords) and of the clerical aristocracy (bishops), among others Earl Erling "the Slanted" Ormsson, who sought to introduce a united hereditary monarchy on the continental European model, preferably with a descendant of Olaf "the Holy" on the throne. The civil war of succession was eventually won by the Birchlegs and the House of Sverre, who thus took over the throne from the previous royal house.

Beginning with the accession of King Sverre in 1184, he and his descendants ousted their enemies who belonged to groups like the Baglers (1196–1217) and the Ribbungs (1219–1227), thus eliminating and replacing considerable parts of the ancient aristocracy. Before battles Sverre had proclaimed to his soldiers that he who killed a lendman should himself become a lendman. Whilst most lendmen disappeared from history, a few former enemies swore loyalty to King Sverre and therefore continued into the medieval aristocracy.

Ancient aristocracy overseas

Primarily between the 9th century and the 13th century, (vassal) kingdoms and earldoms were created overseas. Norwegian aristocracy was thus not limited to mainland Norway but appeared in and ruled parts of the British Isles as well as Iceland and the Faroe Islands. Several entities—kingdoms, city states, tributary territories, etcetera—were established or possessed either by Norwegians or by their vassals. Other territories were directly included in the Kingdom of Norway.

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands were a part of Norway since 1035, when Leivur Øssursson received the islands as a fief from King Magnus I.

Some years earlier Sigmundur Brestisson and his cousin Tóri Beinisson had travelled to the Earl of Norway (de facto king), by whom they were appointed as hirdmen and told to return to the islands. Whilst they did not succeed in taking control of the whole archipelago, they participated in the process that ultimately would bring the Faroe Islands under Norway.

Greenland

One of the first Norwegian aristocrats in Greenland was Icelandic born Leif Eiriksson, who had also grown up there. Leif was a hirdman of King Olaf I. Greenland was a part of Norway since 1261.

Iceland

The process that turned Iceland into a province of Norway began in the 12th century. In the 12th and 13th centuries several Icelanders travelled to and were included at the Royal Court in Norway.

Jón Loftsson, Bödvar Þórðarson, Órmur Jónsson, Oddur Gissursson, and Gissur Hallsson are described as men "whom God has given the power over the people of Iceland" in a letter of 1179 or 1180 from Eysteinn Erlendsson, Archbishop of Norway.[17] Illustrating the growing connection between Iceland and Norway, Jón was the son of Þóra Magnúsdóttir, a daughter of King Magnus III.

In 1220 Snorri Sturluson, an adopted son of Jón and a member of the Sturlunga family, became a vassal of Haakon IV. In 1235 Snorri's nephew Sturla Sighvatsson also accepted vassalage under the King of Norway. Unlike his uncle, Sturla worked actively to bring Iceland under the Norwegian Crown, and waged war on chieftains who refused to accept the King's demands. However, Sturla and his father Sighvatr Sturluson were defeated by Gissur Þorvaldsson, the chief of the Haukdælir, and Kolbeinn the young, chief of the Ásbirnings, in the Battle of Örlygsstaðir, losing their position as the mightiest chieftains in Iceland. Iceland became a part of Norway in 1262, when it became an earldom under Gissur Þorvaldsson.

Northern Islands (Shetland and Orkney)

Norwegians arrived in the Shetland islands in the 8th century, and by 900 they had become lords there. Until 1195 the islands were part of the Earldom of Orkney. After the Battle of Florvåg in that year, Shetland was included in the Kingdom.

Norwegians arrived in the Orkney Islands in the 9th century. The Earldom of Orkney was established at this time, and until 1470 the Earls of Orkney were vassals of the Kings of Norway. The Mormaerdom of Caithness, attached to the Earldom of Orkney, was established in the 10th century, and was connected to Norway until 1476.

In the 1266 Treaty of Perth, Scotland recognised Norwegian sovereignty over Shetland and the Orkney Islands. In 1468 and 1469 King Christian I pledged Shetland and the Orkney Islands to Scotland. Despite a clause that gave future kings of Norway the right to redeem the islands for a fixed sum of gold or silver, Scotland illegally refused to accept several attempts at redemption in the 17th and the 18th centuries.

Southern Islands (Mann and the Isles)

The Kingdom of Mann and the Isles was established in 836.

With the 1266 Treaty of Perth, Mann and the Isles were transferred to Scotland.

Ireland

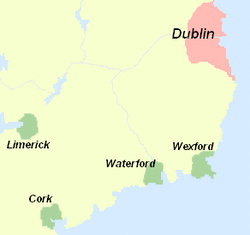

The Kingdom of Dublin was established in 839.

In addition to the Kingdom of Dublin, several city states were established: Cork, Limerick, Waterford, and Wexford.

Various

Some aristocratic families in the British Isles are of Norse origin, among others the Cotter family in Ireland.

Medieval secular aristocracy

The medieval secular aristocracy was originally known as hird, then as knighthood, and since the 16th century under the term adel (English: nobility). There were also other terms, such as 'free men'. The group of persons and families who constituted the medieval aristocracy may be traced back to the time of the formation of the Norwegian state in the 13th century. Not later than during King Magnus VI's reign, the secular aristocracy can be said to be identical with the King's hird.[18] Some of these families had their origin in the ancient aristocracy. Others were recruited based on their ability to provide services to the King.

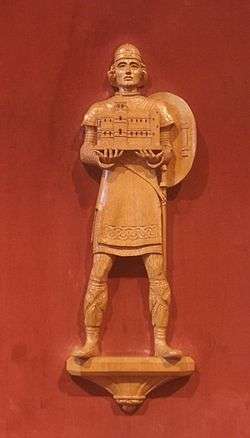

Hird

The hird was divided into three classes, of which the first had three ranks. The first class was hirdmann with lendmann as the 1st rank, skutilsvein as the 2nd rank, and ordinary hirdmann as the 3rd rank. Below them were the classes gjest and kjertesvein.[19][20][21]

Lendmen, having the first rank in the group of hirdmen, had the right to hold 40 armed housecarls, to advise the King, and to receive an annual payment from the King. They normally also held the highest offices in the state. The foundation for their rights was the military duty which their title imposed.

Kjertesveins were young men of good family who served as pages at the court, and gjests constituted a guard and police corps. In addition, there was a fourth group known as housecarls, but it remains uncertain whether they were considered a part of or rather served the hird.

The hird's organisation is described in the King’s Mirror and the Codex of the Hird.

The system of hirdmen—regional and local representatives for the King—was stronger and lasted longer in the tributary lands Shetland, Orkney, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands, and also in Jemtland,[19] originally an independent farmer republic which Norwegian kings used much time and efforts to gain control over.

Knighthood

During the second half of the 13th century continental European court culture began to gain influence in Norway. In 1277 the King introduced continental titles in the hird: lendmen were called barons, and skutilsveins were called ridder.[18] Both were then styled Herr (English: Lord). In 1308 King Håkon V abolished the lendman/baron institution, and it was probably also during his reign that the aristocracy seems to have been restructured into two classes: ridder (English: knight) and væpner (English: squire).[18]

It is difficult to determinate exactly how many knights and squires there were in the 14th and the early 15th century. When King Haakon V signed a peace treaty with the Danish king in 1309, it was sealed by 29 Norwegian knights and squires. King Haakon promised that additional 270 knights and squires would give their written recognition. This were perhaps the approximate number of knights and squires at this time.[22]

Black Death

The Black Death, which came to Norway around 1349, was bad for the nobility. In addition to the loss of their own members, about two thirds of the population were killed by the plague, and the reduction in available manpower for agriculture caused an economic crisis.

The aristocracy was reduced from about 600 families or 3,600 people before 1350 to about 200 families or 1,000 people in 1450.

The value of land was reduced by 50%–75%, and the land rent was reduced by up to 75%, except in relatively populous central districts like Akershus and Båhus, where the reduction was about 40%. The tithe also reduced by 60%–70%.

Both before and after the plague, Norwegian noblemen were unusually dependent on the King compared with noblemen in other countries. Mountainous Norway has never been conducive to large land estates of continental size. As a consequence of the tremendous reduction in land-related income following the plague, it became even more necessary than before to enter royal service.

Militarily, the Black Death was a catastrophe. As lower and local noblemen were killed by the plague, the recruitment of officers and troop leaders was equally reduced. Having lost their economic base (reduced income of taxes etc.) and their economic guarantees from the King, local aristocrats could often not fulfil their military duties.

Fiefs and fortresses

The system of royally controlled fiefs was established in 1308, replacing the originally more independent lendmen. There were two types of medieval fiefs:

To the first belonged castle fiefs (Norwegian: slottslen) or main fiefs (Norwegian: hovedlen), to which the King appointed lords, and under them petty fiefs (Norwegian: smålen), which had varying connections with their respective castle fief. In the 15th century, there were approximately fifty fiefs in Norway. In the late 16th century and the early 17th century, there were four permanent castle fiefs and approximately thirty small. Thereafter, the amount of petty fiefs was reduced in favour of bigger and more stable main fiefs. Lords of castle fief resided in the biggest cities, where the royal farms or the castles were located.[23]

The second type were estate fiefs (Norwegian: godslen), i.e. private, noble estates that constituted independent areas of jurisdiction.[23]

Likewise, nobles were active in the Kingdom's military defence, in which fortresses had a central position. In the early 14th century, the Fortress of Vardøhus in Northern Norway was constructed due to conflicts with the Russian Republic of Novgorod and as protection against robbery raids of the Karelians. The fortresses Bohus and Akershus in Eastern Norway were established approximately at the same time. An earlier fortress was Bergenhus in Western Norway. There would usually be one or more fiefs attached to each fortress. All fortresses were mainly under the command of nobles, who held the military title of høvedsmann.

Time of greatness

During the 14th century members of the hird continued in various directions. The lower parts of the hird lost importance and disappeared. The upper parts, especially the former lendmen, became the nucleus of the nobility of the High Medieval Age: the Knighthood (Norwegian: Ridderskapet). They stood close to the King, and as such they received seats in the Council of the Kingdom as well as fiefs, and some had even family connections to the royal house. There was a significant social distance between the Knighthood and ordinary noblemen.

The Council of the Kingdom was the Kingdom's governing institution, consisting of members of the upper secular and the upper clerical aristocracy, including the Archbishop. Originally, in the 13th century, having had an advisory function as the King's council, the Council became remarkably independent from the King during the 15th century. At its height it had the power to choose or to recognise pretenders to the Throne, and it demanded an electoral charter from each new king. Sometimes it even chose its own leaders as regents (Norwegian: drottsete or riksforstander), among others Sigurd Jonsson (Stjerne) to Sudreim and Jon Svaleson (Smør).

In Norway as well as in Denmark and Sweden, it was in this period that the idea and the principle of riksråd constitutionalism had arisen, i.e. that the Council was considered as the real foundation of sovereignty. Although kings were formal heads of state, the Council was powerful. Their power and active rulership, especially as regents, have caused historians characterise this state as de facto a republic of the nobility (Norwegian: adelsrepublikk).[24][25]

This aristocratic power lasted until the Reformation, when the King in 1536 illegally abolished the Council. The reign of aristocrats was over when Archbishop Olav Engelbrektsson, who was also noble, the Council's president and the Regent of Norway, left the Kingdom in 1537.[24]

Between reformation and absolutism

Following the abolition of the Norwegian Council of the Kingdom in 1536, which de facto ceased to exist in 1537, the nobility in Norway lost most of its formal political foundation. The Danish Council of the Kingdom took over the governing of Norway. However, the nobility in Norway, now confined to more administrative and ceremonial functions, continued to take part in the country's official life, especially at homages to new kings.

Having defeated the aristocratic and besides Roman Catholic resistance in Norway, the King in Copenhagen sought to secure and consolidate his control in the Kingdom. Strategical actions would further weaken the nobility in Norway.

First of all, the King sent Danish noblemen to Norway in order to administer the country and to fill civilian and military offices. Norwegian noblemen were deliberately under-represented when new high officials were appointed. Whilst this was a part of the King’s tactics, also the lack of Norwegian noblemen with qualified education—Norway did not have a university—was a reason for that the King had to send foreigners. The educational sector was considerably better developed in Sleswick and Holsatia, plus in Germany, so only nobles who sent their children to foreign universities could hope to keep or obtain high offices.

Secondly, during the 16th century the system of independent, family-possessed estates as power centra, like Austrått, was ultimately replaced in favour of fiefs to which the King himself appointed lords. A few Norwegian noblemen were given such fiefs, for example Knight Trond Torleivsson Benkestok, Lord to Bergenhus Fortress, but over time these would find themselves possessed almost exclusively by immigrants. Nevertheless, during the 17th century fiefs were transformed into high offices. Also they were considered too risky for the King.

Thirdly, in 1628 the King instituted a national army of soldiers recruited directly from the estate of farmers. At the same time technical development made traditional military methods outdated. As a result, the nobility was defunctionalised in this aspect.

Absolutism

In 1660, when Denmark's estates were gathered in Copenhagen, King Frederick III declared military state of emergency and closed the capital city, thus preventing the nobility from boycotting the assembly by leaving. The nobility was forced to surrender. In the following days, Denmark was transformed from an elective monarchy into an hereditary. On 17 October, the 1648 håndfestning was returned to the King, and on 18 October, the King was hailed as an hereditary monarch. On 10 January 1661, the Absolute and Hereditary Monarchy Act (Norwegian: Enevoldsarveregjeringsakten) introduced absolutism. In Denmark, the Council of the Kingdom faced the same destiny as the Norwegian Council had done in 1536: abolition. The noble monarchy (Norwegian: adelsmonarki) had come to an end.

Formally a hereditary kingdom since old ages, Norway was not affected by Denmark's transition to the same. However, also Norway was affected by absolutism. On 7 August 1661 in Christiania, representatives of the Norwegian nobility signed the Sovereignty Act.[26]

Extinction

.jpg)

The native aristocracy was extensively reduced during the last part of the Late Medieval Age. Several factors may explain this.

An important factor is that families did not produce a sufficient amount of male descendants. As noble status was inherited patrilineally, the lack of men lead to families’ extinction. A reason is that noblemen as warriors were exposed to greater risks than the population in general and therefore died in a young age and without issue.

Another factor is that the Norwegian nobility to a large extent married persons of the estate of commoners. So-called unequal marriages, of which there came to be many especially in lower parts of nobility, led (after 1582 and 1591) to the loss of noble status, noble estates, and similar. In an application to the King in 1591, the nobility requested that since it ‘[...] often [happens] that noblemen here in Norway marry unfree women, and their children inherit his estate, [...] which is the nobility to reduction and shame [...]’,[27] their children should not inherit noble status or noble estate.

It is also a factor that noble status not automatically was inherited. If a family for generations no longer provided services to the King, they could due to oblivion lose their position. An example is the Tordenstjerne family, whose members in the 16th century were squires, but who due to political and military inactivity in the 17th century had to get their noble status confirmed in the 18th century.

It is often claimed that the old nobility ‘died out’ in the Late Medieval Age. This is mostly but not entirely correct. The term ‘extinction’ includes not only families dying out physically, but also disappearance from the written sources of formerly noble families which had lost their political power and importance. This has even obscured the link between the such families before and in the 16th century and their farmer descendants who appear in sources beginning in the late 17th century. In other words, families of the old nobility may in actuality have survived without knowing it or being able to prove it.

The nobility of the 16th century was of a marginal size, thus being socially more exclusive, but also politically more vulnerable. For example, after the Reformation in 1536, the number of nobles was reduced from approximately 800 and to approximately 400, i.e. under 0.2 percent of the population and approximately 1/7 of the size of the Danish nobility.[18] After 1536, only 15 percent of Norwegian land was in noble possession.[18]

Women and women's rights

There are a few examples of medieval noblewomen who acted with considerable de facto independence. Prominent are Lady Ingegjerd Ottesdotter Rømer of Austrått and Lady Gørvel Fadersdotter (Sparre) of Giske. It is, however, important to know that they acted as so-called 'pseudo men', i.e. in the formal rôle of a man (usually their deceased husband's, father's or brother's).[28] Legally, there was no such thing as formal female rôles.

In general, noblewomen had larger economical freedom than women of unfree estate. Whilst the Land Law of 1274 and the Town Law of 1276 gave farmer women and burgher women only limited contol of their assets, noblewomen could buy and sell as much as they pleased.[28] This estate-based discrimination would last until the Land Law (including the Norwegian Code of 1604, which was mostly a Danish translation) was replaced by the Norwegian Code of 1687, a law that made all non-widowed women legally minor, regardless of their birth. (Some minor restrictions were introduced in 1604, when Norwegian law, granting unmarried women financial independence from their 21st year, was adjusted to match Danish law, which imposed lifelong guardianship on women and their fortune.)[28]

The noble privileges of 1582 decreed that a noblewoman who married a non-noble man should lose all her hereditary land to her nearest co-inheritor, for example her brother. The rule was designed with the intention of keeping noble land in noble hand, which would strengthen the nobility's power base.

Medieval secular aristocracy overseas

Faroe Islands

The hird in the Faroe Islands is mentioned for the last time in a document of 1479.

Iceland

In 1262, Gissur Þorvaldsson († 1268) was given the title Earl of Iceland, indicating and imposing that he should rule Iceland on behalf of Norway’s king. It is known that approximately 20–30 Icelandic men had the title of knight in the following centuries, among others Eiríkur Sveinbjarnarson in Vatnsfjörður († 1342) and Arnfinnur Þorsteinsson († 1433).[29][30]

In 1457, King Christian I ennobled Björn Þorleifsson. The same honour had been granted Torfi Arason in 1450. Björn was hirðstjóri (a high royal official) in Iceland and as well the richest man in this part of Norway.

In 1488, King John ennobled Eggert Eggertsson, Lawspeaker (Norwegian: lagmann) of Viken in mainland Norway. His son was Hans Eggertsson (fl. 1522), city administrator (Norwegian: rådmann) of Bergen, and the latter's son was Eggert Hansson, Lawspeaker (Icelandic: lögmaður) of Iceland (fl. 1517–1563). This family is known as Norbagge today.[31]

In 1620 at the Althing, Jón Magnússon the Elder, let a letters patent of 1457 be read, originally given to his aforementioned ancestor Björn Þorleifsson. King Christian IV recognised his noble status. It is claimed that Jón was the last Norwegian nobleman in this part of Norway. The era of the nobility in Iceland ended in 1661 with the introduction of absolutism in Norway.

Medieval secular aristocracy – clerical section

Members of the royal clergy (Norwegian: kongelig kapellgeistlighet), i.e. the clergy of the King's own chapels, which were subordinate only to the King and largely independent of the Church hierarchy in Norway, belonged to the secular aristocracy by virtue of their offices in the service of the King.

In a royal proclamation of 22 June 1300[32] King Haakon V granted St Mary's Church, Oslo—the royal chapel—numerous privileges and decreed that "the learned man who is or becomes its dean" (i.e. the provost) ex officio would have the rank of a lendman, whilst priests with prebends (i.e. the canons) would have the rank of a Knight, the vicars and deacons would have the rank of an (ordinary) hirdmann, and other clerics would have the rank of a kjertesvein; the clergy of this church thus received extraordinarily high aristocratic ranks, according to Sverre Bagge.[33][34]

In 1314 King Haakon decreed that the provost of St Mary's Church would also hold the office of Chancellor (Norwegian: Norges Rikes kansler) and Keeper of the Great Seal ‘for eternity’, and with some interruptions the office of Chancellor was tied to the office of provost of St Mary's Church until some years after the Reformation in 1536. One of the other priests (typically a canon) would serve as Vice-Chancellor according to the royal letter.[35] The main Great Seal was brought to Denmark in 1398, but the Chancellor kept an older version of the seal that was used until the 16th century. The vicars of St Mary's Church probably had a higher position than elsewhere due to their extraordinary aristocratic rank. In 1348 King Haakon VI found it necessary to stress that the canons had higher rank in every aspect and they alone should administer the estate of their church.[36]

St Mary's Church was an important political institution until the Reformation era, as it was the seat of government in Norway, although from the late 14th century effectively subordinate to the central government administration in Copenhagen and increasingly concerned only with matters relating to the legal field.[37] Peter Andreas Munch has described the royal clergy as a counterweight to the (regular) secular aristocracy with a stronger loyalty to the king and a stronger service element than both the (regular) secular and the clerical aristocracy.[38] The cathedral chapter of St Mary's Church ceased to exist as a separate institution when it was merged with the chapter of Oslo Cathedral in 1545, although its clergy retained their prebends.

Most of the royal clergy—especially those who rose to its upper echelons, such as canon and provost—were recruited from the lower nobility and sometimes even from the higher nobility.

In the years following the Reformation, this royal clergy gradually disappeared, as the entire church hierarchy came directly under the King's control. Some remnants of the institution survived for some time; for example the estate of the provost of St Mary's Church (Mariakirkens prostigods) was customarily given as a fief to the Chancellor of Norway until the 17th century.[39]

Hans Olufsson (1500–1570), who was a canon at St Mary's Church before and after the Reformation and who held the prebend of Dillevik that included the income of 43 ecclesiastical properties, is regarded as the probable progenitor of the still extant Paus family.[40]

Medieval clerical aristocracy

The clergy (Norwegian: geistlighet) was one of normally three estates in the Norwegian feudal system. Together with the King and the secular aristocracy, the Archbishop and the clerical aristocracy constituted the power class in the Kingdom. Until the Reformation in 1536 this aristocracy operated and developed in parallel with the secular aristocracy.

It was in the years after the death of King Olaf 'the Holy' in 1030 that Norway was finally Christianised, whereby the Church gradually began to play a political rôle. Already in 1163 the Law of Succession stated that Norwegian kings were no longer sovereign monarchs but vassals holding Norway as a fief from Saint Olaf alias the Eternal King of Norway. This invention gave the Church bigger control of the royal power, not least because the King had to proclaim loyalty to the Pope. King Magnus V (1156–1184) was as such the first of Norway's kings to use the style 'by the Grace of God'. Nevertheless, this law of succession would last only for a century, when a new and for kings more independent law of succession was introduced.

The Church was actively involved in the civil war era (1130–1240), in which they were allies of the established aristocracy and supported throne pretenders who were (alleged) descendants of 'Olaf the Holy'. Ultimately the Church supported Magnus Erlingsson (1156–1184), the son of Earl Erling Ormsson and Princess Kristin Sigurdsdotter.

In 1184, having defeated King Magnus, Sverre Sigurdsson became King of Norway. Subsequently Sverre demanded that the Archbishop should be subordinate to the King. As a result of this King Sverre was excommunicated. In Denmark exiled Archbishop Eirik, plus the majority of bishops, arranged a resistance movement known as the Baglers. They managed to re-occupy and control parts of Eastern Norway, from where they represented a permanent threat to King Sverre. Upon King Sverre's death in 1202 a it became possible to find a compromise between Sverre's supporters, the Birchlegs, and the Archbishop. In 1217 they managed to agree upon a king: King Haakon IV, a paternal grandson of King Sverre.

During the 13th century there were power struggles between the Church and the King. Several disagreements were temporarily solved with the Concordat of Tunsberg (Norwegian: Sættargjerden) of 1277. This concordat granted the clerical aristocracy several rights and privileges or confirmed existing ones, for example the freedom to trade and the freedom from paying lething. The same concordat gave the Archbishop the right to have 100 sveins (armed pages), whilst each bishop could have 40.

Bishops

There were ten bishops under the Archbishop of Nidaros, namely:

- Bishop of Bergen

- Bishop of Stavanger

- Bishop of Oslo

- Bishop of Hamar

- Bishop of Garðar (Greenland)

- Bishop of Skálholt (Iceland)

- Bishop of Hólar (Iceland)

- Bishop of Kirkjubøur (Faroe Islands)

- Bishop of Kirkwall (Orkney Islands)

- Bishop of Mann and the Isles (Mann and the Isles)

Canons

Canons (Norwegian: kannik) were priests who were also attached to one of the dioceses in Norway.

Canons were recruited primarily from the secular aristocracy. Whilst most canons came from the lower nobility, several belonged to the higher nobility by birth. The latter were sons of knights and even of Councillors of the Kingdom. Examples are Jakob Matsson of the Rømer family, Henrik Nilsson of the Gyldenløve family, and Elling Pedersson of the Oxe family.

In the 13th century canons were styled Sira (compare with English Sir).[41]

Priests

Priests (Norwegian: prest) constituted the local level of the clergy.

Originally a style for canons in the 13th century, priests were styled Sira in and after the 14th century.[41] Subsequently Sira was replaced by Herr. Sira and Herr were used in combination with the given name only, e.g. 'Sira Eirik'.

Setesveins

Beside the clerical hierarchy, the Archbishop of Nidaros had his own organisation of officers and servants.

Regional representatives of the Archbishop, setesveins (not to be confused with the noble title of skutilsvein) were seated mainly along the coast of Western and Northern Norway as well as in Iceland. A register of 1533 shows that there were at least 69 setesveins at this time. Their function was to administer the land estate of and to collect the taxes belonging to the Archbishop, and they also traded partly themselves and partly on behalf of the Archbishop.[42] In Northern Norway, a typical location of setesveins was a central position with immediate control of the lucrative fisheries.

Some setesveins belonged to the secular aristocracy too, usually by birth.[42]

After the Reformation in 1536, when King Christian III prohibited the Roman Catholic Church and the Archbishop went into exile, the King punished setesveins who had supported the Archbishop.[42] Many of them had their houses robbed as the King and his soldiers raided the coast.

In Northern Norway ex-setesveins and their descendants were known as page nobility (Norwegian: knapeadel).

Modern aristocracy

The modern aristocracy is known as adel (English: nobility). The parts of the nobility that are regarded as new in Norway consisted of immigrated persons and families of the old nobility of Denmark, of recently ennobled persons and families in Norway as well as in Denmark, and of persons and families whose (claimed) noble status was confirmed or—for foreigners—naturalised by the King.

An absolute monarch since 1660, the King could ennoble and for that sake remove the noble status of anyone he wished and—unlike earlier—without approval from the Council of the Kingdom. He could even elevate dead humans to the estate of nobles. For example, four days after his death in 1781, Hans Eilersen Hagerup was ennobled under the name de Gyldenpalm. This made as well his legitimate children and other patrilineal descendants noble.

In particular there were two ways of receiving noble status: via an office (informally known as office nobility) and via a letters patent (informally known as letter nobility).

On 25 May 1671 King Christian V created 31 counts and barons. As such two classes were created in addition to the class of nobles: the class of barons (Norwegian: friherrestand) and the class of counts (Norwegian: grevestand). A noble was per definition untitled, and barons and counts did not belong to the class of nobles, but to their respective classes.[43] However, all three constituted the estate of nobles. Barons and counts could be either titular or feudal. The latter constituted the feudal nobility (Norwegian: lensadel). On 22 April 1709 King Frederick IV introduced the title of marquis.

The introduction of the titles of count and baron was controversial in the old nobility, who were old enemies of royal absolutism and whom the titles sought to outrank. One reaction was the anonymously published theatre play Comedy of the Count and the Baron, written in 1675.

Office nobility

A minor but nevertheless considerable element of the modern aristocracy was the office nobility (Norwegian: embetsadel or embedsadel, also called rangadel). It was introduced in 1679 and would, with extensive reductions during the 18th century, last until 1814.

A person holding a high-ranking office within one of the highest classes of rank automatically received ennoblement for himself, for his wife, and for his legitimate children, and for decades this status was normally hereditable for his patrilineal and legitimate descendants.[44] However, basically all such ennoblements were annulled when King Christian VI, tired of his father's generosity, acceded to the throne in 1730, and only those who received a special recognition after making an application retained their noble status.[18] The office nobility as such was not abolished. Subsequent royal decrees introduced a more restrictive policy, under which noble status dependent on offices was limited to the person concerned, to his wife, and to his legitimate children.[18]

The Decree on the Order of Precedence of 1671 was radical, for the first time deciding that the nobility did not automatically have the highest rank in the Kingdom. It stated explicitly that the nobility should enjoy their traditional rank above other estates and subjects unless the latter were specified in the order of precedence. In other words, any person within the rank stood above noble persons outside this. The Noble Privileges of 1661 had stated the opposite, namely that the nobility should enjoy rank and honour above all others.[45]

Finally, the Letter of Privileges of 11 February 1679 introduced automatical noble status for the highest members of the order of precedence. As such the office nobility had been established. The letter stated explicitly that these persons of rank as well as wife and children should enjoy all privileges and benefits that others of the nobility had in the present and in the future, and it was also stressed that they should be honoured, respected, and regarded equally with nobles of birth.

The office nobility has later been considered with lesser regard, and for example the Yearbook of the Danish Nobility does not include such persons and families.

Examples:

- Mathias de Tonsberg, who was automatically ennobled in 1704 when he became Councillor of the State (Norwegian: etatsråd).[46]

- Hans Eilersen Hagerup, who was automatically ennobled in 1761 when he became General Commissioner of War.[47] (In 1781 he was even ennobled by letter.)

Letter nobility

Beginning already in the High Medieval Age but especially associated with the late 17th century and the 18th century, it became customary to ennoble persons by letters patent (Norwegian: adelsbrev) for significant military or artistic achievements, and there were also persons who were ennobled in this way after making monetary donations. These are informally known as letter nobility (Norwegian: brevadel).

One of the earliest known letters patent is from 1458, given to Sjøfar and Nils Sigurdssøner by King Eric III. Other families are Rosenvinge and Tordenstjerne, both ennobled in 1505. However, the custom of ennobling by letters patent increased drastically in the late 17th century and the 18th century, when innumerous persons and families received such noble status. They were a part of the King's plan of creating a new and loyal nobility replacing the old, who until 1660 had been political enemies of the King. However, letters patent given (unofficially: sold) among others to rich merchants were also a lucrative source of income for the Kings, whose many wars at times lead to a big need for money.

Examples:

- Kurt Sørensen was for bravery in battle ennobled under the name Adeler.

- Ludvig Holberg, a famous writer, was ennobled as a baron for his merits and by bequeathing his fortune to the Sorø Academy.

- Joachim Geelmuyden, the son of a priest and the grandson of a tradesman, held many titles and offices in the Dano-Norwegian state and was subsequently ennobled under the name Gyldenkrantz.

Feudal nobility

Photographer: Nynorsk Wikipedia user Ekko

With feudal barons and feudal counts one saw the introduction of a neo-feudal structure in Norway. These modern fiefs were ruled with conditioned independence by noble familie, and they were hereditable. Feudal lords were equipped with extensive rights and duties. On the other hand, a fief was formally a dominium directum of the King. It would as such return to the Crown when a title became extinct (see for example Barony of Rosendal) or when a feudal lord was sentenced for illoyality (see for example Countship of Griffenfeld).

The main architect behind the new system of barons and counts, introduced in 1671, was Peder Schumacher, who himself was ennobled as Peder Schumacher Griffenfeld in 1671 and created Count of Griffenfeld in 1673. In 1675 the citizens of Tønsberg lost their independence, and the city was merged into the Countship. Griffenfeld had been granted the sole right to all mining and hunting within the Countship. He could appoint judges, arrest and charge inhabitants, and punish sentenced criminals. He could appoint priests to all churches, which he owned. Several duties were imposed on the Count's subjects. For example, cotters (Norwegian: husmann) under the Count had to work for him without payment.

Whilst these new politics could bring fundamental changes to each area concerned, the effect and the consequences remained limited in Norway in general, as originally only two countships and one barony were created. These included only a small amount of the Norwegian population. Divided into counties (Norwegian: amt), the rest of Norway was under direct royal administration.

Huguenot immigration

Lutheran Evangelical kingdoms, Denmark and Norway welcomed Huguenots who had escaped from France following the 1685 revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Huguenots were greeted with several privileges, and some even achieved noble status and/or titles. One was Jean Henri Huguetan (1665–1749) from Lyon, who was created Count of Gyldensteen in 1717.

Increasing influence of Norwegians

During the 18th century, Norwegian-born noblemen and burghers rose to prominence within the Dano-Norwegian state.

Introduction of the stavnsbånd

In 1733 King Christian VI introduced the system of stavnsbånd—a serfdom-like institution—in Denmark. This was introduced following an agricultural crisis that lead people to leave the countryside and move into towns. The system would last until after 1788.

The stavnsbånd was not introduced in Norway, where all men had been free since the Old Norse heathen trelldom was fought and abolished by the Roman Catholic Church.

Years of Struensee

Artist: unknown

During the de facto reign of Johann Friedrich Struensee between 1770 and 1772 the power of the nobility in Denmark and Norway was challenged. Whilst he did not mind creating himself and his friend Brandt feudal counts, Struensee was an enemy of the hereditary aristocracy, which he sought to replace with a merit-based system of government. A part of his reforms Struensee abolished noble privileges and decided that state employments should be based on a person's qualifications only.

In a counter-coup on 17 January 1772 Ove Høegh-Guldberg, Hans Henrik von Eickstedt, Georg Ludwig von Köller-Banner and others had Struensee arrested. In a following trial he was sentenced to death. On 28 April ex-counts Brandt and Struensee were executed; first their right hands were cut off, whereafter they were beheaded and had their bodies drawn and quartered.

1814 Constitution and 1821 Nobility Law

The Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway of 1814, which had been established in the spirit of the principles of the French Revolution and greatly influenced by the Constitution of the United States of America, forbade the creation of new nobility, including countships, baronies, family estates (Norwegian: stamhus), and fee tails (Norwegian: fideikommiss). Beside being in accordance with the contemporary political ideology, the prohibition effectively removed the possibility for Norway’s king, who after 1814 also was Sweden’s king, to create a nobility of Swedes and loyal Norwegians.

The Nobility Law of 1821 (Norwegian: Adelsloven) initiated a long-range abolition of all noble titles and privileges, while the current nobility were allowed to keep their noble status, possible titles and in some cases also privileges for the rest of their lifetime. Under the Nobility Law, nobles who for themselves and their children wished to present a claim to nobility before the Norwegian parliament were required to provide documentation confirming their noble status. Representatives of eighteen noble families submitted their claims to the Parliament.[48]

In 1815 and in 1818, the Parliament had passed the same law, and it was both times vetoed by the King.[49] The King did not possess a third veto, so he had to approve the law in 1821. Shortly afterwards, the King suggested the creation of a new nobility, but the attempt was rejected by the Parliament.[50]

Many of the Norwegians who had noble status in Norway had noble status also in Denmark and thus remained noble. This and the fact that many Norwegian nobles did not live in the country may have contributed to reduced resistance to the Nobility Law. However, there was resistance, which found its most significant expression in Severin Løvenskiold, who had fought against the democracy and who worked for stopping the Nobility Law.[51] Being an important politician and an allied of the King, Løvenskiold was not without power. Løvenskiold argued against the law that Norway’s king, and thus the Kingdom’s government, had granted his family eternal noble status, and the letters patent of 1739 uses the expression ‘eternally’.[52][53] At the same time, the Constitution’s § 97 in fact stated: ‘No law must be given retroactive force.’[54]

The last Norwegian count with official recognition was Peder Anker, Count of Wedel-Jarlsberg, who died in 1893. His younger brothers were Herman, Baron of Wedel-Jarlsberg, who died in 1888, and Harald, Baron of Wedel-Jarlsberg, who died in 1897. The cousins Ulriche Antoinette de Schouboe (1813–1901) and Julie Elise de Schouboe (1813–1911), as well as Anne Sophie Dorothea Knagenhjelm (1821–1907), died early in the 20th century as some of Norway’s last persons who had had official recognition as noble.

Although the institution of nobility gradually was dissolved, members of noble families continued to play a significant rôle in the political and social life of the country. For example, Stewards and Prime Ministers such as Count Herman Wedel-Jarlsberg (Steward, 1836–1840), Severin Løvenskiold (Steward, 1841–1856, Prime Minister, 1828–1841), Peder Anker (Prime Minister, 1814–1822), Frederik Due (Prime Minister, 1841–1858), Georg Sibbern (Prime Minister, 1858–1871) and Carl Otto Løvenskiold (Prime Minister, 1884) had aristocratic backgrounds.

1905 Independence

Aristocrats were active also in the dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden in 1905. Most prominent were diplomat Fritz Wedel Jarlsberg and world-famous polar explorer Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen. Nansen, who otherwise became Norway’s first ambassador to London (1906–08), was pro dissolving the union and, among other acts, travelled to the United Kingdom, where he successfully lobbied for support for the independence movement. Also in the ensuing referendum concerning monarchy versus republic in Norway, the popular hero Nansen’s support of monarchy and his active participation in the pro-monarchy campaign is said to have had an important effect on popular opinion. After the dissolution of the union, the leading person in the creation of the new state’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was Thor von Ditten, a Norwegian of foreign nobility.

Nationalism and German occupation

_inspiserer_Rikshirden.jpg)

In the 1920s and 1930s, Norway experienced an increasing and more political nationalism. Among other things, this led to the creation of the national socialist party National Unification in 1933. Inspired by medieval aristocracy and Viking society and ideals, the National Unification established the paramilitary organisation The Hird. Established to protect the party and its leader, Vidkun Quisling, it had obvious parallels to the medieval aristocratic class hird, who were lifeguards of the King.

Likewise, in 1940, during the German occupation of Norway (1940–1945), attempts were made to introduce a new government called Riksrådet (lit. The Council of the Realm). In medieval Norway, Riksrådet was the name of the Kingdom's government, which was also an institution controlled by and restricted to aristocrats.

It is not random that medieval ages and their institutions were idolised. Modern aristocracy was strongly associated with foreignness, more specifically with Denmark and the Dano-Norwegian union (1524–1814). Medieval aristocracy, however, satisfied nationalists' desire for ('true', 'pure') Norwegianness. The search for genuine Norwegianness was, however, a general trait of Norwegian romantic nationalism. A young and small nation sought pride in its mighty history.

Present state

Today, the nobility is a relatively marginal factor in the society, culturally and socially as well as in politics. Members of noble families are only individually prominent, like Anniken Huitfeldt. However, a handful of families, like Løvenskiold, Treschow, and Wedel-Jarlsberg, still possess considerable wealth. This includes fame and regular appearance in newspapers and also coloured magazines.

Landowner and businessman Carl Otto Løvenskiold owns Maxbo among other companies. The brothers Nicolai and Peder Løvenskiold own a large number of higher private schools in Norway, among others the Westerdals School of Communication, the Bjørknes College, and the Norwegian School of Information Technology.[55] Prominent is also landowner and businesswoman Mille-Marie Treschow, who is one of the wealthiest women in Norway.

Until and during the 20th century noble persons have served at the Royal Court in Oslo. Prominent are (since 1985) Mistress of the Robes Ingegjerd Løvenskiold Stuart and (between 1931 and 1945) Lord Chamberlain Peder Anker Wedel-Jarlsberg.

The Knagenhjelm family is by many associated with WW2 resistance hero Nils Knagenhjelm (1920–2004).[56]

Although privileges were abolished and official recognition of titles was removed, some families still consider themselves noble by tradition and—lawfully—still bear their inherited name and coat of arms. Claims to nobility have no effect or support in law. There are still Norwegians who enjoy official recognition from the Danish government;—the nobility in Denmark still exists. They are likewise included in the Yearbook of the Danish Nobility, published by the Association of the Danish Nobility.

The family Roos af Hjelmsäter of the Swedish nobility is among the disappearingly few of Norway's medieval noble families still living today.[57]

Noble influence and legacy

Photographer: Commons user Bjoertvedt

Photographer: Helge Høifødt

The aristocracy has ruled and shaped Norway during nearly the whole existence of the Kingdom. Products of and references to the aristocracy are both visible and less explicit in today′s society.

Major cases

In 1814 noblemen were leading when a constitutional monarchy and a parliament were established in Norway. Among them were the Count of Wedel-Jarlsberg, Peder Anker, and Christian Magnus Falsen. The Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway of 1814, which is still in function, was written by a nobleman, namely by Falsen. This constitution grants, among other things, freedom of speech, protection of private property, and prohibition of painful search and seizure.

In 1905 members of the aristocracy were leading in the independence movement. Eystein Eggen has claimed Norway's independence was realised by a 'genuinely aristocratic wave',[59][60] in which especially Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen and Fritz Wedel-Jarlsberg were important persons.

References

- In culture

- Christian Magnus Falsen was depicted on the 1,000 kroner bank-note between 1979 and 2001.

- Peter Wessel Tordenskiold was together with non-noble Wilhelm Frimann Koren Christie depicted on the 1,000 kroner bank-note, the 100 kroner bank-note, and the 10 kroner bank-note between 1901 and 1945.

- The idiom Tordenskiold's soldiers (Norwegian: Tordenskiolds soldater) is related to aforementioned Tordenskiold.[61]

- Lady Inger of Ostrat is a famous romantic nationalist play published by Henrik Ibsen in 1857. It refers to Lady Ingerd Ottesdotter Rømer to Austrått. Based on the play a movie was made in 1975 by Sverre Udnæs.[62]

- Some official coats of arms display or are inspired by noble coats of arms, among others those of the municipalities Sarpsborg (see Alv Erlingsson) and Våler (see Bolt) and of the county Troms (see Bjarkøy dynasty). The coat of arms of Lillehammer displays a Birchleg. KNM Tordenskjold, the Royal Norwegian Navy′s school for maritime warfare, uses aforementioned Tordenskiold's arms.

- The Werenskiold family have produced two prominent artists, namely Erik Werenskiold (1855–1938), who especially is known for his illustrations of Norse sagas, and his son Dagfin Werenskiold (1892–1977), a sculptor and a painter.

- In names and places

- Several streets, squares and so on are named after noblemen, among others Grev Wedels plass (Count Wedel Square), Løvenskiolds gate (Løvenskiold Street), Majorstua (a part of Oslo), and Wedel Jarlsberg Land.

- Several buildings, enterprises and so on are named after noblemen, among others Best Western Gyldenløve Hotell (a hotel), Marie Treschow (a private home for old people), and Georg Morgenstiernes Hus (a building at the University of Oslo campus).

- Philanthropy

Norwegian foundations origined along with settled estates (stamhus) and fee tails (fideikommiss) during absolutism in Norway, and noblemen were among the first to establish such. In 1814, when the Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway was introduced, the foundation system was the only to survive; the creation of new settled estates and new fee tails was prohibited.

Of over 7,000 foundations in Norway today, several have been established by or bear the name of noble persons and families. An example is the Comital Foundation of Hielmstierne-Rosencrone,[63] providing financial support to certain poor women in Bergen. Others are:

- Det Ankerske Broderbørns og Descendenters Midler (Anker family)[64]

- Stiftelsen Det Ankerske Waisenhus (Anker family)[64]

- Eva og Erik Ankers Legat (Anker family)[64]

- Johan Ankers Fond (Anker family)[64]

- Stiftelsen De Ankerske Samlinger (Anker family)[64]

- Assessor L.W. Knagenhjelm og Fru Selma f. Rolls Legat (Knagenhjelm family)[64]

- Otto Løvenskiolds Legat (Løvenskiold family)[64]

- Statsminister Carl Løvenskiold og Frues Legat (Løvenskiold family)[64]

- Legatet til Otto Løvenskiolds Minde (Løvenskiold family)[64]

- Professor Morgenstiernes Fond (Munthe af Morgenstierne family, B.H. von M. af M.)[64]

- Den Grevelige Hielmstierne Rosencroneske Stiftelse (Count and Countess of Rosencrone)[64]

- Den Grevelige Hjelmstjerne-Rosencroneske Stiftelse ved Universitetet i Oslo (Count and Countess of Rosencrone)[64]

- Den Grevelige Hjelmstjerne-Rosencroneske Stiftelse til Universitetsbiblioteket i Oslo (Count and Countess of Rosencrone)[64]

- Den Grevelige Hielmstierne Rosencroneske Stiftelses Legat v/Det Kgl. Norske Videnskabers Selskabs Stiftelse (Count and Countess of Rosencrone)[64]

- Stiftelsen Skoleskibet Tordenskiold (P.W. Tordenskiold)[64]

- Trampes Legat (Countess of Trampe)[64]

- Fritz Gerhard Treschows Minnefond (Treschow family)[64]

- Willum Frederik Treschows Handelhøyskolefond (Treschow family)[64]

- Wedel-Jarlsbergsfond (Counts of Jarlsberg)[64]

- Familien Wedel Jarlsbergs Stiftelse til Fordel for Jarlsberg Hovedgårds Pensjonister (Counts of Jarlsberg)[64]

- Frk Harriet Wedel-Jarlsbergs Pensjonsfond for Bærums Verk (Counts of Jarlsberg)[64]

- Gustav og Maria Smith og Hermann Wedel-Jarlsbergs Legat (Counts of Jarlsberg)[64]

- Jarlsberg Hovedgårds Gravstedlegat (Counts of Jarlsberg)[64]

- Wollstonecraft

In her work Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, published in 1796, Mary Wollstonecraft shares her impressions of Norway. Some descriptions are related to the nobility and to the social structure:[65]

- 'Though the king of Denmark be an absolute monarch, yet the Norwegians appear to enjoy all the blessings of freedom. Norway may be termed a sister kingdom; but the people have no viceroy to lord it over them, [...]' Letter VII.

- '[...] the Norwegians appear to me to be the most free community I have ever observed.' Letter VII.

- 'There are only two counts in the whole country who have estates, and exact some feudal observances from their tenantry.' Letter VII.

- 'In short, I have seldom heard of any noblemen so innoxious.' Letter IX.

- '[In Christiania, i.e. Oslo,] I saw the cloven foot of despotism. I boasted to you that they had no viceroy in Norway, but these Grand Bailiffs, particularly the superior one, who resides at Christiania, are political monsters of the same species. [...] The Grand Bailiffs are mostly noblemen from Copenhagen, [...]' Letter XIII.

- 'The aristocracy in Norway, if we keep clear of Christiania, is far from being formidable; and it will require a long the to enable the merchants to attain a sufficient moneyed interest to induce them to reinforce the upper class at the expense of the yeomanry, with whom they are usually connected.' Letter XIV.

Noble families

Ancient aristocratic families

The following list contains families who appeared before, during, and after the so-called unification of Norway (c. 872–1050). To these belonged also the post-unification lendman aristocracy (1050–1184/1240).

| Name | Appearance | Extinction | Information | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnmødling Dynasty | 10th century[13] | Appears with Earl Arnmod, who died in the Battle of Hjörungavágr. | [13] | |

| Bjarkøy Dynasty, the older line | 10th century | Appears with Þórir hundr Þórirsson. | [66] | |

| Bjarkøy Dynasty, the younger line | 1355[66] | Established with Jon Arnason of the Arnmødlings, who married Þórir hundr's granddaughter Rannveig Þórirsdóttir.[66] | ||

| Giske Dynasty | 11th century | 1265[16] | Established with Torberg Arnason of the Arnmødlings. | [16] |

| Rein Dynasty | Appears with Skuli Tostisson, an alleged son of Tostig Godwinson, Earl of Northumbria. | [67] | ||

| Sudreim Dynasty | 12th century | Alive. | Appears with Lendman Åle varg Ivarsson. Still alive as the Roos af Hjelmsäter family. | [14] |

| Tornberg Dynasty | 12th century | 1290[68] | [68] |

Medieval aristocratic families

The following list contains families who appeared as noble or who were ennobled between 1184 and 1537.

| C.o.a. | Name | Classification | Ennoblement | Denoblement | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akeleye | |||||

| Aspa | ||||||

| Bagge | ||||||

| Benkestok | Squire Knight Riksråd nobility | ||||

| von Bergen | Riksråd | Riksråd (Anders von Bergen, 1489) | ||||

| Bildt | ||||||

| Bjelke | 15th century | 1868 by extinction | |||

| Bonde | ||||||

| Blix | ||||||

| Biskopsson, Biskop-ætten | Baron

Chancellor Riksråd |

|||||

| Bolt | Riksråd | |||||

| Bratt | ||||||

| Budde | ||||||

| Båt | ||||||

| Darre | ||||||

| Galle, Galde | Riksråd | |||||

| Galte | |||||

| Gerst | Knight

Riksråd |

|||||

| Gjedde | |||||

| Gjæsling | Riksråd | |||||

| Green af Rossø | ||||||

| Green af Sundsby | Chancellor of Norway | |||||

_COA.jpg) | Gyldenløve |

Knight Riksård Steward of the Realm |

||||

| Güntersberg | Immigrate to Norway in 1520 | |||||

| Holk | Riksråd

Kansler |

|||||

| Hummer | 1532 by letter | |||||

| Hård | ||||||

| Jernskjegg | ||||||

| Kamp | ||||||

| | Kane | Squire Knight Riksråd nobility | ||||

| Krabbe | ||||||

| Kruckow | ||||||

| Kusse | ||||||

| Losna Family, the older line | Fehirde[69] Riksråd nobility[69] | 13th century[70] | 1452 (c.) by extinction [69] | [69] | |

| Losna Family, the younger line | Knight[71] Riksråd nobility[71] | 1450s | 1526[71] by extinction (main lineage) | |||

| Norbagge | Noble | 1488 by letter | [72] | |||

| Rogne | Rømer | |||||

| Sinclair | Riksråd | 1321 inherit the earldom | ||||

| Skanke | Knight | ||||

| Smør | Knight Riksråd nobility Regent of Norway | ||||

| Staur | 1527 by letter | |||||

| Stjerne | Knight Riksråd nobility Regent of Norway | |||||

| Teiste | ||||||

| Tordenstjerne | Noble Squire | 1505 by letter | 18th century by extinction |

Medieval aristocratic families of foreign origin

The following list contains (1) Danish and Swedish noble families who immigrated to Norway before 1660 and (2) foreign noble families who immigrated to and received naturalisation in Norway before 1660.

| C.o.a. | Name | Classification | Immigration and/or naturalisation | Country of origin | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bille | ||||

| Gyldenstierne | |||||

| Huitfeldt | ||||

| Juel/Iuel | |||||

| Kaas | ||||

| Mowat | Noble | Scotland | |||

| Norman de la Navité | Noble | France | |||

| Rosenkrantz | Noble | Denmark |

Modern aristocratic families

The following list contains (1) Norwegians who were ennobled in Norway between 1537 and 1660 and (2) Norwegians and Danes who were ennobled in Norway or in Denmark between 1660 and 1814. This list may not contain Danes who were ennobled in Denmark before 1660.

Years of denoblement (extinction) refer to when the last noble male member died. It should, however, be noted that several letters patent treated men and women equally; when unmarried or widowed, such women had a personal and independent status as noble. An example is the letters patent of the Løvenskiold family, which uses the term 'legitimate issue of the male and the female sexus'.[73]

- Marquises

| C.o.a. | Name of title | Name of receiver | Sexus | Name of inheriting family | Creation | Abolishment | Country of location | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marquisate of Lista | Hugo Octavius Accoramboni (Italian) | M | No inheritors. | 1709 | Norway | |||

| Marquisate of Mandal | Francisco di Ratta (Italian) Giuseppe di Ratta (Italian) Luigi di Ratta (Italian) | M M M | di Ratta | 1710 | 1821 (Norway) 1890 (Denmark) | Norway | [74] | |

- Feudal counts

| C.o.a. | Name of fief | P. | Name of receiver | Sexus | Name of inheriting family | Erection | Dissolution | Country of location | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countship of Arntvorskov |  | Elisabeth Helene von Vieregg | F | 1703 | Denmark | ||||

| | Countship of Brahesminde |  | Preben Bille-Brahe | M | Bille-Brahe | 1798 | Denmark | ||

| Countship of Brandt |  | Enevold Brandt | M | 1771 | 1772 | Denmark | |||