Progestogen

Progestogens, also sometimes spelled progestagens or gestagens,[1] are a class of steroid hormones that bind to and activate the progesterone receptor (PR).[2][3] Progesterone is the major and most important progestogen in the body, while progestins are synthetic progestogens.[2] Major examples of progestins include the 17α-hydroxyprogesterone derivative medroxyprogesterone acetate and the 19-nortestosterone derivative norethisterone (norethindrone). The progestogens are named for their function in maintaining pregnancy (i.e., progestational), although they are also present at other phases of the estrous and menstrual cycles.[2][3]

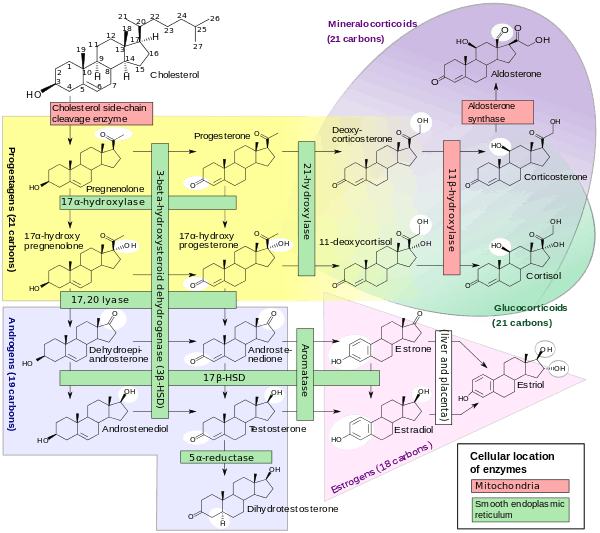

The progestogens are one of the five major classes of steroid hormones, in addition to the androgens, estrogens, glucocorticoids, and mineralocorticoids, as well as the neurosteroids. All progestogens are characterized by their basic 21-carbon skeleton, called a pregnane skeleton (C21). In similar manner, the estrogens possess an estrane skeleton (C18), and androgens, an androstane skeleton (C19).

The terms progesterone, progestogen, and progestin are mistakenly used interchangeably both in the scientific literature and in clinical settings.[1][4][5] While the progestins are structural analogues of progesterone, they are not functional analogues, and differ from progesterone considerably in their properties.[5]

Types

The most important progestogen in the body is progesterone (P4). Other endogenous progestogens include 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, 20α-dihydroprogesterone, 5α-dihydroprogesterone, 11-deoxycorticosterone, and 5α-dihydrodeoxycorticosterone.

Biological function

In the first step in the steroidogenic pathway, cholesterol is converted into pregnenolone (P5), which serves as the precursor to the progestogens progesterone and 17α-hydroxyprogesterone. These progestogens, along with another steroid, 17α-hydroxypregnenolone, are the precursors of all other endogenous steroids, including the androgens, estrogens, glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, and neurosteroids. Thus, many tissues producing steroids, including the adrenal glands, testes, and ovaries, produce progestogens.

In some tissues, the enzymes required for the final product are not all located in a single cell. For example, in ovarian follicles, cholesterol is converted to androstenedione, an androgen, in the theca cells, which is then further converted into estrogen in the granulosa cells. Fetal adrenal glands also produce pregnenolone in some species, which is converted into progesterone and estrogens by the placenta (see below). In the human, the fetal adrenals produce dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) via the pregnenolone pathway.

Ovarian production

Progesterone is the major progestogen produced by the corpus luteum of the ovary in all mammalian species. Luteal cells possess the necessary enzymes to convert cholesterol to pregnenolone, which is subsequently converted into progesterone. Progesterone is highest in the diestrus phase of the estrous cycle.

Placental production

The role of the placenta in progestogen production varies by species. In the sheep, horse, and human, the placenta takes over the majority of progestogen production, whereas in other species the corpus luteum remains the primary source of progestogens. In the sheep and human, progesterone is the major placental progestogen.

The equine placenta produces a variety of progestogens, primarily 5α-dihydroprogesterone and 5α,20α-tetrahydroprogesterone, beginning on day 60. A complete luteo-placental shift occurs by day 120–150.

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis

Progesterone is produced from cholesterol with pregnenolone as a metabolic intermediate.

See also

References

- 1 2 Tekoa L. King; Mary C. Brucker (25 October 2010). Pharmacology for Women's Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 373. ISBN 978-1-4496-5800-7.

- 1 2 3 Michelle A. Clark; Richard A. Harvey; Richard Finkel; Jose A. Rey; Karen Whalen (15 December 2011). Pharmacology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-4511-1314-3.

- 1 2 Bhattacharya (1 January 2003). Pharmacology, 2/e. Elsevier India. p. 378. ISBN 978-81-8147-009-6.

- ↑ Tara Parker-Pope (25 March 2008). The Hormone Decision. Simon and Schuster. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-4165-6201-6.

- 1 2 Grant, Ellen (1994). Sexual chemistry: understanding your hormones, the Pill and HRT. Great Britain: Cedar. p. 39. ISBN 0749313633.

- ↑ Häggström, Mikael; Richfield, David (2014). "Diagram of the pathways of human steroidogenesis". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.005. ISSN 2002-4436.

Further reading

- Utian WH, Shoupe D, Bachmann G, Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH (June 2001). "Relief of vasomotor symptoms and vaginal atrophy with lower doses of conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate". Fertil. Steril. 75 (6): 1065–79. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(01)01791-5. PMID 11384629. (the Women's Health, Osteoporosis, Progestin, Estrogen study)

- Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. (August 1998). "Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group". JAMA. 280 (7): 605–13. doi:10.1001/jama.280.7.605. PMID 9718051.

External links

- Progestins at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- The Nomenclature of Steroids

- The Million Women Study