Open front unrounded vowel

| Open front unrounded vowel | |

|---|---|

| a | |

| a̟ | |

| æ̞ | |

| IPA number | 304 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) |

a |

| Unicode (hex) | U+0061 |

| X-SAMPA |

a or a_+ or {_o |

| Kirshenbaum |

a |

| Braille |

|

| Sound | |

|

source · help | |

The open front unrounded vowel, or low front unrounded vowel, is a type of vowel sound, used in some spoken languages. It is one of the eight primary cardinal vowels, not directly intended to correspond to a vowel sound of a specific language but rather to serve as a fundamental reference point in a phonetic measuring system.[1]

The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) that represents this sound is ⟨a⟩, and in the IPA vowel chart it is positioned at the lower-left corner. However, the accuracy of the quadrilateral vowel chart is disputed, and the sound has been analyzed acoustically as an extra-open/low unrounded central vowel at a position where the front/back distinction has lost its significance. There are also differing interpretations of the exact quality of the vowel: the classic sound recording of [a] by Daniel Jones is slightly more front but not quite as open as that by John Wells.[2]

In practice, it is considered normal by many phoneticians to use the symbol ⟨a⟩ for an open central unrounded vowel and instead approximate the open front unrounded vowel with ⟨æ⟩ (which officially signifies a near-open front unrounded vowel).[3] This is the usual practice, for example, in the historical study of the English language. The loss of separate symbols for open and near-open front vowels is usually considered unproblematic, because the perceptual difference between the two is quite small, and very few languages contrast the two. If one needs to specify that the vowel is front, they can use symbols like ⟨a̟⟩ (advanced [a]), or ⟨æ̞⟩ (lowered [æ]), with the latter being more common.

The Hamont dialect of Limburgish has been reported to contrast long open front, central and back unrounded vowels,[4] which is extremely unusual.

Features

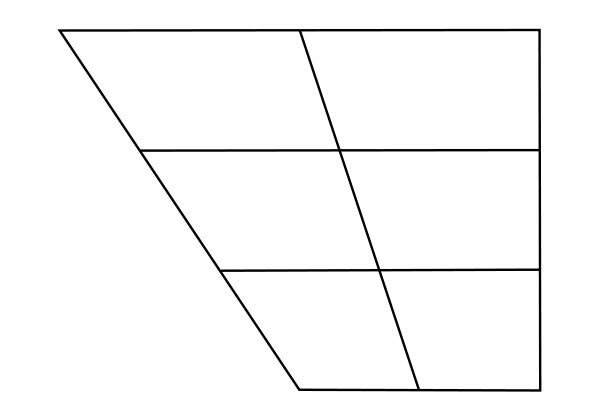

| IPA vowel chart | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Paired vowels are: unrounded • rounded | |||||||||||||||||||

| This table contains phonetic symbols, which may not display correctly in some browsers. [Help] | |||||||||||||||||||

|

IPA help • IPA key • chart • | |||||||||||||||||||

- Its vowel height is open, also known as low, which means the tongue is positioned as far as possible from the roof of the mouth – that is, as low as possible in the mouth.

- Its vowel backness is front, which means the tongue is positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Note that rounded front vowels are often centralized, which means that often they are in fact near-front. This subsumes central open (central low) vowels because the tongue does not have as much flexibility in positioning as it does in the mid and close (high) vowels; the difference between an open front vowel and an open back vowel is similar to the difference between a close front and a close central vowel, or a close central and a close back vowel.

- It is unrounded, which means that the lips are not rounded.

Occurrence

Many languages have some form of an unrounded open vowel. For languages that have only a single open vowel, the symbol for this vowel ⟨a⟩ may be used because it is the only open vowel whose symbol is part of the basic Latin alphabet. Whenever marked as such, the vowel is closer to a central [ä] than to a front [a].

| Language | Word | IPA | Meaning | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic | Standard[5] | أنا | [anaː] | 'I am' | See Arabic phonology | |

| Assamese | আম | [am] | 'mango' | |||

| Assyrian Neo-Aramaic | la | [laː] | 'no' | Widely present in Urmia and Jilu dialects. Corresponds to [ä] in most of the other varieties. In the Tyari dialect, [ɑ] is usually used. | ||

| Bulgarian[6] | най | [n̪a̠j] | 'most' | Near-front.[6] | ||

| Catalan | Many dialects | llamp | [ˈl̠ʲæ̞m(p)] | 'lightning' | Allophone of /a/ in contact with palatal consonants. It may vary between /ɛ/ and /a/. See Catalan phonology | |

| Majorcan | sac | [ˈsæ̞k] | 'sack' | Fully front and slightly closed | ||

| Valencian | Usually more centralized. It alternates with ⟨ɐ⟩ (i.e. [ä̝], [ɑ̝̈] and [ɛ̞̈] ~ [ɔ̞̈]) during vowel harmony processes. | |||||

| Chinese | Mandarin | 安/ān | | 'safe' | Allophone of /a/ before /i, n/ when not preceded by a palatal. See Standard Chinese phonology | |

| Danish | Some speakers[7] | Dansk | [ˈd̥ansɡ̊] | 'Danish' | Used by certain older or upper-class speakers; it corresponds to near-open [æ] in contemporary Standard Danish.[8] See Danish phonology | |

| Dutch | Standard[9] | aas | [aːs] | 'bait' | Ranges from front to central.[10] See Dutch phonology | |

| Groningen[11] | ||||||

| Broad Amsterdam[12] | ijs | 'ice' | Corresponds to [ɛi̯] in Standard Dutch. See Dutch phonology | |||

| Utrecht[13] | bad | [bat] | 'bath' | Corresponds to [ɑ] in Standard Netherlandic Dutch. See Dutch phonology | ||

| English | California[14][15] | hat | | 'hat' | In other accents, or in some other speakers of the accents listed here, the quality may be anywhere from front [ɛ ~ æ ~ a] to central [ä] to back [ɑ], depending on the region. In some regions, the quality may be variable. For the Canadian vowel, see Canadian Shift. See also English phonology | |

| Canadian[15][16] | ||||||

| Few younger speakers from Texas[15] | ||||||

| Many younger Australian speakers[17] | ||||||

| Modern speakers of Received Pronunciation[18] | ||||||

| Northern Suburbs of Johannesburg[19] | ||||||

| Some speakers from central Ohio[15] | ||||||

| Cockney[20][21] | stuck | [stak] | 'stuck' | Can be [ɐ̟] instead. | ||

| Inland Northern American[22] | stock | 'stock' | Less front [ɑ ~ ä] in other American dialects. See Northern cities vowel shift | |||

| French | Conservative Parisian[23] | patte | [pat̪] | 'paw' | Contrasts with [ɑ], but many speakers have only one open vowel [ä]. See French phonology | |

| Galician[24] | caixa | [ˈkajʃä] | 'box' | Allophone of /a/ before palatal consonants.[24] See Galician phonology | ||

| German | Bernese | drääje | [ˈtræ̞ːjə] | 'turn' | See Bernese German phonology | |

| Gujarati | શાંતિ/shanti | [ʃant̪i] | 'peace' | See Gujarati phonology | ||

| Igbo[25] | ákụ | [ákú̙] | 'kernal' | |||

| Kabardian | дахэ | | 'pretty' | |||

| Limburgish[4][26][27][28] | baas | [baːs] | 'boss' | Front or near-front, depending on the dialect.[4][26][27][28] The example word is from the Maastrichtian dialect.[27] | ||

| Luxembourgish[29][30] | Kap | [kʰaːpʰ] | 'cap' | Described variously as front[29] and near-front.[30] See Luxembourgish phonology | ||

| North Frisian | braan | [braːn] | 'to burn' | |||

| Norwegian | Stavangersk[31] | hatt | [hat] | 'hat' | See Norwegian phonology | |

| Trondheimsk[32] | lær | [laːɾ] | 'leather' | |||

| West Farsund[33] | hat | [haːt] | 'hate' | Some speakers, for others it is more back. See Norwegian phonology | ||

| Polish[34] | jajo | | 'egg' | Allophone of /a/ between palatal or palatalized consonants. See Polish phonology | ||

| Portuguese | Most Brazilian dialects | informática | [ĩfɔ̞χˈmat͡ʃjkɐ] | 'computing' | See Portuguese phonology | |

| Slovak[35] | a | [a̠] | 'and' | Near-front; possible realization of /a/. Most commonly realized as central [ä] instead.[36] See Slovak phonology | ||

| Spanish | Eastern Andalusian[37] | las madres | [læ̞ˑ ˈmæ̞ːð̞ɾɛˑ] | 'the mothers' | Corresponds to [ä] in other dialects, but in these dialects they're distinct. See Spanish phonology | |

| Murcian[37] | ||||||

| Swedish | Central Standard[38] | bank | [baŋk] | 'bank' | Also described as central [ä].[39] See Swedish phonology | |

| Vastese[40] | ||||||

| Welsh | mam | [mam] | 'mother' | See Welsh phonology | ||

| Zapotec | Tilquiapan[41] | na | [na] | 'now' | ||

References

- ↑ John Coleman: Cardinal vowels

- ↑ Geoff Lindsey (2013) The vowel space, Speech Talk

- ↑ Keith Johnson: Vowels in the languages of the world (PDF), p. 9

- 1 2 3 Verhoeven (2007), p. 221.

- ↑ Thelwall & Sa'Adeddin (1990), p. 38.

- 1 2 Ternes & Vladimirova-Buhtz (1999), p. 56.

- ↑ Basbøll (2005:32)

- ↑ Basbøll (2005:32, 45)

- ↑ Collins & Mees (2003), pp. 95, 104, 132-133.

- ↑ Collins & Mees (2003), p. 104.

- ↑ Collins & Mees (2003), p. 133.

- ↑ Collins & Mees (2003), p. 136.

- ↑ Collins & Mees (2003), p. 131.

- ↑ Gordon (2004), p. 347.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas (2004:308): A few younger speakers from, e.g., Texas, who show the LOT/THOUGHT merger have TRAP shifted toward [a], but this retraction is not yet as common as in some non-Southern regions (e.g., California and Canada), though it is increasing in parts of the Midwest on the margins of the South (e.g., central Ohio).

- ↑ Boberg (2005), pp. 133–154.

- ↑ Cox (2012), p. 160.

- ↑ "Case Studies – Received Pronunciation Phonology – RP Vowel Sounds". British Library.

- ↑ Bekker (2008), pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Wells (1982), p. 305.

- ↑ Hughes & Trudgill (1979), p. 35.

- ↑ W. Labov, S. Ash and C. Boberg (1997). "A national map of the regional dialects of American English". Department of Linguistics, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ↑ Ashby (2011), p. 100.

- 1 2 Freixeiro Mato (2006), pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Ikekeonwu (1999), p. 109.

- 1 2 Peters (2006), p. 119.

- 1 2 3 Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), p. 159.

- 1 2 Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), p. 110.

- 1 2 Trouvain & Gilles (2009), p. 75.

- 1 2 Gilles & Trouvain (2013), p. 70.

- ↑ Vanvik (1979), p. 17.

- ↑ Vanvik (1979), p. 15.

- ↑ Vanvik (1979), p. 16.

- ↑ Jassem (2003), p. 106.

- ↑ Pavlík (2004:95)

- ↑ Pavlík (2004:94–95)

- 1 2 Zamora Vicente (1967), p. ?.

- ↑ Thorén & Petterson (1992), p. 15.

- ↑ Engstrand (1999), p. 140.

- ↑ "Vastesi Language - Vastesi in the World". Vastesi in the World. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ Merrill (2008), p. 109.

Bibliography

- Ashby, Patricia (2011), Understanding Phonetics, Understanding Language series, Routledge, ISBN 978-0340928271

- Basbøll, Hans (2005), The Phonology of Danish, ISBN 0-203-97876-5

- Bekker, Ian (2008). The vowels of South African English (PDF) (Ph.D.). North-West University, Potchefstroom.

- Boberg, Charles (2005), "The Canadian shift in Montreal", Language Variation and Change, 17: 133–154, doi:10.1017/s0954394505050064

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2003), The Phonetics of English and Dutch, Fifth Revised Edition (PDF), ISBN 9004103406

- Cox, Felicity (2012), Australian English Pronunciation and Transcription, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-14589-3

- Freixeiro Mato, Xosé Ramón (2006), Gramática da lingua galega (I). Fonética e fonoloxía (in Galician), Vigo: A Nosa Terra, ISBN 978-84-8341-060-8

- Gilles, Peter; Trouvain, Jürgen (2013), "Luxembourgish" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43 (1): 67–74, doi:10.1017/S0025100312000278

- Gordon, Matthew J. (2004), "The West and Midwest: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 338–351, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Gussenhoven, Carlos; Aarts, Flor (1999), "The dialect of Maastricht" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, University of Nijmegen, Centre for Language Studies, 29: 155–166, doi:10.1017/S0025100300006526

- Heijmans, Linda; Gussenhoven, Carlos (1998), "The Dutch dialect of Weert" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 28: 107–112, doi:10.1017/S0025100300006307

- Hughes, Arthur; Trudgill, Peter (1979), English Accents and Dialects: An Introduction to Social and Regional Varieties of British English, Baltimore: University Park Press

- Ikekeonwu, Clara (1999), "Igbo", Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, pp. 108–110, ISBN 0-521-63751-1

- Jassem, Wiktor (2003), "Polish", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33 (1): 103–107, doi:10.1017/S0025100303001191

- Ladefoged, Peter (1999), "American English", Handbook of the International Phonetic Association (Cambridge Univ. Press): 41–44

- Merrill, Elizabeth (2008), "Tilquiapan Zapotec" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 38 (1): 107–114, doi:10.1017/S0025100308003344

- Pavlík, Radoslav (2004), "Slovenské hlásky a medzinárodná fonetická abeceda" (PDF), Jazykovedný časopis, 55: 87–109

- Peters, Jörg (2006), "The dialect of Hasselt", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 36 (1): 117–124, doi:10.1017/S0025100306002428

- Pop, Sever (1938), Micul Atlas Linguistic Român, Muzeul Limbii Române Cluj

- Ternes, Elmer; Vladimirova-Buhtz, Tatjana (1999), "Bulgarian", Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, Cambridge University Press, pp. 55–57, ISBN 0-521-63751-1

- Thelwall, Robin; Sa'Adeddin, M. Akram (1990), "Arabic", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 20 (2): 37–41, doi:10.1017/S0025100300004266

- Thomas, Erik R. (2004), "Rural Southern white accents", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 300–324, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Thorén, Bosse; Petterson, Nils-Owe (1992), Svenska Utifrån Uttalsanvisningar, ISBN 91-520-0284-5

- Trouvain, Jürgen; Gilles, Peter (2009), PhonLaf - Phonetic Online Material for Luxembourgish as a Foreign Language 1 (PDF), pp. 74–77

- Vanvik, Arne (1979), Norsk fonetik, Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo, ISBN 82-990584-0-6

- Verhoeven, Jo (2007), "The Belgian Limburg dialect of Hamont", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 37 (2): 219–225, doi:10.1017/S0025100307002940

- Wells, J.C. (1982), Accents of English, 2: The British Isles, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Zamora Vicente, Alonso (1967), Dialectología española (2nd ed.), Biblioteca Romanica Hispanica, Editorial Gredos

External links

- The cardinal vowels with Daniel Jones (sound recordings with an animated vowel chart in YouTube).