Golden Horde

| Golden Horde Ulus of Jochi | |||||

| Зүчийн улс | |||||

| Nomadic empire Division of the Mongol Empire | |||||

| |||||

|

| |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Sarai Batu | ||||

| Languages |

| ||||

| Religion | Tengrism Shamanism Christianity Tibetan Buddhism (1240s–1313) Islam (1313–1502) | ||||

| Government | Semi-elective monarchy, later hereditary monarchy | ||||

| Khan | |||||

| • | 1226–1280 | Orda Khan (White Horde) | |||

| • | 1242–1255 | Batu Khan (Blue Horde) | |||

| • | 1379–1395 | Tokhtamysh | |||

| • | 1435–1459 | Küchük Muhammad (Great Horde) | |||

| • | 1481–1498, 1499–1502 | Shaykh Ahmad | |||

| Legislature | Kurultai | ||||

| Historical era | Late Middle Ages | ||||

| • | Established after the Mongol invasion of Rus' | 1240s | |||

| • | Blue Horde and White Horde united | 1379 | |||

| • | Disintegrated into Great Horde | 1466 | |||

| • | Last remnant subjugated by the Crimean Khanate | 1502 | |||

| Area | |||||

| • | 1310[3][4] | 6,000,000 km² (2,316,613 sq mi) | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

| a Their state came to be known in historiography as the Golden Horde or the ulus ("people" or "patrimony") of Djochi, while the contemporaries simply referred to it as the Great Horde (ulu orda).[2] | |||||

The Golden Horde (Mongolian: Алтан Ордын улс Altan Ordīn uls; Russian: Золотая Орда, tr. Zolotaja Orda; Tatar: Алтын Урда Altın Urda) was a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire.[5] With the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire after 1259 it became a functionally separate khanate. It is also known as the Kipchak Khanate or as the Ulus of Jochi.[6]

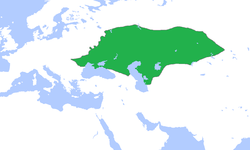

After the death of Batu Khan (the founder of the Golden Horde) in 1255, his dynasty flourished for a full century, until 1359, though the intrigues of Nogai did instigate a partial civil war in the late 1290s. The Horde's military power peaked during the reign of Uzbeg (1312–1341), who adopted Islam. The territory of the Golden Horde at its peak included most of Eastern Europe from the Urals to the Danube River, and extended east deep into Siberia. In the south, the Golden Horde's lands bordered on the Black Sea, the Caucasus Mountains, and the territories of the Mongol dynasty known as the Ilkhanate.[6]

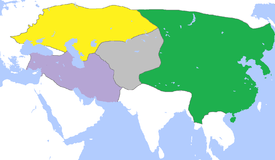

The khanate experienced violent internal political disorder beginning in 1359, before it briefly reunited (1381-1395) under Tokhtamysh. However, soon after the 1396 invasion of Timur, the founder of the Timurid Empire, the Golden Horde broke into smaller Tatar khanates which declined steadily in power. At the start of the 15th century the Horde began to fall apart. By 1466 it was being referred to simply as the "Great Horde". Within its territories there emerged numerous predominantly Turkic-speaking khanates. These internal struggles allowed the northern vassal state of Muscovy to rid itself of the "Tatar Yoke" at the Great stand on the Ugra river in 1480. The Crimean Khanate and the Kazakh Khanate, the last remnants of the Golden Horde, survived until 1783 and 1847 respectively.

Name

The name Golden Horde is said to have been inspired by the golden color of the tents the Mongols lived in during wartime, or an actual golden tent used by Batu Khan or by Uzbek Khan,[7] or to have been bestowed by the Slavic tributaries to describe the great wealth of the khan. But the Mongolic word for the color yellow (Sarı/Saru) also meant "center" or "central" in Old Turkic and Mongolic languages, and "horde" probably comes from the Mongolic word ordu, meaning palace, camp or headquarters, so "Golden Horde" may simply have come from a Mongolic term for "central camp."[8] In any event, it was not until the 16th century that Russian chroniclers begin explicitly using the term "Golden Horde" (Russian: Золотая Орда) to refer to this particular successor khanate of the Mongol Empire. The first known use of the term, in 1565, in the Russian chronicle History of Kazan, applied it to the Ulus of Batu (Russian: Улуса Батыя), centered on Sarai.[9][10] In contemporary Persian, Armenian and Muslim writings, and in the records of the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries such as the Yuanshi and the Jami' al-tawarikh, the khanate was called the "Ulus of Jochi" ("realm of Jochi" in Mongolian), "Dasht-i-Qifchaq" (Qipchaq Steppe) or "Khanate of the Qipchaq" and "Comania" (Cumania).[11][12]

Its left wing (or "left hand" in official Mongolian-sponsored Persian sources) was referred to as the Blue Horde in Russian chronicles and as the White Horde in Timurid sources (e.g. Zafar-Nameh). Western scholars have tended to follow the Timurid sources' nomenclature and call the left wing the White Horde. But Ötemish Hajji (fl.1550), a historian of Khwarezm, called the left wing the Blue Horde, and since he was familiar with the oral traditions of the khanate empire, it seems likely that the Russian chroniclers were correct, and that the khanate itself called its left wing the Blue Horde.[13] The khanate apparently used the term White Horde to refer to its right wing, which was situated in Batu's home base in Sarai and controlled the ulus. However, the designations Golden Horde, Blue Horde, and White Horde have not been encountered in the sources of the Mongol period.[14]

Mongol origins (1225–1241)

At his death in 1227, Genghis Khan divided the Mongol Empire amongst his four sons as appanages, but the Empire remained united under the supreme khan. Jochi was the eldest, but he died six months before Genghis. The westernmost lands occupied by the Mongols, which included what is today southern Russia and Kazakhstan, were given to Jochi's eldest sons, Batu, who eventually became the ruler of the Blue Horde, and Orda, who became the leader of the White Horde.[15][16] In 1235, Batu with the great general Subedei began an invasion westwards, first conquering the Bashkirs and then moving on to Volga Bulgaria in 1236. From there he conquered some of the southern steppes of present-day Ukraine in 1237, forcing many of the local Cumans to retreat westward. The military campaign against the Kypchaks and Cumans had started under Jochi and Subedei in 1216–18 when the Merkits took shelter among them. By 1239 a large portion of Cumans were driven out of the Crimea peninsula, and it became one of the appanages of the Mongol Empire.[17] The remnants of the Crimean Cumans survived in the Crimean mountains, and they would, in time, mix with other groups in the Crimea (including Greeks, Goths, and Mongols) to form the Crimean Tatar population. Moving north, Batu began the Mongol invasion of Rus' and for three years subjugated the principalities of former Kievan Rus', whilst his cousins Möngke, Kadan, and Güyük moved southwards into Alania.

Using the migration of the Cumans as their casus belli, the Mongols continued west, raiding Poland and Hungary and culminating in the battles of Legnica and Mohi. In 1241, however, Ögedei Khan died in the Mongolia homeland. Batu turned back from his siege of Vienna to take part in disputing the succession. The Mongol armies would never again travel so far west. In 1242, after retreating through Hungary, destroying Pest in the process, and subjugating Bulgaria,[18] Batu established his capital at Sarai, commanding the lower stretch of the Volga River, on the site of the Khazar capital of Atil. Shortly before that, the younger brother of Batu and Orda, Shiban, was given his own enormous ulus east of the Ural Mountains along the Ob and Irtysh Rivers.

While the Mongolian language was undoubtedly in general use at the court of Batu, few Mongol texts written in the territory of the Golden Horde have survived, perhaps because of the prevalent general illiteracy. According to Grigor'ev, yarliq, or decrees of the Khans, were written in Mongol, then translated into the Cuman language. The existence of Arabic-Mongol and Persian-Mongol dictionaries dating from the middle of the 14th century and prepared for the use of the Mamluks in Egypt suggests that there was a practical need for such works in the chancelleries handling correspondence with the Golden Horde. It is thus reasonable to conclude that letters received by the Mamluks – if not also written by them – must have been in Mongol.[18] Indeed, the linguistic and even socio-linguistic impacts were great, as the Russians borrowed thousands of words, phrases, and other significant linguistic features from the Mongol and Turkic languages that were united under the Mongol Empire.[19]

Golden Age

Early rulers under the Great Khans (1241–1259)

When the Great Khatun Töregene invited Batu to elect the next Emperor of the Mongol Empire in 1242, he declined to attend a kurultai, thus delaying the succession for several years. Although Batu stated he was suffering from old age and illness and politely refused the invitation, it seems that he did not support the election of Güyük Khan because Güyük and Büri, grandson of Chagatai Khan, had quarreled violently with Batu at a victory banquet during the Mongol occupation of Eastern Europe. Finally, he sent his brothers to the kurultai, and the new Emperor of the Mongols was elected in 1246. All the senior Rus' princes, including Yaroslav II of Vladimir, Danylo of Halych, and Sviatoslav Vsevolodovich of Vladimir, acknowledged Batu's supremacy. However, the Mongol court exterminated some anti-Mongol princes, such as Michael of Chernigov, who had killed a Mongol envoy in 1240.

After a short time, Güyük called Batu to pay him homage several times. Batu sent Andrey and Alexander Nevsky to Karakorum in Mongolia in 1247 after their father's death. Güyük appointed Andrey Grand prince of Vladimir-Suzdal and Alexander prince of Kiev.[20] In 1248, he demanded Batu come eastward to meet him, a move that some contemporaries regarded as a pretext for Batu's arrest. In compliance with the order, Batu approached, bringing a large army. When Güyük moved westwards, Tolui's widow and a sister of Batu's stepmother Sorghaghtani warned Batu that the Jochids might be his target.

Güyük died on the way, in what is now Xinjiang, at about the age of forty-two. Although some modern historians believe that he died of natural causes because of deteriorating health,[21] he may have succumbed to the combined effects of alcoholism and gout, or he may have been poisoned. William of Rubruck and a Muslim chronicler state that Batu killed the imperial envoy, and one of his brothers murdered the Great Khan Güyük, but these claims are not completely corroborated by other major sources. Güyük's widow Oghul Qaimish took over as regent, but she would be unable to keep the succession within her branch of the family.

With the assistance of the Golden Horde, Möngke succeeded as Great Khan in 1251. Utilizing the discovery of a plot designed to remove him, Möngke as the new Great Khan began a purge of his opponents. Estimates of the deaths of aristocrats, officials, and Mongol commanders range from 77–300. Batu became the most influential person as his friendship with Möngke ensured the unity of the empire. Batu, Möngke, and other princely lines shared rule over the area from Afghanistan to Turkey.

Batu allowed Möngke's census takers to operate freely in his realm, though his prestige as kingmaker and elder Borjigin was at its height. In 1252–59, Möngke conducted a census of the Mongol Empire, including Iran, Afghanistan, Georgia, Armenia, Russia, Central Asia, and North China. While the census in China was completed in 1252, Novgorod in the far northwest was not counted until winter 1258–59. There was an uprising in Novgorod against the Mongol census, but Alexander Nevsky forced the city to submit to the census and taxation.

The Grand Prince Andrey II gave umbrage to the Mongols. Batu sent a punitive expedition under Nevruy. On their approach, Andrey fled to Pskov, and thence to Sweden. The Mongols overran Vladimir and harshly punished the principality. The Livonian Knights stopped their advance to Novgorod and Pskov. Thanks to his friendship with Sartaq, Alexander was installed as the Grand Prince of Vladimir (i.e., the supreme Russian ruler) by Batu in 1252. In 1256 Andrey traveled to Sarai to ask pardon for his former infidelity and was shown mercy.

Möngke ordered the Jochid and Chagatayid families to join Hulagu's expedition to Iran. Berke's persuasion might have forced his brother Batu to postpone Hulagu's operation, little suspecting that it would result in eliminating the Jochid predominance there for several years. During the reign of Batu or his first two successors, the Golden Horde dispatched a large Jochid delegation to participate in Hulagu's expedition in the Middle East in 1256/57.

After Batu died in 1256, his son Sartaq was appointed by Möngke. As soon as he returned from the court of the Great Khan in Mongolia, Sartaq died. After a brief reign of an infant Ulaghchi under the regency of Boragchin Khatun, Batu's younger brother Berke was enthroned as khan of the Jochids in 1257.

In 1257, Danylo repelled Mongol assaults led by the prince Kuremsa on Ponyzia and Volhynia and dispatched an expedition with the aim of taking Kiev. Despite initial successes, in 1259 a Mongol force under Boroldai entered Galicia and Volhynia and offered an ultimatum: Danylo was to destroy his fortifications or Boroldai would assault the towns. Danylo complied and pulled down the city walls. In 1259 Berke launched savage attacks on Lithuania and Poland, and demanded the submission of Béla IV, the Hungarian monarch, and the French King Louis IX in 1259 and 1260.[22] His assault on Prussia in 1259/60 inflicted heavy losses on the Teutonic Order.[23] The Lithuanians were probably tributary in the 1260s, when reports reached the Curia that they were in league with the Mongols.[24]

Civil war of the Mongols (1260–1280)

After Möngke Khan died in 1259, the Toluid Civil War broke out between Kublai Khan and Ariq Böke. While Hulagu supported Kublai, Berke threw his allegiance to Ariq Böke.[25] He also minted coins in Ariq Böke's name.[26] However, Berke remained neutral militarily, and after the defeat of Ariq Böke, freely acceded to Kublai's enthronement.[27] However, some elites of the White Horde joined Ariq Böke's resistance.

One of the Jochid princes who joined Hulagu's army was accused of witchcraft and sorcery against Hulagu. After receiving permission from Berke, Hulagu executed him. After that two more Jochid princes died suspiciously. According to some Muslim sources, Hulagu refused to share his war booty with Berke in accordance with Genghis Khan's wish. Berke was a devoted Muslim who had had a close relationship with the Abbasid Caliph Al-Musta'sim, who had been killed by Hulagu in 1258. The Jochids believed that Hulagu's state eliminated their presence in the Transcaucasus.[28] Those events increased the anger of Berke and the war between the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate soon broke out in 1262.

In 1262 a rebellion erupted in Suzdal, killing Mongol darughachis and tax-collectors. Berke planned a severe punitive expedition. But after Alexander Nevsky begged Berke not to punish the Russian people and the Vladimir-Suzdal cities agreed to pay a large indemnity, Berke relented.

The increasing tension between Berke and Hulagu was a warning to the Golden Horde contingents in Hulagu's army that they had better escape. One section reached the Kipchak Steppe, another traversed Khorasan and a third body took refuge in Mamluk ruled Syria where they were well received by Sultan Baybars (1260–77). Hulagu harshly punished the rest of the Golden Horde army in Iran. Berke sought a joint attack with Baybars and forged an alliance with the Mamluks against Hulagu. The Golden Horde dispatched Nogai to invade the Ilkhanate but Hulagu forced him back in 1262. The Ilkhanids then crossed the Terek River, capturing an empty Jochid encampment, only to be routed in a surprise attack by Nogai's forces. Many of them were drowned as the ice broke on the frozen Terek River.

.jpeg)

When the former Seljuk Sultan Kaykaus II was arrested in the Byzantine Empire, his younger brother Kayqubad II appealed to Berke. An Egyptian envoy was also detained there. With the assistance of the Kingdom of Bulgaria (Berke's vassal), Nogai invaded the Empire in 1264. He forced Michael VIII Palaiologos to release Kaykaus, pay tribute to the Horde, and marry one of his daughters, Euphrosyne Palaiologina, to Nogai. Berke gave Kaykaus Crimea as an appanage and had him marry a Mongol woman.

Ariq Böke had earlier placed Chagatai's grandson Alghu as Chagatayid Khan, ruling Central Asia. He took control of Samarkand and Bukhara. When the Muslim elites and the Jochid retainers in Bukhara declared their loyalty to Berke, Alghu smashed the Golden Horde appanages in Khorazm. Alghu insisted Hulagu attack the Golden Horde; he accused Berke of purging his family in 1252. In Bukhara, he and Hulagu slaughtered all the retainers of the Golden Horde and reduced their families into slavery, sparing only the Great Khan Kublai's men.[29] After Berke gave his allegiance to Kublai, Alghu declared war on Berke, seizing Otrar and Khorazm. While the left bank of Khorazm would eventually be retaken, Berke had lost control over Transoxiana. In 1264 Berke marched past Tiflis to fight against Hulagu's successor Abagha, but he died en route.

Batu's grandson Mengu-Timur was nominated by Kublai and succeeded his uncle Berke.[30] However, Mengu-Timur secretly supported the Ögedeid prince Kaidu against Kublai and the Ilkhanate. After the defeat of Baraq (Chagatai Khan), a peace treaty was made among Mengu-Timur, Kaidu and him in c.1267. One-third of Transoxiana was granted to Kaidu and Mengu-Timur according to this peace treaty.[31] In 1268, when a group of princes operating in Central Asia on Kublai's behalf mutinied and arrested two sons of the Qaghan (Great Khan), they sent them to Mengu-Timur. One of them, Nomoghan, favorite of Kublai, was located in the Crimea.[32] Mengu-Timur might have struggled with Hulagu's successor Abagha for a brief period of time, but the Great Khan Kublai forced them to sign a peace treaty.[33] He was allowed to take his share in Persia. Independently from the Khan, Nogai expressed his desire to ally with Baybars in 1271. Despite the fact that he was proposing a joint attack on Iran with the Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo), Mengu-Timur congratulated Abagha when Baraq was defeated by the Ilkhan in 1270.[34]

In 1267, Mengu-Timur issued a diploma – jarliq – to exempt Rus' clergy from any taxation and gave to the Genoese and Venice exclusive rights to hold Caffa and Azov. Some of Mengu-Timur's relatives converted to Christianity at the same time and settled among the Rus' people. Even though Nogai invaded the Orthodox Christian Byzantine Empire in 1271, the Khan sent his envoys to maintain friendly relationship with Michael VIII Palaiologos. He ordered the Grand prince of Rus to allow German merchants free travel through his lands. This gramota says:

Mengu-Timur's word to Prince Yaroslav: give the German merchants way into your lands. From Prince Yaroslav to the people of Riga, to the great and the young, and to all: your way is clear through my lands; and who comes to fight, with them I do as I know; but for the merchant the way is clear.[35]

This decree also allowed Novgorod's merchants travel throughout the Suzdal lands without restraint.[36] Mengu Timur honored his vow: when the Danes and the Livonian Knights attacked the north-western lands of the Rus in 1269, the Khan's great basqaq (darughachi), Amraghan, and many Mongols assisted the Russian army assembled by the Grand duke Yaroslav. The Germans and the Danes were so cowed that they sent gifts to the Mongols and abandoned the region of Narva.[37] The Mongol Khan's authority extended to all Russian principalities, and in 1274–75 the census took place in all Rus' cities, including Smolensk and Vitebsk.[38]

Dual khanship (1281–1299)

Mengu-Timur was succeeded in 1281 by his brother Töde Möngke, who was a Muslim. He made peace with Kublai, returned his sons to him, and acknowledged his supremacy.[39][40] Nogai and Köchü, Khan of the White Horde and son of Orda Khan, also made peace with the Yuan dynasty and the Ilkhanate. According to Mamluk historians, Töde Möngke sent the Mamluks a letter proposing to fight against their common enemy, the unbelieving Ilkhanate. This indicates that he might have had an interest in Azerbaijan and Georgia, which were both ruled by the Ilkhans.

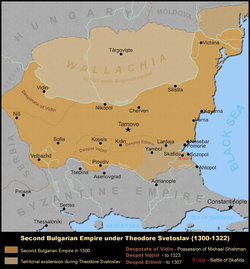

In the 1270s Nogai savagely raided Bulgaria[41] and Lithuania.[42] He blockaded Michael Asen II inside Drăstăr in 1279, executed the rebel emperor Ivailo in 1280, and forced George Terter I to seek refuge in the Byzantine Empire in 1292. In 1284 Saqchi came under the Mongol rule during the major invasion of Bulgaria, and coins were struck in the Khan's name.[43] Smilec became emperor of Bulgaria according to the wishes of Nogai Khan, who helped his allies the Byzantines. Accordingly, the reign of Smilec has been considered the height of Mongol over-lordship in Bulgaria. When he was expelled by a local boyar c.1295, the Mongols launched another invasion of Bulgaria to protect their protege. Nogai compelled Stefan Uroš II Milutin of Serbia to accept the Mongol supremacy and received his son, Stefan Dečanski, as hostage in 1287. Under his rule, the Vlachs, Slavs, Alans, and Turco-Mongols lived in modern-day Moldavia. After their failed but devastating invasion of Hungary in 1285, Nogai, Talabuga, and other noyans overthrew Töde Möngke because he was not an active Khan surrounded by clerics and sheikhs. Talabuga was elected as Khan, and Töde Möngke was left to live in peace. In addition to his attack on Poland in 1287, Talabuga's army made unsuccessful attempts to invade the Ilkhanate in 1288 and 1290.

At the same time, the influence of Nogai greatly increased in the Golden Horde. Backed by him, some Rus' princes, such as Dmitry of Pereslavl, refused to come to the court of the Khan in Sarai, while Dmitry's brother Andrey of Gorodets sought assistance from Töde Möngke. Nogai vowed to support Dmitry in his struggle for the grand ducal throne. On hearing about this, Andrey renounced his claims to Vladimir and Novgorod and returned to Gorodets. In 1285 Andrey again led a Mongol army under the Borjigin prince to Russia, but Dmitry expelled them. Under Nogai, the western part of the Horde and its vassals became de facto independent. During the punitive expedition against the Circassians, the Khan's suspicion of Nogai increased. Talabuga challenged Nogai, who organized a coup and replaced him with Toqta in 1291. Mikhail Yaroslavich was summoned to appear before Nogai in Sarai, and Daniel of Moscow declined to come. In 1293 Toqta sent a punitive expedition led by his brother, Tudaun (Dyeden in Russian chronicles), to Russia and Belarus to punish those stubborn subjects. The latter sacked fourteen major cities, finally forcing Dmitry to abdicate.

Nogai's daughter married a son of Kublai's niece, Kelmish, who was wife of a Qongirat general of the Golden Horde. Nogai was angry with Kelmish's family because her Buddhist son despised his Muslim daughter. For this reason, he demanded Toqta send Kelmish's husband to him. Nogai's independent actions related to Rus' princes and foreign merchants had already annoyed the Khan. The Khan thus refused and declared war on Nogai. Toqta was defeated in their first battle. When the legitimate Khan Toqta tried a second time, Nogai was killed in battle in 1299 at the Kagamlik, near the Dnieper. Toqta had his son stationed in Saqchi and along the Danube as far as the Iron Gate.[44] Nogai's son Chaka, who had briefly made himself Emperor of Bulgaria, was murdered by Theodore Svetoslav on the orders of Toqta.[45]

After Mengu-Timur died, rulers of the Golden Horde withdrew their support from Kaidu, the head of the House of Ögedei. Kaidu tried to restore his influence in the Golden Horde by sponsoring his own candidate Kobeleg against Bayan (r. 1299–1304), Khan of the White Horde.[46] After taking military support from Toqta, Bayan asked help from the Yuan dynasty and the Ilkhanate to organize a unified attack on the Chagatai Khanate under the leadership of Kaidu and his number two Duwa. However, the Yuan court was unable to send quick military support.[47]

General peace (1299–1312)

From 1300 to 1303 a severe drought occurred in the areas surrounding the Black Sea. Toqta allowed the remnants of Nogai's followers to live in his lands. He demanded that the Ilkhan Ghazan and his successor Oljeitu give Azerbaijan back but was refused. Then he sought assistance from Egypt against the Ilkhanate. Toqta made his man ruler in Ghazna, but he was expelled by its people. Toqta dispatched a peace mission to the Ilkhan Gaykhatu in 1294, and peace was maintained mostly uninterrupted until 1318.[48]

In 1304 ambassadors from the Mongol rulers of Central Asia and the Yuan announced to Toqta their general peace proposal. Toqta immediately accepted the supremacy of Yuan emperor Temür Öljeytü, and all yams (postal relays) and commercial networks across the Mongol khanates reopened. Toqta introduced the general peace among the Mongol khanates to Rus' princes at the assembly in Pereyaslavl.[49] The Yuan influence seemed to have increased in the Golden Horde as some of Toqta's coins carried 'Phags-pa script in addition to Mongolian script and Persian characters.[50]

The Khan arrested the Italian residents of Sarai and besieged Caffa in 1307. The cause was apparently Toqta's displeasure at the Genoese slave trade of his subjects, who were mostly sold as soldiers to Egypt.[52] The Genoese resisted for a year, but in 1308 they set fire to their city and abandoned it. Relations between the Italians and the Golden Horde remained tense until Toqta's death.

The Khan was married to Mary, illegitimate daughter of the Byzantine Emperor, securing the Byzantine-Mongol alliance after the defeat of Nogai.[53] A report reached Western Europe that Toqta was highly favourable to the Christians.[54] According to Muslim observers, however, Toqta remained an idol-worshiper (Buddhism and Tengerism) and showed favour to religious men of all faiths, though he preferred Muslims.[55]

During the late reign of Toqta, tensions between princes of Tver and Moscow became violent. Toqta might have considered eliminating the special status of the Grand principality of Vladimir, placing all the Rus' princes on the same level. Toqta decided to personally visit northern Russia, but he died while crossing the Volga in 1313.[56]

Political evolution (1312–1359)

After Uzbeg (Öz-Beg) assumed the throne in 1313, he adopted Islam as the state religion. He proscribed Buddhism and Shamanism among the Mongols in Russia, thus reversing the spread of the Yuan culture. By 1315, Uzbeg had successfully Islamicized the Horde, killing Jochid princes and Buddhist lamas who opposed his religious policy and succession of the throne. Uzbeg Khan continued the alliance with the Mamluks begun by Berke and his predecessors. He kept a friendly relationship with the Mamluk Sultan and his shadow Caliph in Cairo. After a long delay and much discussion, he married a princess of the blood to Al-Nasir Muhammad, Sultan of Egypt.

The policy of Mongol rulers regarding the Rus' was to constantly switch alliances in an attempt to keep Russia and Eastern Europe weak and divided. With the assistance of Sarai, the Grand duke Mikhail Yaroslavich won the battle against the party in Novgorod in 1316. While Michael was asserting his authority, his rival Yury of Moscow ingratiated himself into the favor of Uzbeg so that he appointed him chief of the Rus' princes and gave him his sister, Konchak, in marriage. After spending three years at Uzbeg's court, Yury returned with an army of Mongols and Mordvins. After he ravaged the villages of Tver, Yury was defeated by Mikhail in December 1318, and his new wife and the Mongol general, Kawgady, were captured. While she stayed in Tver, Konchak, who converted to Christianity and adopted the name Agatha, died. Mikhail's rivals suggested to Uzbeg Khan that he had poisoned the Khan's sister and revolted against his rule. Mikhail was summoned to Sarai and executed on November 22, 1318.[57][58] In 1322, Mikhail's son, Dmitry, seeking revenge for his father's murder, went to Sarai and persuaded the Khan that Yury had appropriated a large portion of the tribute due to the Horde. Yury was summoned to the Horde for a trial, but he was killed by Dmitry before any formal investigation. Eight months later, Dmitry was also executed by the Horde for his crime.

At first Uzbeg did not want to empower Moscow. In 1327, the Baskaki Shevkal, cousin of Uzbeg, arrived in Tver from the Horde, with a large retinue. They took up residence at Aleksander's palace. Rumors spread that Shevkal wanted to occupy the throne for himself and introduce Islam to the city. When, on 15 August 1327, the Mongols tried to take a horse from a deacon named Dyudko, he cried for help and a mob of furious people fell on the Tatars and killed them all. Shevkal and his remaining guards were burnt alive. Thus Uzbeg Khan began backing Moscow as the leading Russian state. Ivan I Kalita was granted the title of grand prince and given the right to collect taxes from other Russian potentates. The Khan also sent Ivan at the head of an army of 50,000 soldiers to punish Tver. Aleksander was shown mercy in 1335, however, when Moscow requested that he and his son Feoder be quartered in Sarai by orders of the Khan on October 29, 1339.

Uzbeg, whose total army exceeded 300,000, repeatedly raided Thrace, partly in service of Bulgaria's war against Byzantium and Serbia beginning in 1319. The Byzantine Empire under Andronikos II Palaiologos and Andronikos III Palaiologos was raided by the Golden Horde between 1320 and 1341, until the Byzantine port of Vicina Macaria was occupied. Some sources report that Uzbeg also married Andronikos III's illegitimate daughter, who had taken the name Bayalun, and who later, after relations between the Horde and the Byzantines deteriorated, fled back to the Byzantine Empire, apparently fearing her forced conversion to Islam.[59][60] His armies pillaged Thrace for forty days in 1324 and for fifteen days in 1337, taking 300,000 captives. However, his attempt to reassert Mongol control over Serbia in 1330 was unsuccessful.[61] Backed by Uzbeg, Basarab I of Wallachia declared an independent state from the Hungarian crown in 1330.[51]

Uzbeg allowed the Genoese to settle in Crimea after his accession, but the Mongols sacked their outpost Sudak in 1322 when the Christians defied the Muslims in the city.[62] The Genoese merchants in the other towns were not molested. Pope John XXII requested Uzbeg to restore Roman Catholic churches destroyed in the region. Thus, the Khan signed a new trade treaty with the Genoese in 1339 and allowed them to rebuild the walls of Kaffa. In 1332 he had allowed the Venetians to establish a colony at Tanais on the Don. A decree, issued probably by Mengu-Timur, allowing the Franciscans to proselytize, was renewed by Uzbeg in 1314.

The Golden Horde invaded the Ilkhanate under Abu Sa'id in 1318, 1324, and 1335. Uzbeg's ally Al-Nasir refused to attack Abu Sa'id because the Ilkhan and the Mamluk Sultan signed a peace treaty in 1323. In 1326 Uzbeg reopened friendly relations with the Empire of the Great Khan and began to send tributes thereafter.[63] From 1339 he received annually 24,000 ding in Yuan paper currency from the Jochid appanages in China.[64] When the Ilkhanate collapsed after Abu Sa'id's death, its senior-beys approached Uzbeg in their desperation to find a leader, but the latter declined after consulting with his senior emir, Qutluq Timür.

In 1323 Grand Duke Gediminas of Lithuania gained control of Kiev and installed his brother Fedor as prince, but the principality's tribute to the Khan continued. On a campaign a few years later, the Lithuanians under Fedor included the Khan's basqaq in their entourage.[65]

Under Uzbeg and his successor Janibeg (1342–1357), Islam, which among some of the Turks in Eurasia had deep roots going back into pre-Mongol times, gained general acceptance, though its adherents remained tolerant of other beliefs. In order to successfully expand Islam, the Mongols built a mosque and other "elaborate places" requiring baths — an important element of Muslim culture. Sarai attracted merchants from other countries. The slave trade flourished due to strengthening ties with the Mamluk Sultanate. Growth of wealth and increasing demand for products typically produce population growth, and so it was with Sarai. Housing in the region increased, which transformed the capital into the center of a large Muslim Sultanate.

Janibeg sponsored joint Mongol-Rus' military expeditions against Lithuania and Poland. In 1344 his army marched against Poland with auxiliaries from Galicia–Volhynia, as Volhynia was part of Lithuania. In 1349, however, Galicia–Volhynia was occupied by a Polish-Hungarian force, and the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia was finally conquered and incorporated into Poland. This act put an end to the relationship of vassalage between the Galicia–Volhynia Rus' and the Golden Horde.[66]

The Black Death of the 1340s was a major factor contributing to the economic downfall of the Golden Horde. Janibeg abandoned his father's Balkan ambitions and backed Moscow against Lithuania and Poland. He also asserted Jochid dominance over the Chagatai Khanate and conquered Tabriz, ending Chobanid rule there in 1356. After accepting the surrender of the Jalayirids, Janibeg boasted that three uluses of the Mongol Empire were under his control. The Polish King, Casimir III the Great, submitted to the Horde and undertook to pay tribute in order to avoid more conflicts.[67] The seven Mongol princes were sent by Janibeg to assist Poland.[68] Following the subsequent assassination of Janibeg, the Golden Horde quickly lost Azerbaijan to the Jalayir king Shaikh Uvais in 1357.

Decline

Great troubles (1359–1381)

Following the assassination of Berdibek by his brother in 1359, the Khanate sank into prolonged internecine war, in which sometimes as many as four Khans vied for recognition by the emirs and for possession of major cities like Sarai, Qirim, and Azaq. After the overthrow of their nominal suzerain, Yuan Emperor Toghan Temür,[69] the Golden Horde lost touch with Mongolia and China.[70] White Horde descendants of Orda and Tuqa-Timur carried on generally free from trouble until the late 1370s. Urus Khan of the White Horde took Sarai and reunited most of the Horde from Khorazm to Desht-i-Kipchak in 1375.

By the 1380s, Shaybanids, Muscovites, and Qashan attempted to break free of the Khan's power. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania profited from this situation and pushed deeper into Golden Horde territory than in any previous expedition, and the Grand Duke Algirdas defeated forces of Murad Khan at the battle of Blue Waters c.1362.

In western Pontic steppe, Mamai, a Tatar general who was a king-maker, attempted to reassert Tatar authority over Russia. His army was defeated by the Grand prince Dmitri Donskoy at the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380, Donskoy's second consecutive victory over the Tatars. While preparing another invasion of Moscow, Mamai faced a greater challenge from the east. In 1379, Tokhtamysh, a kinsman of Urus Khan, won leadership of the White Horde with the assistance of Tamerlane. He then defeated Mamai and annexed the territory of the Blue Horde, briefly reestablishing the Golden Horde as a dominant regional power in 1381.

A brief reunion (1381–1419)

After Mamai's defeat, Tokhtamysh restored the dominance of the Golden Horde over Russia by attacking Russian lands in 1382. He besieged Moscow on August 23, but Muscovites beat off his attack, using firearms for the first time in Russian history.[71] On August 26, two sons of Tokhtamysh's supporter Dmitry of Suzdal, Dukes Vasily of Suzdal and Semyon of Nizhny Novgorod, who were present in Tokhtamysh's forces, persuaded the Muscovites to open the city gates, promising that their forces would not harm the city.[72] This allowed Tokhtamysh's troops to burst in and destroy Moscow, killing 24,000 people.[73] Tokhtamysh also crushed the Lithuanian army at Poltava in the next year.[74] Władysław II Jagiełło, Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland, accepted his supremacy and agreed to pay tribute in turn for a grant of Rus' territory.[75] For another century, Russia was forced back under the Tatar yoke.

Elated by his success, Tokhtamysh invaded Azerbaijan, Khwarezm, and Transoxiana, parts of Timur's empire, and Timur declared war against him. In 1395-1396, Timur annihilated Tokhtamysh's army, destroyed his capital, looted the Crimean trade centers, and deported the most skillful craftsmen to his own capital in Samarkand.

When Tokhtamysh fled, Urus Khan's grandson, Temür Qutlugh, was chosen Khan in Sarai, and Koirijak was appointed sovereign of the White Horde by Timur.[76] Temür Qutlugh's chief emir Edigu was the real rulers of the Golden Horde.

Tokhtamysh escaped to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and asked Vytautas for assistance in regaining his power over the Horde. In exchange for such assistance, he offered his suzerainty over the Rus' lands. Edigu defeated Tokhtamysh and Vytautas at the Battle of the Vorskla River in 1399. The trade routes never recovered from Timur's destruction, and Tokhtamysh died in obscurity in 1405. His son Jalal al-Din fled to Lithuania. While in Lithuania, he fought in the Battle of Grunwald against the Teutonic Order.

Edigu forced the Grand Prince of Moscow to accept the Khan's supremacy in 1408. Seeing Tatar commoners selling their children into slavery as damaging to both the manpower and the prestige of the Golden Horde's army, Edigu and his puppet Khan prohibited the slave trade at a kurultai. Despite some rebellions of Genghisid princes, he kept the Horde united until 1410 when he was expelled to Central Asia.

While he was absent, Jalal al-Din returned from Lithuania and briefly took the throne. Edigu returned to the Horde and set up his ordo in Crimea, challenging the sons of Tokhtamysh before his murder in 1419.

Disintegration (1420–1480)

After 1419, Olug Moxammat became Khan of the Golden Horde. However, his authority was limited to the lower banks of the Volga where Tokhtamysh's other son Kepek reigned. Together with the Khan claimant Dawlat Berdi, they were beaten by Baraq of the Uzbeks in 1421. The latter was assassinated in 1427 and Olug Moxammat reenthroned. The Lithuanian monarch Svitrigaila supported Olugh Moxammat's rival Sayid Ahmad I, who in 1433 gained the Golden Horde throne. Vasili II of Russia also supported Sayid Ahmad in order to weaken Olugh Moxammat who established the Khanate of Kazan and made Moscow a tributary. Sayid supported Švitrigaila during the Lithuanian Civil War (1431–1435).[77]

The Horde (Great Horde) broke up into separate Khanates:

- Tyumen Khanate (1468, later Khanate of Sibir)

- Khanate of Kazan (1438) – Qasim Khanate (1452)

- Khanate of Crimea (1441)

- Nogai Horde (1440s)

- Kazakh Khanate (1456)

- Khanate of Astrakhan (1466)

In the summer of 1470 (other sources give 1469), the last prominent Khan, Ahmed, organized an attack against Moldavia, the Kingdom of Poland, and Lithuania. By August 20, the Moldavian forces under Stephen the Great defeated the Tatars at the battle of Lipnic.

In 1474 and 1476, Ahmed insisted that Ivan III should recognize Russia's vassal dependence on the Horde. However, the correlation of forces was not in the Horde's favor. In 1480, Ahmed organized another military campaign against Moscow, which would result in the Horde's failure. Russia finally freed itself from the Horde, thus ending over 250 years of Tatar-Mongol control. On 6 January 1481, the Khan was killed by Ibak Khan, the prince of Tyumen, and Nogays at the mouth of the Donets River.

Fall (1480–1502)

The Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (which possessed much of the Ukraine at the time) were attacked in 1487–1491 by the remnant of the Golden Horde. They reached as far as Lublin in eastern Poland before being decisively beaten at Zaslavl.[78]

The Crimean Khanate became a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire in 1475 and subjugated what remained of the Great Horde, sacking Sarai in 1502. After seeking refuge in Lithuania, Sheikh Ahmed, last Khan of the Horde, died in prison in Kaunas some time after 1504. According to other sources, he was released from the Lithuanian prison in 1527.[79]

The Crimean Tatars wreaked havoc in southern Russia, Ukraine and even Poland in the course of the 16th and early 17th centuries, but they were not able to defeat Russia or take Moscow. Under Ottoman protection, the Khanate of Crimea continued its precarious existence until Catherine the Great annexed it on April 8, 1783. It was by far the longest-lived of the successor states to the Golden Horde.

Geography and society

Genghis Khan assigned four Mongol mingghans: the Sanchi'ud (or Salji'ud), Keniges, Uushin, and Je'ured clans to Jochi.[80] By the beginning of the 14th century, noyans from the Sanchi'ud, Hongirat, Ongud (Arghun), Keniges, Jajirad, Besud, Oirat, and Je'ured clans held importants positions at the court or elsewehere. There existed four mingghans (4,000) of the Jalayir in the left wing of the Ulus of Jochi (Golden Horde).

The population of the Golden Horde were largely a mixture of Turks and Mongols who adopted Islam later, as well as smaller amounts of Finno-Ugrians, Sarmato-Scythians, Slavs, and people from the Caucasus, among others (whether Muslim or not).[81] Most of the Horde's population was Turkic: Kipchaks, Cumans, Volga Bulgars, Khwarezmians, and others. The Horde was gradually Turkified and lost its Mongol identity, while the descendants of Batu's original Mongol warriors constituted the upper class.[82] They were commonly named the Tatars by the Russians and Europeans. Russians preserved this common name for this group down to the 20th century. Whereas most members of this group identified themselves by their ethnic or tribal names, most also considered themselves to be Muslims. Most of the population, both agricultural and nomadic, adopted the Kypchak language, which developed into the regional languages of Kypchak groups after the Horde disintegrated.

The descendants of Batu ruled the Golden Horde from Sarai Batu and later Sarai Berke, controlling an area ranging from the Volga River and the Carpathian mountains to the mouth of the Danube River. The descendants of Orda ruled the area from the Ural River to Lake Balkhash. Censuses recorded Chinese living quarters in the Tatar parts of Novgorod, Tver and Moscow.

Internal organization

The Golden Horde's elites were descended from four Mongol clans, Qiyat, Manghut, Sicivut and Qonqirat. Their supreme ruler was the Khan, chosen by the kurultai among Batu Khan's descendants. The prime minister, also ethnically Mongol, was known as "prince of princes", or beklare-bek. The ministers were called viziers. Local governors, or basqaqs, were responsible for levying taxes and dealing with popular discontent. Civil and military administration, as a rule, were not separate.

The Horde developed as a sedentary rather than nomadic culture, with Sarai evolving into a large, prosperous metropolis. In the early 14th century, the capital was moved considerably upstream to Sarai Berqe, which became one of the largest cities of the medieval world, with 600,000 inhabitants.[83]

Despite Russian efforts at proselytizing in Sarai, the Mongols clung to their traditional animist or shamanist beliefs until Uzbeg Khan (1312–41) adopted Islam as a state religion. Several rulers of Kievan Rus' – Mikhail of Chernigov and Mikhail of Tver among them – were reportedly assassinated in Sarai, but the Khans were generally tolerant and even released the Russian Orthodox Church from paying taxes.

Vassals and allies

The Horde exacted tax payments from its subject peoples – Rus' people, Armenians, Georgians, Circassians, Alans, Crimean Greeks, Crimean Goths, and others (Bulgarians, Vlachs). The territories of Christian subjects were regarded as peripheral areas of little interest as long as they continued to pay taxes. These vassal states were never fully incorporated into the Horde, and Russian rulers early obtained the privilege of collecting the Tatar tax themselves. To maintain control over Rus' and Eastern Europe, the Tatar warlords carried out regular punitive raids on their tributaries. At its height, the Golden Horde controlled the areas from Central Siberia and Khorazm to the Danube and Narva.

There is a point of view, much propagated by Lev Gumilev, that the Horde and Russian polities entered into a defensive alliance against the Teutonic knights and pagan Lithuanians. Proponents point to the fact that the Mongol court was frequented by Russian princes, notably Yaroslavl's Feodor the Black, who boasted his own ulus near Sarai, and Novgorod's Alexander Nevsky, the sworn brother (or anda) of Batu's successor Sartaq Khan. A Mongol contingent supported the Novgorodians in the Battle of the Ice and Novgorodians paid taxes to the Horde.

Sarai carried on a brisk trade with the Genoese trade emporiums on the coast of the Black Sea – Soldaia, Caffa, and Azak. Mamluk Egypt was the Khans' long-standing trade partner and ally in the Mediterranean. Berke, the Khan of Kipchak had drawn up an alliance with the Mamluk Sultan Baibars against the Ilkhanate in 1261.[84]

Provinces

The Mongols favored decimal organization, which was inherited from Genghis Khan. It is said that there were a total of ten political divisions within the Golden Horde. The Golden Horde majorly was divided into Blue Horde (Kok Horde) and White Horde (Ak Horde). Blue Horde consisted of Pontic-Caspian steppe, Khazaria, Volga Bulgaria, while White Horde encompassed the lands of the princes of the left hand: Taibugin Yurt, Ulus Shiban, Ulus Tok-timur, Ulus Ezhen Horde.

Vassal territories

- Venetian port cities in Crimea (center at Qırım). After the Mongol conquest in 1238, the port cities in Crimea paid the Jochids custom duties, and the revenues were divided among all Chingisid princes of the Mongol Empire in accordance with the appanage system.,[85]

- the banks of Azov,

- the country of Circassians,

- Walachia,

- Alania,

- Russian lands.[86]

Coin

Tulabuga's silver dirham

Tulabuga's silver dirham Obverse: "Just the Khan Tokhta" with the tamgha (imperial seal) of the House of Batu

Obverse: "Just the Khan Tokhta" with the tamgha (imperial seal) of the House of Batu Coin of Berdi Beg of the Golden Horde 762 Hijri (1359 AD).

Coin of Berdi Beg of the Golden Horde 762 Hijri (1359 AD).

Gallery

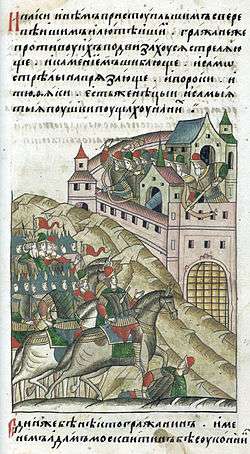

- Golden Horde raid at Rayzan

Golden Horde raid at Kyev

Golden Horde raid at Kyev Golden Horde raid at Kozelsk

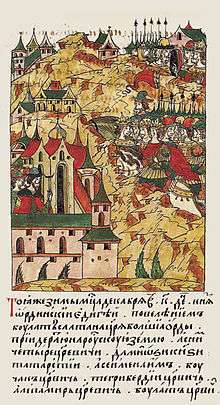

Golden Horde raid at Kozelsk Golden Horde raid Vladimir

Golden Horde raid Vladimir Golden Horde raid Suzdal

Golden Horde raid Suzdal Mongol-Tatar warriors besiege their opponents.

Mongol-Tatar warriors besiege their opponents. Mongols chase Hungarian king from Mohi, detail from Chronicon Pictum.

Mongols chase Hungarian king from Mohi, detail from Chronicon Pictum. The Mongol army captures a Rus' city

The Mongol army captures a Rus' city Mongol invasion of Hungary in 1285

Mongol invasion of Hungary in 1285 Edigu's invasion of Rus.

Edigu's invasion of Rus.

- The battle of Liegnitz, 1241. From a medieval manuscript of the Hedwig legend.

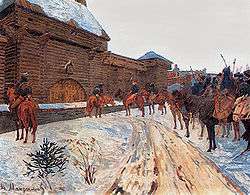

Drawing of Mongols of the Golden Horde outside Vladimir presumably demanding submission before sacking the city

Drawing of Mongols of the Golden Horde outside Vladimir presumably demanding submission before sacking the city Paiza of Abdullah Khan (r. 1361–70) with Mongolian script

Paiza of Abdullah Khan (r. 1361–70) with Mongolian script Mongol-Tatar raid

Mongol-Tatar raid A Rus' prince being punished by the Golden Horde

A Rus' prince being punished by the Golden Horde

See also

| History of the Mongols |

|---|

|

Timeline · History · Rulers · Nobility Culture · Language · Proto-Mongols |

|

|

|

- Cuman people

- Mongol invasion of Rus'

- Russo-Kazan Wars

- Tatar invasions

- Timeline of the Tataro-Mongol Yoke in Russia

- Tokhtamysh–Timur war

- Volga Bulgaria

- Division of the Mongol Empire

- Berke–Hulagu war

- List of Khans of the Golden Horde

- List of medieval Mongol tribes and clans

- List of Mongol states

- List of Turkic dynasties and countries

Reference and notes

- ↑ Zahler, Diane (2013). The Black Death (Revised Edition). Twenty-First Century Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4677-0375-8.

- 1 2 3 Kołodziejczyk (2011), p. 4.

- ↑ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of world-systems research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 498. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Perrie, Maureen, ed. (2006). The Cambridge History of Russia: Volume 1, From Early Rus' to 1689. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-521-81227-6.

- 1 2 "Golden Horde". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

Also called Kipchak Khanate Russian designation for Juchi's Ulus, the western part of the Mongol Empire, which flourished from the mid-13th century to the end of the 14th century. The people of the Golden Horde were mainly a mixture of Turkic and Uralic peoples and Sarmatians & Scythians and, to a lesser extent, Mongols, with the latter generally constituting the aristocracy. Distinguish the Kipchak Khanate from the earlier Cuman-Kipchak confederation in the same region that had previously held sway, before its conquest by the Mongols.

- ↑ Atwood (2004), p. 201.

- ↑ Gleason, Abbott (2009). A Companion to Russian History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-4443-0842-6.

- ↑ "рЕПЛХМ гНКНРЮЪ нПДЮ - НЬХАЙЮ РНКЛЮВЮ 16 ЯРНКЕРХЪ (мХК лЮЙЯХМЪ) / оПНГЮ.ПС - МЮЖХНМЮКЭМШИ ЯЕПБЕП ЯНБПЕЛЕММНИ ОПНГШ". Proza.ru. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ Ostrowski, Donald G. (Spring 2007). "Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, and: The Mongols and the West, 1221–1410, and: Daily Life in the Mongol Empire, and: The Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century (review)". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. Project MUSE. 8 (2): 431–441. doi:10.1353/kri.2007.0019.

- ↑ May, T. (2001). "Khanate of the Golden Horde (Kipchak)". North Georgia College and State University. Archived from the original on December 14, 2006.

- ↑ Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century. BRILL. p. 38. ISBN 90-04-17536-9.

- ↑ Atwood (2004), p. 41.

- ↑ Allsen (1985), pp. 5-40.

- ↑ Edward L. Keenan, Encyclopedia Americana article

- ↑ Grekov, B. D.; Yakubovski, A. Y. (1998) [1950]. The Golden Horde and its Downfall (in Russian). Moscow: Bogorodskii Pechatnik. ISBN 5-8958-9005-9.

- ↑ "History of Crimean Khanate".(English)

- 1 2 Sinor, Denis (1999). "The Mongols in the West". Journal of Asian History. Harrassowitz Verlag. 33 (1): 1–44. JSTOR 41933117.

- ↑ Dmytryshyn, 123

- ↑ Martin (2007), p. 152.

- ↑ Atwood (2004), p. 213.

- ↑ Jackson (2014), pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Annales Mellicenses. Continuatio Zwetlensis tertia, MGHS, IX, p.644

- ↑ Jackson (2014), p. 202.

- ↑ Kirakos, Istoriia p.236

- ↑ Mukhamadiev, A. G. Bulgaro-Tatarskiya monetnaia sistema, p.50

- ↑ Rashid al-Din-Jawal al Tawarikhi, (Boyle) p.256

- ↑ Jackson, Peter (1995). "The Mongols and Europe". In Abulafia, David. The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 5, C.1198-c.1300. Cambridge University Press. p. 709. ISBN 978-0-521-36289-4.

- ↑ Barthold, W. (2008) [1958]. Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion. ACLS Humanities E-Book. p. 446. ISBN 978-1-59740-450-1.

- ↑ Howorth (1880).

- ↑ Biran, Michal (2013). Qaidu and the Rise of the Independent Mongol State In Central Asia. Taylor & Francis. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-136-80044-3.

- ↑ Man, John (2012). Kublai Khan. Transworld. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-4464-8615-3.

- ↑ Saunders, J. J. (2001). The History of the Mongol Conquests. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 130–132. ISBN 0-8122-1766-7.

- ↑ Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (2005). Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260-1281. Cambridge University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-521-52290-8.

- ↑ Anton Cooper On the Edge of Empire: Novgorod's trade with the Golden Horde, p.19

- ↑ GVNP, p.13; Gramota#3

- ↑ Zenkovsky, Serge A.; Zenkovsky, Betty Jean, eds. (1986). The Nikonian Chronicle: From the year 1241 to the year 1381. Kingston Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-940670-02-0.

- ↑ Vernadsky, George; Karpovich, Michael (1943). A History of Russia: The Mongols and Russia, by George Vernadsky. Yale University Press. p. 172.

- ↑ Rashid al Din-II Successors (Boyle), p.897

- ↑ Allsen (1985), p. 21.

- ↑ Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Cambridge University Press. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0.

- ↑ Howorth (1880), p. 130.

- ↑ Byzantino Tatarica, p.209

- ↑ Baybars al Mansuri-Zubdat al-Fikra, p.355

- ↑ Spuler (1943), p. 78.

- ↑ Barthold, V.V. Four Studies on Central Asia. Translated by Minorsky, V.; Minorsky, T. Brill. p. 127.

- ↑ Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- ↑ Boyle, J. A. (1968). "Dynastic and Political History of the Il-Khans". In Boyle, J. A. The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-521-06936-6.

- ↑ G.V.Vernadsky The Mongols and Russia, p.74

- ↑ Badarch Nyamaa – The coins of Mongol empire and clan tamgna of khans (XIII–XIV) (Монеты монгольских ханов), Ch2. My collection

- 1 2 Jackson (2014), p. 204.

- ↑ Spuler (1943), p. 84.

- ↑ Vásáry, István (2005). Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-139-44408-8.

- ↑ Ptolomy of Lucca Annales, p.237

- ↑ DeWeese, Devin (2010). Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde: Baba TŸkles and Conversion to Islam in Historical and Epic Tradition. Penn State Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-271-04445-4.

- ↑ Journal of Asiatic Studies, 4th ser. xvii., 115

- ↑ Martin (2007), p. 175.

- ↑ Fennell, John (1988). "Princely Executions in the Horde 1308–1339". Forschungen zur Osteuropaischen Geschichte. 38: 9–19.

- ↑ Mihail-Dimitri Sturdza, Dictionnaire historique et Généalogique des grandes familles de Grèce, d'Albanie et de Constantinople (Great families of Greece, Albania and Constantinople: Historical and genealogical dictionary) (1983), page 373

- ↑ Saunders (2001).

- ↑ Jireuek Bulgaria, pp. 293–295

- ↑ Ibn Battuta-, 2, 414 415

- ↑ Allsen, Thomas T. (2006). The Royal Hunt in Eurasian History. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 256. ISBN 0-8122-0107-8.

- ↑ Atwood (2004), "Golden Horde".

- ↑ Rowell, S. C. (2014). Lithuania Ascending. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-107-65876-9.

- ↑ Zdan, Michael B. (June 1957). "The Dependence of Halych-Volyn' Rus' on the Golden Horde". The Slavonic and East European Review. 35 (85): 521–522. JSTOR 4204855.

- ↑ CICO-X, pp.189

- ↑ Jackson (2014), p. 211.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Mongolia and Mongol Empire

- ↑ Russia and the Golden Horde, by Charles J. Halperin, page 28

- ↑ (Russian) Dmitri Donskoi Epoch

- ↑ (Russian) History of Moscow settlements – Suchevo

- ↑ Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd edition, Entry on "Московское восстание 1382"

- ↑ René Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, p. 407

- ↑ ed. Johann Voigt, Codex diplomaticus Prussicus, 6 vols, VI, p. 47

- ↑ Howorth (1880), p. 287.

- ↑ (Lithuanian) Jonas Zinkus, et al., ed (1985–1988). "Ašmenos mūšis". Tarybų Lietuvos enciklopedija. I. Vilnius, Lithuania: Vyriausioji enciklopedijų redakcija. p. 115. LCC 86232954

- ↑ "Russian Interaction with Foreign Lands". Strangelove.net. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ Kołodziejczyk (2011), p. 66.

- ↑ Blair, Sheila; Art, Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic (1995). جامع التواريخ: Rashid Al-Din's Illustrated History of the World. Nour Foundation. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-19-727627-3.

- ↑ Halperin, Charles J. (1987). Russia and the Golden Horde: The Mongol Impact on Medieval Russian History. Indiana University Press. p. 111. ISBN 0-253-20445-3.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Mantran, Robert (Fossier, Robert, ed.) "A Turkish or Mongolian Islam" in The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 1250-1520, p. 298

- ↑ Jackson, Peter (1978). The Dissolution of the Mongol Empire. Harrassowitz. pp. 186–243.

- ↑ A. P. Grigorev and O. B. Frolova, Geographicheskoy opisaniye Zolotoy Ordi v encyclopedia al-Kashkandi-Tyurkologicheskyh sbornik, 2001, pp. 262-302

Bibliography

- Allsen, Thomas T. (1985). "The Princes of the Left Hand: An Introduction to the History of the Ulus of Ordu in the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries". Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi. V. Harrassowitz. pp. 5–40. ISBN 978-3-447-08610-3.

- Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3.

- Howorth, Sir Henry Hoyle (1880). History of the Mongols: From the 9th to the 19th Century. New York: Burt Franklin.

- Jackson, Peter (2014). The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-87898-8.

- Kołodziejczyk, Dariusz (2011). The Crimean Khanate and Poland-Lithuania: International Diplomacy on the European Periphery (15th-18th Century). A Study of Peace Treaties Followed by Annotated Documents. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 90-04-19190-9.

- Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia, 980-1584. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85916-5.

- Spuler, Bertold (1943). Die Goldene Horde, die Mongolen in Russland, 1223-1502 (in German). O. Harrassowitz.

Further reading

- Boris Grekov and Alexander Yakubovski, The Golden Horde and its Downfall

- George Vernadsky, The Mongols and Russia

- The Golden Horde, FTDNA

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Golden Horde. |

- The Golden Horde coinage

- (Russian) Golden Horde — articles at the World Archaeology