Chesapeake, Virginia

| Chesapeake, Virginia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent city | |||

| City of Chesapeake | |||

|

Great Dismal Swamp Canal | |||

| |||

| Motto: "One Increasing Purpose" | |||

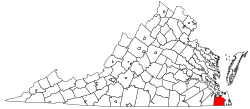

Location in the State of Virginia | |||

Chesapeake, Virginia Location in the contiguous United States | |||

| Coordinates: 36°42′51″N 76°14′18″W / 36.71417°N 76.23833°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| State |

| ||

| County | None (Independent city) | ||

| Founded | 1963 (1919 as South Norfolk, became city in 1922) | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Council-Manager | ||

| • Mayor | Alan P. Krasnoff (R) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Independent city | 910 km2 (351 sq mi) | ||

| • Land | 880 km2 (341 sq mi) | ||

| • Water | 30 km2 (10 sq mi) 2.9% | ||

| Population (2014) | |||

| • Independent city | 233,479 | ||

| • Density | 252/km2 (652/sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 1,672,319 | ||

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | ||

| ZIP codes | 23320-23328 | ||

| Area code(s) | 757 | ||

| FIPS code | 51-16000[1] | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 1496841[2] | ||

| Website | www.cityofchesapeake.net | ||

Chesapeake is an independent city located in the U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2010 census, the population was 222,209,[3] in 2013, the population was estimated to be 232,977,[4] making it the third-most populous city in Virginia.

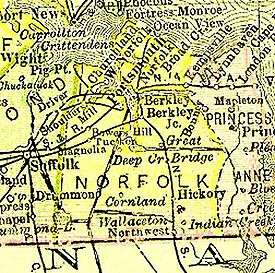

Chesapeake is included in the Virginia Beach–Norfolk–Newport News, VA–NC MSA. One of the cities in the South Hampton Roads, Chesapeake was organized in 1963 by voter referendums approving the political consolidation of the city of South Norfolk with the remnants of the former Norfolk County, which dated to 1691. (Much of the territory of the county had been annexed by other cities.) Chesapeake is the second-largest city by land area in the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Chesapeake is a diverse city in which a few urban areas are located; it also has many square miles of protected farmland, forests, and wetlands, including a substantial portion of the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. Extending from the rural border with North Carolina to the harbor area of Hampton Roads adjacent to the cities of Norfolk, Portsmouth, Suffolk, and Virginia Beach, Chesapeake is located on the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway. It has miles of waterfront industrial, commercial and residential property.

In 2011, Chesapeake was named the 21st best city in America by Bloomberg Businessweek.[5]

History

In 1963, the new independent city of Chesapeake was created when the former independent city of South Norfolk consolidated with Norfolk County. The consolidation was approved and the new name selected by the voters of each community by referendum, and authorized by the Virginia General Assembly.

Formed in 1691 in the Virginia Colony, Norfolk County had originally included essentially all the area which became the towns and later cities of Norfolk, Portsmouth, and South Norfolk. Its area was reduced after 1871 as these cities added territory through annexations. Becoming an independent city was a method for the former county to stabilize borders with neighbors, as cities could not annex territory from each other.

The relatively small city of South Norfolk had become an incorporated town within Norfolk County in 1919, and became an independent city in 1922. Its residents wanted to make a change to put their jurisdiction on a more equal footing in other aspects with the much larger cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth. In addition, by the late 1950s, although immune from annexation by the bigger cities, South Norfolk was close to losing all the county land adjoining it to the city of Norfolk in another annexation suit.

The consolidation that resulted in the city of Chesapeake was part of a wave of changes in the structure of local government in southeastern Virginia which took place between 1952 and 1975.

The Chesapeake region was among the first areas settled in the state's colonial era, when settlement started from the coast. Along Chesapeake's segment of the Intracoastal Waterway, where the Great Bridge locks marks the transition between the Southern Branch Elizabeth River and the Chesapeake and Albemarle Canal, lies the site of the Battle of Great Bridge. Fought on December 9, 1775, in the early days of the American Revolutionary War, the battle resulted in the removal of Lord Dunmore and all vestiges of English Government from the Colony and Dominion of Virginia.

Until the late 1980s and early 1990s, much of Chesapeake was either suburban or rural, serving as a bedroom community of the adjacent cities of Norfolk and Virginia Beach with residents commuting to these locations. Beginning in the late 1980s and accelerating in the 1990s, however, Chesapeake saw significant growth, attracting numerous and significant industries and businesses of its own. This explosive growth quickly led to strains on the municipal infrastructure, ranging from intrusion of saltwater into the city's water supply to congested roads and schools.

Chesapeake made national headlines in 2003 when, under a court-ordered change of venue, the community hosted the first trial of alleged Beltway sniper Lee Boyd Malvo for shootings in 2002. A jury convicted him of murder but spared him a potential death sentence; it chose a sentence of "life in prison without parole" for the young man, who was 17 years old at the time of the crime spree. A jury in neighboring Virginia Beach convicted his older partner John Allen Muhammad and sentenced him to death for another of the attacks.

See article Beltway sniper attacks

Geography

Chesapeake is located at 36°46′2″N 76°17′14″W / 36.76722°N 76.28722°W (36.767398, -76.287405).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 351 square miles (910 km2), of which 341 square miles (880 km2) is land and 10 square miles (26 km2) (2.9%) is water.[6]

The northeastern part of the Great Dismal Swamp is located in Chesapeake.

Diverse environment

Chesapeake is one of the larger cities in Virginia and the nation in terms of land area. This poses challenges to city leaders in supporting infrastructure to serve this area. In addition, the city has many historically and geographically distinct communities. City leaders are faced with conflicts between development of residential, commercial and industrial areas and preservation of virgin forest and wetlands. Within the city limits in the southwestern section is a large portion of the Great Dismal Swamp.

Adjacent counties and cities

- Portsmouth, Virginia (north)

- Norfolk, Virginia (north)

- Virginia Beach, Virginia (east)

- Currituck County, North Carolina (south)

- Camden County, North Carolina (south)

- Suffolk, Virginia (west)

Communities

Chesapeake is formally divided politically into six boroughs: South Norfolk, Pleasant Grove (not to be confused with Pleasant Grove unincorporated community in Pittsylvania County, Virginia), Butts Road, Deep Creek, Washington (not to be confused with the town of Washington in Rappahannock County, Virginia) and Western Branch.[7]

Of the current boroughs, one, South Norfolk, was formerly a separate incorporated town and independent city for much of the 20th century. Within the other boroughs, a number of communities also developed. Some of these include:

- Benefit (Pleasant Grove Borough)

- Bower's Hill (notable as a major highway junction)

- Buell

- Camelot (Western Branch Borough)

- Crestwood (Washington Borough)

- Deep Creek (Deep Creek Borough)

- Eva Gardens (Crestwood community, Washington Borough)

- Fentress (Butts Road Borough)

- Gertie

- Gilmerton

- Grassfield (Deep Creek Borough)

- Great Bridge

- Greenbrier (Washington Borough)

- Hickory (Pleasant Grove Borough)

- Hodges Ferry

- Indian River (Washington Borough)

- Mount Pleasant (Pleasant Grove Borough)

- Northwest

- Oak Grove

- Oaklette

- Portlock

- South Norfolk (South Norfolk Borough)

- Wallaceton

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Chesapeake has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[8]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1960 | 73,647 | — | |

| 1970 | 89,580 | 21.6% | |

| 1980 | 114,486 | 27.8% | |

| 1990 | 151,976 | 32.7% | |

| 2000 | 199,184 | 31.1% | |

| 2010 | 222,209 | 11.6% | |

| Est. 2015 | 235,429 | [9] | 5.9% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] 1790-1960[11] 1900-1990[12] 1990-2000[13] | |||

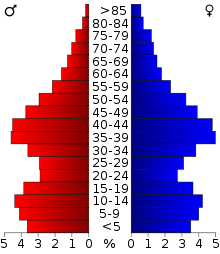

As of the census[14] of 2010, there were 222,209 people, 69,900 households, and 54,172 families residing in the city. The population density was 584.6 people per square mile (225.7/km²). There were 72,672 housing units at an average density of 213.3 per square mile (82.4/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 62.6% White, 29.8% Black or African American, 0.4% Native American, 2.9% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.2% from other races, and 3.0% from two or more races. 4.4% of the population were Hispanics or Latinos of any race. According to 2012 estimates 59.7% of the population is non-Hispanic white.

There were 69,900 households out of which 41.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.7% were married couples living together, 14.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 22.5% were non-families. 18.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 5.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.79 and the average family size was 3.17.

The age distribution was: 28.8% under the age of 18, 8.2% from 18 to 24, 32.3% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 9.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females there were 94.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $50,743, and the median income for a family was $56,302. Males had a median income of $39,204 versus $26,391 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,949. About 6.1% of families and 7.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.7% of those under age 18 and 9.0% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Top employers

According to Chesapeake's 2010 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[15] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chesapeake City Public Schools | 5,726 |

| 2 | City of Chesapeake | 3,167 |

| 3 | Chesapeake Regional Medical Center | 2,400 |

| 4 | LTD Hospitality Group | 2,185 |

| 5 | Sentara Healthcare | 1,400 |

| 6 | QVC | 1,276 |

| 7 | HSBC Finance | 1,200 |

| 8 | Cox Communications | 800 |

| 9 | Hewlett-Packard | 800 |

| 10 | Reliance Staffing | 700 |

| 11 | Lifetouch | 665 |

| 12 | Dollar Tree | 660 |

| 13 | Damco | 637 |

| 14 | General Dynamics Information Technology | 600 |

| 15 | Canon Information Technology Service | 572 |

| 16 | First Data | 500 |

Military

Chesapeake is home to two Navy bases:

- Northwest Annex, located in the Hickory area[16]

- NALF Fentress

Points of interest

Media

Chesapeake's daily newspaper is The Virginian-Pilot. Other papers include the Port Folio Weekly, the New Journal and Guide, and the Hampton Roads Business Journal.[17] Hampton Roads Magazine serves as a bi-monthly regional magazine for Chesapeake and the Hampton Roads area.[18] Hampton Roads Times serves as an online magazine for all the Hampton Roads cities and counties. Chesapeake is served by a variety of radio stations on the AM and FM dials, with towers located around the Hampton Roads area.[19] Chesapeake is also served by several television stations. The Hampton Roads designated market area (DMA) is the 42nd largest in the U.S. with 712,790 homes (0.64% of the total U.S.).[20] The major network television affiliates are WTKR-TV 3 (CBS), WAVY 10 (NBC), WVEC-TV 13 (ABC), WGNT 27 (CW), WTVZ 33 (MyNetworkTV), WVBT 43 (Fox), and WPXV 49 (ION Television). The Public Broadcasting Service station is WHRO-TV 15. Chesapeake residents also can receive independent stations, such as WSKY broadcasting on channel 4 from the Outer Banks of North Carolina and WGBS-LD broadcasting on channel 11 from Hampton. Chesapeake is served by Cox Communications which provides LNC 5, a local 24-hour cable news television network. DirecTV and Dish Network are also popular as an alternative to cable television in Chesapeake.

Infrastructure

Transportation

The growth of Chesapeake and its predecessors has been fueled by its location and transportation considerations. These continue to be major factors.

Funding for additional and replacement highways, bridges, and other transportation infrastructure is one of the major issues facing Chesapeake and much of the Hampton Roads region in the 21st century, as infrastructure originally built with toll revenues has aged without a source of funding to repair them or build replacements.

Tolls in Chesapeake are currently limited to the Chesapeake Expressway, but new ones may be imposed on some existing facilities to help generate revenue for transportation projects in the region.

Chesapeake is served by the nearby Norfolk International Airport in the City of Norfolk with commercial airline passenger service.

Within the city limits, Chesapeake Regional Airport is a general aviation facility located just south of Great Bridge. Also within the city, is the Hampton Roads Executive Airport located near Bowers Hill and the Hampton Roads Beltway. This airport caters to private airplane owners and enthusiasts. South of there, NALF Fentress is facility of the U.S. Navy and is an auxiliary landing field which is part of the large facility at NAS Oceana in neighboring Virginia Beach.

The Intracoastal Waterway passes through Chesapeake. Chesapeake also has extensive frontage and port facilities on the navigable portions of the Western and Southern Branches of the Elizabeth River.

The Dismal Swamp Canal runs through Chesapeake as well. The site of this canal was surveyed by George Washington, among others, and is known as "Washington's Ditch". It is the oldest continuously used man made canal in the United States today and has been in service for over 230 years. The canal begins in the Deep Creek section of the city branching off from the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River. The canal runs through Chesapeake paralleling U.S. Highway 17 into North Carolina and connects to Elizabeth City, North Carolina.

Five railroads currently pass through portions of Chesapeake, and handle some intermodal traffic at port facilities on Hampton Roads and navigable portions of several of its tributary rivers. The two major Class 1 railroads are CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern, joined by three short line railroads.

Chesapeake is located on a potential line for high speed passenger rail service between Richmond and South Hampton Roads which is being studied by the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation. A new suburban passenger station near Bowers Hill would potentially be included to supplement a terminal in downtown Norfolk.

Chesapeake is served by U.S. Highways 13, 17, 58, and 460. Interstate 64, part of the Hampton Roads Beltway, crosses through the city, Interstate 464 is a spur which connects it with downtown Norfolk and Portsmouth at the Berkley Bridge, and Interstate 664, which completes the Interstate loop from the Western Branch section of Chesapeake through the city of Newport News and into the city of Hampton.

State Route 168 is also a major highway in the area. It includes the Chesapeake Expressway toll road.

Chesapeake is the only locality in the Hampton Roads area with a separate bridge division. The city's Department of Public Works, Bridges and Structures division has 51 full-time workers. The city maintains 90 bridges and overpasses. Included are five movable span (draw) bridges which open an estimated 30,000 times a year for water vessels.[21]

Major highway bridges in Chesapeake include Steel Bridge, the Gilmerton Bridge, the Jordan Bridge, and the High Rise Bridge, all drawbridges crossing the Southern Branch Elizabeth River.

The Jordan Bridge was built in 1928 and operated with major weight restrictions. Motorists were charged a 75-cent toll that is used to pay for repairs. In 2008, the Jordan Bridge was closed for good. Replacing the bridge is now in progress with the center span having been removed. Construction is scheduled to begin Summer 2010 on a replacement bridge to be open by Fall of 2011. The new bridge is being privatlely funded just as the Jordon had been originally. Proposed tolls are in the 2 dollar range.

Although ten years newer, replacing the Gilmerton Bridge (built in 1938) on Military Highway is a more urgent need. A four-laned structure on a primary highway with much heavier traffic volume than the Jordan Bridge, the Gilmerton Bridge has suffered rust, cracked concrete and other problems. Much like the Jordan Bridge, the end of its useful life is also near. Replacing the Gilmerton Bridge has been a goal for Chesapeake for many years. In October, 2007, the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot reported that the city had accumulated $142 million in state and federal funding, enough to start building the replacement bridge some time in 2009.[21]

Hampton Roads Transit buses serve the city of Chesapeake as well as other cities in the Hampton Roads Area.

See also Transportation section of article Hampton Roads.

Utilities

Water and sewer services are provided by the city's Department of Utilities. Chesapeake receives its electricity from Dominion Virginia Power which has local sources including the Chesapeake Energy Center (a coal-fired and gas power plant), coal-fired plants in the city and Southampton County, and the Surry Nuclear Power Plant. Norfolk headquartered Virginia Natural Gas, a subsidiary of AGL Resources, distributes natural gas to the city from storage plants in James City County and in the city.

The Virginia tidewater area has grown faster than the local freshwater supply. Chesapeake receives the majority of its water from the Northwest River in the southeastern part of the city. To deal with intermittent high salt content, Chesapeake implemented an advanced reverse osmosis system at its Northwest River water treatment plant in the late 1990s. The river water has always been salty, and the fresh groundwater is no longer available in most areas. Currently, additional freshwater for the South Hampton Roads area is pumped from Lake Gaston, about 80 miles (130 km) west, which straddles the Virginia-North Carolina border along with the Blackwater and Nottaway rivers. The pipeline is 76 miles (122 km) long and 60 inches (1,500 mm) in diameter. Much of its follows the former right-of-way of an abandoned portion of the Virginian Railway.[22] It is capable of pumping 60 million US gallons (230,000 m3) of water per day. The cities of Chesapeake and Virginia Beach are partners in the project.[23]

The city provides wastewater services for residents and transports wastewater to the regional Hampton Roads Sanitation District treatment plants.[24]

Notable residents

- Clarence Clemons, musician

- Michael Cuddyer professional baseball player

- DeAngelo Hall, professional football player

- Alonzo Mourning,professional basketball player

- Jay Pharoah, comedian

- Chris Richardson, singer

- Ricky Rudd, NASCAR driver

- Mike Scott, professional basketball player

- Scott Sizemore professional baseball player

- Darryl Tapp, professional football player

- B. J. Upton, professional baseball player

- Justin Upton, professional baseball player

- Bubba Blackhawk Walters, 4 x World Kickboxing Champion

- David Wright, professional baseball player

- Ben Smith (CrossFit), 2015 CrossFit Games Champion

In popular culture

In 2015, in honor of the game's 80th birthday, Hasbro held an online vote in order to determine which cities would make it into an updated version of the Monopoly Here and Now: The US Edition of the game. Chesapeake, Virginia won the wildcard round, earning it a brown spot.[25]

See also

- Chesapeake City Public Schools

- Chesapeake Tribe

- List of famous people from Hampton Roads

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Chesapeake, Virginia

- Norfolk County, Virginia

References

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ . Virginia State 2013 Population Estimates Retrieved February 2, 2013

- ↑ "Chesapeake ranks on best cities list". WAVY.com. Retrieved 2012-01-11.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Eric Feber (11 April 2008). "Book on Chesapeake's history digs into city's boroughs". Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Chesapeake, Virginia Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ City of Chesapeake CAFR

- ↑ "Northwest Annex". navy.mil. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Hampton Roads News Links". abyznewslinks.com. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "Hampton Roads Magazine". Hampton Roads Magazine. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "Hampton Roads Radio Links". ontheradio.net. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ↑ Holmes, Gary. "Nielsen Reports 1.1% increase in U.S. Television Households for the 2006-2007 Season Archived July 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.." Nielsen Media Research. September 23, 2006. Retrieved on September 28, 2007.

- 1 2 "Shutdown of Jordan Bridge for repairs puts spotlight on problem". hamptonroads.com. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "Lake Gaston and Virginia Beach's Drinking Water". virginiaplaces.org. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Lake Gaston Water Supply Pipeline". www.vbgov.com. City of Virginia Beach. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "Hampton Roads Sanitation District". Hampton Roads Sanitation District. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ Mitchell, Becca (19 March 2015). "Virginia Beach, Chesapeake win spots on new Monopoly game board". wtkr.com. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

External links

- Chesapeake Conventions and Tourism

- City of Chesapeake

- Chesapeake Public Schools

- Hampton Roads Economic Development Alliance - serving Chesapeake

- Live streaming audio of Chesapeake Police Dept & Fire Dept.

Coordinates: 36°46′03″N 76°17′15″W / 36.767398°N 76.287405°W

|

City of Portsmouth and City of Norfolk |  | ||

| City of Suffolk | |

City of Virginia Beach | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Camden County, North Carolina and Currituck County, North Carolina |