Demographics of Virginia

The demographics of Virginia are the various elements used to describe the population of the Commonwealth of Virginia and are studied by various government and non-government organizations. Virginia is the 12th-most populous state in the United States with over 8 million residents[1] and is the 35th largest in area.[2]

Population

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 691,737 | — | |

| 1800 | 807,557 | 16.7% | |

| 1810 | 877,683 | 8.7% | |

| 1820 | 938,261 | 6.9% | |

| 1830 | 1,044,054 | 11.3% | |

| 1840 | 1,025,227 | −1.8% | |

| 1850 | 1,119,348 | 9.2% | |

| 1860 | 1,219,630 | 9.0% | |

| 1870 | 1,225,163 | 0.5% | |

| 1880 | 1,512,565 | 23.5% | |

| 1890 | 1,655,980 | 9.5% | |

| 1900 | 1,854,184 | 12.0% | |

| 1910 | 2,061,612 | 11.2% | |

| 1920 | 2,309,187 | 12.0% | |

| 1930 | 2,421,851 | 4.9% | |

| 1940 | 2,677,773 | 10.6% | |

| 1950 | 3,318,680 | 23.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,966,949 | 19.5% | |

| 1970 | 4,648,494 | 17.2% | |

| 1980 | 5,346,818 | 15.0% | |

| 1990 | 6,187,358 | 15.7% | |

| 2000 | 7,078,515 | 14.4% | |

| 2010 | 8,001,024 | 13.0% | |

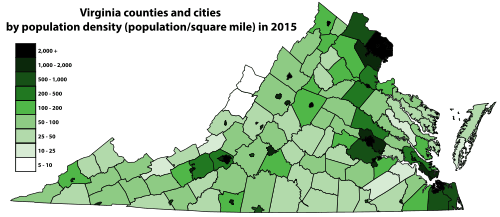

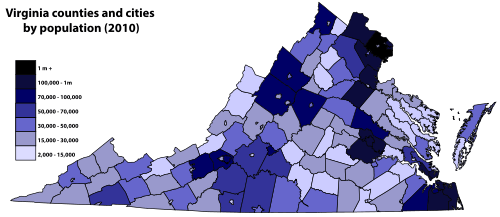

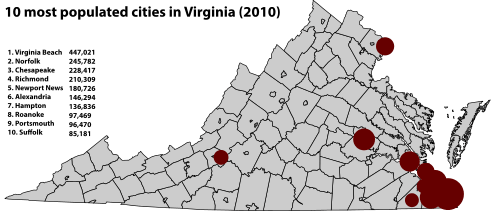

As of the 2010 United States Census, Virginia has a reported population of 8,001,024, which is an increase of 288,933, or 3.6%, from a previous estimate in 2007 and an increase of 922,509, or 13.0%, since the year 2000. This includes an increase from net migration of 314,832 people into the Commonwealth from 2000-2007. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 159,627 people, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 155,205 people.[3] Also in 2009, 6.7% of Virginia's population were reported as under five years old, 23.4% under eighteen, and 12.1% were senior citizens-65+.[4] The center of population of Virginia is located in Goochland County outside of Richmond.[5]

Ethnicity

| Ancestry | Percent |

|---|---|

| | 11.8% |

| | 11.0% |

| | 10.7% |

| | 10.0% |

| | 4.0% |

| | 2.1% |

| Subsaharan African | 2.0% |

| | 1.9% |

| | 1.9% |

| | 1.7% |

| | 1.0% |

| | 0.8% |

| | 0.7% |

| | 0.7% |

| | 0.6% |

| | 0.4% |

The five largest reported ancestry groups in Virginia are: African (19.6%), German (11.7%), American (11.4%), English (11.1%), and Irish (9.8%).[7] Most of those claiming to be of "American" ancestry are actually of English descent, but have family that has been in the country for so long, in many cases since the early seventeenth century, that they choose to identify simply as "American".[8][9][10][11][12] Many of Virginia's African population are descended from enslaved Africans who worked its tobacco, cotton, and hemp plantations. Initially, these slaves came from west central Africa, primarily Angola. During the eighteenth century, however, about half of them were derived from various ethnicities located in the Niger Delta region of modern-day Nigeria.[13] They contributed strongly to the development of Southern culinary arts, music, vernacular, architecture, and religion. With continued immigration to Virginia of other European groups and the 19th-century sales of tens of thousands of enslaved Africans from Virginia to the Deep South, the percent of enslaved Africans fell from once being half of the total population. By 1860 slaves comprised 31% of the state's population of 1.6 million.[14]

In colonial Virginia the majority of free people of color were descended from marriages or relationships of white men (servants or free) and black women (slave, servant or free), reflecting the fluid relationships among working people. Many free black families were well-established and headed by landowners by the Revolution.[15] From 1782 to 1818, a wave of slaveholders inspired by the Revolutionary ideals of equality freed slaves, until the legislature made manumissions more difficult. Some African Americans freed were those whose fathers were white masters, while others were freed for service.[16] By 1860 there were 58,042 free people of color (black or mulatto, as classified in the census) in Virginia.[14] Over the decades, many had gathered in the cities of Richmond and Petersburg where there were more job opportunities. Others were landowners who had working farms, or found acceptance from neighbors in the frontier areas of Virginia.[15]

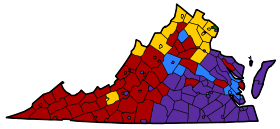

The twentieth-century Great Migration of blacks from the rural South to the urban North reduced Virginia's black population to about 20%.[4] Today, African-Americans are concentrated in the eastern and southern Tidewater and Piedmont regions where plantation agriculture was the most dominant.[17] The western mountains were settled primarily by people of heavily Scots-Irish ancestry.[18] There are also sizable numbers of people of German descent in the northwestern mountains and Shenandoah Valley.[19]

Because of recent immigration in the late 20th century and early 21st century, there are rapidly growing populations from Latin America, Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean, especially in Northern Virginia. Northern Virginia, which is a part of the DC metropolitan area, is one of the most diverse regions in the country. Virginia has one of the largest Salvadoran populations in the US, the vast majority of which is concentrated in Northern Virginia. Northern Virginia also has the largest Vietnamese population on the East Coast, with about 48,000 Vietnamese statewide as of 2007,[20] their major wave of immigration followed the Vietnam War.[21] The Hampton Roads area in southeastern Virginia, though it lags far behind Northern Virginia in diversity, is second in the state compared to other metro areas; aside from 'native' blacks and whites, the Hampton Roads only has large populations of Filipinos, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans. The Hampton Roads area has the highest percentage of Puerto Ricans of any metropolitan area in the Southern US outside Florida, and also has a sizable Filipino population with about 45,000 in the area, many of whom have ties to the U.S. Navy.[22] As of 2005, 6.1% of Virginians are Hispanic and 5.2% are Asian.[4] Their major wave of immigration followed the Vietnam War.[21] Virginia also continues to be home to eight Native American tribes recognized by the state, though all lack federal recognition status. Most Native American groups are located in the Tidewater region.[23]

| Virginia racial breakdown of population | Top ancestries by county | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial composition | 1990 | [24] 2000 | [25] 2010[26] |  | |||||

| White | 77.4% | 72.3% | 68.6% | ||||||

| Black | 18.8% | 19.6% | 19.4% | ||||||

| Asian | 2.6% | 3.7% | 5.5% | ||||||

| Native | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.4% | ||||||

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | – | 0.1% | 0.1% | American | English | Irish | |||

| Other race | 0.9% | 2.0% | 3.2% | | German | | African American | ||

| Two or more races | – | 2.0% | 2.9% | U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 special tabulation. American Factfinder provides census data and maps. | |||||

Languages

The Piedmont region is known for its dialect's strong influence on Southern American English. While a more homogenized American English is found in urban areas, various accents are also used, including the Tidewater accent, the Old Virginia accent, Appalachian English, and the anachronistic Elizabethan of Tangier Island.[27][28]

| Language | Percentage of population (as of 2010)[29] |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 6.41% |

| Korean | 0.77% |

| Vietnamese | 0.63% |

| Chinese (including Mandarin) | 0.57% |

| Tagalog | 0.56% |

| French | 0.46% |

| Arabic | 0.40% |

| German | 0.37% |

| Hindi | 0.34% |

| Persian | 0.32% |

As of 2010, 85.87% (6,299,127) of Virginia residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 6.41% (470,058) spoke Spanish, 0.77% (56,518) Korean, 0.63% (45,881) Vietnamese, 0.57% (42,418) Chinese (which includes Mandarin), and Tagalog was spoken as a main language by 0.56% (40,724) of the population over the age of five. In total, 14.13% (1,036,442) of Virginia's population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[29] English was passed as the Commonwealth's official language by statutes in 1981 and again in 1996, though the status is not mandated by the Constitution of Virginia.[30]

Religion

| Religion (2008) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Christian[31] | 76% | |

| Baptist | 27% | |

| Roman Catholic | 11% | |

| Methodist | 8% | |

| Lutheran | 2% | |

| Other Christian | 28% | |

| Judaism | 1% | |

| Islam | 2.6% | |

| Buddhism | 1% | |

| Hinduism | 1% | |

| Unaffiliated | 18% | |

Virginia is predominantly Christian and Protestant; Baptists are the largest single group with 27% of the population as of 2008.[31] Baptist denominational groups in Virginia include the Baptist General Association of Virginia, with about 1,400 member churches, which supports both the Southern Baptist Convention and the moderate Cooperative Baptist Fellowship; and the Southern Baptist Conservatives of Virginia with more than 500 affiliated churches, which supports the Southern Baptist Convention.[32][33]

Roman Catholics are the second-largest religious group, and the group which grew the most in the 1990s.[34][35] The Roman Catholic Diocese of Arlington includes most of Northern Virginia's Catholic churches, while the Diocese of Richmond covers the rest. The Virginia Conference is the regional body of the United Methodist Church. The Virginia Synod is responsible for the congregations of the Lutheran Church. The Episcopal Diocese of Virginia, Southern Virginia, and Southwestern Virginia support the various Episcopal churches. In November 2006, 15 conservative Episcopal churches voted to split from the Diocese of Virginia over its ordination of openly gay bishops and clergy; these churches continue to claim affiliation with the larger Anglican Communion through other bodies outside the United States. Though Virginia law allows parishioners to determine their church's affiliation, the diocese claims the secessionist churches' properties. The resulting property law case is a test for Episcopal churches nationwide.[36]

Presbyterians, Pentecostals, Congregationalists, and Episcopalians each composed 1–3% of the population as of 2001.[37] Among other religions, adherents of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints constitute 1.1% of the population, with 188 congregations in Virginia as of 2008.[38] Fairfax Station is home to the Ekoji Buddhist Temple, of the Jodo Shinshu school, the Sikh Foundation of Virginia a Sikh Gurdwara, and the Hindu Durga Temple. Chesapeake, Virginia is home to the Guru Nanak Foundation of Tidewater Sikh Gurdwara. While a small population in terms of the state overall, organized Jewish sites date to 1789 with Congregation Beth Ahabah.[39] Muslims are a rapidly growing religious group throughout the state through immigration.[40] Megachurches in the state include Thomas Road Baptist Church, Immanuel Bible Church, and McLean Bible Church.[41]

See also

References

- ↑ Resident Population Data. United States Census Bureau. 23 December 2010. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ↑ 2010 Census State Area Measurements and Internal Point Coordinates. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ↑ "State Resident Population—Components of Change: 2000 to 2007" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 2011-03-25. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Virginia - ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2009". United States Census Bureau. 2009. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ↑ "Population and Population Centers by State" (TXT). United States Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ↑ http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml American FactFinder, Community Facts, Virginia, Origins and Language, 2014 American Community Survey, Selected Social Characteristics (Household and Family Type, Disability, Citizenship, Ancestry, Language, ...)

- ↑ "Virginia - QT-P13. Ancestry: 2000". United States Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ↑ Sharing the Dream: White Males in a Multicultural America By Dominic J. Pulera.

- ↑ Reynolds Farley, 'The New Census Question about Ancestry: What Did It Tell Us?', Demography, Vol. 28, No. 3 (August 1991), pp. 414, 421.

- ↑ Stanley Lieberson and Lawrence Santi, 'The Use of Nativity Data to Estimate Ethnic Characteristics and Patterns', Social Science Research, Vol. 14, No. 1 (1985), pp. 44-6.

- ↑ Stanley Lieberson and Mary C. Waters, 'Ethnic Groups in Flux: The Changing Ethnic Responses of American Whites', Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 487, No. 79 (September 1986), pp. 82–86.

- ↑ Mary C. Waters, Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), p. 36.

- ↑ Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo (2005). Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- 1 2 "Census Data for Year 1860". Historical Census Browser. University of Virginia. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- 1 2 Heinegg, Paul (August 15, 2007). "Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware". Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ Nicholls, Michael; Lenaye Howard (May 15, 2007). "Notes of Manumission: Selected Virginia Counties, ca.1782-1818". Utah State University. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ "Regional Differences in Race & Ethnicity". University of Virginia. January 8, 2007. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ↑ "Scots-Irish Sites in Virginia". Virginia Is For Lovers. January 3, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ↑ Bly, Daniel W. (2002). From the Rhine to the Shenandoah (Volume III ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Gateway Press, Inc.

- ↑ "Virginia - Selected Population Profile in the United States (Vietnamese alone)". United States Census Bureau. 2007. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- 1 2 Wood, Joseph (January 1997). "Vietnamese American Place Making in Northern Virginia". Geographical Review. Geographical Review, Vol. 87, No. 1. 87 (1): 58–72. doi:10.2307/215658. JSTOR 215658.

- ↑ Firestone, Nora (June 12, 2008). "Locals celebrate Philippine Independence Day". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ↑ Schulte, Brigid (November 23, 2007). "As Year's End Nears, Disappointment". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The United States, Regions, Divisions, and States".

- ↑ "Population of Virginia: Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts".

- ↑ "2010 Census Data".

- ↑ Clay III, Edwin S.; Bangs, Patricia (May 9, 2005). "Virginia's Many Voices". Fairfax County, Virginia. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ↑ Miller, John J. (August 2, 2005). "Exotic Tangier". National Review. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- 1 2 "Virginia". Modern Language Association. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ↑ Joseph 2006, p. 63

- 1 2 "American Religious Identification Survey". Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture. 2008. Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- ↑ Vegh, Steven G. (November 10, 2006). "2nd Georgia church joins moderate Va. Baptist association". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ "SBCV passes 500 mark". Baptist Press. November 20, 2007. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ "U.S. Religion Map and Religious Populations" (PDF). The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. September 11, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- ↑ "State Membership Report (1990–2000 Change)". Association of Religion Data Archives. 2000. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- ↑ Boorstein, Michelle (November 14, 2007). "Trial Begins in Clash Over Va. Church Property". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ↑ "Key Findings". American Religious Identification Survey. 2001. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ "USA-Virginia". Country Profiles. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2008. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ↑ Olitzky, Kerry M.; Raphael, Marc Lee. The American Synagogue: A Historical Dictionary and Sourcebook, Greenwood Press, June 30, 1996, p. 359.

- ↑ Alfaham, Sarah (September 11, 2008). "Muslims' visibility in region growing". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Charlottesville Daily Progress. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ↑ "Megachurch Search Results". Hartford Institute for Religion Research. 2008. Retrieved November 7, 2008.