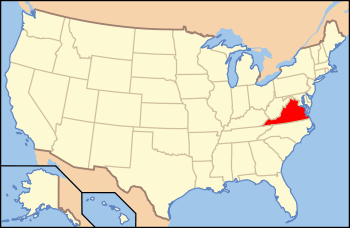

Mason House (Guilford, Virginia)

|

Mason House | |

|

Mason House in 1960 | |

| |

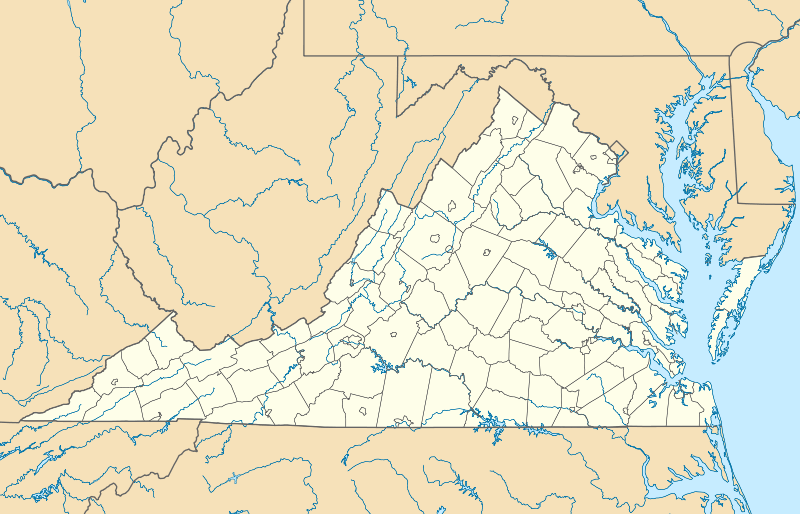

| Location | VA 615, Guilford, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°50′1″N 75°39′14″W / 37.83361°N 75.65389°WCoordinates: 37°50′1″N 75°39′14″W / 37.83361°N 75.65389°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | c. 1722 |

| Built by | Andrews, William |

| Architectural style | Colonial, Jacobean-Georgian |

| NRHP Reference # | 74002100[1] |

| VLR # | 001-0029 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 21, 1974 |

| Designated VLR | September 17, 1974[2] |

Mason House, also known as the Hinman-Mason House, is an historic dwelling located at Guilford in Accomack County, Virginia.[3] Trees were cut for its construction in the winter of 1729/30 and construction likely started soon thereafter.[4] The house is a single story, single-pile, three-bay, brick structure. The mason hired to construct it laid its brickwork in an extraordinary fashion, which reflects its early date. He set glazed brick headers in large chevron patterns in recessed panels between the front windows and door. He seemed also to have raised the chimneys as exterior features, but they were demolished and rebuilt as interior stacks in the 19th century. To date no archaeological evidence for their original form have been found.

Timber work in the house is as unusual as the brickwork. The carpenter raised the roof in common rafter pairs with rafters set flat, as is typical of early work. He spiked the rafters to a tilted false plate. While one would expect these details, the setting of the false plate directly over the brick wall is unusual. The reason for this alignment of the false plate allows for kick rafters, common to late 17th and early 18th century buildings, and for a boxed cornice, the latter quite unusual for country dwellings in the Chesapeake at this date. This is the earliest recorded tilted false plate in the mid-Atlantic states that includes a boxed cornice.

The carpenter then covered the roof with weatherboards to act as sheathing for wooden shingles that were pegged (instead of nailed) in place. Dormers which survived until recently date to the late 18th century, reportedly replacing wider ones thought to have been part of the original construction.

Original mantels do not survive, but window frames, sash, door trim and the staircase do. In general, the trim is spare but distinctive. At least one door architrave used on the ground floor includes a wide plane that transitions to the adjoining plaster wall with a cyma in a manner uncharacteristic of typical Georgian-era work. Similar architraves were used at Larkin's Hundred, a ca. 1740 dwelling in Anne Arundel County Maryland, and in the original 1740s wing of Myrtle Grove in Talbot County on Maryland's Eastern Shore. The joiner built the stair as a closed string, with heavy, symmetrically-turned balusters set over a skirt board finished as an Ionic entablature complete with a pulvinated frieze. A large, molded newel post is reminiscent of late 17th-century work in England and its handrail, molded in the form of early Georgian work, is quite large in cross section. The rail and molded treads are made of oak.

Partitions between first-floor rooms are of frame construction. That between the passage and the "hall" was originally insulated for sound with "filling"—a clay material packed between the wall studs. The baseboard was installed and painted black (with some of the paint slopping onto the filling) before the wall was plastered. Widely-spaced riven lath was then nailed to the studs to help to bind the plaster to the walls. Such widely-spaced plaster lath, while uncommon in the period, is nevertheless frequently discovered on the Shore, most recently at Grape Valley (1742), nearby in Birdsnest.

The house is an early example of one laid out with a center passage. A parlor (or master bedchamber) and hall flank the passage on the ground floor. Two chambers flank the passage in the attic. A frame wing was added in the late 19th century.

Researchers at Colonial Williamsburg discovered a handmade paint brush used during original construction as a wedge to prop the front wall plate in position. Masons then sealed it when they plastered the interior wall, attesting to its date of insertion. Paint analysis by Susan Buck demonstrates that despite its crudity it had been used to coat something with a paint that included hand-ground Prussian blue pigments, making it the earliest recorded use in America.[5]

It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.[1]

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ↑ Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission (July 1974). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Mason House" (PDF). Commonwealth of Virginia, Department of Historic Resources. and Accompanying photo

- ↑ Report by Herman J. Heikkenen, Architectural Research Files, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. See also Cary Carson and Carl R. Lounsbury, The Chesapeake House: Architectural Investigation by Colonial Williamsburg, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013

- ↑ See report in files, Department of Architectural Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

External links

- Hinman-Mason House, Guilford, Accomack County, VA: 23 photos, 5 measured drawings, and 4 data pages at Historic American Buildings Survey