Upland South

The terms Upper South and Upland South refer to the northern part of the Southern United States, in contrast to the Lower South or Deep South.

Geography

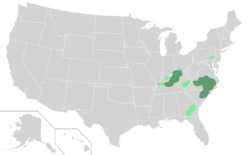

There is a slight difference in usage between the two terms.[1] "Upland South" is usually defined based on landforms, generally referring to the southern Appalachian Mountains or Appalachia (although not the full region defined by the Appalachian Regional Commission), the Ozarks and Ouachita Mountains, and the plateaus, hills, and basins between the Appalachians and Ozarks, such as the Cumberland Plateau, part of the Allegheny Plateau, the Nashville Basin, and the Bluegrass Basin, among others. The southern Piedmont region is often considered part of the Upland South, while the Atlantic Coastal Plain (the Chesapeake region and Carolina's Lowcountry) is generally not.[2]

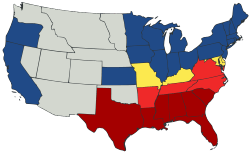

In contrast, the term "Upper South" tends to be defined politically by state. The term dates to the early 19th century and the rise of the Lower South, which became noted for its differences from the more northerly parts of the American South. In antebellum times, the term Upper South generally referred to the Slave states north of the Lower or Deep South.[3] During the American Civil War era, the term Upper South was often used to refer specifically to the Confederate states that did not secede until after the attack on Fort Sumter — Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas. This can also include the border states of Kentucky, Missouri, West Virginia, Maryland, or Delaware in the Upper South.[4] Today, although many definitions are still based on Civil War-era politics, the term Upper South is often used for all of the American South north of the Deep South.

The Encyclopædia Britannica defines the Upper South as the states of North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky, and West Virginia. The Upland South is defined by landforms rather than states but encompasses the same general region. The Upper/Upland South is also described in the Encyclopædia Britannica as the "Yeoman South", in contrast to the "Plantation South".[5]

These two definitions cover the same general area. The Upland South, not being defined by state lines, includes parts of Lower South states, such as northwestern South Carolina (the Upstate), North Georgia, North Alabama (and, in some definitions, Central Alabama), and eastern Oklahoma. It also includes parts of some Northern states, such as Southern Illinois (the Shawnee Hills), Southern Indiana, and Southern Ohio. Sometimes northeastern Mississippi and western Maryland are included as well. In the same way, the Upland South usually does not include parts of some Upper South states, such as the Mississippi embayment (which includes eastern Arkansas, the Missouri Bootheel, the Purchase area of Kentucky, and part of West Tennessee), and the coastal lowlands of North Carolina and Virginia.

Despite these differences, the two terms, Upland South and Upper South, refer to the same general region — the northern part of the American South — and are frequently used synonymously. The corresponding terms, Lower South and Deep South, similarly refer to the same general region to the south of, and lower in elevation, than the Upland or Upper South. Likewise, the terms Lower South and Deep South are often used interchangeably.

History and culture

The Upland South differs from the Deep South in several significant ways; terrain, histories, economics, demographics, and patterns of settlement.

Origins

The Upland South emerged as a distinct region in the late 18th century and early 19th century. Migration and settlement patterns from colonial coastal regions into the interior had been established for many decades, but the scale grew dramatically toward the end of the 18th century. The general pattern was a westward migration from the lowcountry and Piedmont regions of Virginia, North Carolina, and Maryland, as well as a southwestern migration from Pennsylvania. Large numbers of European immigrants arrived in Philadelphia and followed the Great Wagon Road west and south into the Appalachian Highlands, via the Great Appalachian Valley. These migration streams from Virginia and Pennsylvania resulted in the Shenandoah Valley becoming well-settled as early as 1750. The early settlers of the Ohio Valley were mainly Upland Southerners.[6] Much of the culture of the Upland South originated in southeastern Pennsylvania and spread down the Shenandoah Valley.[7]

These migration streams eventually spread through Appalachia and westward through the Appalachian Plateau region into the Ozarks and Ouachitas, and ultimately contributed to the settlement of the Texas Hill Country.[8] The main ethnicities of these early settlers included English, Scots-Irish, Scottish, and German.[9] The early culture of the Upland South was influenced by other European ethnicities. For example, the Swedes and Finns of New Sweden — relatively few in number but pioneering Pennsylvania before the Germans and Irish arrived — contributed techniques of forest pioneering such as the log cabin, the "zig-zag" split-rail fence, and frontier methods of shifting cultivation such as girdling trees and using slash and burn to convert forest into temporary crop and pasture land.[10]

The pattern of settlement that had begun in the Appalachian foothills was continued and extended through the mountains and highlands to the west and across the Mississippi River into the Ozark highland region. Where there was the danger of Indian attacks, people settled at first in clustered "stations", but as danger lessened settlement tended to be in a rural, dispersed, kin-structured pattern, with relatively few towns and cities. These early settlers of the Upland South tended to practice small-scale farming, stock raising, and hunting. This settlement pattern of the Upland South was markedly different from the Deep South and the Midwest.

A significant portion of the 19th century settlers of the Midwest were from the Upland South. The southern Midwest was most heavily settled by Upland Southerners, especially in Missouri, southern Indiana and southern Illinois.[7] This early migration to the southern Midwest included many African Americans. They were mainly freed slaves, but slavery was permitted in some places such as St. Louis, under the Missouri Compromise of 1820. In the mid 19th century there were concentrations of African Americans in east-central Indiana, southwest Michigan, and elsewhere.[7] Due to their early settlement of the Midwest, Upland Southerners initially controlled territorial and state governments, and played a major role in establishing the political and social culture, such as the Black Laws of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.[7] Over the 19th century the percentage of Upland Southerners fell, especially as large numbers of native born Midwesterners joined the population.[7]

Distinct from neighboring regions

The Deep South is generally associated historically with cotton. By 1850 the term "Cotton States" was in common use and the differences between the Deep South (lower) and Upland South (upper) recognized. A key difference was the Deep South's plantation-style cash crop agriculture (mainly cotton, rice, sugar), using African American slaves working large farms while plantation owners tended to live in towns and cities. This system of plantation farming was originally developed in the West Indies and introduced to the United States in South Carolina and Louisiana, from where it spread throughout the Deep South, although there were local exceptions wherever conditions did not support the system. The sharp division between town and country, the intensive use of a few cash crops, and the high proportion of slaves, all contrasted with the Upland South. Virginia and its surrounding region stands out as different from both the Upland South and the Deep South. Its history predates the West Indian plantation model, and while tobacco was a cash crop from the start, and African slaves became widely used, Virginia did not share many of the Deep South's characteristics, such as the early proliferation of towns and cities.[11]

As a result of the difference in the use of slaves, the boundary between the Upland South and Deep South can still be seen today on maps showing the population percentage of African-Americans. The term Black Belt originally referred to a region of black soil in Alabama that was especially good for cotton farming (the Black Belt of Alabama), but has become more commonly used today to refer to the region of the South with a high percentage of African-Americans. In contrast, the Upland South was less involved with slavery from the start.

In addition, the Cotton Belt of the Deep South was controlled by Indians (mainly the Five Civilized Tribes of the Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole) powerful enough to keep pioneering settlers from moving into the region. The Deep South's cotton boom did not occur until after the Indians were forced west in the early 19th century. In contrast, the Upland South, Kentucky and Tennessee especially, were the scene of Indian resistance and pioneering settlement in the late 18th century. Thus the Upland South was already colonized and had established its particular settlement patterns before most of the Deep South was opened to general colonization.

The differences between the Upland South and lowlands of the South's Atlantic Seaboard and cotton belt often resulted in regional tension and conflict within states.[12] For example, during the late 18th century, the upland "backcountry" of North Carolina grew in population until the Upland Southerners there outnumbered the older, well-established, wealthier coastal populations. In some cases the conflict between the two resulted in warfare, such as War of the Regulation in North Carolina.[12] Later, similar processes resulted in divergent populations in states to the west. Northern Alabama, for example, was settled from Tennessee by Upland Southerners, while southern Alabama was one of the core regions of the Deep South cotton boom. During the American Civil War some areas of the Upland South were noted for their resistance to the Confederacy. The uplands of western Virginia became the state of West Virginia as a result, though half the counties of the new state were Secessionist, and partisan warfare continued throughout the war.[13] Kentucky and Missouri remained in the Union but were torn by internal strife. The southern Appalachian region of East Tennessee, parts of western North Carolina and some parts of northern Alabama and northern Georgia were widely noted for their pro-Union sentiments.

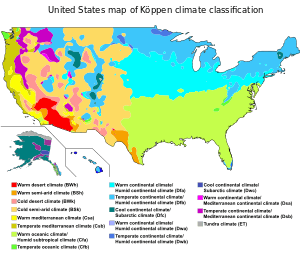

The two regions also differ physically. The upland south is dominated by deciduous hardwood forest, in contrast to the Deep South's predominantly evergreen pine forests. The upland south is often much hillier than the deep south, due to the Deep South being part of the coastal plain.

Today

The Upland South contains its own sub-regions. The fertile lowlands of the Nashville Basin and the Bluegrass Basin gave rise to the truly urban cities of Nashville and Lexington, which grew into banking and mercantile centers in the 19th century, home to an elite class of Upland Southerners, including bankers, lawyers, and politicians. Most of the Upland South, however, remained rural in character.

Although historically very rural, the Upland South was one of the nation's early industrial regions and continues to be today. Mining of coal, iron, copper, and other minerals has been part of the region's economy since the 18th century. As early as 1750 lead and zinc were mined in Wythe County, Virginia, and copper was mined and smelted in Polk County, Tennessee. Two major Appalachian goldfields were developed, the first in western North Carolina beginning in 1799. By 1825 Rutherford County was the center of the nation's most extensive gold mining. In 1828 a much richer Gold Strike was made in north Georgia, mostly within what was then the territory of the Cherokee Nation. The mining camp of Dahlonega boomed during the ensuing Georgia Gold Rush. Iron foundries in Virginia and early coal mining operations in central Appalachia date to before 1850.[14] Furnaces and forges were built in the Appalachians of north central Alabama as early as 1818. Some were fueled with nearby deposits of bituminous coal. Similar examples of early urban-industrial areas include Embree's Iron Works in East Tennessee (1808), the Red River iron region of Estill County, Kentucky (1806-8), and the Jackson Iron Works near Morgantown, West Virginia (1830). Wheeling, West Virginia was known as "Nail City" in the 1840s and 1850s. By 1860 Tennessee was the third largest iron producing state in the nation, after Pennsylvania and New York.[15] The scale of mining, especially coal mining, increased dramatically after 1870.[16] The importance of mining and metallurgy can be seen in the many towns with names such as Pigeon Forge and Bloomery (a bloomery being a type of smelting furnace), scattered across the Upland South.

Logging has also been an important part of the Upland South's economy. The region became the United States' primary source of timber after railroads allowed large scale industrial logging in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Today, the historic importance of the Upland South's forests can be seen in its many national forests, such as Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee, Nantahala National Forest in North Carolina, and Daniel Boone National Forest in Kentucky, among many others. The Upland South's terrain and forests, as well as history and culture, occur in parts of states usually associated with the Midwest and Deep South. These areas are often associated with national forests, for example Mark Twain National Forest in southern Missouri, Shawnee National Forest in southern Illinois, Hoosier National Forest in southern Indiana, Wayne National Forest in southeast Ohio, William B. Bankhead National Forest in northern Alabama, Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest in northern Georgia, Sumter National Forest in South Carolina, and Ouachita National Forest in Arkansas and Oklahoma.

Textile mills and industry have been an important factor in the Upland South's economy since the time of the Deep South's cotton boom.

Today the Upland South contains a diversity of people and economics. Some parts, like the Shenandoah Valley, are famous for their rural qualities, while other parts, like the Tennessee Valley, are heavily industrialized. Knoxville and Huntsville are both centers of industry and scientific research.

As a cultural region

The Upper South today remains a culture region, with distinct ancestry,[18] dialect,[19] cuisine, religion[20] and other characteristics. The heavily rhotacized Upland Southern dialect still predominates in much of West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and the western portions of North Carolina, Maryland, and Virginia. Noticeable influence can even be found in parts of Deep South states such as northern Georgia and northern Alabama and parts of the southern portions of Missouri as far north as St. Louis, Indiana, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. Like the Deep South, the region is heavily evangelical Protestant with Baptists making up a plurality in the vast majority of counties. The cuisine of the Upper South is generally closely related to the lowland south, excluding southern low-country areas in which the cuisine tends to involve seafood and rice, which are not common in the Upper South. Tobacco is still a large crop in Kentucky and North Carolina.

See also

References

- ↑ Hudson, John C. (2002). Across this Land: A Regional Geography of the United States and Canada. JHU Press. pp. 101–116. ISBN 978-0-8018-6567-1.

- ↑ The origin and evolution of the Upland South is explored in Meinig (1986), pp. 158, 386, 449

- ↑ Meinig (1993), pg. 293.

- ↑ Davidson, James West. Nation of Nations: a History of the American Republic. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2008. Print. (according to the glossary of the textbook)

- ↑ "Britannica Library". Library.eb.com. Retrieved 2015-08-11.

- ↑ Turner, Frederick Jackson (1921). The Frontier in American History. Holt. pp. 164–166.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sisson, Richard; Christian K. Zacher; Andrew Robert Lee Cayton (2007). The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press. pp. 196–198. ISBN 978-0-253-34886-9.

- ↑ Meinig (1998), pg. 224

- ↑ Drake (2001), pp. 36-38, describes these early pioneer ethnic groups and notes that the term "Scotch-Irish" (Scots-Irish), while predominately Presbyterian northern Irish, also included a significant number of Catholic southern Irish; and that the term "English" was a general catch-all term including ancestries such as French Huguenot (John Sevier's family, for example). On the topic of colonial Catholic Irish immigration, see also Williams (2002), pp. 43-44.

- ↑ Williams (2002), pg. 104

- ↑ For Antebellum differences between the Upper South and Lower South, see Meinig (1998) pp. 222-224

- 1 2 Turner, Frederick Jackson (1921). The Frontier in American History. Holt. pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Weigley, Russell F., A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861-1865, Indiana Univ. Press, 2000, pg. 55

- ↑ Drake, Richard B. (2003). A History of Appalachia. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-8131-9060-0.

- ↑ Williams, John Alexander (2002). Appalachia: A History. University of North Carolina Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8078-5368-9.

- ↑ "Readings - A Short History Of Kentucky/Central Appalachia | Country Boys | FRONTLINE". PBS. Retrieved 2015-08-11.

- ↑ Archived March 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived March 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Map 2" (GIF). Ling.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2015-08-11.

- ↑ Archived May 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

Bibliography

- Drake, Richard B. A History of Appalachia. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8131-2169-8.

- Jordan-Bychkov, Terry G. The Upland South: The Making of an American Folk Region and Landscape. Harrisonburg: U of Virginia P, 2003. ISBN 1-930066-08-2.

- Meinig, D. W. The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, Volume 1: Atlantic America, 1492–1800. New Haven: Yale University Press: 1986. ISBN 0-300-03882-8.

- Meinig, D. W. The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, Volume 2: Continental America, 1800–1867. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-300-05658-3.

- Meinig, D. W. The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, Volume 3: Transcontinental America, 1850–1915. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-300-08290-8.

- Meinig, D. W. The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, Volume 4: Global America, 1915–2000. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-300-10432-4.

- Williams, John Alexander. Appalachia: A History. Charlotte: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8078-5368-2.

- Zelinsky, Wilbur. The Cultural Geography of the United States. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall, 1973.