William W. Belknap

| William Worth Belknap | |

|---|---|

| |

| 30th United States Secretary of War | |

|

In office October 25, 1869 – March 2, 1876 | |

| President | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Preceded by | John Aaron Rawlins |

| Succeeded by | Alphonso Taft |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

September 22, 1829 Newburgh, New York |

| Died |

October 12, 1890 (aged 61) Washington, D.C. |

| Political party |

Democratic Republican |

| Spouse(s) |

Cora LeRoy Carrie Tomlinson Mrs. John Bower |

| Alma mater | Princeton University |

| Profession |

General; Lawyer Politician;Author |

| Military service | |

| Service/branch |

United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands | 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

William Worth Belknap (September 22, 1829 – October 12, 1890) was a lawyer, soldier in the Union Army, government administrator in Iowa, and the 30th United States Secretary of War. Although Belknap served with distinction in the Civil War, his tenure as President Grant's Secretary of War was controversial, with Belknap accused of indirectly selling weapons to France while the United States was ostensibly neutral during the Franco-Prussian War, and accepting illicit kickbacks in exchange for making a tradership appointment; traders received exclusive rights to sell goods at U.S. military posts, making the appointments lucrative and highly sought after. The trader post scandal led to Belknap's resignation, impeachment by the House, and trial by the Senate during the summer of 1876.

A native of New York, Belknap graduated from Princeton University in 1848, studied law with a Georgetown attorney, and passed the bar in 1851. He then moved to Iowa, where he practiced law in partnership with Ralph P. Lowe. Belknap entered politics as a Democrat and was elected to the Iowa House of Representatives in 1857. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Belknap joined the Union Army; a veteran of the Iowa Militia who had attained the rank of captain, he was commissioned as a major in the 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry. He took part in numerous engagements, including Shiloh and Corinth, served as a regimental, brigade, division, and corps commander, and served in high-level staff positions. In hand-to-hand combat at the Battle of Atlanta, Belknap captured a wounded Confederate commander. By the end of the war, Belknap had been promoted to brigadier general of volunteers, and received a brevet promotion to major general.

Belknap declined a regular Army commission after the war, and was appointed Iowa's Collector of Internal Revenue by President Andrew Johnson; he served for four years without controversy. In 1869, President Grant appointed Belknap Secretary of War. As secretary, Belknap requisitioned portraits for all the previous Secretaries of War, intending to create a complete collection for display in honor of the United States Centennial. He also aided Chicago Fire victims in 1871 and pardoned James Webster Smith, the first African American cadet to attend the United States Military Academy, who had been expelled after falsely being accused of misconduct. During the Reconstruction Era, Belknap's War Department and the U.S. military worked under supervision of President Ulysses S. Grant and the United States Attorney General's office to vigorously enforce the mandates of Reconstruction upon the defeated South. In 1875, Grant, Belknap, and other members of Grant's administration secretly agreed to remove troops from the Black Hills after gold was discovered. The Black Hills were protected by the military because they had been guaranteed to the Lakota by treaty; allowing a gold rush of white settlers to take place enabled the United States to gain de facto possession after the Lakota refused to sell.

A Congressional investigation in 1876 revealed that Belknap had received kickbacks in return for a lucrative contract. Starting in 1870, Belknap took the payments to support the lavish lifestyle common among senior officials in Washington D.C.; after the death of his second wife, his third wife and he continued the practice. When his crime was discovered in 1876, Belknap resigned as Secretary of War, hoping to head off an effort to impeach him in the U.S. House of Representatives. Grant had accepted his resignation before the House voted; despite his resignation, the House impeached him, and he was tried by the Senate. Belknap was acquitted when the Senate vote failed to achieve the required two-thirds majority; several senators believed they had the power to convict an incumbent cabinet secretary, but not one who had left office. Belknap's political reputation was permanently damaged while his wife and daughters abandoned him. Belknap resumed practicing law in Washington and remained popular among Iowa Civil War veterans. He died of a heart attack in 1890.

Belknap's legacy is that of both notable virtues and flaws. He was commended for bravery during the Civil War, but while Secretary of War he undermined the military careers of William Tecumseh Sherman and Oliver Otis Howard. He preserved Mathew Brady's photographic history of the American Civil War, provided speedy aid to victims of the Great Chicago Fire, enforced Grant's Reconstruction policy, and started the National Weather Service. However, he accepted illegal payments in order to live a lavish lifestyle at the expense of soldiers who relied on military trading posts, and permitted white settlers to overrun the Black Hills after they had been promised to the Lakota people by treaty. Additionally, until Grant explicitly told to him to stop, Belknap attempted to prevent completion of America's first steel cantilever bridge by arbitrarily changing the design specifications to include expensive, unnecessary modifications. He pursued this effort at the request of Mississippi River steamboat operators who feared a loss of traffic to railroads that would use the new Eads Bridge; Belknap was alleged to have accepted payments from the steamboat companies in exchange for his actions. After he left office in disgrace, the War Department experienced unprecedented turmoil, going through a succession of four Secretaries of War within a 13-month period.

Early life and career

_(US_Army_Brigadier_General).jpg)

William Worth Belknap was born on September 22, 1829 in Newburgh, New York to career soldier William G. Belknap, who had fought with distinction in the War of 1812 and the Mexican American War.[1] His mother was Anne Clark Belknap.[2] In 1848, Belknap graduated from Princeton University.[1] After graduation, Belknap studied law with Georgetown attorney Hugh E. Caperton. After an examination by Judge William Cranch in 1851, Belknap was admitted to the bar, moved to Keokuk, Iowa, and entered into a partnership with Ralph P. Lowe.[1] In 1854, Belknap had a home built in Keokuk. He served in the Iowa House of Representatives as a Democrat from 1857 to 1858.[1][3] After moving to Keokuk, Belknap joined a local militia company, the City Rifles, and he attained the rank of captain.

Marriages and family

Belknap was married three times. The first was in 1854 to Cora LeRoy who died in 1862.[4] Belknap married Carita S. Tomlinson of Kentucky in January, 1869;[4] she died of tuberculosis shortly after childbirth in December, 1870.[4] Belknap married again on December 11, 1873, this time to Amanda Tomlinson Bower, his second wife's sister and the widow of John Bower.[4] With his first wife he was the father of Hugh R. Belknap, U.S. Representative from Illinois. With his third wife he had one daughter, Alice Belknap, born November 28, 1874.[5][6][7] She was considered one of Washington society's most sought after belles.[8] In 1897 she reportedly converted to Judaism for her engagement with Paul May, an attaché of the Belgian legation in Washington,[9][10] however, the much gossiped-about engagement was broken the following year, and Alice Belknap eventually married William Barklie Henry of Philadelphia in June 1898.[11][11]

American Civil War

When the American Civil War started, Belknap, a Democrat loyal to the Union, joined the Union Army in the Autumn of 1861 and was commissioned a major in charge recruiting the 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry on December 7.[1][12] Belknap, a tall, charismatic and handsome man, was naturally suited to the rigors of being a soldier; he was an effective recruiter, and because of his militia experience he was proficient at training newly enlisted recruits.[13]

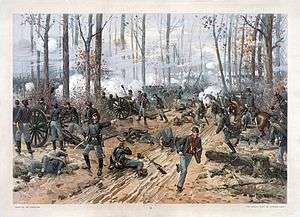

Shiloh, Corinth, and Vicksburg

In March 1862, Maj. Belknap and the 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry were finally mustered into military action.[13] Traveling by steamer from St. Louis, Belknap was sent to the front at the Battle of Shiloh; arriving at Pittsburgh Landing on April 6 joining the Army of the Tennessee, under authority of Union General Ulysses S. Grant.[13] Belknap and his men were ordered to the front to serve under Maj. Gen Benjamin M. Prentiss at the Hornet's Nest.[13] Belknap and his raw 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry troops were forced to fight like regular army veterans on Prentiss depleted line.[13] Belknap fought bravely, was slightly wounded, and his horse was shot and killed from under him.[13] After Shiloh, Belknap served as acting commander of the 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry at the Battle of Corinth.[13] Col. Hugh T. Reid, commander of the 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry, had been severely injured in the neck at Shiloh and removed from active duty.[14] Col. Reid stated that at Shiloh Belknap, "was always in the right place at the right time, directing and encouraging officers and men as coolly as a veteran"[2] At Corinth, Belknap was noted for his "conspicuous gallantry".[2] After Corinth, Belknap and the 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry for a time served on guard duty.[13][14] Belknap was formerly promoted from Major to Lieutenant Colonel on August 20, 1862.[12] Belknap was promoted from Lieutenant Colonel to Colonel of the Iowa 15th Volunteer Infantry on June 3, 1863.[12][13] Belknap's primary military operation took place at the Siege of Vicksburg until July 4, 1863.[1][13] On December 24, 1863 Belknap was in command of the 11th Iowa Volunteer Infantry and the 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry reinforcing Redbone, Mississippi, south of Vicksburg.[14] On February 26, 1864 Belknap served as Provost Marshall of Post in Canton, Mississippi.[14]

Battle of Atlanta and March to the Sea

On June 8, 1864 Col. Belknap and the veteran 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry were transferred to the 4th Division, XVII Corps at Ackworth, Georgia.[13] On July 22, 1864 at the Battle of Atlanta, Belknap served with distinction, fighting against the 45th Alabama Infantry.[1][15] Belknap and his Iowa troops dug in and set up earthworks and a parapet around Bald Hill.[15] The 45th Alabama infantry led by Confederate Col. Harris D. Lampley, assaulted the entrenched Union line two times but were repelled by massive Union gun power.[15] On the second time, Lampley and his remaining men crossed over into the Union line to do hand-to-hand combat. Lampley, who had been shot, cursed his men who had fallen or were retreating.[15] In the midst of the fierce fighting the burly Belknap grabbed the wounded Lampley by the collar, spun him around and shouted, "Look at your men ! They are dead ! What are you cursing them for !?" [16] The wounded Lampley was captured and held as a Union prisoner of war until his death on August 24.[15]

On July 28, 1864 Col. Belknap was in charge of the 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry and the 32nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry having reinforced Maj. Gen. R.L. Smith's XV Corps.[14] On July 30, Belknap was promoted to Brigadier General and given command of the 4th Division, XVII Corps, and participated in Major Gen. Sherman's operations in Georgia and the Carolinas.[1][14] After Atlanta was taken by the Union Army, Belknap accompanied Maj. Gen. Sherman on his March to the Sea.[1] Belknap was promoted Brevet Major General on March 13, 1865 as a reward for his bravery in the Atlanta Campaign.[1] On August 24, 1865, Brevet Maj. Gen Belknap was mustered out of the U.S. Army.[1]

Iowa Collector of Internal Revenue (1865-1869)

In 1865, after the American Civil War had ended, President Andrew Johnson appointed Belknap, now retired from military service, to the post of Iowa Collector of Internal Revenue. In that position, Belknap was responsible for collecting millions of dollars in federal taxes.[17] Belknap served in that position for four years, until he was appointed Secretary of War by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1869.[4] During his term as Collector, Belknap associated himself with the Republican Party in the period of Reconstruction.[12]

Secretary of War (1869-1876)

30th U.S. Secretary of War

Huntington 1874

On the advice of General of the Army William T. Sherman, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Belknap to Secretary of War on October 25, 1869, to take the place of Secretary John A. Rawlins who had died in office earlier of tuberculosis.[18] Belknap at that time was a protégé of Sherman's, having fought in the Atlanta Campaign and accompanied him on Sherman's March to the Sea.[18] President Grant believed Belknap had served capably during the American Civil War and deserved to head the War Department.[18] After his appointment, Belknap imposed or recommended several positive initiatives. He recommended that Congress act to fix the date of May 1 as the start of the fiscal year. He inaugurated the preparation of historical reports by post commanders, and proposed actions to preserve Yellowstone National Park.[19] Not all of Belknap's actions were well received, however. He initiated a protocol that bypassed and weakened the authority of General of the Army Sherman. Subsequently, in 1874, Sherman left Washington D.C. and moved his headquarters to St. Louis.[20] Major General Oliver O. Howard was also ostracized by Belknap. While stationed in Oregon, in 1874, Major General Howard candidly expressed his opinion of Belknap. Howard stated that Belknap was deceptive to "General Grant", that Belknap was not a true Republican, and that he associated nightly with "foul-mouthed" Democratic Kentucky associates. Howard also opined that Belknap was "not in favor" of the President's Indian Peace policy.[21] That statement is likely related to a conflict, during Belknap's tenure, between the U.S. War Department and the U.S. Department of Interior as to which Department would control the destiny of American Indians.[20] In the context of this era, Belknap's actions may not be seen as overtly aggressive or overreaching. In terms of Reconstruction, historian Jean Edward Smith, notes that Grant, former General of the Army, supervised the use of the U.S. military and that Belknap "had less freedom of action then other cabinet members."[22]

Belknap and his respected wives, Carlita and Amanda, lived a lavish lifestyle entertaining Washington society in grand manner in their fashionably appointed home.[23] Publicly, Belknap's private life was uneventful having kept a low profile while other scandals were discovered during Grant's second term in office.[23] It was not until an 1876 House investigation into the War Department that Belknap was publicly associated by corruption.[23]

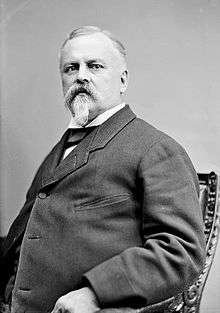

War Department portrait gallery 1869

Upon assuming office in 1869, Belknap conceived an idea to make a series of portraits of previous civilian heads of the War Department in honor of the then upcoming 1876 U.S. Centennial.[24] Belknap hired renowned artists Daniel Huntington, Robert Weir, and Henry Ulke and had them paint portraits of the long list of his predecessors in the War Department.[24] Belknap's own portrait was painted by Daniel Huntington in 1874.[24] The Secretary of War portraits were then assembled into a distinct collection to be viewed by the public.[24] The portrait painting of the Secretary of War was continued by Belknap's successors.[24] In addition to secretaries, portraits were made of other persons notable for their war conduct distinction.[24] Belknap has been given "unqualified credit" for his creation of the War Department gallery in Washington D.C.[24]

Trader post monopolies 1870

In 1870, Belknap lobbied Congress, and on July 15 was granted the sole power to appoint and license sutlers with ownership rights to highly lucrative "traderships" at U.S. military forts in the Western frontier.[17][25] The power to appoint traderships by the Commanding General of the Army, at that time being William T. Sherman, was repealed.[25] Having been granted the sole power to appoint traderships, Belknap further empowered those traderships with a virtual monopoly. Soldiers stationed at forts with Belknap appointed sutlers could only buy supplies through the authorized tradership.[17] These monopoly traderships were considered good investments during the Gilded Age.[26] Soldiers on the Western frontier, who were thus forced to buy supplies at higher than market prices, were left destitute as a result.[27] Hostile American Indians bought supplies at these traderships, including high-quality breech-loaders and repeating rifles.[28] Soldiers, however, were requisitioned by Belknap's War Department inferior breech-loaders that jammed on the third round.[28] The policy affected the firepower of the U.S. troops and may have contributed to the defeat of Col. Custer and the 7th Cavalry at Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876.[28] Custer, however, had refused for unclear reasons to bring Gatling guns with the ability to shoot 150 rounds per minute, that would have strongly increased his regimental fire power.[29]

In 1870, Belknap's second wife, Carita, successfully lobbied her husband to appoint a New York contractor (Caleb P. Marsh) to a trader post at Fort Sill located in the Indian Territory.[30] John S. Evans, however, had already been appointed to that position.[30] To settle the question of ownership, regarding the tradership, an illicit partnership contract, authorized by Belknap, was drawn. The contract allowed Evans to keep the tradership at Fort Sill, provided that he pay $12,000 of the annual profits to Marsh. Evans would be allowed to keep the remaining profits.[30] Marsh, in turn, was required to split half of his receipts from the contract, $6,000 per year, with Carita. However, Carita only received one payment before her death (tuberculosis after childbirth) in 1870. After Carita's death, Marsh continued to pay Belknap Carita's share of the profits, for the benefit of her child.[30] Although the child died in 1871, Belknap continued to accept quarterly kickback payments from Marsh.[30] When Belknap remarried, to Carita's sister, Amanda, both Belknap and Amanda continued to accept the quarterly payments from Marsh.[30]

French arms sales 1870

During the Franco-Prussian War that lasted from 1870 to 1871, the United States declared neutrality.[31] Belknap had been criticized and accused by Grant Administration critics, Senator Charles Sumner and Senator Carl Schurz, for violating neutrality and selling arms to French agents.[31] Belknap sold obsolete U.S. War Department firearms to a neighbor of the Remington family. Samuel Remington, as arms-selling agent to the French Government, subsequently arranged the sale of those firearms to France.[31][32] Belknap subsequently sold 54,000,000 cartridges to the French Army that would specifically fit the firearms he had previously sold to the Remington neighbor.[31] A Congressional investigation which took place in 1872 exonerated Belknap, and no criminal charges for impeachment were initiated.[31]

Pardoned Cadet Smith 1871

During the Reconstruction Era, in 1870, former slave James Webster Smith, through private sponsorship, became the first African American cadet to enroll at West Point.[33] Smith, however, was immediately and severely hazed by white cadets. It is believed that the Academy's military establishment was determined to force Smith out.[34] One of Sec. Belknap's nephews, a cadet at the Academy, had been reprimanded (but not otherwise punished) for hazing Smith.[35] In one instance, Smith was arrested and taken to a military court for fighting a white cadet. However, Major General Oliver O. Howard, an advocate for African American civil rights and in charge of the trial, acquitted Smith of all charges and gave him a light punishment for unruly conduct.[36] This outraged the Academy's Bureau of Military Justice, who made a formal protest to Belknap on November 20, 1870.[37] In a second instance in January 1871, Smith was arrested again for not holding his head up when marching, after being severely harassed by white cadets.[37] This time Smith was convicted and his case was appealed to Belknap.[37] Smith was pardoned by Belknap and allowed to return to West Point as a plebe.[37] In 1874, Smith continued at West Point, until, Prof. Peter S. Michie, a white supremacist, gave Smith a private test, in defiance of traditional West Point practice.[38] Smith was forced out of West Point after having failed the test and was denied a retest by Michie.[38] Ironically, Belknap believed Smith had been shown more favor than white cadets at West Point.[38] Major General Thomas H. Ruger, appointed Superintendent of West Point in 1871, reduced the amount of hazing of cadets by 1873 and made strong efforts to eradicate the "discreditable" practice.[39] Belknap admired Ruger's performance as West Point Superintendent and stated, "I am pretty satisfied with the success of your management, and private conversations with officers of all grades, & with civilians too, who have been there since your accession..."[40][41] Other African Americans followed Smith's entrance into West Point and Henry O. Flipper became the first to graduate from the Academy in 1877.[42] Smith was finally commissioned an officer by West Point in 1997, one hundred and twenty three years later.[43]

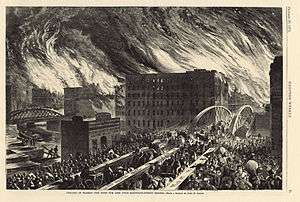

Aided Chicago fire victims 1871

From October 8, 1871 to October 10 a devastating fire burned and destroyed much of Chicago. The fire killed hundreds of people and caused $200,000,000 in damages. Over 100,000 citizens were left destitute and homeless.[44] Belknap, concerned for the victims, promptly took action on October 9 and sent food rations from St. Louis, tents from Jeffersonville for the many homeless persons, and two company troops from the Omaha infantry to keep peace and order.[44] On October 10, Belknap in writing a dispatch to Lt. General Philip Sheridan stated that the fire was "...a national calamity. The sufferers have the sincere sympathy of the nation."[44] Belknap ordered military officers around the nation to send supplies to Chicago "liberally and promptly".[44]

New Orleans street riot 1872

During Reconstruction Grant enforced civil and voting rights for African Americans in the South, using the army and newly created Justice Department to destroy the Ku Klux Klan in 1871, under the Enforcement Acts. Louisiana during Reconstruction was one of the most politically turbulent and disputed states. Rival political factions fought for power in the state government, requiring the deployment of federal troops to keep peace.[45] During January 1872, the War Department was kept on high alert, concerned with the potential for violent confrontation, in New Orleans, between Gov. Henry Clay Warmoth's faction and former speaker of the Louisiana House, George W. Carter's faction.[46] Warmoth supported social equality and voting rights for African Americans, but southern conservatives considered him a corrupt northern carpetbagger.[47] To prevent disorder Major General William H. Emory, Louisville District Commander, in charge of New Orleans, decided that federal troops were needed to prevent violence.[48] Belknap at the War Department informed General in Chief William T. Sherman and supported Emory's request for the use of federal troops.[48] On January 5, federal troops were deployed in New Orlean to prevent violence until the 11th.[49] Sec. Belknap advised President Grant that Emory was the best man on the scene to make the decision to use military force.[49] On the 9th a street riot broke out after a Gov. Warmoth supporter was assassinated; Gov. Warmoth's state police retaliated by attacking and dispersing Carter's faction at the Gem Saloon; Emory deployed reinforcement troops on the 10th to restore order.[50] On January 12, Grant, wanting to stay out of state politics, told the mayor of New Orleans through the War Department that martial law would not be declared in Louisiana.[50] An angry mob of thousands of Carter's men took to the streets. Emory deployed troops equipped with Gatling guns.[51] Carter's men dispersed knowing Emory would use U.S. military force to keep the peace.[51] On January 15, Grant wrote to Belknap that he desired to prevent the "danger of bloodshed" without having to take sides with any two factions.[52] On January 16, Att. Gen. George H. Williams told Gov. Warmoth, that Grant would only take sides if there was a "clear case of legal right and overruling necessity."[52] On January 22, as both Gov. Warmoth and Carter formed rival militias and the two were ready for war, President Grant issued orders through the War Department for Emory to use troops if necessary.[53] When Emory communicated Grant's message to both Gov. Warmoth and Carter, the two rival factions dispersed and a 10-month peace was kept.[53]

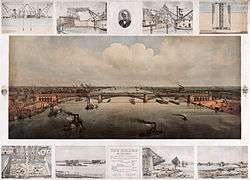

Eads steel bridge commission 1873

In 1873, the construction of the America's first steel arched bridge, named after James B. Eads, was nearing completion in St. Louis.[54] Belknap, under influence from the Keokuk Packet steamliner company, was opposed to its completion. He desired the bridge torn down, so steamers would not have to lower their smoke stacks to go under the bridge.[54] Belknap created a commission to either destroy and rebuild the bridge to allow steamers to go under, or to build a canal around the bridge for steamers to pass.[54] Eads, who was friends with Grant, visited Washington D.C. in November 1873 before Belknap submitted the report to Congress, and asked that Grant rescue the bridge from destruction.[55] Belknap stated he had the authority to keep the rivers from being obstructed according to federal law.[55]

President Grant reminded Belknap that Congress had authorized the construction of the bridge.[55] President Grant was convinced that Congress would not authorize money to tear the bridge down, overruled Belknap's decision, and told Belknap in person "You certainly cannot destroy this structure on your own authority...General, you had better drop this case." [56] Belknap was embarrassed, stood up blushing, bowed to President Grant, and left the meeting.[56] The Eads Bridge was completed in 1874 and is still in active use today.[57]

Yellowstone expedition 1875

During the summer of 1875, Sec. Belknap decided to explore Yellowstone the nation's first national park, signed into law by President Grant on March 2, 1872.[58] Accompanying Sec. Belknap were Col. Randolph B. Marcy, Lt. Col. James W. Forsyth, and Chicago businessman William E. Strong.[58] Leading the expedition was Lt. Gustavus C. Doane, who had led the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition in 1870, the first extensive federal survey of the Yellowstone territory, that was responsible in part for the formation of Yosemite National Park.[58][59] Lt. Doane left Fort Ellis, where he was stationed, and made preparations for Sec. Belknap's party arrival at Mammoth Hot Springs.[60] On July 26, Sec. Belknap's party reached Fort Ellis and proceeded to meet Lt. Doane at Mammoth Hot Springs.[60] Led by Lt. Doane, Belknap's party attempted to retrace the original 1870 Expedition in addition to hunting for any big game found on the journey.[61] Sec. Belknap's party included 24 soldiers and two ambulances.[62] The two-week expedition proved to be troublesome as Lt. Doane was unable to find big game to hunt and after briefly viewing the Grand Canyon of Yellowstone Sec. Belknap's party had to wait several hours before Lt. Doane finally found the trail.[61][63]

Great Sioux War 1876

In late July 1874 a U.S. Army expedition under Col. George A. Custer discovered gold in the Black Hills.[64] Soon many miners trespassed on Indian land under the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie to mine for gold. In June 1875, President Grant attempted to resolve the problem by offering Indians $100,000 per year to lease their land or $6,000,000 for the Black Hills.[64] The Lakota Sioux under Chief Red Cloud refused since the offer would require the Sioux to be moved to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma. On November 3, 1875, as the crisis escalated, President Grant held a secret meeting at the White House including Belknap and Secretary of Interior Zachariah Chandler. Grant, Belknap, and Chandler agreed to a plan that would withdraw U.S. troops from the Black Hills, allowing miners to mine on Indian Territory.[64] The purpose of troop withdrawal was to start an Indian War.[64] On December 3, 1875 Chandler ordered all Indians to return to their respected reservations, however, militant Indians under Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse refused to return. By January 1876 4,000 miners illegally occupied Indian land.[64] When hostile Indians refused to leave their hunting grounds by the January 31 deadline, Chandler turned the Indians over to Belknap's War Department stating "the said Indians are hereby turned over to the War Department for such action on the part of the Army as you [Belknap] may deem proper under the circumstances."[65] On February 8, 1876 Generals Crook and Terry were ordered to start winter military campaigns against hostile Indians and the Great Sioux War commenced.[66] On March 1, 1876 Crook, in freezing weather, marched north from Fort Fetterman near Douglas, Wyoming to attack Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse and their Indian followers on the Powder River.[67] The following day, March 2, Belknap abruptly resigned office over the Fort Sill traderpost scandal. From March 3 to March 7 the War Department was run ad interum under Grant's appointed Secretary of Navy George M. Robeson. On March 8, 1876 Alphonso Taft was appointed by Grant Secretary of War. The Great Sioux War ended in April 1877 under President Rutherford B. Hayes.

House investigation, corruption, and resignation 1876

On February 29, 1876, during the Great Sioux War, upon rumors that Belknap was receiving profits from traderships, Representative Hiester Clymer launched an investigation into the War Department.[68] Although Clymer and Belknap were friends, Clymer was an extreme partisan Democrat who strongly opposed Republican Reconstruction and supported white supremacy. The U.S. Army during Belknap's tenure was used in combination with the Justice Department to prosecute the Ku Klux Klan, a policy strongly opposed by the Democratic Party. The Democrats had gained control of the House and were looking for a scandal that would aid them in winning the 1876 elections. Caleb P. Marsh testified to the Clymer Committee that Belknap had personally taken Fort Sill tradership profit payments in exchange for a tradership partnership agreement between Marsh and Fort Sill sutler John S. Evans.[68] On March 1, Belknap and his counsel went before Clymer's committee, however, Belknap declined to testify.[68] In a White House meeting on March 2, Belknap appeared before President Grant, who asked for Belknap's resignation.[68] Earlier that morning, Treasury Secretary Benjamin Bristow had told President Grant of Belknap's impending impeachment.[68] President Grant accepted Belknap's resignation at 10:20 A.M.[68] Clymer's committee was informed of Belknap's resignation at 11:00 A.M.[68] Although Belknap's resignation caused great commotion among House members, it did not forestall action by the Clymer committee. The committee unanimously passed resolutions to impeach Belknap and drew up five articles of impeachment to be sent to the Senate.[68] Belknap, by then a private citizen, was impeached by a unanimous vote of the House of Representatives.[69] Speaker of the House Michael C. Kerr wrote to the Senate that Belknap resigned "with intent to evade the proceedings of impeachment against him."[70] Belknap's case was constitutionally unprecedented and would serve as reference for nine other civilian officials resignations before trial, including President Richard Nixon.[71]

On March 29, and April 4, 1876 Col. George Custer testified before the Clymer Committee that continued to gather evidence for the Senate trial. Custer's testimony was a sensation because he accused Grant's brother and Secretary of War of corruption. Although Belknap had resigned he had many political allies in Washington D.C. to protect him.

Upon Belknap's sudden resignation in March, Grant had to hastily ask his Secretary of Navy George M. Robeson to run the War Department ad interum, which lasted a week. Grant then appointed Alphonso Taft Secretary of War; Taft was an attorney and former judge; unfamiliar with military matters, he reluctantly agreed to serve in order to stabilize the War Department, and Grant promised to nominate him later for another, more suitable position. In May, Grant kept his word when he created a vacancy in the Attorney General's post by naming the incumbent, Edwards Pierrepont, to serve as Minister to England; he then appointed Taft to serve as Attorney General, and J. Donald Cameron to succeed Taft as Secretary of War. Cameron was a prominent Republican, and the son of Senator Simon Cameron, who had served as President Abraham Lincoln's Secretary of War during the Civil War. J. Donald Cameron could expect easy Senate confirmation because of his father's influence; in addition, raising his profile by serving in the cabinet helped facilitate Simon Cameron's plan to have his son succeed him in the Senate, which happened less than a year later.

Senate trial and acquittal

Starting on April 5, 1876, Belknap was tried by the Senate, presided over by Supreme Court Chief Justice Morrison Waite. For several weeks Senators argued whether the Senate had jurisdiction to put Belknap on trial since he already resigned office in March.[72] Belknap's defense managers argued that the Senate had no jurisdiction to put Belknap on trial.[72] The Senate, however, had ruled by a vote of 37-29 that it had jurisdiction to impeach Belknap, despite his resignation in March.[73][72] Twenty-five out of 60 Senators voted Belknap's acquittal of the charges on technical grounds keeping the Senate from convicting Belknap by the required two-thirds majority.[74][72][72] All Senators agreed that Belknap took the money from Marsh. Twenty-three of the senators who voted for Belknap's acquittal believed that the Senate did not have jurisdiction.[74] [72] Grant's speedy acceptance of Belknap's resignation undoutedly saved Belknap from conviction.[74] After the trial Belknap was abandoned by his wife Amanda, known as "Puss" in Washington society, and his daughters who traveled to and remained in Europe.[72]

Washington D.C. indictment

After his Senate acquittal, Belknap was indicted by a grand jury on August 1, 1876, and set for trial in the District of Columbia federal court.[75] However, the district courts were unlikely to convict for any crimes that involved less than $47,000.[75] Washington D.C. District Attorney Henry H. Wells, who was in charge of the Belknap case, was advised by Attorney General Alphonso Taft, upon President Ulysses S. Grant's instructions, that the evidence against Belknap would not sustain a conviction in court and that Belknap had suffered enough during the Senate trial.[76] On February 8, 1877, Belknap's case, indictment No. 11,262, was dismissed by Justice Arthur MacArthur Sr.[76]

Later career

Belknap moved to Philadelphia, having been disgraced by the Senate trial, but later returned to Washington to resume the practice of law. Belknap, his reputation damaged, never returned to hold political office, although he remained popular among his fellow Iowa Civil War veterans. During the 1880 presidential race Belknap was lampooned in a political cartoon against the candicacy of Ulysess S. Grant's third term presidential bid for office. Belknap was portrayed as a corrupt associate to Grant. In 1887, Belknap coauthored the book History of the Fifteenth Regiment, Iowa Veteran Volunteer Infantry.

Death, burial, and memorial

_Control_IAS_76007700.jpg)

Front

Belknap died suddenly from a massive heart attack in Washington, D.C. on Sunday October 12, 1890.[1] The New York Times stated his death occurred on Sunday between 1:00 A.M and 9:00 A.M., having died alone, at his residence in the Evans building on New York Avenue.[1][77] Prior to his death, Belknap had played cards with his friends on Saturday night, then retired upstairs for the evening.[1][77] Belknap's wife, Amanda, was in New York City at the time.[77] At 8:30 A.M. on Monday morning, Belknap's business associate, John W. Cameron, picked up Belknap's mail on the first floor of Belknap's home and business residence and proceeded to the second floor where Belknap lived.[1] Cameron and a maid found that all the rooms had been locked.[1] A janitor was summoned to open the doors, and a step ladder was used to peer into Belknap's bedroom.[1] Belknap had placed his hat and coat on a chair and his lifeless body was found on his bed.[1] Belknap's left arm had been raised toward his head with his left hand tightly clenched.[1] Belknap's bed clothes were disheveled and he appeared to have struggled for breath.[1] The physician who initially examined Belknap's body stated Belknap had died of apoplexy, however, an autopsy by the coroner revealed that Belknap had suffered heart disease.[1][78] The War Department was notified and received with "genuine sorrow" Belknap's death, since Belknap had been a popular Secretary of War.[77]

Belknap was buried in Section 1 at Arlington National Cemetery on October 16, 1890. The ceremony was conducted by St. John's Episcopal Church.[79] The site features a granite gravestone with a bronze relief memorial designed by sculptor Carl Rohl-Smith. The bronze relief (2 ft. x 2 ft.) bust shows Belknap wearing a dress uniform with his hair parted on the proper right side as well as a long, full beard. The relief is placed on the front of a granite base (6 ft. x 5 ft. x 5 ft.). This piece was surveyed by the Smithsonian's Save Outdoor Sculpture! survey in 1995 and its condition was described as treatment being needed. The relief is signed by the artist: C.R. 1897.[80]

A plaque on the front of the granite base is inscribed:

- BORN 1829 - DIED 1890

- COLONEL 15TH IOWA VOL. INFANTRY

- BRIGADIER & BREVET MAJOR GENERAL U.S.VOLS.

- SECRETARY OF WAR 1869-1876

- ERECTED BY HIS COMRADES OF THE

- CROCKER IOWA BRIGADE

- 11TH, 13TH, 15TH AND 16TH IOWA VOL. INFANTRY

- ARMY OF THE TENNESSEE.

- COMPANIONS OF THE MILITARY ORDER OF THE

- LOYAL LEGION OF THE UNITED STATES

- AND OTHER FRIENDS [80]

Historical reputation

In 2003 biographer Edward S. Cooper described Belknap as a man of virtues and flaws.[81] According to Cooper, Belknap "willing turned to graft to support the social ambitions of his wives" while living a lavish lifestyle in Washington D.C. at the expense of soldiers and Indians during the Gilded Age.[82] Belknap is positively credited by Cooper for creating and expanding the weather bureau, reforming the military justice system, and for preserving Mathew Brady's photographic record of the Civil War.[81] Belknap's abrupt and controversial resignation in March 1876 caused an unprecedented succession of four Secretaries of War within a 13-month time period: Belknap, Alphonso Taft, J. Donald Cameron, and George W. McCrary.

Indian campaigns, battles, and wars under Secretary Belknap

- Comanche Campaign (1867-1875)

- Marias Massacre (1870)

- Camp Grant massacre (1871)

- Modoc War (1872-1873)

- Battle of Salt River Canyon (1872)

- Battle of Turret Peak (1873)

- Red River War (1874-1875)

- Second Battle of Adobe Walls (1874)

- Bates Battlefield (1874)

- Battle of Palo Duro Canyon (1874)

- Great Sioux War (1876-1877) Note: Although the Great Sioux War began in February 1876 under Belknap's tenure, no significant battles were fought between the beginning of the war and up to his sudden resignation in March. The war, lasting until April 1877, took place under five cabinet secretaries. Four under President Grant: Belknap, George M. Robeson (ad interum), Alphonso Taft, and J. Donald Cameron, and one under President Rutherford B. Hayes, George W. McCrary.

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- Gen. William Worth Belknap House, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in Iowa

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 New York Times (October 14, 1890), Belknap's Sudden Death

- 1 2 3 Dictionary of American Biography (1936), William Worth Belknap

- ↑ Agency, Iowa Legislative Services. "State Representative".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Koster (2010), pp. 59-60.

- ↑ Patterson, Michael Robert. "William Worth Belknap, Brigadier General, United States Army".

- ↑ "The History of Lee County, Iowa: Containing a History of the County, Its Cities, Towns, Etc". Western Historical Company. 1 January 1879 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Grimmett, Richard F. (1 January 2009). "St. John's Church, Lafayette Square: The History and Heritage of the Church of the Presidents, Washington, DC". Hillcrest Publishing Group – via Google Books.

- ↑ Form: An Illustrated Weekly Pub. Every Sat. in the Interests of American Society at Home and Abroad

- ↑ http://www.jpress.nli.org.il/Olive/APA/NLI_heb/SharedView.Article.aspx?parm=EuuTlq9n%2FuTn9uWsoKJaYMq5i%2FLuEWYz6Om3wxk5HKgdyNhIOmJbGr1hhjrsuI%2B7Yw%3D%3D&mode=image&href=HZV%2F1897%2F07%2F09&page=4&rtl=true

- ↑ "The Capital". Capital Publishing Company. 1 January 1897 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 "The Capital". Capital Publishing Company. 1 January 1898 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 4 Arlington National Cemetery

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Ingersoll (1880), pp. 566-577

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Belknap-Tyler (1887), p. 609

- 1 2 3 4 5 Severance (2012), Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Alabama in the Civil War, p. 213

- ↑ Belknap-Tyler (1887), p. 24

- 1 2 3 Koster (2010), p. 59

- 1 2 3 Smith (2001), pp. 542-543

- ↑ Bell (1981), p. 78

- 1 2 Donovan (2008), pp. 104-105

- ↑ Simon ( 2003), The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Vol. 5, 1874

- ↑ Smith (2001), p. 543

- 1 2 3 Purcell 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bell (1981), p. 8

- 1 2 Forty First Congress, Statutes At Large, pp. 319-320

- ↑ Koster, p. 59-60

- ↑ Koster pp. 58-59

- 1 2 3 Koster, p. 58

- ↑ Hofling (1981), p. 30

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McFeely (1981), p. 58

- 1 2 3 4 5 McFeely (1981), pp. 150-151

- ↑ Doukas (2003), p. 80

- ↑ McFeely (1981), p. 375

- ↑ McFeely (1981), pp. 375-376.

- ↑ McFeely (1981), p. 377

- ↑ McFeely (1981), pp. 377-378

- 1 2 3 4 McFeely (1981), p. 378

- 1 2 3 McFeely (1981), p. 379

- ↑ New York Times (August 23, 1873), The Military Academy Report of the Board of West Point Visitors

- ↑ Cowan's (June 24, 2009), West Point Superintendent Thomas H. Ruger Archive

- ↑ Belknap (Nov. 17, 1871), Frohne's Historic Military

- ↑ Art of the Possible Online (July 3, 2009), James Webster Smith and Henry O. Flipper Archived November 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Reading Eagle, Armies First Black Cadet Gets Bars 123 Years Later, p. A13

- 1 2 3 4 New York Times (October 11, 1871), The Ruined City

- ↑ Coakley (1988), pp. 316-317

- ↑ Coakley (1988), pp. 317-318

- ↑ Hogue (2006), Uncivil War, pp. 58-59

- 1 2 Dawson (1982), pp. 117-118

- 1 2 Coakley (1988), pp. 318-319

- 1 2 Coakley (1988), p. 319

- 1 2 Coakley (1988), pp. 319-320

- 1 2 Coakley (1988), p. 320

- 1 2 Coakley (1988), pp. 321-322

- 1 2 3 Stevens (2008), pp. 99-100

- 1 2 3 Stevens (2008), pp. 100-101

- 1 2 Stevens (2008), pp. 101-102

- ↑ Eads Bridge infosite, en.structurae.de; accessed June 19, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Scott (2007), p. 105

- ↑ Cambell (1909) , p. 72

- 1 2 Scott (2007), pp. 105-106

- 1 2 Bonney, Orrin H. (1970). Battle Drums and Geysers-The Life And Journals Of Lt. Gustavus Cheyney Doane, Soldier And Explorer Of The Yellowstone And Snake River Regions. Chicago: Swallow Press. pp. 47–50.

- ↑ Scott (2007), p. 106

- ↑ Scott (2007), pp. 106-107

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jeffrey Ostler (2004) The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee, pp 60-62

- ↑ Secretary of the Interior to the Secretary of War, February 1, 1876, National Archives

- ↑ Colonel Drum to Gen. Terry and Gen. Crook, February 8, 1876, National Archives

- ↑ Collins, Jr., Charles D. Atlas of the Sioux Wars, Second edition, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2006, Map 14, 15

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 McFeely (1981), pp. 151-152

- ↑ Hinds (1907), section 2444, pp. 903-904.

- ↑ Hinds (1907), section 2454, p. 922.

- ↑ Woldow (Feb. 2004), Vermont Law Library Newsletter

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Purcell 2008, p. 34.

- ↑ Hinds (1907), section 2459, p. 934.

- 1 2 3 McFeely (1974), p. 152

- 1 2 New York Times (August 02, 2012), Acquittal of Belknap

- 1 2 New York Times, The Suit Against Gen. Belknap

- 1 2 3 4 The Milwaukee Journal, Dying A Solitary Death

- ↑ Spokane Falls Review, Death Of General Belknap

- ↑ M.R. Patterson (2003). "William Worth Belknap". Arlington National Cemetery Website. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- 1 2 Smithsonian (1995). "William Worth Belknap Monument, (sculpture).". Save Outdoor Sculpture. Smithsonian. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- 1 2 Cooper (2003) William Worth Belknap: An American Disgrace, p 13

- ↑ Cooper (2003) William Worth Belknap: An American Disgrace, pp 12-13

Sources

Books

- Belknap, William W.; Tyler, Loren S. (1887). William W. Belknap, ed. History of the Fifteenth Regiment, Iowa Veteran Volunteer Infantry. Keokuk, Iowa: R.B. Ogden & Son, Print.

- Cooper, Edward S. (2003). William Worth Belknap: an American disgrace. Cranbury, New Jersey: Rosemont Publishing & Printing Corp. ISBN 0-8386-3990-9.

- Coakley, Robert W. (1988). Davis S. Trask, ed. The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1789-1878. Army Historical Series. Washington D.C.: Center of Military History United States Army.

- Dawson III, Joseph G. (1982). Army Generals and Reconstruction: Louisiana, 1862-1877. Louisiana State University: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-1960-0.

- Hofling, Charles K. (1981). Custer and the Little Big Horn: A Psychobiographical Inquiry. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1814-2.

- McFeely, William S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, LTD. ISBN 0-393-01372-3.

- Purcell, L. Edward (2008). David Hudson, Marvin Bergman, Loren Horton, eds. The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 1-58729-685-3.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- Donovan, James (2008). A Terrible Glory: Custer and the Little Bighorn. New York, New York: Little, Brown, and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-15578-6.

Articles

- Koster, John (June 2010). "The Belknap Scandal Fulcrum to Disaster". Wild West: 58–64.

Newspapers

- "Belknap's Sudden Death" (PDF). New York Times. New York, New York. October 14, 1890. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

Dictionaries

- Rossiter Johnson, ed. (1906). Biographical Dictionary of America Belknap, William Worth. Boston: American Biographical Society. pp. 280–281.

- Dictionary of American Biography William Worth Belknap. New York, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1936.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Belknap, William Worth". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Belknap, William Worth". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Worth Belknap. |

- Belknap biography, history.army.mil

- William Worth Belknap at Find a Grave.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Aaron Rawlins |

U.S. Secretary of War Served under: Ulysses S. Grant 1869–1876 |

Succeeded by Alphonso Taft |