Angiotensin II receptor antagonist

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists, also known as angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), AT1-receptor antagonists or sartans, are a group of pharmaceuticals that modulate the renin–angiotensin system. Their main uses are in the treatment of hypertension (high blood pressure), diabetic nephropathy (kidney damage due to diabetes) and congestive heart failure. They block activation of angiotensin II AT1 receptors, preventing angiotensin II from binding there.

Medical uses

Angiotensin II receptor blockers are used primarily for the treatment of hypertension where the patient is intolerant of ACE inhibitor therapy. They do not inhibit the breakdown of bradykinin or other kinins, and are thus only rarely associated with the persistent dry cough and/or angioedema that limit ACE inhibitor therapy. More recently, they have been used for the treatment of heart failure in patients intolerant of ACE inhibitor therapy, in particular candesartan. Irbesartan and losartan have trial data showing benefit in hypertensive patients with type II diabetes, and may delay the progression of diabetic nephropathy. A 1998 double-blind study found "that lisinopril improved insulin sensitivity whereas losartan did not affect it."[1] Candesartan is used experimentally in preventive treatment of migraine.[2][3] Lisinopril has been found less often effective than candesartan at preventing migraine.[4]

The angiotensin II receptor blockers have differing potencies in relation to blood pressure control, with statistically differing effects at the maximal doses.[5] When used in clinical practice, the particular agent used may vary based on the degree of response required.

Some of these drugs have a uricosuric effect.[6][7]

In one study after 10 weeks of treatment with an ARB called losartan (Cozaar), 88% of hypertensive males with sexual dysfunction reported improvement in at least one area of sexuality, and overall sexual satisfaction improved from 7.3% to 58.5%.[8] In a study comparing beta-blocker carvedilol with valsartan, the angiotensin II receptor blocker not only had no deleterious effect on sexual function, but actually improved it.[9] Other ARBs include candesartan (Atacand), telmisartan (Micardis), and Valsartan (Diovan), fimasartan (Kanarb).

Angiotensin II, through AT1 receptor stimulation, is a major stress hormone and, because (ARBs) block these receptors, in addition to their eliciting anti-hypertensive effects, may be considered for the treatment of stress-related disorders.[10]

In 2008, they were reported to have a remarkable negative association with Alzheimer's disease (AD). A retrospective analysis of five million patient records with the US Department of Veterans Affairs system found different types of commonly used antihypertensive medications had very different AD outcomes. Those patients taking angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) were 35—40% less likely to develop AD than those using other antihypertensives.[11][12]

History

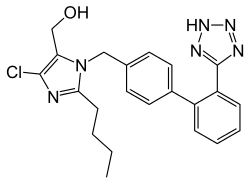

Structure

Losartan, irbesartan, olmesartan, candesartan, valsartan and fimasartan include the tetrazole group (a ring with four nitrogen and one carbon). Losartan, irbesartan, olmesartan, candesartan, and telmisartan include one or two imidazole groups.

Mechanism of action

These substances are AT1-receptor antagonists; that is, they block the activation of angiotensin II AT1 receptors. Blockage of AT1 receptors directly causes vasodilation, reduces secretion of vasopressin, and reduces production and secretion of aldosterone, among other actions. The combined effect reduces blood pressure.

The specific efficacy of each ARB within this class depends upon a combination of three pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters. Efficacy requires three key PD/PK areas at an effective level; the parameters of the three characteristics will need to be compiled into a table similar to one below, eliminating duplications and arriving at consensus values; the latter are at variance now.

Pressor inhibition

Pressor inhibition at trough level - this relates to the degree of blockade or inhibition of the blood pressure-raising ("pressor") effect of angiotensin II. However, pressor inhibition is not a measure of blood pressure-lowering (BP) efficacy per se. The rates as listed in the US FDA Package Inserts (PIs) for inhibition of this effect at the 24th hour for the ARBs are as follows: (all doses listed in PI are included)

- Valsartan 80 mg 30%

- Telmisartan 80 mg 40%

- Losartan 100 mg 25–40%

- Irbesartan 150 mg 40%

- Irbesartan 300 mg 60%

- Azilsartan 32 mg 60%

- Olmesartan 20 mg 61%

- Olmesartan 40 mg 74%

AT1 affinity

AT1 affinity vs AT2 is not a meaningful efficacy measurement of BP response. The specific AT1 affinity relates to how specifically attracted the medicine is for the correct receptor, the US FDA PI rates for AT1 affinity are as follows:

- Losartan 1000-fold

- Telmisartan 3000-fold

- Irbesartan 8500-fold

- Candesartan greater than 10000-fold

- Olmesartan 12500-fold

- Valsartan 30000-fold

- Saprisartan[13]

Biological half-life

The third area needed to complete the overall efficacy picture of an ARB is its biological half-life. The half-lives from the US FDA PIs are as follows:

- Valsartan 6 hours

- Losartan 6–9 hours

- Azilsartan 11 hours

- Irbesartan 11–15 hours

- Olmesartan 13 hours

- Telmisartan 24 hours

- Fimasartan 7–11 hours

Drug comparison and pharmacokinetics

| Drug | Trade Name | Biological half-life [h] | Protein binding [%] | Bioavailability [%] | Renal/hepatic clearance [%] | Food effect | Daily dosage [mg] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Losartan | Cozaar | 6-9 h | 98.7% | 33% | 10%/90% | Minimal | 50–100 mg |

| EXP 3174 | 6–9 h | 99.8% | – | 50%/50% | – | – | |

| Candesartan | Atacand | 9h | >99% | 15% | 60%/40% | No | 4–32 mg |

| Valsartan | Diovan | 6 h | 95% | 25% | 30%/70% | No | 80–320 mg |

| Irbesartan | Avapro | 11–15 h | 90–95% | 70% | 1%/99% | No | 150–300 mg |

| Telmisartan | Micardis | 24 h | >99% | 42–58% | 1%/99% | No | 40–80 mg |

| Eprosartan | Teveten | 5 h | 98% | 13% | 30%/70% | No | 400–800 mg |

| Olmesartan | Benicar/Olmetec | 14–16 h | >99% | 29% | 40%/60% | No | 10–40 mg |

| Azilsartan | Edarbi | 11 h | >99% | 60% | 55%/42% | No | 40–80 mg |

| Fimasartan | Kanarb | 7-11 h | >97% | 30-40% | - | - | 30–120 mg |

Adverse effects

This class of drugs is usually well tolerated. Common adverse drug reactions (ADRs) include: dizziness, headache, and/or hyperkalemia. Infrequent ADRs associated with therapy include: first dose orthostatic hypotension, rash, diarrhea, dyspepsia, abnormal liver function, muscle cramp, myalgia, back pain, insomnia, decreased hemoglobin levels, renal impairment, pharyngitis, and/or nasal congestion.[14]

While one of the main rationales for the use of this class is the avoidance of dry cough and/or angioedema associated with ACE inhibitor therapy, rarely they may still occur. In addition, there is also a small risk of cross-reactivity in patients having experienced angioedema with ACE inhibitor therapy.[14]

Myocardial infarction: the controversy

The issue of whether angiotensin II receptor antagonists slightly increase the risk of myocardial infarction (MI or heart attack) is currently being investigated. Some studies suggest ARBs can increase the risk of MI.[15] However, other studies have found ARBs do not increase the risk of MI.[16] To date, with no consensus on whether ARBs have a tendency to increase the risk of myocardial infarction, further investigations are underway.

Indeed, as a consequence of AT1 blockade, ARBs increase angiotensin II levels several-fold above baseline by uncoupling a negative-feedback loop. Increased levels of circulating angiotensin II result in unopposed stimulation of the AT2 receptors, which are, in addition, upregulated. However, recent data suggest AT2 receptor stimulation may be less beneficial than previously proposed, and may even be harmful under certain circumstances through mediation of growth promotion, fibrosis, and hypertrophy, as well as eliciting proatherogenic and proinflammatory effects.[17][18][19]

Cancer risk factors

A study published in 2010 determined that "...meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials suggests that ARBs are associated with a modestly increased risk of new cancer diagnosis. Given the limited data, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the exact risk of cancer associated with each particular drug. These findings warrant further investigation." [20] A later meta-analysis by the FDA of 31 randomized controlled trials comparing ARBs to other treatment found no evidence of an increased risk of incident (new) cancer, cancer-related death, breast cancer, lung cancer, or prostate cancer in patients receiving ARBs.[21] In 2013, comparative effectiveness research from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs on the experience of more than a million Veterans found no increased risks for either lung cancer [22] (original article in Journal of Hypertension) or prostate cancer [23] (original article in The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology). The researchers concluded "In this large nationwide cohort of United States Veterans, we found no evidence to support any concern of increased risk of lung cancer among new users of ARBs compared with nonusers. Our findings were consistent with a protective effect of ARBs." [22]

In May 2013, a senior regulator at the Food & Drug Administration, Medical Team Leader Thomas A. Marciniak, revealed publicly that contrary to the FDA's official conclusion that there was no increased cancer risk, after a patient by patient examination of the available FDA data he had concluded that there was a lung-cancer risk increase of about 24% in ARB patients, compared with patients taking a placebo or other drugs. One of the criticisms Marciniak made was that the earlier FDA meta-analysis did not count lung carcinomas as cancers. In ten of the eleven studies he examined, Marciniak said that there were more lung cancer cases in the ARB group than the control group. Ellis Unger, chief of the drug-evaluation division that includes Dr. Marciniak, was quoted as calling the complaints a "diversion," and saying in an interview, "We have no reason to tell the public anything new." In an article about the dispute, the Wall Street Journal interviewed three other doctors to get their views; one had "no doubt" ARBs increased cancer risk, one was concerned and wanted to see more data, and the third thought there was either no relationship or a hard to detect, low-frequency relationship.[24]

Longevity promotion

Knockout of the Agtr1a gene that encodes AT1 results in marked prolongation of the life-span of mice by 26% compared to controls. The likely mechanism is reduction of oxidative damage (especially to mitochondria) and overexpression of renal prosurvival genes. The ARBs seem to have the same effect.[25][26]

Fibrosis regression

Losartan and other ARBs regress liver, heart, lung and kidney fibrosis.

Dilated aortic root regression

A 2003 study using candesartan and valsartan demonstrated an ability to regress dilated aortic root size.[27]

References

- ↑ Fogari R, Zoppi A, Corradi L, Lazzari P, Mugellini A, Lusardi P (1998). "Comparative effects of lisinopril and losartan on insulin sensitivity in the treatment of non diabetic hypertensive patients". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 46 (5): 467–71. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00811.x. PMC 1873694

. PMID 9833600.

. PMID 9833600. - ↑ Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, Sand T, Bovim G (2003). "Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 1 (289 Pt 1): 65–9. doi:10.1001/jama.289.1.65. PMID 12503978.

- ↑ Cernes R, Mashavi M, Zimlichman R (2011). "Differential clinical profile of candesartan compared to other angiotensin receptor blockers". Vasc Health Risk Manag. 7: 749–59. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S22591. PMC 3253768

. PMID 22241949.

. PMID 22241949. - ↑ Gales BJ, Bailey EK, Reed AN, Gales MA (February 2010). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for the prevention of migraines". Ann Pharmacother. 44 (2): 360–6. doi:10.1345/aph.1M312. PMID 20086184.

- ↑ Kassler-Taub K, Littlejohn T, Elliott W, Ruddy T, Adler E (1998). "Comparative efficacy of two angiotensin II receptor antagonists, irbesartan and losartan in mild-to-moderate hypertension. Irbesartan/Losartan Study Investigators". Am J Hypertens. 11 (4 Pt 1): 445–53. doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(97)00491-3. PMID 9607383.

- ↑ Dang A, Zhang Y, Liu G, Chen G, Song W, Wang B (January 2006). "Effects of losartan and irbesartan on serum uric acid in hypertensive patients with hyperuricaemia in Chinese population". J Hum Hypertens. 20 (1): 45–50. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001941. PMID 16281062.

- ↑ Daskalopoulou SS, Tzovaras V, Mikhailidis DP, Elisaf M (2005). "Effect on serum uric acid levels of drugs prescribed for indications other than treating hyperuricaemia". Curr. Pharm. Des. 11 (32): 4161–75. doi:10.2174/138161205774913309. PMID 16375738.

- ↑ Llisterri, JL; Lozano Vidal, JV; Aznar Vicente, J; Argaya Roca, M; Pol Bravo, C; Sanchez Zamorano, MA; Ferrario, CM (2001). "Sexual dysfunction in hypertensive patients treated with losartan". The American journal of the medical sciences. 321 (5): 336–41. doi:10.1097/00000441-200105000-00006. PMID 11370797.

- ↑ Fogari, R; Zoppi, A; Poletti, L; Marasi, G; Mugellini, A; Corradi, L (2001). "Sexual activity in hypertensive men treated with valsartan or carvedilol: A crossover study". American Journal of Hypertension. 14 (1): 27–31. doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(00)01214-0. PMID 11206674.

- ↑ Pavel, J; Benicky, J; Murakami, I; Sanchez-Lemus, Y; Saavedra, E; Zhou, J; Saavedra, JM (2008). "Peripherally administered Angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonists are anti-stress compounds in vivo". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1148: 360–366. doi:10.1196/annals.1410.006. PMC 2659765

. PMID 19120129.

. PMID 19120129. - ↑ Li NC, Lee A, Whitmer RA, Kivipelto M, Lawler E, Kazis LE, Wolozin B (2010). "Use of angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of dementia in a predominantly male population: prospective cohort analysis". BMJ. 340 (9): b5465. doi:10.1136/bmj.b5465. PMC 2806632

. PMID 20068258.

. PMID 20068258. - ↑ "Potential of antihypertensive drugs for the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer's disease". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 8 (9): 1286. September 2008. doi:10.1586/14737175.8.9.1285.

- ↑ http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB01347

- 1 2 Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- ↑ Strauss MH, Hall AS (2006). "Angiotensin receptor blockers may increase risk of myocardial infarction: unraveling the ARB-MI paradox". Circulation. 114 (8): 838–54. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594986. PMID 16923768.

- ↑ Tsuyuki RT, McDonald MA (2006). "Angiotensin receptor blockers do not increase risk of myocardial infarction". Circulation. 114 (8): 855–60. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594978. PMID 16923769.

- ↑ Levy BI (2005). "How to explain the differences between renin angiotensin system modulators". Am. J. Hypertens. 18 (9 Pt 2): 134S–141S. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.005. PMID 16125050.

- ↑ Lévy BI (2004). "Can angiotensin II type 2 receptors have deleterious effects in cardiovascular disease? Implications for therapeutic blockade of the renin-angiotensin system". Circulation. 109 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000096609.73772.C5. PMID 14707017.

- ↑ Reudelhuber TL (2005). "The continuing saga of the AT2 receptor: a case of the good, the bad, and the innocuous". Hypertension. 46 (6): 1261–2. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000193498.07087.83. PMID 16286568.

- ↑ Sipahi I; Debanne, SM; Rowland, DY; Simon, DI; Fang, JC (2010). "Angiotensin-receptor blockade and risk of cancer: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Lancet Oncol. 11 (7): 627–36. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70106-6. PMID 20542468.

- ↑ "Angiotensin FDA Drug Safety Communication: No increase in risk of cancer with certain blood pressure drugs--Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2 June 2011.

- 1 2 Rao GA; Mann, JR; Shoaibi, A; Pai, SG; Bottai, M; Sutton, SS; Haddock, KS; Bennett, CL; Hebert, JR (2010). "Angiotensin receptor blockers: are they related to lung cancer?". J Hypertens. 31 (8): 1669–75. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283621ea3. PMC 3879726

. PMID 23822929.

. PMID 23822929. - ↑ Rao GA; Mann, JR; Bottai, M; Uemura, H; Burch, JB; Bennett, CL; Haddock, KS; Hebert, JR (2013). "Angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of prostate cancer among United States veterans". J Clin Pharmacol. 53 (7): 773–8. doi:10.1002/jcph.98. PMC 3768141

. PMID 23686462.

. PMID 23686462. - ↑ http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424127887324682204578515172395384146

- ↑ Benigni A, Corna D, Zoja C, Sonzogni A, Latini R, Salio M, Conti S, Rottoli D, Longaretti L, Cassis P, Morigi M, Coffman T, Remuzzi G (2009). "Disruption of the Ang II type 1 receptor promotes longevity in mice". J. Clin. Invest. 119 (3): 524–30. doi:10.1172/JCI36703. PMC 2648681

. PMID 19197138.

. PMID 19197138. - ↑ Cassis P, Conti S, Remuzzi G, Benigni A (January 2010). "Angiotensin receptors as determinants of life span". Pflugers Arch. 459 (2): 325–32. doi:10.1007/s00424-009-0725-4. PMID 19763608.

- ↑ Weinberg, Marc S.; Adam J. Weinberg; Raymond B Cord; Horace Martin (2003). "P-609: Regression of dilated aortic roots using supramaximal and usual doses of angiotensin receptor blockers". American Journal of Hypertension. 16 (5): A259. doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(03)00782-9. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

In conclusion, we demonstrated regression of DAR using ARBs at moderate and supramaximal doses. Intensive ARB therapy offers a promise to reduce the natural progression of disease in patients with DARs.

External links

- Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor Blockers at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)