Barangay

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Philippines |

|

Legislature

|

|

Constitutional Commissions |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Administrative divisions of the Philippines |

|---|

|

Provinces and ind. cities |

|

Municipalities and comp. cities |

|

Barangays |

| Administrative division codes (ISO) (FIPS) |

A barangay (Brgy. or Bgy.; Filipino: baranggay, [baɾaŋˈɡaj]; also pronounced the same in Spanish), formerly referred to as barrio, is the smallest administrative division in the Philippines and is the native Filipino term for a village, district or ward. In colloquial usage, the term often refers to an inner city neighbourhood, a suburb or a suburban neighborhood.[1] The word barangay originated from balangay, a kind of boat used by a group of Austronesian peoples when they migrated to the Philippines.[2]

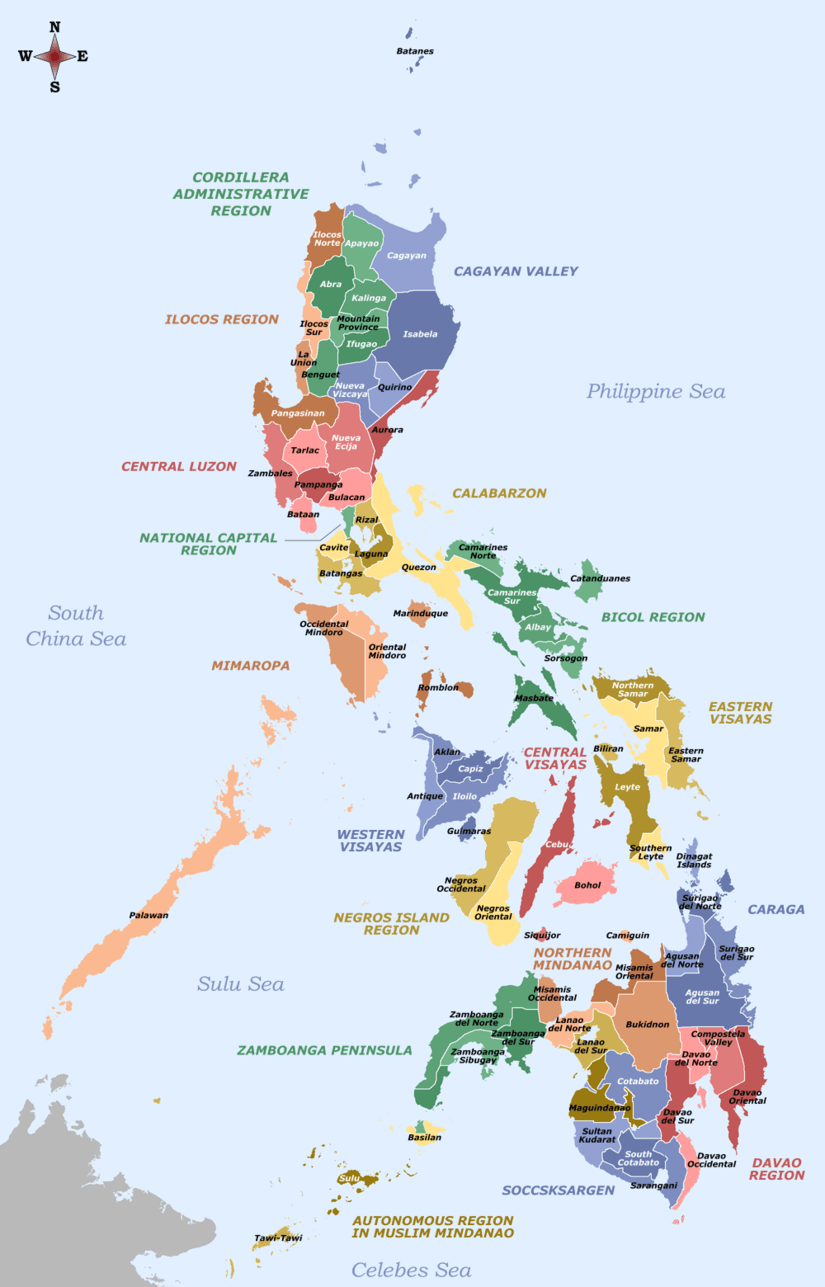

Municipalities and cities in the Philippines are subdivided into barangays, with the exception of the municipalities of Adams in Ilocos Norte and Kalayaan, Palawan which are composed of only one barangay. The barangay itself is sometimes informally subdivided into smaller areas called puroks (English: zone), barangay zones consisting of a cluster of houses, and sitios, which are territorial enclaves—usually rural—far from the barangay center. As of June 2015, there were now 42,029 barangays throughout the Philippines.[3]

History

When the first Spaniards arrived in the Philippines in the 16th century, they found well-organized independent villages called barangays. The name barangay originated from balangay, a Malay word meaning "sailboat".[2]

The first barangays started as relatively small communities of around 50 to 100 families. By the time of contact with Spaniards, many barangays have developed into large communities. The encomienda of 1604 shows that many affluent and powerful coastal barangays in Sulu, Butuan, Panay,[4] Leyte and Cebu, Pampanga, Pangasinan, Pasig, Laguna, and Cagayan River were flourishing trading centers. Some of these barangays had large populations. In Panay, some barangays had 20,000 inhabitants; in Leyte (Baybay), 15,000 inhabitants; in Cebu, 3,500 residents; in Vitis (Pampanga), 7,000 inhabitants; Pangasinan, 4,000 residents. There were smaller barangays with less number of people. But these were generally inland communities; or if they were coastal, they were not located in areas which were good for business pursuits.[5] These smaller barangays had around thirty to one hundred houses only, and the population varies from one hundred to five hundred persons. According to Legazpi, he found communities with twenty to thirty people only.

Traditionally,[6] the original “barangays” were coastal settlements of the migration of these Malayo-Polynesian people (who came to the archipelago) from other places in Southeast Asia (see chiefdom). Most of the ancient barangays were coastal or riverine in nature. This is because most of the people were relying on fishing for supply of protein and for their livelihood. They also travelled mostly by water up and down rivers, and along the coasts. Trails always followed river systems, which were also a major source of water for bathing, washing, and drinking.

The coastal barangays were more accessible to trade with foreigners. These were ideal places for economic activity to develop. Business with traders from other countries also meant contact with other cultures and civilizations, such as those of Japan, Han Chinese, Indian people, and Arab people.[7] These coastal communities acquired more cosmopolitan cultures, with developed social structures (sovereign principalities), ruled by established royalties and nobilities.

During the Spanish rule, through a resettlement policy called the Reducción, smaller scattered barangays were consolidated (and thus, "reduced") to form compact towns.[8][9] Each barangay was headed by the cabeza de barangay (barangay chief), who formed part of the Principalía - the elite ruling class of the municipalities of the Spanish Philippines. This position was inherited from the first datus, and came to be known as such during the Spanish regime. The Spanish Monarch ruled each barangay through the Cabeza, who also collected taxes (called tribute) from the residents for the Spanish Crown.

When the Americans arrived, "slight changes in the structure of local government was effected".[10] Later, Rural Councils with four councilors were created to assist, now renamed Barrio Lieutenant; it was later renamed Barrio Council, and then Barangay Council.[10]

The Spanish term barrio (abbv. "Bo.") was used for much of the 20th century until 1974, when President Ferdinand Marcos ordered their renaming to barangays.[11] The name survived the 1986 EDSA Revolution, though older people would still use the term barrio. The Municipal Council was abolished upon transfer of powers to the barangay system. Marcos used to call the barangay part of Philippine participatory democracy, and most of his writings involving the New Society praised the role of baranganic democracy in nation-building.[12]

After the 1986 EDSA Revolution and the drafting of the 1987 Constitution, the Municipal Council was restored, making the barangay the smallest unit of Philippine government.

Organization

The modern barangay is headed by elected officials, the topmost being the Punong Barangay or the Barangay Chairperson (addressed as Kapitan; also known as the Barangay Captain). The Kapitan is aided by the Sangguniang Barangay (Barangay Council) whose members, called Barangay Kagawad ("Councilors"), are also elected.

The council is considered to be a Local Government Unit (LGU), similar to the Provincial and the Municipal Government. The officials that make up the council are the Punong Barangay, seven Barangay Councilors, and the chairman of Youth Council or Sangguniang Kabataan (SK). Thus, there are eight (8) members of the Legislative Council in a barangay.[13]

The council if in session for a new solution or a resolution of a bill votes, and if the counsels and the SK are at tie decision, the Captain uses his/her vote. This only happens when the SK which is sometimes stopped and continued. In absence of an SK, the council votes for a nominated Barrio Council President, this president is not like the League of the Barangay Councilors which composes of barangay Captains of a municipality.

The Barangay Justice System or Katarungang Pambarangay is composed of members commonly known as Lupon Tagapamayapa (Justice of the peace). Their function is to conciliate and mediate disputes at the Barangay level so as to avoid legal action and relieve the courts of docket congestion.[14]

Barangay elections are non-partisan and are typically hotly contested. Barangay Captain are elected by first-past-the-post plurality (no runoff voting). Councilors are elected by plurality-at-large voting with the entire barangay as a single at-large district. Each voter can vote up to seven candidates for councilor, with the winners being the seven candidates with the most number of votes. Typically, a ticket usually consists of one candidate for Barangay Captain and seven candidates for the Councilors. Elections for the post of Punong Barangay and barangay kagawads are usually held every three years starting from 2007.

The barangay is often governed from its seat of local government, the barangay hall.

A tanod, or barangay police officer, is an unarmed watchman who fulfills policing functions within the barangay. The number of barangay tanods differ from one barangay to another; they help maintain law and order in the neighborhoods throughout the Philippines.

Funding for the barangay comes from their share of the Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA) with a portion of the allotment set aside for the Sangguniang Kabataan. The exact amount of money is determined by a formula combining the barangay's population and land area.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See also

- Association of Barangay Captains

- Balangay

- Barangay Health Volunteers

- List of barangays of Metro Manila

- Purok

- Sitio

Bibliography

- Constantino, Renato. (1975) The Philippines: A Past Revisited (volume 1). ISBN 971-8958-00-2

- Mamuel Merino, O.S.A., ed., Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1565–1615), Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 1975.

Notes

- ↑ "Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries. June 25, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- 1 2 Zaide, Sonia M. (1999), The Philippines: A Unique Nation, All-Nations Publishing, pp. 62, 420, ISBN 971-642-071-4, citing Plasencia, Fray Juan de (1589), Customs of the Tagalogs, Nagcarlan, Laguna

^ Junker, Laura Lee (2000), Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms, Ateneo de Manila University Press, pp. 74, 130, ISBN 978-971-550-347-1 ISBN 971-550-347-0, ISBN 978-971-550-347-1. - 1 2 "Philippine Standard Geographic Codes as of June 2015" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. June 24, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- ↑ During the early part of the Spanish colonization of the Philippines the Spanish Augustinian Friar, Gaspar de San Agustín, O.S.A., describes Iloilo and Panay as one of the most populated islands in the archipelago and the most fertile of all the islands of the Philippines. He also talks about Iloilo, particularly the ancient settlement of Halaur, as site of a progressive trading post and a court of illustrious nobilities. The friar says: Es la isla de Panay muy parecida a la de Sicilia, así por su forma triangular come por su fertilidad y abundancia de bastimentos... Es la isla más poblada, después de Manila y Mindanao, y una de las mayores, por bojear más de cien leguas. En fertilidad y abundancia es en todas la primera... El otro corre al oeste con el nombre de Alaguer [Halaur], desembocando en el mar a dos leguas de distancia de Dumangas...Es el pueblo muy hermoso, ameno y muy lleno de palmares de cocos. Antiguamente era el emporio y corte de la más lucida nobleza de toda aquella isla...Mamuel Merino, O.S.A., ed., Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1565-1615), Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 1975, pp. 374-376.

- ↑ Cf. F. Landa Jocano, Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage (1998), pp. 157-158, 164

- ↑ Cf. Maragtas (book)

- ↑ Hisona, Harold (2010-07-14). "The Cultural Influences of India, China, Arabia, and Japan". Philippinealmanac.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ Constantino, Renato; Constantino, Letizia R. (1975). "Chapter V - The Colonial Landscape". The Philippines: A Past Revisited (Vol. I) (Sixteenth Printing (January 1998) ed.). Manila, Philippines: Renato Constantino. pp. 60–61. ISBN 971-895-800-2. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ Abinales, Patricio N.; Amoroso, Donna J. (2005). "New States and Reorientations 1368-1764". State and Society in the Philippines. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 53, 55. ISBN 0742510247. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- 1 2 Zamora, Mario D. (1966). "Political Change and Tradition: The Case of Village Asia". In Karigoudar Ishwaran (Editor). International Studies in Sociology and Social Anthropology: Politics and Social Change. Leiden, the Netherlands: E.J. Brill. pp. 247–253. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ↑ "Presidential Decree No. 557; Declaring All Barrios in the Philippines as Barangays, and for Other Purposes". The LawPhil Project. Malacañang, Manila, Philippines. 21 September 1974. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ↑ Marcos, Ferdinand. 1973. "Notes on the New Society of the Philippines."

- ↑ "The Barangay". Local Government Code of the Philippines. Chan Robles Law Library.

- ↑ "Barangay Justice System (BJS), Philippines". ACCESS Facility. Retrieved 13 December 2013.