Byrd Theatre

|

Byrd Theatre | |

|

| |

| |

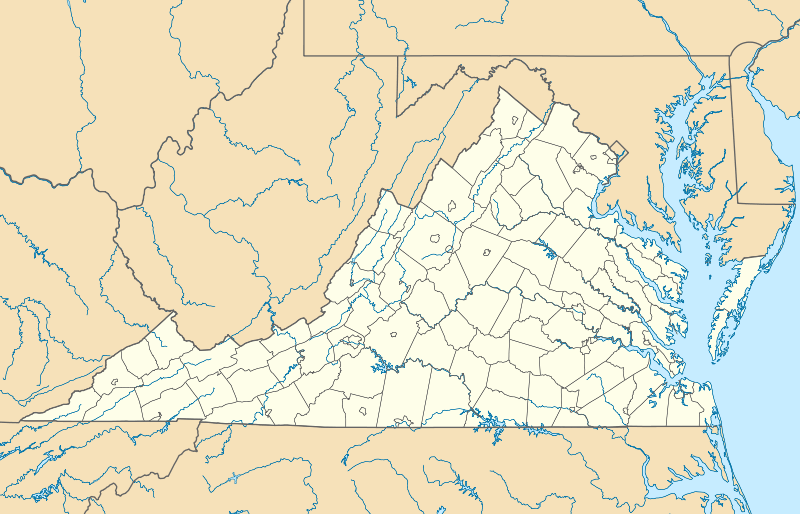

| Location | 2908 W. Cary St., Richmond, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°33′9″N 77°28′41″W / 37.55250°N 77.47806°WCoordinates: 37°33′9″N 77°28′41″W / 37.55250°N 77.47806°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1928 |

| Architect | Fred Bishop |

| Architectural style | Italian Renaissance |

| NRHP Reference # | 79003289[1] |

| VLR # | 127-0287 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 24, 1979 |

| Designated VLR | June 21, 1977[2] |

The Byrd Theatre is a cinema in the Carytown neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia. It was named after William Byrd II, the founder of the city. The theater opened on December 24, 1928 to much excitement and is affectionately referred to as "Richmond’s Movie Palace". It was the first cinema in Virginia to be outfitted when built with a sound system (although other existing theaters had already been retrofitted for sound).[3]

History

Built in 1928, the theater cost $900,000 (inflation adjusted equivalent $12,430,000 in 2014) to construct. The builders were Charles Somma and Walter Coulter. The original name for the theater was the State Theater, but by the completion of the construction the name was already taken. It was then named after William Byrd II, founder of the city of Richmond.[4]

The Byrd Theatre opened for the first time on December 24, 1928. At the time, adult tickets were 50 cents for evening shows and 25 cents for matinees, while a child’s tickets was only 10 cents. The first movie was the film "Waterfront", a First National Film starring Dorothy Mackaill and Jack Mulhall. In addition, the manager at the time was Robert Coulter, who remained the manager until his retirement in 1971 (he is rumored to haunt the theatre).[5][6]

In 1953, the original 35mm Simplex standards were replaced by Simplex 35mm projectors and the theater now uses digital projectors as seen on a Historic Richmond 2015 tour of the projection room.[7][8]

The pre-1953 arc lamp is still used to project the Byrd Theater logo on the curtain.

Architecture

The theatre’s architect and contractor was Fred Bishop, and is considered to be of a Renaissance Revival design. Inside, the theatre contains orchestra seating (main) for 916 and balcony seating for 476. The balcony is open whenever attendance requires and occasionally at other times by making a donation to the Byrd Theatre Foundation. The interior features a lavish design by the Arthur Brunet Studios of New York. In addition to eleven Czechoslovakian Crystal Chandeliers, including an 18-foot, two-and-a-half ton chandelier suspended over the auditorium (with over 5,000 crystals illuminated by 500 red, blue, green and amber lights), the interior features imported Italian and Turkish marble, hand-sewn velvet drapes, and oil on canvas murals of Greek mythology. More unusual features included a central vacuum system and a natural spring which used to supply water to the air conditioning system.

Built during the transition between silent and talking pictures, the designers outfitted the theatre with two sound systems. One of these was Vitaphone, a relatively new sound synchronization system using phonograph records that was commercially developed by Warner Brothers. "The Jazz Singer," generally acknowledged as the first talking film, was recorded using this system. The other original sound system was from Western Electric. Because at the time there was uncertainty whether "talkies" would continue to be popular and a significant number of the films distributed were still silent, the Byrd also included a Wurlitzer Theatre organ.

The Wurlitzer Organ

The Wurlitzer organ of the Byrd Theatre is housed in four rooms on the fourth floor above the stage. The basement also houses a vacuum blower for the piano and an elevator room which raises the organ console to stage level for performances. There is an electrical and pneumatic switching system that aids the organist in choosing which pipes and other devices to use (all of the pipe work, bells, drums, and other effects are acoustic and not electronic). As the sound level of the pipes themselves cannot be changed, the sound levels in the actual auditorium are controlled by large slats called swell shades that open and close to control the volume and a tone chute that carries the sound from the fourth floor.

There is a Lyon and Healy harp which is purely ornamental and does not play, along with a marimba that does play from the organ console in the right box. In the left box there is a Wurlitzer grand piano which can be played from the organ console or its own keyboard and a 37-note xylophone that plays from the console.

House organists have been Carl Rhond, Wilma Beck, Waldo S. Newberry, Slim Mathis, Bill Dalton, Harold Warner, Eddie Weaver, Art Brown, James Hughes, Lin Lunde, and Bob Lent.[3] The Wurlitzer is still played Saturday nights by current house organist Bob Gulledge.

Preservation

As a result of its longevity, the Byrd Theatre was designated as a Virginia Historic Landmark in 1978, followed in 1979 by listing on the National Register of Historic Places.[3] In 2007, the Byrd Theatre Foundation, a non-profit 501(c)(3) corporation, entered into a purchase agreement for the Byrd with the express purpose of restoring and preserving this theatre as a community resource.

Today the theatre still shows movies 365 days a year, and has not been re-modeled (with the exception of repairs and minor changes such as the installment of a larger screen, new digital projection equipment and a concession stand). All the seat frames are still original, and though some are torn, most of the upstairs patterned mohair-covered upholstery is still original.[9] In 2004, Ray Dolby, who created the Dolby Digital sound system, toured the Byrd and was so impressed with the theatre that he donated a Dolby Digital sound system, which was installed in 2006.[8]

The Byrd now plays second-run movies for $2.00 per ticket with the exception of certain festivals such as the Richmond French Film Festival that has been held there annually.[3] In 2007 the Byrd discontinued regular playing of classic movies at midnight shows on Saturday nights due to dwindling attendance.[10] When the Theatre isn’t being used for second-run movies, the Foundation hopes to integrate cultural, educational and community aspects into the Theatre’s programming while still offering movies at reasonable prices.[11]

In 2010, a thief stole the "Byrd Cage" donation box, probably netting less than $100 but causing about $1,200 worth of damage to the front doors. Media coverage following the event, however, inspired Richmonders to donate much needed money for the landmark.[12]

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.byrdtheatre.com/

- ↑ Personally spoke with the Theater manager of over 10 years.

- ↑ Nights And Weekends - Haunted Richmond Review

- ↑ Lohr, Greg (1995-03-27). "Byrd soars with ghosts, nostalgia". Commonwealth Times. Richmond Va. pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Historic Richmond Tour

- 1 2 http://byrdtheatre.com/restoration/history/

- ↑ Personally spoke to the Theater's Head manager of over 10 years

- ↑ Dwindling audiences end late-night flicks at Byrd - Spectrum

- ↑ http://byrdtheatre.com/restoration/overview/

- ↑ http://www2.timesdispatch.com/news/news/2010/aug/05/byrd052-ar-413418/

External links

- Byrd Theatre official website

- archive of earlier official website

- Some photographs inside The Byrd posted on Flickr.

- Richmond, Virginia, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary