Columbus, Nebraska

| Columbus, Nebraska | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Bridge carrying U.S. Highway 30 and U.S. Highway 81 across the Loup River at Columbus | |

| |

| Coordinates: 41°25′58″N 97°21′31″W / 41.43278°N 97.35861°WCoordinates: 41°25′58″N 97°21′31″W / 41.43278°N 97.35861°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Nebraska |

| County | Platte |

| Area[2] | |

| • Total | 10.08 sq mi (26.11 km2) |

| • Land | 9.85 sq mi (25.51 km2) |

| • Water | 0.23 sq mi (0.60 km2) |

| Elevation[1] | 1,447 ft (441 m) |

| Population (2010)[3] | |

| • Total | 22,111 |

| • Estimate (2012[4]) | 22,509 |

| • Density | 2,200/sq mi (850/km2) |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP codes | 68601-68602 |

| Area code | 402 |

| FIPS code | 31-10110 [1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0828280 [1] |

| Website | columbusne.us |

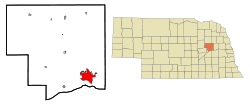

Columbus is a city in and the county seat of Platte County, in the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States.[1] The population was 22,111 at the 2010 census.

History

Pre-settlement

In the 18th century, the area around the confluence of the Platte and the Loup Rivers was used by a variety of Native American tribes, including Pawnee, Otoe, Ponca, and Omaha.[5] The Pawnee are thought to have descended from the Protohistoric Lower Loup Culture;[6] the Otoe had moved from central Iowa into the lower Platte Valley in the early 18th century;[7] and the closely related Omaha and Ponca had moved from the vicinity of the Ohio River mouth, settling along the Missouri by the mid-18th century.[8] In 1720, Pawnee and Otoe allied with the French massacred the Spanish force led by Pedro de Villasur just south of the present site of Columbus.[9][10]

In the 19th century, the "Great Platte River Road"—the valley of the Platte and North Platte rivers running from Fort Kearny to Fort Laramie— was the principal route of the westward expansion.[11] For travellers following the north bank of the Platte, the Loup River, with its soft banks and quicksands, represented a major obstacle. In the absence of a ferry or a bridge, most of these followed the Loup for a considerable distance upstream before attempting a crossing: the first major wave of Mormon emigrants, for instance, continued up that river to a point about three miles downstream from present-day Fullerton.[12]

Settlement and early history

The site of Columbus was settled by the Columbus Town Company on May 28, 1856. The group took its name from Columbus, Ohio, where most of the settlers had originally lived. The townsite was selected for its location on the proposed route of the transcontinental railroad.[13]:5

Just west of the Columbus site, the Elk Horn and Loup Fork Bridge and Ferry Company, headed by James C. Mitchell, had laid out the townsite of Pawnee. In 1855, Mitchell had obtained from the First Nebraska Territorial Legislature the right to operate a ferry across the Loup River. The two companies consolidated in November 1856.[14]:27–28

At the time of its initial settling, the land Columbus occupied still belonged to the Pawnee. However, in 1857, the Pawnee signed a treaty whereunder they gave up the bulk of their Nebraska lands, save for a reservation on what is now Nance County, Nebraska.[15]

In 1858, the Platte County Commissioners passed an act of incorporation making Columbus a town;[16] at this time there were 16 citizens. It became the county seat shortly thereafter.[13]:5 In that same year, at the recommendation of the U.S. Army, a ferry across the Loup was installed;[12] contemporary documents suggest that the Mitchell company had failed to act on its right to operate such a ferry.[14]:30–31

Railroads and growth

Growth of the town was slow until 1863. In that year, construction began in Omaha on the transcontinental railroad. The Homestead Act, passed the previous year, attracted a host of settlers to the Plains and gave rise to increased emigrant traffic business. The ferry across the Loup was replaced by a seasonal pontoon bridge, used in the summer and taken up in the winter.[13]:5 The railroad reached Columbus in June 1866, at which time the city's population was about 75.[16]

The energetic and eccentric promoter George Francis Train envisioned building "a magnificent highway of cities" from coast to coast along the Union Pacific route; Columbus was to be one of these.[17] In 1865, he bought several hundred lots in the city. In the following year, seeing the nearby townsite of Cleveland as a threat to his plans for Columbus, he bought the only building on the site, a hotel, and moved it to Columbus. He renamed the building the Credit Foncier Hotel, after his land company, Credit Foncier of America;[14]:45 in it, he set aside a room permanently reserved for the President of the United States.[13]:6 Train believed that the capital of the United States should be in the geographic center of the nation,[16] and promoted Columbus as "...the new center of the Union and quite probably the future capital of the U.S.A."[18]

Columbus grew and prospered during the 1870s, as a result of both expanding agriculture in Platte County and traffic on the railroad. During the decade, the population of the county grew threefold, and Columbus became the trade center for an eight-county area. The Black Hills Gold Rush in 1875 led the city's merchants to promote it as a staging and outfitting area for gold seekers, who could ride the railroad to Columbus and then travel overland to the gold fields.[19]

In 1879, Columbus became the focus of a war between railroad companies. The Burlington and Missouri proposed to develop a line from Lincoln through Columbus and into northwestern Nebraska, and urged the citizens of Platte County to vote a bond of $100,000 for construction expenses. Union Pacific financier Jay Gould, displeased at the prospect of competition, informed the voters of the county that if the measure passed, he would do his best to ruin Columbus. After a heated campaign, the measure passed despite Gould's threats. The Burlington and Missouri built a line from Lincoln to Columbus, but stopped there; for their diagonal route across Nebraska, they chose one that crossed the Union Pacific at Grand Island rather than Columbus.[14]:324

Gould sought to make good on his threat. When the Union Pacific developed its subsidiary Omaha, Niobrara and Black Hills Railroad, he directed that it cross the Loup River at Lost Creek, then run south to join the Union Pacific's main line at Jackson (since renamed Duncan), bypassing Columbus. Fortunately for Columbus, an ice jam destroyed the Lost Creek bridge in the spring of 1881. Railroad officials agreed to reroute the line down the north bank of the Loup to Columbus in exchange for a $25,000 contribution from the city.[14]:325

Automobile age

In 1911, the Meridian Highway project was launched with the formation of a Meridian Road association in Kansas. Later in that same year, John Nicholson, originator of the highway, spoke at a meeting in Columbus, at which the Nebraska Meridian Road Association was organized. The proposed north-south transcontinental highway crossed the Platte and the Loup rivers at the Columbus bridges. In 1922, it was designated a state highway. The completion of the Meridian Bridge in 1924, replacing a seasonal ferry across the Missouri River at the Nebraska-South Dakota border, made the highway a year-round route from Canada to Mexico. In 1928, the route became U.S. Highway 81.[20]

In 1913, the Lincoln Highway was established as an east-west transcontinental highway. It followed the Platte River route across Nebraska; ultimately, about half of its mileage was on the Union Pacific right-of-way.[21] It also crossed the Loup on the bridge at Columbus.[22] In 1926, the route became U.S. Highway 30.[23]

Traffic on the two transcontinental auto routes through and near central Columbus spurred a burst of commercial construction. Hotels were expanded and new ones built; service garages were opened. To make the route through Columbus more attractive to motorists, the city undertook to illuminate and pave the downtown streets. By 1925, all of the city's major commercial thoroughfares were paved, and almost every lot along 13th Street (the Lincoln Highway) between 23rd and 29th Avenues was occupied by a commercial building.[19]

Rural Platte County suffered badly from the Great Depression. Grain and livestock prices had been high during World War I, engendering a bubble in farmland; to acquire additional acres, farmers had secured them with mortgages not only on the newly purchased land, but on their older holdings. The fall in the prices of agricultural commodities, combined with drought-induced crop failures in 1934 and 1936, forced many such farmers to abandon their lands.[24]:44–5

The civic and commercial leaders of Columbus aggressively sought federal and state funds for local construction projects during this time. In 1931, the Meridian Viaduct was completed, carrying the combined Meridian and Lincoln highways across the Union Pacific tracks and eliminating a grade-level crossing.[14]:328 In 1930–31, the aging and inadequate bridge across the Platte was replaced; in 1932–33, a new bridge was built at the Loup crossing.[22]

Hydro power

The most expensive and ambitious of Columbus's Depression-era public-works efforts was the construction of the Loup Project. This was a 35-mile (56 km) canal running from a diversion weir on the Loup River in Nance County to the Platte River about 1 mile (1.6 km) below the mouth of the Loup.[25]:130–33 The waters of the canal run through two hydroelectric generating stations: one north of Monroe with a capacity of 7,800 kW; and one at Columbus with a capacity of 45,600 kW.[26]

_2.jpg)

Initially financed with a loan and grant of $7.3 million from the Public Works Administration,[25]:124 construction of the diversion structure, canal, and powerhouses began in August 1934[27]:78 and was finished, apart from some final details, in September 1938.[25]:129 At its peak, in October 1936, the project directly employed 1,352 people.[24]:222

To make payments on the Loup Project bonds, the Loup River Public Power District had to find a market for its electricity. Rural electrification was not expanding rapidly; and private power companies in Nebraska were only willing to buy a small fraction of the project's power. Although the provisions of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 gave East Coast holding companies an incentive to sell off their Nebraska subsidiaries, bankers were unwilling to finance their sale to the Loup District because of its debts from the canal project.[25]:139–40

In 1939, Consumers Public Power District was formed in Columbus. The new organization's purpose was to buy power from the Loup Project and from the Tri-County and Sutherland projects on the Platte in central Nebraska; and to market it to consumers and municipal utilities. To this end, it was authorized to issue revenue bonds for the purchase of privately held power companies. By 1942, it had purchased all of the private electrical utilities in Nebraska outside of the immediate vicinity of Omaha;[25]:139–47 by 1949, the last of the private utilities had been bought up, making Nebraska the only state in the nation to be served entirely by public power.[28]

World War II and after

With the arrival of World War II, Columbus's boosters sought a war plant for Columbus. They persuaded the federal government to purchase 90 acres (36 ha) in northeastern Columbus, and to build a railroad line to the site. Before construction of the projected aluminum-extrusion plant could begin, however, it became clear that the war would end soon and that the plant would not be needed.[29] The site was sold as surplus property to the Loup District for a fraction of its original cost; the District turned it into an industrial site.[25]:137–38 In 1946, Behlen Manufacturing built a factory on the site;[14]:389 the rest of the available land was occupied soon thereafter.[25]:138

Geography

Columbus is located at 41°25′58″N 97°21′31″W / 41.43278°N 97.35861°W (41.432785, -97.358530),[1] 85 miles (137 km) west of Omaha and 75 miles (121 km) northwest of Lincoln. It is on the north side of the Loup River near its confluence with the Platte River. U.S. Highways 30 and 81 intersect in the city, and the main line of the Union Pacific railroad passes through it.[29]

The city lies at an elevation of 1,447 feet (441 m). It is built on the flat terrain of the Platte River valley; rolling hills rise to the north of the city.[29]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.08 square miles (26.11 km2), of which, 9.85 square miles (25.51 km2) is land and 0.23 square miles (0.60 km2) is water.[2]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 526 | — | |

| 1880 | 2,131 | 305.1% | |

| 1890 | 3,134 | 47.1% | |

| 1900 | 3,522 | 12.4% | |

| 1910 | 5,014 | 42.4% | |

| 1920 | 5,410 | 7.9% | |

| 1930 | 6,898 | 27.5% | |

| 1940 | 7,632 | 10.6% | |

| 1950 | 8,884 | 16.4% | |

| 1960 | 12,476 | 40.4% | |

| 1970 | 15,471 | 24.0% | |

| 1980 | 17,328 | 12.0% | |

| 1990 | 19,480 | 12.4% | |

| 2000 | 20,971 | 7.7% | |

| 2010 | 22,111 | 5.4% | |

| Est. 2015 | 22,797 | [30] | 3.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] 2012 Estimate[32] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 22,111 people, 8,874 households, and 5,811 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,244.8 inhabitants per square mile (866.7/km2). There were 9,322 housing units at an average density of 946.4 per square mile (365.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.1% White, 0.5% African American, 0.9% Native American, 0.5% Asian, 8.2% from other races, and 1.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 16.3% of the population.

There were 8,874 households of which 32.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.4% were married couples living together, 9.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.5% were non-families. 29.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 3.04.

The median age in the city was 37.1 years. 26.4% of residents were under the age of 18; 8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 24.8% were from 25 to 44; 25.4% were from 45 to 64; and 15.3% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.5% male and 50.5% female.

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 20,971 people, 8,302 households, and 5,562 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,337.3 people per square mile (902.7/km²). There were 8,818 housing units at an average density of 982.8 per square mile (379.6/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 87.19% White, 1.45% African American, 0.35% Native American, 0.48% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 3.49% from other races, and 1.00% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 12.65% of the population.

There were 8,302 households out of which 34.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.7% were married couples living together, 8.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.0% were non-families. 28.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.50 and the average family size was 3.09.

In the city the population was spread out with 28.2% under the age of 18, 8.4% from 18 to 24, 28.0% from 25 to 44, 20.8% from 45 to 64, and 14.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 94.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $38,874, and the median income for a family was $48,669. Males had a median income of $30,980 versus $22,063 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,345. About 4.5% of families and 6.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.7% of those under age 18 and 6.5% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Columbus's economy is based on agriculture and manufacturing, with many industrial companies attracted by cheap, plentiful hydroelectric power. Major manufacturing employers include Becton Dickinson, a medical products company that operates two facilities in Columbus; Behlen Manufacturing, which produces steel buildings, grain bins, and agricultural equipment; CAMACO, a manufacturer of automotive seat frames; Cargill, which operates a ground-beef processing plant; Archer Daniels Midland, which runs a corn-milling facility; and Vishay Dale Electronics, a subsidiary of Vishay Intertechnology that produces electronic components. Major non-manufacturing employers include Nebraska Public Power District, which is headquartered in Columbus; Columbus City Schools; and Columbus Community Hospital.[33]

Media

Columbus has one newspaper, the Columbus Telegram. The newspaper is published six days a week.[34]

There are 6 radio stations in Columbus. KTLX at FM 91.3 is a religious station; KKOT at FM 93.5 plays classic hits. KZEN at FM 100.3 broadcasts country music; the station is licensed in Central City, but the studio is in Columbus. KLIR at FM 101.1 plays adult contemporary music; KJSK at AM 900 is a news talk station; and KTTT at AM 1510, which is a talk radio station.

Columbus has one low-power TV station, KCAZ at LP 57, a Spanish-language station that is available over the air and not on cable.

In August 2014 Mike Flood, former speaker of the Nebraska Legislature, opened the Columbus News Team. Columbus News Team is an online TV style news outlet providing nightly newscasts on ColumbusNewsTeam.com as well as four-camera high school football broadcasts on Friday nights. Columbus News Team is affiliated with KOLN 10/11 News in Lincoln, Nebraska to provide Columbus area content for their newscasts on TV. Columbus News Team also provides audio content to Flood's US92 KUSO and 94 Rock KNEN radio stations in Norfolk, Nebraska.

Education

Central Community College

A campus of Central Community College is located four miles (6 km) northwest of the city. Its athletic teams are the Raiders.[35]

High schools

Columbus has three high schools. The largest is Columbus High School, with 1,100 students. Its athletic teams are the Discoverers.[36] Lakeview High School is the high school for the rural community. It is located just north of Lake Babcock, and its teams are the Vikings. Scotus Central Catholic High School is a Catholic school named after John Duns Scotus; it serves grades 7 through 12. Its teams are the Shamrocks.[37]

Columbus Public Schools

Columbus Public Schools District operates a middle school and five elementary schools: Centennial, West Park, North Park, Lost Creek, and Emerson.[38] The district has closed several elementary schools within the past 10 years, most recently the nearby Duncan Elementary School, which had been in the district since 1967.[39]

Attractions

The Andrew Jackson Higgins National Memorial in Pawnee Park features a life-sized replica of a Higgins boat with bronze statues of soldiers exiting into the sand. The memorial includes sand samples from 58 beaches of historic significance: D-Day beaches of World War II, and beaches in Korea and Vietnam. The site is also home to the Freedom Memorial, which incorporates steel from the remains of the World Trade Center, destroyed by terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.[40]

Glur's Tavern, built in 1876, is the oldest tavern west of the Missouri River still in operation. The tavern was patronized by "Buffalo Bill" Cody during his frequent visits to Columbus.[41] The tavern is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[42]

The Platte County Agricultural Society hosts a number of events at Agricultural Park. The Platte County Fair is held there annually.[43] Live thoroughbred horse racing takes place at the park every year from late July through mid-September; races from other tracks are simulcast throughout the year.[44]

U.S. 30 Speedway stages weekly auto races from April to September.[44]

The Columbus Marching Festival is held every September, hosting High School marching bands from in and outside of the state.[44]

The Columbus Days Parade is held a week in August in downtown Columbus,NE [44]

Notable people

Columbus is the birthplace of Andrew Jackson Higgins, creator/designer of the Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP), or Higgins boat, used during World War II.

Noteworthy current or former residents of Columbus Chuck Hagel, US Secretary of Defense from 2013 to 2015; actor Brad William Henke; world heavyweight boxing champion Leon Spinks; architect Emiel Christensen; and NFL football players Joe Blahak, Cory Schlesinger, and Chad Mustard.

Lucas Cruikshank, creator of YouTube series FRED and its main character Fred Figglehorn, is a former Columbus resident.[45]

Lon Milo DuQuette, occultist author and musician, is a graduate of Columbus High School.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) details for Columbus, Nebraska; United States Geological Survey (USGS); March 9, 1979.

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-01-24. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- ↑ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-06-17. Retrieved 2013-05-29.

- ↑ Olson, James C. and Ronald C. Naugle. History of Nebraska. University of Nebraska Press. 1997. p. 32.

- ↑ "Emergence of Historic Tribes: The Lower Loup Culture". NebraskaStudies.Org. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ↑ "Emergence of Historic Tribes: The Oto & Missouria Tribes". NebraskaStudies.Org. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ↑ "Emergence of Historic Tribes: The Omaha & Ponca Tribes". NebraskaStudies.Org. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ↑ "The Villasur Expedition—1720". Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ↑ "Villasur Sent to Nebraska". NebraskaStudies.Org. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ↑ Mattes, Merrill J. (1969). The Great Platte River Road. Nebraska State Historical Society. p 6.

- 1 2 Mattes (1969), p. 132.

- 1 2 3 4 Evans, Marion Reeder (1936). "80 Years of Progress". Columbus 1856-1936. The Art Printery.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Curry, Margaret. History of Platte County. Culver City, California: Murry & Gee, Inc., 1950.

- ↑ Hyde, George E. (1951). Pawnee Indians. University of Denver Press. p. 183.

- 1 2 3 Platte County, Part 2. Andreas' History of the State of Nebraska. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ↑ Larsen, L.H., B.J. Cottrell, H.A. Dalstrom, and K.C. Dalstrom. (2007) Upstream Metropolis: An Urban Biography of Omaha and Council Bluffs. University of Nebraska Press. p 62.

- ↑ Howard, R.W. (1962) The Great Iron Trail: The Story of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Putnam. p. 206.

- 1 2 Kooiman, Barbara M. and Elizabeth A. Butterfield (1996). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Columbus Commercial Historic District. Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ Slattery, Christina, Chad D. Moffett, and L. Robert Puschendorf (2001). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Meridian Highway. Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ Puschendorf, L. Robert (2007). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Lincoln Highway-Duncan West. Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- 1 2 Fraser, Clayton D. (1991). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Columbus Loup River Bridge. Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ Puschendorf, L. Robert (2000). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Gloe Brothers Service Station. Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- 1 2 Olson, Ralph Eugene (1937). Water Power Development on the Lower Loup River: A Study in Economic Geography. Master's thesis, Department of Geography, University of Nebraska at Lincoln. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Firth, Robert E. (1962). Public Power in Nebraska. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- ↑ "Hydroelectric system". Loup Power District. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ Farritor, Sharon (2006). Power and Progress: The History of Loup Power District 1933-2006. Published by Loup Power District.

- ↑ "The Tri-County Project: Public Power in Nebraska". NebraskaStudies.org. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- 1 2 3 "Community Facts: Columbus, Nebraska". Nebraska Public Power District. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Community Fast Facts Profile: Columbus, Nebraska". Nebraska Public Power District. Retrieved 2011-07-21.

- ↑ Columbus Telegram official website. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ↑ Central Community College-Columbus. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ↑ Columbus High School. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ↑ Scotus Central Catholic Jr.-Sr. High School. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ↑ Columbus Public Schools. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- ↑ "School marks final days with open house" Columbus Telegram. 2008-05-21. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- ↑ Higgins Memorial. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ↑ Frear, Shelley. "Buffalo Bill's Columbus Adventure". True West Magazine. 2006-07-01. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ↑ "Nebraska National Register Sites in Platte County". Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ↑ "Ag Park History." Platte County Agricultural Society. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 "Family Fun." Columbus/Platte County Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- ↑ "Biography for Lucas Cruikshank". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Columbus, Nebraska. |

- City of Columbus

-

"Columbus. A city and the county-seat of Platte County, Neb". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Columbus. A city and the county-seat of Platte County, Neb". New International Encyclopedia. 1905. -

Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). "Columbus, a city of Nebraska". Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P.F. Collier & Son Company.

Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). "Columbus, a city of Nebraska". Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P.F. Collier & Son Company.