Gravity

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

|

Core topics |

Gravity, or gravitation, is a natural phenomenon by which all things with mass are brought toward (or gravitate toward) one another, including planets, stars and galaxies. Since energy and mass are equivalent, all forms of energy, including light, also cause gravitation and are under the influence of it. On Earth, gravity gives weight to physical objects and causes the ocean tides. The gravitational attraction of the original gaseous matter present in the Universe caused it to begin coalescing, forming stars — and the stars to group together into galaxies — so gravity is responsible for many of the large scale structures in the Universe. Gravity has an infinite range, although its effects become increasingly weaker on farther objects.

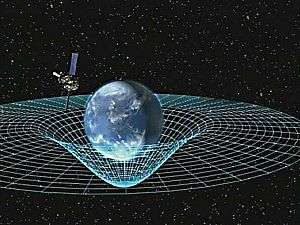

Gravity is most accurately described by the general theory of relativity (proposed by Albert Einstein in 1915) which describes gravity not as a force, but as a consequence of the curvature of spacetime caused by the uneven distribution of mass/energy. The most extreme example of this curvature of spacetime is a black hole, from which nothing can escape once past its event horizon, not even light.[1] More gravity results in gravitational time dilation, where time lapses more slowly at a lower (stronger) gravitational potential. However, for most applications, gravity is well approximated by Newton's law of universal gravitation, which postulates that gravity causes a force where two bodies of mass are directly drawn (or 'attracted') to each other according to a mathematical relationship, where the attractive force is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Gravity is the weakest of the four fundamental interactions of nature. The gravitational attraction is approximately 1038 times weaker than the strong force, 1036 times weaker than the electromagnetic force and 1029 times weaker than the weak force. As a consequence, gravity has a negligible influence on the behavior of subatomic particles, and plays no role in determining the internal properties of everyday matter (but see quantum gravity). On the other hand, gravity is the dominant interaction at the macroscopic scale, and is the cause of the formation, shape and trajectory (orbit) of astronomical bodies. It is responsible for various phenomena observed on Earth and throughout the Universe; for example, it causes the Earth and the other planets to orbit the Sun, the Moon to orbit the Earth, the formation of tides, the formation and evolution of the Solar System, stars and galaxies.

The earliest instance of gravity in the Universe, possibly in the form of quantum gravity, supergravity or a gravitational singularity, along with ordinary space and time, developed during the Planck epoch (up to 10−43 seconds after the birth of the Universe), possibly from a primeval state, such as a false vacuum, quantum vacuum or virtual particle, in a currently unknown manner.[2] For this reason, in part, pursuit of a theory of everything, the merging of the general theory of relativity and quantum mechanics (or quantum field theory) into quantum gravity, has become an area of research.

History of gravitational theory

Earlier Concepts of Gravity

While the modern European thinkers are rightly credited with development of gravitational theory, there were pre-existing ideas which had identified the force of gravity. Some of the earliest descriptions came from early mathematician-astronomers, such as Aryabhata, who had identified the force of gravity to explain why objects do not fall out when the Earth rotates.[3]

Later, the works of Brahmagupta referred to the presence of this force.

Scientific revolution

Modern work on gravitational theory began with the work of Galileo Galilei in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. In his famous (though possibly apocryphal[4]) experiment dropping balls from the Tower of Pisa, and later with careful measurements of balls rolling down inclines, Galileo showed that gravitational acceleration is the same for all objects. This was a major departure from Aristotle's belief that heavier objects have a higher gravitational acceleration.[5] Galileo postulated air resistance as the reason that objects with less mass may fall slower in an atmosphere. Galileo's work set the stage for the formulation of Newton's theory of gravity.[6]

Newton's theory of gravitation

.jpg)

In 1687, English mathematician Sir Isaac Newton published Principia, which hypothesizes the inverse-square law of universal gravitation. In his own words, "I deduced that the forces which keep the planets in their orbs must [be] reciprocally as the squares of their distances from the centers about which they revolve: and thereby compared the force requisite to keep the Moon in her Orb with the force of gravity at the surface of the Earth; and found them answer pretty nearly."[7] The equation is the following:

Where F is the force, m1 and m2 are the masses of the objects interacting, r is the distance between the centers of the masses and G is the gravitational constant.

Newton's theory enjoyed its greatest success when it was used to predict the existence of Neptune based on motions of Uranus that could not be accounted for by the actions of the other planets. Calculations by both John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier predicted the general position of the planet, and Le Verrier's calculations are what led Johann Gottfried Galle to the discovery of Neptune.

A discrepancy in Mercury's orbit pointed out flaws in Newton's theory. By the end of the 19th century, it was known that its orbit showed slight perturbations that could not be accounted for entirely under Newton's theory, but all searches for another perturbing body (such as a planet orbiting the Sun even closer than Mercury) had been fruitless. The issue was resolved in 1915 by Albert Einstein's new theory of general relativity, which accounted for the small discrepancy in Mercury's orbit.

Although Newton's theory has been superseded by the Einstein's general relativity, most modern non-relativistic gravitational calculations are still made using Newton's theory because it is simpler to work with and it gives sufficiently accurate results for most applications involving sufficiently small masses, speeds and energies.

Equivalence principle

The equivalence principle, explored by a succession of researchers including Galileo, Loránd Eötvös, and Einstein, expresses the idea that all objects fall in the same way, and that the effects of gravity are indistinguishable from certain aspects of acceleration and deceleration. The simplest way to test the weak equivalence principle is to drop two objects of different masses or compositions in a vacuum and see whether they hit the ground at the same time. Such experiments demonstrate that all objects fall at the same rate when other forces (such as air resistance and electromagnetic effects) are negligible. More sophisticated tests use a torsion balance of a type invented by Eötvös. Satellite experiments, for example STEP, are planned for more accurate experiments in space.[8]

Formulations of the equivalence principle include:

- The weak equivalence principle: The trajectory of a point mass in a gravitational field depends only on its initial position and velocity, and is independent of its composition.[9]

- The Einsteinian equivalence principle: The outcome of any local non-gravitational experiment in a freely falling laboratory is independent of the velocity of the laboratory and its location in spacetime.[10]

- The strong equivalence principle requiring both of the above.

General relativity

| General relativity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

|

Fundamental concepts |

||||||

|

||||||

In general relativity, the effects of gravitation are ascribed to spacetime curvature instead of a force. The starting point for general relativity is the equivalence principle, which equates free fall with inertial motion and describes free-falling inertial objects as being accelerated relative to non-inertial observers on the ground.[11][12] In Newtonian physics, however, no such acceleration can occur unless at least one of the objects is being operated on by a force.

Einstein proposed that spacetime is curved by matter, and that free-falling objects are moving along locally straight paths in curved spacetime. These straight paths are called geodesics. Like Newton's first law of motion, Einstein's theory states that if a force is applied on an object, it would deviate from a geodesic. For instance, we are no longer following geodesics while standing because the mechanical resistance of the Earth exerts an upward force on us, and we are non-inertial on the ground as a result. This explains why moving along the geodesics in spacetime is considered inertial.

Einstein discovered the field equations of general relativity, which relate the presence of matter and the curvature of spacetime and are named after him. The Einstein field equations are a set of 10 simultaneous, non-linear, differential equations. The solutions of the field equations are the components of the metric tensor of spacetime. A metric tensor describes a geometry of spacetime. The geodesic paths for a spacetime are calculated from the metric tensor.

Solutions

Notable solutions of the Einstein field equations include:

- The Schwarzschild solution, which describes spacetime surrounding a spherically symmetric non-rotating uncharged massive object. For compact enough objects, this solution generated a black hole with a central singularity. For radial distances from the center which are much greater than the Schwarzschild radius, the accelerations predicted by the Schwarzschild solution are practically identical to those predicted by Newton's theory of gravity.

- The Reissner-Nordström solution, in which the central object has an electrical charge. For charges with a geometrized length which are less than the geometrized length of the mass of the object, this solution produces black holes with double event horizons.

- The Kerr solution for rotating massive objects. This solution also produces black holes with multiple event horizons.

- The Kerr-Newman solution for charged, rotating massive objects. This solution also produces black holes with multiple event horizons.

- The cosmological Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker solution, which predicts the expansion of the Universe.

Tests

The tests of general relativity included the following:[13]

- General relativity accounts for the anomalous perihelion precession of Mercury.[14]

- The prediction that time runs slower at lower potentials (gravitational time dilation) has been confirmed by the Pound–Rebka experiment (1959), the Hafele–Keating experiment, and the GPS.

- The prediction of the deflection of light was first confirmed by Arthur Stanley Eddington from his observations during the Solar eclipse of May 29, 1919.[15][16] Eddington measured starlight deflections twice those predicted by Newtonian corpuscular theory, in accordance with the predictions of general relativity. However, his interpretation of the results was later disputed.[17] More recent tests using radio interferometric measurements of quasars passing behind the Sun have more accurately and consistently confirmed the deflection of light to the degree predicted by general relativity.[18] See also gravitational lens.

- The time delay of light passing close to a massive object was first identified by Irwin I. Shapiro in 1964 in interplanetary spacecraft signals.

- Gravitational radiation has been indirectly confirmed through studies of binary pulsars. On 11 February 2016, the LIGO and Virgo collaborations announced the first observation of a gravitational wave.

- Alexander Friedmann in 1922 found that Einstein equations have non-stationary solutions (even in the presence of the cosmological constant). In 1927 Georges Lemaître showed that static solutions of the Einstein equations, which are possible in the presence of the cosmological constant, are unstable, and therefore the static Universe envisioned by Einstein could not exist. Later, in 1931, Einstein himself agreed with the results of Friedmann and Lemaître. Thus general relativity predicted that the Universe had to be non-static—it had to either expand or contract. The expansion of the Universe discovered by Edwin Hubble in 1929 confirmed this prediction.[19]

- The theory's prediction of frame dragging was consistent with the recent Gravity Probe B results.[20]

- General relativity predicts that light should lose its energy when traveling away from massive bodies through gravitational redshift. This was verified on earth and in the solar system around 1960.

Gravity and quantum mechanics

In the decades after the discovery of general relativity, it was realized that general relativity is incompatible with quantum mechanics.[21] It is possible to describe gravity in the framework of quantum field theory like the other fundamental forces, such that the attractive force of gravity arises due to exchange of virtual gravitons, in the same way as the electromagnetic force arises from exchange of virtual photons.[22][23] This reproduces general relativity in the classical limit. However, this approach fails at short distances of the order of the Planck length,[21] where a more complete theory of quantum gravity (or a new approach to quantum mechanics) is required.

Specifics

Earth's gravity

Every planetary body (including the Earth) is surrounded by its own gravitational field, which can be conceptualized with Newtonian physics as exerting an attractive force on all objects. Assuming a spherically symmetrical planet, the strength of this field at any given point above the surface is proportional to the planetary body's mass and inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the center of the body.

The strength of the gravitational field is numerically equal to the acceleration of objects under its influence. The rate of acceleration of falling objects near the Earth's surface varies very slightly depending on latitude, surface features such as mountains and ridges, and perhaps unusually high or low sub-surface densities.[24] For purposes of weights and measures, a standard gravity value is defined by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, under the International System of Units (SI).

That value, denoted g, is g = 9.80665 m/s2 (32.1740 ft/s2).[25][26]

The standard value of 9.80665 m/s2 is the one originally adopted by the International Committee on Weights and Measures in 1901 for 45° latitude, even though it has been shown to be too high by about five parts in ten thousand.[27] This value has persisted in meteorology and in some standard atmospheres as the value for 45° latitude even though it applies more precisely to latitude of 45°32'33".[28]

Assuming the standardized value for g and ignoring air resistance, this means that an object falling freely near the Earth's surface increases its velocity by 9.80665 m/s (32.1740 ft/s or 22 mph) for each second of its descent. Thus, an object starting from rest will attain a velocity of 9.80665 m/s (32.1740 ft/s) after one second, approximately 19.62 m/s (64.4 ft/s) after two seconds, and so on, adding 9.80665 m/s (32.1740 ft/s) to each resulting velocity. Also, again ignoring air resistance, any and all objects, when dropped from the same height, will hit the ground at the same time.

According to Newton's 3rd Law, the Earth itself experiences a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to that which it exerts on a falling object. This means that the Earth also accelerates towards the object until they collide. Because the mass of the Earth is huge, however, the acceleration imparted to the Earth by this opposite force is negligible in comparison to the object's. If the object doesn't bounce after it has collided with the Earth, each of them then exerts a repulsive contact force on the other which effectively balances the attractive force of gravity and prevents further acceleration.

The force of gravity on Earth is the resultant (vector sum) of two forces:[29] (a) The gravitational attraction in accordance with Newton's universal law of gravitation, and (b) the centrifugal force, which results from the choice of an earthbound, rotating frame of reference. The force of gravity is the weakest at the equator because of the centrifugal force caused by the Earth's rotation and because points on the equator are furthest from the center of the Earth. The force of gravity varies with latitude and increases from about 9.780 m/s2 at the Equator to about 9.832 m/s2 at the poles.

Equations for a falling body near the surface of the Earth

Under an assumption of constant gravitational attraction, Newton's law of universal gravitation simplifies to F = mg, where m is the mass of the body and g is a constant vector with an average magnitude of 9.81 m/s2 on Earth. This resulting force is the object's weight. The acceleration due to gravity is equal to this g. An initially stationary object which is allowed to fall freely under gravity drops a distance which is proportional to the square of the elapsed time. The image on the right, spanning half a second, was captured with a stroboscopic flash at 20 flashes per second. During the first 1⁄20 of a second the ball drops one unit of distance (here, a unit is about 12 mm); by 2⁄20 it has dropped at total of 4 units; by 3⁄20, 9 units and so on.

Under the same constant gravity assumptions, the potential energy, Ep, of a body at height h is given by Ep = mgh (or Ep = Wh, with W meaning weight). This expression is valid only over small distances h from the surface of the Earth. Similarly, the expression for the maximum height reached by a vertically projected body with initial velocity v is useful for small heights and small initial velocities only.

Gravity and astronomy

The application of Newton's law of gravity has enabled the acquisition of much of the detailed information we have about the planets in the Solar System, the mass of the Sun, and details of quasars; even the existence of dark matter is inferred using Newton's law of gravity. Although we have not traveled to all the planets nor to the Sun, we know their masses. These masses are obtained by applying the laws of gravity to the measured characteristics of the orbit. In space an object maintains its orbit because of the force of gravity acting upon it. Planets orbit stars, stars orbit galactic centers, galaxies orbit a center of mass in clusters, and clusters orbit in superclusters. The force of gravity exerted on one object by another is directly proportional to the product of those objects' masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

The earliest gravity (possibly in the form of quantum gravity, supergravity or a gravitational singularity), along with ordinary space and time, developed during the Planck epoch (up to 10−43 seconds after the birth of the Universe), possibly from a primeval state (such as a false vacuum, quantum vacuum or virtual particle), in a currently unknown manner.[2]

Gravitational radiation

According to general relativity, gravitational radiation is generated in situations where the curvature of spacetime is oscillating, such as is the case with co-orbiting objects. The gravitational radiation emitted by the Solar System is far too small to measure. However, gravitational radiation has been indirectly observed as an energy loss over time in binary pulsar systems such as PSR B1913+16. It is believed that neutron star mergers and black hole formation may create detectable amounts of gravitational radiation. Gravitational radiation observatories such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) have been created to study the problem. In February 2016, the Advanced LIGO team announced that they had detected gravitational waves from a black hole collision. On September 14, 2015 LIGO registered gravitational waves for the first time, as a result of the collision of two black holes 1.3 billion light-years from Earth.[31][32] This observation confirms the theoretical predictions of Einstein and others that such waves exist. The event confirms that binary black holes exist. It also opens the way for practical observation and understanding of the nature of gravity and events in the Universe including the Big Bang and what happened after it.[33][34]

Speed of gravity

In December 2012, a research team in China announced that it had produced measurements of the phase lag of Earth tides during full and new moons which seem to prove that the speed of gravity is equal to the speed of light.[35] This means that if the Sun suddenly disappeared, the Earth would keep orbiting it normally for 8 minutes, which is the time light takes to travel that distance. The team's findings were released in the Chinese Science Bulletin in February 2013.[36]

Anomalies and discrepancies

There are some observations that are not adequately accounted for, which may point to the need for better theories of gravity or perhaps be explained in other ways.

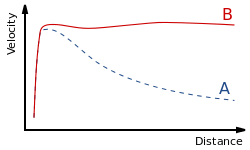

- Extra-fast stars: Stars in galaxies follow a distribution of velocities where stars on the outskirts are moving faster than they should according to the observed distributions of normal matter. Galaxies within galaxy clusters show a similar pattern. Dark matter, which would interact through gravitation but not electromagnetically, would account for the discrepancy. Various modifications to Newtonian dynamics have also been proposed.

- Flyby anomaly: Various spacecraft have experienced greater acceleration than expected during gravity assist maneuvers.

- Accelerating expansion: The metric expansion of space seems to be speeding up. Dark energy has been proposed to explain this. A recent alternative explanation is that the geometry of space is not homogeneous (due to clusters of galaxies) and that when the data are reinterpreted to take this into account, the expansion is not speeding up after all,[37] however this conclusion is disputed.[38]

- Anomalous increase of the astronomical unit: Recent measurements indicate that planetary orbits are widening faster than if this were solely through the Sun losing mass by radiating energy.

- Extra energetic photons: Photons travelling through galaxy clusters should gain energy and then lose it again on the way out. The accelerating expansion of the Universe should stop the photons returning all the energy, but even taking this into account photons from the cosmic microwave background radiation gain twice as much energy as expected. This may indicate that gravity falls off faster than inverse-squared at certain distance scales.[39]

- Extra massive hydrogen clouds: The spectral lines of the Lyman-alpha forest suggest that hydrogen clouds are more clumped together at certain scales than expected and, like dark flow, may indicate that gravity falls off slower than inverse-squared at certain distance scales.[39]

- Power: Proposed extra dimensions could explain why the gravity force is so weak.[40]

Alternative theories

Historical alternative theories

- Aristotelian theory of gravity

- Le Sage's theory of gravitation (1784) also called LeSage gravity, proposed by Georges-Louis Le Sage, based on a fluid-based explanation where a light gas fills the entire Universe.

- Ritz's theory of gravitation, Ann. Chem. Phys. 13, 145, (1908) pp. 267–271, Weber-Gauss electrodynamics applied to gravitation. Classical advancement of perihelia.

- Nordström's theory of gravitation (1912, 1913), an early competitor of general relativity.

- Kaluza Klein theory (1921)

- Whitehead's theory of gravitation (1922), another early competitor of general relativity.

Modern alternative theories

- Brans–Dicke theory of gravity (1961) [41]

- Induced gravity (1967), a proposal by Andrei Sakharov according to which general relativity might arise from quantum field theories of matter

- ƒ(R) gravity (1970)

- Horndeski theory (1974) [42]

- Supergravity (1976)

- String theory

- In the modified Newtonian dynamics (MOND) (1981), Mordehai Milgrom proposes a modification of Newton's Second Law of motion for small accelerations [43]

- The self-creation cosmology theory of gravity (1982) by G.A. Barber in which the Brans-Dicke theory is modified to allow mass creation

- Loop quantum gravity (1988) by Carlo Rovelli, Lee Smolin, and Abhay Ashtekar

- Nonsymmetric gravitational theory (NGT) (1994) by John Moffat

- Conformal gravity[44]

- Tensor–vector–scalar gravity (TeVeS) (2004), a relativistic modification of MOND by Jacob Bekenstein

- Gravity as an entropic force, gravity arising as an emergent phenomenon from the thermodynamic concept of entropy.

- In the superfluid vacuum theory the gravity and curved space-time arise as a collective excitation mode of non-relativistic background superfluid.

- Chameleon theory (2004) by Justin Khoury and Amanda Weltman.

- Pressuron theory (2013) by Olivier Minazzoli and Aurélien Hees.

See also

- Angular momentum

- Anti-gravity, the idea of neutralizing or repelling gravity

- Artificial gravity

- Birkeland current

- Cosmic gravitational wave background

- Einstein–Infeld–Hoffmann equations

- Escape velocity, the minimum velocity needed to escape from a gravity well

- g-force, a measure of acceleration

- Gauge gravitation theory

- Gauss's law for gravity

- Gravitational binding energy

- Gravitational wave

- Gravitational wave background

- Gravity assist

- Gravity gradiometry

- Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment

- Gravity Research Foundation

- Jovian–Plutonian gravitational effect

- Kepler's third law of planetary motion

- Lagrangian point

- Micro-g environment, also called microgravity

- Mixmaster dynamics

- n-body problem

- Newton's laws of motion

- Pioneer anomaly

- Scalar theories of gravitation

- Speed of gravity

- Standard gravitational parameter

- Standard gravity

- Weightlessness

Footnotes

- ↑ "HubbleSite: Black Holes: Gravity's Relentless Pull". hubblesite.org. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- 1 2 Staff. "Birth of the Universe". University of Oregon. Retrieved September 24, 2016. - discusses "Planck time" and "Planck era" at the very beginning of the Universe

- ↑

- Sen, Amartya (2005). The Argumentative Indian. Allen Lane. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7139-9687-6.

- ↑ Ball, Phil (June 2005). "Tall Tales". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news050613-10.

- ↑ Galileo (1638), Two New Sciences, First Day Salviati speaks: "If this were what Aristotle meant you would burden him with another error which would amount to a falsehood; because, since there is no such sheer height available on earth, it is clear that Aristotle could not have made the experiment; yet he wishes to give us the impression of his having performed it when he speaks of such an effect as one which we see."

- ↑ Bongaarts, Peter (2014). Quantum Theory: A Mathematical Approach (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-319-09561-5. Extract of page 11

- ↑

- Chandrasekhar, Subrahmanyan (2003). Newton's Principia for the common reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (pp.1–2). The quotation comes from a memorandum thought to have been written about 1714. As early as 1645 Ismaël Bullialdus had argued that any force exerted by the Sun on distant objects would have to follow an inverse-square law. However, he also dismissed the idea that any such force did exist. See, for example,

- ↑ M.C.W.Sandford (2008). "STEP: Satellite Test of the Equivalence Principle". Rutherford Appleton Laboratory. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ↑ Paul S Wesson (2006). Five-dimensional Physics. World Scientific. p. 82. ISBN 981-256-661-9.

- ↑ Haugen, Mark P.; C. Lämmerzahl (2001). Principles of Equivalence: Their Role in Gravitation Physics and Experiments that Test Them. Springer. arXiv:gr-qc/0103067

. ISBN 978-3-540-41236-6.

. ISBN 978-3-540-41236-6. - ↑ "Gravity and Warped Spacetime". black-holes.org. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ↑ Dmitri Pogosyan. "Lecture 20: Black Holes—The Einstein Equivalence Principle". University of Alberta. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ↑ Pauli, Wolfgang Ernst (1958). "Part IV. General Theory of Relativity". Theory of Relativity. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-64152-2.

- ↑ Max Born (1924), Einstein's Theory of Relativity (The 1962 Dover edition, page 348 lists a table documenting the observed and calculated values for the precession of the perihelion of Mercury, Venus, and Earth.)

- ↑ Dyson, F.W.; Eddington, A.S.; Davidson, C.R. (1920). "A Determination of the Deflection of Light by the Sun's Gravitational Field, from Observations Made at the Total Eclipse of May 29, 1919". Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. A. 220 (571–581): 291–333. Bibcode:1920RSPTA.220..291D. doi:10.1098/rsta.1920.0009.. Quote, p. 332: "Thus the results of the expeditions to Sobral and Principe can leave little doubt that a deflection of light takes place in the neighbourhood of the sun and that it is of the amount demanded by Einstein's generalised theory of relativity, as attributable to the sun's gravitational field."

- ↑ Weinberg, Steven (1972). Gravitation and cosmology. John Wiley & Sons.. Quote, p. 192: "About a dozen stars in all were studied, and yielded values 1.98 ± 0.11" and 1.61 ± 0.31", in substantial agreement with Einstein's prediction θ☉ = 1.75"."

- ↑ Earman, John; Glymour, Clark (1980). "Relativity and Eclipses: The British eclipse expeditions of 1919 and their predecessors". Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences. 11: 49–85. doi:10.2307/27757471.

- ↑ Weinberg, Steven (1972). Gravitation and cosmology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 194.

- ↑ See W.Pauli, 1958, pp.219–220

- ↑ "NASA's Gravity Probe B Confirms Two Einstein Space-Time Theories". Nasa.gov. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- 1 2 Randall, Lisa (2005). Warped Passages: Unraveling the Universe's Hidden Dimensions. Ecco. ISBN 0-06-053108-8.

- ↑ Feynman, R. P.; Morinigo, F. B.; Wagner, W. G.; Hatfield, B. (1995). Feynman lectures on gravitation. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-62734-5.

- ↑ Zee, A. (2003). Quantum Field Theory in a Nutshell. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01019-6.

- ↑ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (15 December 2014). "The Potsdam Gravity Potato". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA.

- ↑ Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (2006). "The International System of Units (SI)" (PDF) (8th ed.): 131. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

Unit names are normally printed in Roman (upright) type ... Symbols for quantities are generally single letters set in an italic font, although they may be qualified by further information in subscripts or superscripts or in brackets.

- ↑ "SI Unit rules and style conventions". National Institute For Standards and Technology (USA). September 2004. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

Variables and quantity symbols are in italic type. Unit symbols are in Roman type.

- ↑ List, R. J. editor, 1968, Acceleration of Gravity, Smithsonian Meteorological Tables, Sixth Ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., p. 68.

- ↑ U.S. Standard Atmosphere, 1976, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1976. (Linked file is very large.)

- ↑ Hofmann-Wellenhof, B.; Moritz, H. (2006). Physical Geodesy (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-211-33544-4. § 2.1: “The total force acting on a body at rest on the earth’s surface is the resultant of gravitational force and the centrifugal force of the earth’s rotation and is called gravity.”

- ↑ "Milky Way Emerges as Sun Sets over Paranal". www.eso.org. European Southern Obseevatory. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ↑ Clark, Stuart (2016-02-11). "Gravitational waves: scientists announce 'we did it!' – live". the Guardian. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ Castelvecchi, Davide; Witze, Witze (February 11, 2016). "Einstein's gravitational waves found at last". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19361. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ "Scientists announce finding Gravitational Waves confirming Einstein's theory". WorldBreakingNews.

- ↑ "WHAT ARE GRAVITATIONAL WAVES AND WHY DO THEY MATTER?". popsci.com. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑ Chinese scientists find evidence for speed of gravity, astrowatch.com, 12/28/12.

- ↑ TANG, Ke Yun; HUA ChangCai; WEN Wu; CHI ShunLiang; YOU QingYu; YU Dan (February 2013). "Observational evidences for the speed of the gravity based on the Earth tide" (PDF). Chinese Science Bulletin. 58 (4-5): 474–477. doi:10.1007/s11434-012-5603-3. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Dark energy may just be a cosmic illusion, New Scientist, issue 2646, 7 March 2008.

- ↑ Swiss-cheese model of the cosmos is full of holes, New Scientist, issue 2678, 18 October 2008.

- 1 2 Chown, Marcus (16 March 2009). "Gravity may venture where matter fears to tread". New Scientist. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ↑ CERN (20 January 2012). "Extra dimensions, gravitons, and tiny black holes".

- ↑ Brans, C.H. (Mar 2014). "Jordan-Brans-Dicke Theory". Scholarpedia. 9: 31358. Bibcode:2014Schpj...931358B. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.31358.

- ↑ Horndeski, G.W. (Sep 1974). "Second-Order Scalar-Tensor Field Equations in a Four-Dimensional Space". International Journal of Theoretical Physics. 88 (10): 363–384. Bibcode:1974IJTP...10..363H. doi:10.1007/BF01807638.

- ↑ Milgrom, M. (Jun 2014). "The MOND paradigm of modified dynamics". Scholarpedia. 9: 31410. Bibcode:2014SchpJ...931410M. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.31410.

- ↑ Einstein gravity from conformal gravity

References

- Halliday, David; Robert Resnick; Kenneth S. Krane (2001). Physics v. 1. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-32057-9.

- Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W. (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers (6th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-40842-7.

- Tipler, Paul (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Mechanics, Oscillations and Waves, Thermodynamics (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0809-4.

Further reading

- Thorne, Kip S.; Misner, Charles W.; Wheeler, John Archibald (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

External links

| Look up gravity in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gravitation. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Gravitation. |

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Gravitation", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Gravitation, theory of", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4