Republican Party presidential primaries, 1940

| | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

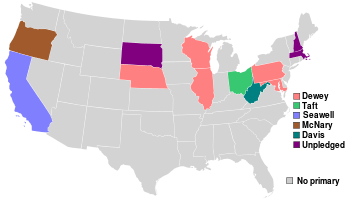

| Results map by state. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1940 Republican presidential primaries were the selection process by which voters of the Republican Party chose its nominee for President of the United States in the 1940 U.S. presidential election. The nominee was selected through a series of primary elections and caucuses culminating in the 1940 Republican National Convention held from June 24 to June 28, 1940, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[1]

In the months leading up to the opening of the 1940 Republican National Convention, the three leading candidates for the GOP nomination were considered to be Senators Robert A. Taft of Ohio and Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan, and District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey of New York. Taft was the leader of the GOP's conservative, isolationist wing, and his main strength was in his native Midwest and parts of the South. Vandenberg, the senior Republican in the Senate, was the "favorite son" candidate of the Michigan delegation and was considered a possible compromise candidate. Dewey, the District Attorney for Manhattan, had risen to national fame as the "Gangbuster" prosecutor who had sent numerous infamous mafia figures to prison, most notably "Lucky" Luciano, the organized-crime boss of New York City. All three men had campaigned vigorously during the primary season, but only 300 of the 1,000 convention delegates had been pledged to a candidate by the time the convention opened. However, each of the three leading candidates had exploitable weaknesses. Taft's outspoken isolationism and opposition to any American involvement in the European war convinced many Republican leaders that he could not win a general election, particularly as France fell to the Nazis in May 1940 and Germany threatened Britain. Dewey's relative youth - he was only 38 in 1940 - and lack of any foreign-policy experience caused his candidacy to weaken as the Nazi military emerged as a fearsome threat. In 1940 Vandenburg was also an isolationist (he changed his foreign-policy stance during World War II ) and his lackadaisical, lethargic campaign never caught the voter's attention. This left an opening for a dark horse candidate to emerge.

A Wall Street-based industrialist named Wendell Willkie, who had never before run for public office, emerged as the unlikely nominee. Willkie, a former Democrat who had been a pro-Roosevelt delegate at the 1932 Democratic National Convention, was considered an improbable choice. Willkie had first come to public attention as an articulate critic of Roosevelt's attempt to break up electrical power monopolies. Willkie was the CEO of the Commonwealth and Southern power company, and he opposed the federal government's attempts to compete with private enterprise, claiming that the government had unfair advantages over private companies. Willkie did not dismiss all Roosevelt's social welfare programs, and in fact he supported those he believed free enterprise could not do better. Furthermore, unlike the leading Republican candidates, Willkie was a forceful and outspoken advocate of aid to the Allies, especially Britain. His support of giving all aid to the British "short of declaring war" won him the support of many Republicans on the East Coast, who disagreed with their party's isolationist leaders in Congress. Willkie's persuasive arguments impressed these Republicans, who believed that he would be an attractive presidential candidate. Many of the leading media magnates of the era, such as Ogden Reid of the New York Herald Tribune, Roy Howard of the Scripps-Howard chain and John and Gardner Cowles, publishers of the Minneapolis Star and the Minneapolis Tribune, as well as the Des Moines Register and Look magazine, supported Willkie in their newspapers and magazines. Even so, Willkie remained a long-shot candidate; the May 8 Gallup Poll showed Dewey at 67% support among Republicans, followed by Vandenberg and Taft, with Willkie at only 3%.

The Nazi Army's rapid blitz into France in May 1940 shook American public opinion, even as Taft was telling a Kansas audience that America must concentrate on domestic issues to prevent Roosevelt from using the international crisis to extend socialism at home. Both Dewey and Vandenburg also continued to oppose any aid to Britain that might lead to war with Germany. Nevertheless, sympathy for the embattled British was mounting daily, and this aided Willkie's candidacy. By mid-June, little over one week before the Republican Convention opened, the Gallup poll reported that Willkie had moved into second place with 17%, and that Dewey was slipping. Fueled by his favorable media attention, Willkie's pro-British statements won over many of the delegates. As the delegates were arriving in Philadelphia, Gallup reported that Willkie had surged to 29%, Dewey had slipped 5 more points to 47%, and Taft, Vandenberg and former President Herbert Hoover trailed at 8%, 8%, and 6% respectively. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps as many as one million, telegrams urging support for Willkie poured in, many from "Willkie Clubs" that had sprung up across the country. Millions more signed petitions circulating everywhere.

Statewide Contest by Winner

| Date | Primary | Thomas Dewey | Jerrold Seawell | Robert A. Taft | Charles McNary | Ryan N. Davis | Arthur Vandenberg | Wendell Willkie | Arthur James | Herbert Hoover | Unpledged |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 12 | New Hampshire | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| April 2 | Wisconsin | 73% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 27% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| April 9 | Illinois | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| April 9 | Nebraska | 59% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 41% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| April 23 | Pennsylvania | 67% | 0% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 1% | 10% | 1% | 0% |

| April 30 | Massachusetts | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| May 5 | South Dakota | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| May 6 | Maryland | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| May 7 | California | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| May 14 | Ohio | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| May 14 | West Virginia | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| May 17 | Oregon | 4% | 0% | 0% | 96% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Candidates

Nominee

Businessman Wendell Willkie of New York

Businessman Wendell Willkie of New York

Withdrew during convention

.jpg)

Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio

Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg of Michigan

Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg of Michigan

The Convention

At the 1940 Republican National Convention itself, keynote speaker Harold Stassen, the Governor of Minnesota, announced his support for Willkie and became his official floor manager. Hundreds of vocal Willkie supporters packed the upper galleries of the convention hall. Willkie's amateur status, his fresh face, appealed to delegates as well as voters. The delegations were selected not by primaries but by party leaders in each state, and they had a keen sense of the fast-changing pulse of public opinion. Gallup found the same thing in polling data not reported until after the convention: Willkie had moved ahead among Republican voters by 44% to only 29% for the collapsing Dewey. As the pro-Willkie galleries repeatedly yelled "We Want Willkie", the delegates on the convention floor began their vote. Dewey led on the first ballot but steadily lost strength thereafter. Both Taft and Willkie gained in strength on each ballot, and by the fourth ballot it was obvious that either Willkie or Taft would be the nominee. The key moments came when the delegations of large states such as Michigan, Pennsylvania, and New York left Dewey and Vandenberg and switched to Willkie, giving him the victory on the sixth ballot. The voting went like this:

| ballot; | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas E. Dewey | 360 | 338 | 315 | 250 | 57 | 11 |

| Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft | 189 | 203 | 212 | 254 | 377 | 310 |

| Wendell L. Willkie | 105 | 171 | 259 | 306 | 429 | 633 |

| Michigan Senator Arthur Vandenberg | 76 | 73 | 72 | 61 | 42 | - |

| Pennsylvania Governor Arthur H. James | 74 | 66 | 59 | 56 | 59 | 1 |

| Massachusetts Rep. Joseph W. Martin | 44 | 26 | - | - | - | - |

| Hanford MacNider | 32 | 34 | 28 | 26 | 4 | 2 |

| Frank E. Gannett | 33 | 30 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| New Hampshire Senator Styles Bridges | 19 | 9 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Former President Herbert Hoover | 17 | - | - | - | 20 | 9 |

| Oregon Senator Charles L. McNary | 3 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 | - |

Willkie's nomination is still considered by most historians to have been one of the most dramatic moments in any political convention. Having given little thought to who he would select as his vice-presidential nominee, Willkie left the decision to convention chairman and Massachusetts Congressman Joe Martin, the House Minority Leader, who suggested Senate Minority Leader Charles L. McNary of Oregon. Despite the fact that McNary had spearheaded a "Stop Willkie" campaign late in the balloting, the candidate picked him to be his running mate:

| Charles L. McNary | 848 |

| Dewey Short | 108 |

| Styles Bridges | 2 |

See also

References

- ↑ "Guide to U.S. Elections - Google Books". Books.google.com. 2016-02-19. Retrieved 2016-02-19.