1972 Republican National Convention

|

1972 presidential election | |

|

Nominees Nixon and Agnew | |

| Convention | |

|---|---|

| Date(s) | August 21–23, 1972 |

| City | Miami Beach, Florida |

| Venue | Miami Beach Convention Center |

| Keynote speaker | Anne Armstrong |

| Candidates | |

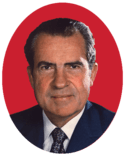

| Presidential nominee | Richard Nixon of California |

| Vice Presidential nominee | Spiro T. Agnew of Maryland |

The 1972 National Convention of the Republican Party of the United States was held from August 21 to August 23, 1972, at the Miami Beach Convention Center in Miami Beach, Florida. It nominated President Richard M. Nixon and Vice President Spiro T. Agnew for reelection. The convention was chaired by then-U.S. House Minority Leader and future Nixon successor Gerald Ford of Michigan. It was the fifth time Nixon had been nominated on the Republican ticket as either its vice-presidential (1952 and 1956) or presidential candidate (1960 and 1968). Hence, Nixon's five appearances on his party's ticket matched the major-party American standard of Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat who had been nominated for Vice President once (in 1920) and President four times (in 1932, 1936, 1940 and 1944).

Site selection

San Diego, California, had originally been selected as host city for the convention. Columnist Jack Anderson, however, discovered a memo written by Dita Beard, a lobbyist for the International Telephone and Telegraph Corp., suggesting the company pledge $400,000 toward the San Diego bid in return for the U.S. Department of Justice settling its antitrust case against ITT.[1] Fearing scandal, and citing labor and cost concerns, the GOP transferred the event—scarcely three months before it was to begin—to Miami Beach, which was also hosting the Democratic National Convention. It was the sixth and, to date, last time both the Republican and Democratic national party conventions were held in the same city; Chicago had hosted double conventions in 1884, 1932, 1944, and 1952, and Philadelphia in 1948.[2] The RNC did not return to San Diego until 1996.

Speeches

The convention set a new standard, as it was scripted as a media event to an unprecedented degree.[3]

The keynote address, by Anne Armstrong of Texas, was the first national convention keynote delivered by a woman.[4]

First Lady Pat Nixon became the first Republican First Lady, and the first First Lady in over 25 years, to address a party's national convention. Her speech set the standard for future convention speeches by political spouses. First Ladies Nancy Reagan, Barbara Bush and Laura Bush, among others, have all followed in this tradition.

Balloting

Nixon easily turned back primary challenges from the right, in the person of U.S. Representative John M. Ashbrook of Ohio and, from the left, Representative Pete McCloskey of California. However, under New Mexico state law, McCloskey had earned one delegate, which the convention refused to seat, fearing that the delegate might put McCloskey's name in nomination and give an anti-war speech. U.S. Representative (and delegate) Manuel Lujan of New Mexico, a staunch Nixon supporter, decided to honor state law by voting for McCloskey himself. The final result was that Nixon received 1,347 votes to one for McCloskey and none for Ashbrook. Throughout the precisely scripted convention, delegates chanted "Four more years! Four more years!"[5]

Spiro Agnew was re-nominated for vice president with 1,345 votes, against one vote for television journalist David Brinkley and two abstentions. The NBC network, for which Brinkley worked, had some "Brinkley for Vice President" buttons made, which the news team wore as a joke.

Protest activity

The convention was targeted for widespread protests, particularly against the Vietnam War, and the Nixon administration made efforts to suppress it. This tension was captured by Top Value Television in the independent documentary Four More Years, which juxtaposes shots of the protests outside the convention with the internal politics of the convention.

In 2005, files released under a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit showed that the Federal Bureau of Investigation even monitored former Beatle John Lennon after he was invited to play for Yippie protests. The monitoring of Lennon later concluded that he was not a dangerous revolutionary, being "constantly under the influence of narcotics." The U.S. Justice Department indicted Scott Camil, John Kniffen, Alton Foss, Donald Perdue, William Patterson, Stan Michelsen, Peter Mahoney and John Briggs—collectively known as the Gainesville Eight—on charges of conspiracy to disrupt the Convention. All were exonerated.

Oliver Stone's film Born on the Fourth of July, based on Ron Kovic's autobiography of the same name, depicts Kovic and fellow Vietnam Veterans Against the War activists Bobby Muller, Bill Wieman and Mark Clevinger being spat upon at the convention.[6] The scene was actually not in Kovic's autobiography, but was taken almost frame for frame and word by word from a documentary film made at the 1972 Republican Convention in Miami 1972 titled "Operation Last Patrol" by filmmaker and actor Frank Cavestani and photo journalist Cathrine Leroy.

See also

References

- ↑ Ancona, Vincent S. (Fall 1992). "When the Elephants Marched Out of San Diego". The Journal of San Diego History. 38 (4). San Diego Historical Society. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ↑ Sautter, R. Craig. "Political Conventions". Encyclopedia of Chicago.

- ↑ "1972 Republican National Convention".

- ↑ Holley, Joe (July 31, 2008). "Leading Texas Republican Anne Armstrong". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ↑ "A New Majority for Four More Years?". TIME. 1972-09-04.

- ↑ JustOneMinute: Who Spat On Whom?

Bibliography

- Ancona, Vincent S. When the Elephants Marched Out of San Diego: The 1972 Republican Convention Fiasco, The Journal of San Diego History, Fall 1992, Volume 38, Number 4

- "Lennon 'too stoned to pose threat'," September 22, 2005, retrieved from CNN.com December 14, 2005.

- Kirkpatrick, Jeane J., "Representation in the American National Conventions: The Case of 1972," British Journal of Political Science, July 1, 1975. Available as a PDF courtesy of the American Enterprise Institute

External links

- Republican Party platform of 1972 at The American Presidency Project

- Nixon acceptance speech at The American Presidency Project

- Nixon, Richard "Remarks on Accepting the Presidential Nomination of the Republican National Convention," August 23, 1972. Provided by the American Presidency Project, University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Four More Years, TVTV Documentary MediaBurn.org: Video Preview

| Preceded by 1968 Miami Beach, Florida |

Republican National Conventions | Succeeded by 1976 Kansas City, Missouri |