Black Stone

The Black Stone (or Hajarul Aswad, Arabic: الحجر الأسود al-Ḥajar al-Aswad) is the eastern cornerstone of the Kaaba, the ancient stone building located in the center of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It is revered by Muslims as an Islamic relic which, according to Muslim tradition, dates back to the time of Adam and Eve.[1]

The stone was venerated at the Kaaba in pre-Islamic pagan times. According to Islamic tradition, it was set intact into the Kaaba's wall by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the year 605 A.D., five years before his first revelation. Since then it has been broken into a number of fragments and is now cemented into a silver frame in the side of the Kaaba. Its physical appearance is that of a fragmented dark rock, polished smooth by the hands of pilgrims. Islamic tradition holds that it fell from the heaven as a guide for Adam and Eve to build an altar, although it has often been described as a meteorite, a hypothesis which is now uncertain.[2]

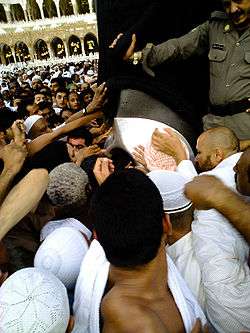

Muslim pilgrims circle the Kaaba as a part of the tawaf ritual during the hajj and many try to stop and kiss the Black Stone, emulating the kiss that Islamic tradition records that it received from Muhammad.[3][4]

Physical description

The Black Stone consists of a number of fragments held together by a silver frame, which is fastened by silver nails to the Kaaba.[5] The smaller fragments have been cemented together to form the seven or eight fragments visible today. The Stone's exposed face measures about 20 centimetres (7.9 in) by 16 centimetres (6.3 in). Its original size is unclear and the recorded dimensions have changed considerably over time, as the stone has been remodelled on several occasions.[2]

In the 10th century, an observer described it as being one cubit (46 cm or 18 in) long. By the early 17th century, it was recorded as measuring 1.40 by 1.22 m (4 ft 7 in by 4 ft 0 in). According to Ali Bey in the 18th century, it was described as 110 cm (3 ft 7 in) high, and Muhammad Ali Pasha reported it as being 76 cm (2 ft 6 in) long by 46 cm (1 ft 6 in) wide.[2]

The Black Stone was first mentioned in Western literature in the 19th and early 20th centuries by European travellers to Arabia, who visited the Kaaba disguised as pilgrims. Swiss traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt visited Mecca in 1814, and provided a detailed description in his 1829 book Travels in Arabia:

It is an irregular oval, about seven inches [18 cm] in diameter, with an undulated surface, composed of about a dozen smaller stones of different sizes and shapes, well joined together with a small quantity of cement, and perfectly well smoothed; it looks as if the whole had been broken into as many pieces by a violent blow, and then united again. It is very difficult to determine accurately the quality of this stone which has been worn to its present surface by the millions of touches and kisses it has received. It appeared to me like a lava, containing several small extraneous particles of a whitish and of a yellow substance. Its colour is now a deep reddish brown approaching to black. It is surrounded on all sides by a border composed of a substance which I took to be a close cement of pitch and gravel of a similar, but not quite the same, brownish colour. This border serves to support its detached pieces; it is two or three inches in breadth, and rises a little above the surface of the stone. Both the border and the stone itself are encircled by a silver band, broader below than above, and on the two sides, with a considerable swelling below, as if a part of the stone were hidden under it. The lower part of the border is studded with silver nails.[6]

Visiting the Kaaba in 1853, Richard Francis Burton also noted that:

The colour appeared to me black and metallic, and the centre of the stone was sunk about two inches below the metallic circle. Round the sides was a reddish-brown cement, almost level with the metal, and sloping down to the middle of the stone. The band is now a massive arch of gold or silver gilt. I found the aperture in which the stone is, one span and three fingers broad.[6]

Ritter von Laurin, the Austrian consul-general in Egypt, was able to inspect a fragment of the Stone removed by Muhammad Ali in 1817 and reported that it had a pitch-black exterior and a silver-grey, fine-grained interior in which tiny cubes of a bottle-green material were embedded. There are reportedly a few white or yellow spots on the face of the Stone, and it is officially described as being white with the exception of the face.[2]

The frame around the Black Stone and the black kiswah or cloth enveloping the Kaaba were for centuries maintained by the Ottoman Sultans in their role as Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques. The frames wore out over time due to the constant handling by pilgrims and were periodically replaced. Worn-out frames were brought back to Istanbul, where they are still kept as part of the sacred relics in the Topkapı Palace.[7]

History and tradition

The Black Stone was held in reverence well before the preaching of Islam by Muhammad. By the time of Muhammad, it was already associated with the Kaaba, a pre-Islamic shrine, that was a sacred sanctuary and a site of pilgrimage of Nabateans who visited the shrine once a year to perform their pilgrimage. The Kaaba held 360 idols of the Meccan gods.[9] The Semitic cultures of the Middle East had a tradition of using unusual stones to mark places of worship, a phenomenon which is reflected in the Hebrew Bible as well as the Qur'an,[10] although bowing to or kissing such sacred objects is repeatedly described in the Tanakh as idolatrous[11] and was the subject of prophetic rebuke.[12][13][14][15][16][17] Some writers remark on the apparent similarity of the Black Stone and its frame to the external female genitalia,[18][19] and ascribe this to its earlier association with fertility rites of Arabia.[20][21]

A "red stone" was associated with the deity of the south Arabian city of Ghaiman, and there was a "white stone" in the Kaaba of al-Abalat (near the city of Tabala, south of Mecca). Worship at that time period was often associated with stone reverence, mountains, special rock formations, or distinctive trees.[22] The Kaaba marked the location where the sacred world intersected with the profane, and the embedded Black Stone was a further symbol of this as an object as a link between heaven and earth.[23]

Muhammad

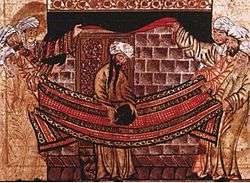

According to Islamic belief Muhammad is credited with setting the Black Stone in the current place in the wall of the Kaaba. A story found in Ibn Ishaq's Sirah Rasul Allah tells how the clans of Mecca renovated the Kaaba following a major fire which had partly destroyed the structure. The Black Stone had been temporarily removed to facilitate the rebuilding work. The clans could not agree on which one of them should have the honour of setting the Black Stone back in its place.[24][25]

They decided to wait for the next man to come through the gate and ask him to make the decision. That person was 35-year-old Muhammad, five years before his prophethood. He asked the elders of the clans to bring him a cloth and put the Black Stone in its centre. Each of the clan leaders held the corners of the cloth and carried the Black Stone to the right spot. Then, Muhammad set the stone in place, satisfying the honour of all of the clans.[24][25]

The Stone has suffered desecrations and significant damage over the course of time. It is said to have been struck and smashed to pieces by a stone fired from a catapult during the Umayyad siege of Mecca in 683. The fragments were rejoined by Abd Allah ibn Zubayr using a silver ligament.[24] In January 930, it was stolen by the Qarmatians, who carried the Black Stone away to their base in Hajar (modern Bahrain). According to Ottoman historian Qutb al-Din, writing in 1857, Qarmatian leader Abu Tahir al-Qarmati set the Black Stone up in his own mosque, the Masjid al-Dirar, with the intention of redirecting the hajj away from Mecca. However, this failed, and pilgrims continued to venerate the spot where the Black Stone had been.[26]

According to historian Al-Juwayni, the Stone was returned twenty-three years later, in 952. The Qarmatians held the Black Stone for ransom, and forced the Abbasids to pay a huge sum for its return. It was wrapped in a sack and thrown into the Friday Mosque of Kufa, accompanied by a note saying "By command we took it, and by command we have brought it back." Its abduction and removal caused further damage, breaking the stone into seven pieces.[10][27][28] Its abductor, Abu Tahir, is said to have met a terrible fate; according to Qutb al-Din, "the filthy Abu Tahir was afflicted with a gangrenous sore, his flesh was eaten away by worms, and he died a most terrible death."[26]

In the 11th century, a man allegedly sent by the Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah attempted to smash the Black Stone, but was killed on the spot, having caused only slight damage.[26] In 1674, according to Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, someone smeared the Black Stone with excrement so that "every one who kissed it retired with a sullied beard". The Shi'ite Persians were suspected of being responsible and were the target of curses from other Muslims for centuries afterwards, though explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton doubted that they were the culprits; he attributed the act to "some Jew or Greek, who risked his life to gratify a furious bigotry."[29]

Ritual role

The Black Stone plays an important role in the central ritual of the hajj, when pilgrims must walk seven times around the Kaaba in a counterclockwise direction. They attempt to kiss the Black Stone seven times, once for each circumambulation of the Kaaba, emulating the actions of Muhammad. In modern times, large crowds make it practically impossible for everyone to kiss the stone, so it is currently acceptable to point in the direction of the Stone on each of their seven circuits around the structure.[30]

Some even say that the Stone is best considered simply as a marker, useful in keeping count of the ritual circumambulations (tawaf) that one has performed.[30] Its black colour is deemed to symbolize the essential spiritual virtue of detachment and poverty for God (faqr) and the extinction of ego required to progress towards God (qalb).[10]

Writing in Dawn in Madinah: A Pilgrim's Progress, Muzaffar Iqbal described his experience of venerating the Black Stone during a pilgrimage to Mecca:

At the end of the second [circumabulation of the Kaaba], I was granted one of those extraordinary moments which sometimes occur around the Black Stone. As I approached the Corner the large crowd was suddenly pushed back by a strong man who had just kissed the Black Stone. This push generated a backward current, creating a momentary opening around the Black Stone as I came to it; I swiftly accepted the opportunity reciting, Bismillahi Allahu akbar wa lillahi-hamd ["In the name of God, God is great, all praise to God"], put my hands on the Black Stone and kissed it. Thousands of silver lines sparkled, the Stone glistened, and something stirred deep inside me. A few seconds passed. Then I was pushed away by the guard.[31]

Meaning and symbolism

Islamic tradition holds that the Black Stone fell from Jannah to show Adam and Eve where to build an altar, which became the first temple on Earth.[32] Muslims believe that the stone was originally pure and dazzling white, but has since turned black because of the sins of the people who touch it.[33][34] According to a prophetic tradition, "Touching them both (the Black Stone and al-Rukn al-Yamani) is an expiation for sins."[35] Adam's altar and the stone were said to have been lost during Noah's Flood and forgotten. Ibrahim was said to have later found the Black Stone at the original site of Adam's altar when the angel Jibrail revealed it to him.[10] Ibrahim ordered his son Ismael — who in Muslim belief is an ancestor of Muhammad — to build a new temple, the Kaaba, into which the Stone was to be embedded.

A hadith records that, when the second Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab (580–644) came to kiss the Stone, he said in front of all assembled: "No doubt, I know that you are a stone and can neither harm anyone nor benefit anyone. Had I not seen Allah's Messenger [Muhammad] kissing you, I would not have kissed you."[36] However, in the hadith collection Kanz al-Ummal, it is recorded that Ali responded to Umar, saying, "This stone (Hajar Aswad) can indeed benefit and harm.... Allah (swt) says in Quran that he created human beings from the progeny of Adam (as) and made them witness over themselves and asked them, 'Am I not your creator?' Upon this, all of them confirmed it. Thus Allah wrote this confirmation. And this stone has a pair of eyes, ears and a tongue and it opened its mouth upon the order of Allah (swt), who put that confirmation in it and ordered to witness it to all those worshippers who come for Hajj."[37]

Muhammad Labib al-Batanuni, writing in 1911, commented on the practice that the pre-Islamic practice of venerating stones (including the Black Stone) arose not because such stones are "sacred for their own sake, but because of their relation to something holy and respected." [38] The Indian Islamic scholar Muhammad Hamidullah summed up the meaning of the Black Stone:

[T]he Prophet has named the (Black Stone) the 'right hand of God' (yamin-Allah), and for purpose. In fact one poses there one's hand to conclude the pact, and God obtains there our pact of allegiance and submission. In the qur'anic terminology, God is the king, and … in (his) realm there is a metropolis (Umm al-Qurra) and in the metropolis naturally a palace (Bait-Allah, home of God). If a subject wants to testify to his loyalty, he has to go to the royal palace and conclude personally the pact of allegiance. The right hand of the invisible God must be visible symbolically. And that is the al-Hajar al-Aswad, the Black Stone in the Ka'bah.[39]

In recent years, however, several literalist views of the Black Stone have emerged. A small minority accepts as literally true an allegorical hadith which asserts that "the Stone will appear on the Day of Judgement (Qiyamah) with eyes to see and a tongue to speak, and give evidence in favor of all who kissed it in true devotion, but speak out against whoever indulged in gossip or profane conversations during his circumambulation of the Kaaba".[38]

Carl Jung notes in Memories, Dreams, Reflections that biblical symbol of stones are numerous, as in this sense the stone symbolizes what is perhaps the deepest experience – the experience of something that is eternal that man can have in those moments when he feels immortal and unalterable. He adds holiest sanctuary of the Islamic world is the Ka'aba, the black stone of Mecca to which all pious Moslems hope to make their pilgrimage at least once in their life.

Scientific origins

The nature of the Black Stone has been much debated. It has been described variously as basalt stone, an agate, a piece of natural glass or—most popularly—a stony meteorite. Paul Partsch, the curator of the Austro-Hungarian imperial collection of minerals, published the first comprehensive history of the Black Stone in 1857 in which he favoured a meteoritic origin for the Stone.[40] Robert Dietz and John McHone proposed in 1974 that the Black Stone was actually an agate, judging from its physical attributes and a report by an Arab geologist that the Stone contained clearly discernible diffusion banding characteristic of agates.[2]

A significant clue to its nature is provided by an account of the Stone's recovery in 951 AD after it had been stolen 21 years earlier; according to a chronicler, the Stone was identified by its ability to float in water. If this account is accurate, it would rule out the Black Stone being an agate, a basalt lava or a stony meteorite, though it would be compatible with it being glass or pumice.[5]

Elsebeth Thomsen of the University of Copenhagen proposed a different hypothesis in 1980. She suggested that the Black Stone may be a glass fragment or impactite from the impact of a fragmented meteorite that fell some 6,000 years ago at Wabar,[41] a site in the Rub' al Khali desert 1,100 km east of Mecca. The craters at Wabar are notable for the presence of blocks of silica glass, fused by the heat of the impact and impregnated with beads of a nickel-iron alloy from the meteorite (most of which was destroyed in the impact). Some of the glass blocks are made of shiny black glass, with a white or yellow interior and gas-filled hollows, which allow them to float on water.[5] Although scientists did not become aware of the Wabar craters until 1932, they were located near a caravan route from Oman and were very likely known to the inhabitants of the desert. The wider area was certainly well-known; in ancient Arabic poetry, Wabar or Ubar (also known as "Iram of the Pillars") was the site of a fabulous city that was destroyed by fire from the heavens because of the wickedness of its king. If the estimated age of the crater is accurate, it would have been well within the period of human habitation in Arabia and the impact itself may have been witnessed.[5] A recent (2004) scientific analysis of the Wabar site suggests that the impact event happened much more recently than first thought and might have occurred only within the last 200–300 years.[42]

The meteoritic hypothesis is now viewed by geologists as doubtful. The British Natural History Museum suggests that it may be a pseudometeorite, in other words a terrestrial rock mistakenly attributed to a meteoritic origin.[43]

Notes

- ↑ Sheikh Safi-ur-Rehman al-Mubarkpuri (2002). Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum (The Sealed Nectar): Biography of the Prophet. Dar-us-Salam Publications. ISBN 1-59144-071-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burke, John G. (1991). Cosmic Debris: Meteorites in History. University of California Press. pp. 221–223. ISBN 978-0-520-07396-8.

- ↑ Elliott, Jeri (1992). Your Door to Arabia. Lower Hutt, N.Z.: R. Eberhardt. ISBN 0-473-01546-3.

- ↑ Mohamed, Mamdouh N. (1996). Hajj to Umrah: From A to Z. Amana Publications. ISBN 0-915957-54-X.

- 1 2 3 4 Alex Bevan, John De Laeter, Meteorites: A Journey Through Space and Time, pp. 14–15. UNSW Press, 2002. ISBN 0-86840-490-X

- 1 2 Quoted in Thomas Patrick Hughes, A Dictionary of Islam, p. 154. W. H. Allen & Co, 1885

- ↑ Aydın, Hilmi (2004). The sacred trusts: Pavilion of the Sacred Relics, Topkapı Palace Museum. Tughra Books. ISBN 978-1-932099-72-0.

- ↑ University of Southern California. "The Prophet of Islam—His Biography". Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Armstrong, Karen (2002-08-02). Islam: A Short History. p. 11. ISBN 0-8129-6618-X.

- 1 2 3 4 Cyril Glasse, New Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 245. Rowman Altamira, 2001. ISBN 0-7591-0190-6

- ↑ Rabinowitz, Louis (2008). "The Biblical Injunction Against Idolatry". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Retrieved 2014-04-20.

- ↑ "The Book of Leviticus, Chapter 26, verse 1". kingjamesbible.com.

- ↑ "The Book of Isaiah, Chapter 2, verse 9". kingjamesbible.com.

- ↑ "The Book of Isaiah, Chapter 44 verse 17-18". kingjamesbible.com.

- ↑ "The Book of Jeremiah, Chapter 2, verse 27". kingjamesbible.com.

- ↑ "the Book of Hosea, chapter 13, verse 2". kingjamesbible.com.

- ↑ "The Book of Habakkuk chapter 2, verse 19". kingjamesbible.com.

- ↑ Tate, Karen (January 1, 2006). Sacred Places of Goddess: 108 Destinations. San Francisco: Consortium of Collective Consciousness Publishing. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-888729-11-5.

- ↑ Camphausen, Rufus (1996). The Yoni, Sacred Symbol of Female Creative Power. Vermont: Inner Traditions Bear and Company. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-89281-562-3.

- ↑ Rice, Edward (May 1978). Eastern Definitions: A Short Encyclopedia of Religions of the Orient. New York: Doubleday. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-385-08563-2.

- ↑ Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad (1955). Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah – The Life of Muhammad Translated by A. Guillaume. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 88–9. ISBN 978-0-19-636033-1.

- ↑ Grunebaum, G. E. von (1970). Classical Islam: A History 600 A.D.–1258 A.D. Aldine Publishing Company. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-202-15016-1.

- ↑ Armstrong, Karen (1996). Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths. A.A. Knopf. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-679-43596-9.

- 1 2 3 Dairesi, Hırka-i Saadet; Aydın, Hilmi (2004). Uğurluel, Talha; Doğru, Ahmet, eds. The sacred trusts: Pavilion of the Sacred Relics, Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul. Tughra Books. ISBN 978-1-932099-72-0.

- 1 2 Muhammad Mustafa Al-A'zami (2003), The History of The Qur'anic Text: From Revelation to Compilation: A Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments, p.24. UK Islamic Academy. ISBN 978-1-872531-65-6.

- 1 2 3 Peters, Francis E. (1994). Mecca: a literary history of the Muslim Holy Land. Princeton University Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-0-691-03267-2.

- ↑ "Qarmatiyyah". Overview of World Religions. St. Martin's College. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ↑ "Black Stone of Mecca (Islam)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Burton, Richard Francis (1856). Personal narrative of a pilgrimage to El-Madinah and Meccah. G. P. Putnam & Co. p. 394.

- 1 2 The Saudi Arabia Information Resource. "The Holy City of Makkah". Retrieved August 12, 2006.

- ↑ Iqbal, Muzaffar (2007). Dawn in Madinah: A Pilgrim's Progress. The Other Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-983-9154-92-4.

- ↑ Muhammad, Martin Lings, Chapter 1. The House of God

- ↑ Saying of the Prophet, Collection of Tirmizi, VII, 49

- ↑ Shaykh Tabarsi, Tafsir, vol. 1, pp. 460, 468. Quoted in translation by Francis E. Peters, Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, p. 5. SUNY Press, 1994. ISBN 0-7914-1876-6

- ↑ ibn Isa at-Tirmidhi, Muhammad. Jami` at-Tirmidhi: Book of Hajj. 2nd, Hadith 959.

- ↑ University of Southern California. "Pilgrimage (Hajj)". Retrieved August 12, 2006.

- ↑ ibn Abd-al-Malik al-Hindi, Ali (1998). Kanz al-Ummal. Lebanon.

- 1 2 Lazarus-Yafeh, Hava (1981). Some religious aspects of Islam: a collection of articles. Leiden: Brill. pp. 120–124. ISBN 978-90-04-06329-7.

- ↑ Shenk, David W. (2006). Journeys of the Muslim nation and the Christian church: exploring the mission of two communities. Uzima Publishing House. p. 161. ISBN 978-9966-855-21-3.

- ↑ Partsch, Paul Maria, "Über den schwarzen Stein der Kaaba zu Mekka, mitgetheilt aus den hinterlassenen Schriften des wirklichen Mitgliedens", Denkschriften der mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Wien, 13 (1857), Erste Abtheilung, 1-5 .

- ↑ New Light on the Origin of the Holy Black Stone of the Ka'ba. Author: Thomsen, E. Journal: Meteoritics, volume 15, number 1, page 87

- ↑ Prescott, J.R., Robertson, G.B., Shoemaker, C., Shoemaker, E.M. and Wynn, J. (2004) "Luminescence dating of the Wabar meteorite craters, Saudi Arabia", Journal of Geophysical Research, 109 (E01008), doi:10.1029/2003JE002136

- ↑ Grady, Monica M.; Graham, A.L. (2000). Grady, Monica M., ed. Catalogue of meteorites: with special reference to those represented in the collection of the Natural History Museum, London. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-521-66303-8.

See also

References

- Grunebaum, G. E. von (1970). Classical Islam: A History 600 A.D.–1258 A.D.. Aldine Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-202-15016-1

- Sheikh Safi-ur-Rahman al-Mubarkpuri (2002). Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum (The Sealed Nectar): Biography of the Prophet. Dar-us-Salam Publications. ISBN 1-59144-071-8.

- Elliott, Jeri (1992). Your Door to Arabia. ISBN 0-473-01546-3.

- Mohamed, Mamdouh N. (1996). Hajj to Umrah: From A to Z. Amana Publications. ISBN 0-915957-54-X.

- Time-Life Books (1988). Time Frame AD 600–800: The March of Islam, ISBN 0-8094-6420-9.

Coordinates: 21°25′21.02″N 39°49′34.58″E / 21.4225056°N 39.8262722°E