Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

| Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument | |

|---|---|

| Staircase National Monument | |

|

IUCN category III (natural monument or feature) | |

| |

| |

| Location | Kane County and Garfield County, Utah, United States |

| Nearest city | Kanab, UT |

| Coordinates | 37°24′0″N 111°41′0″W / 37.40000°N 111.68333°WCoordinates: 37°24′0″N 111°41′0″W / 37.40000°N 111.68333°W |

| Area | 1,880,461 acres (760,996 ha)[1] |

| Established | September 18, 1996 |

| Visitors | 878,000[2] (in 2014) |

| Governing body | U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) |

| Website | Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument |

The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is a U.S. National Monument protecting 1,880,461 acres (760,996 ha)[1] of land in southern Utah.

There are three main regions: the Grand Staircase, the Kaiparowits Plateau, and the Canyons of the Escalante - all of which are administered by the Bureau of Land Management as part of the National Landscape Conservation System. President Bill Clinton designated the area as a national monument in 1996 using his authority under the Antiquities Act. Grand Staircase-Escalante encompasses the largest land area of all U.S. National Monuments.

Management

The Monument is managed by the Bureau of Land Management rather than the National Park Service. This was the first National Monument managed by the BLM. Visitor centers are located in Cannonville, Big Water, Escalante, and Kanab.

Geography

The Monument stretches from the towns of Big Water, Glendale and Kanab, Utah on the southwest, to the towns of Escalante and Boulder on the northeast. Encompassing 1.9 million acres, the monument is slightly larger in area than the state of Delaware.

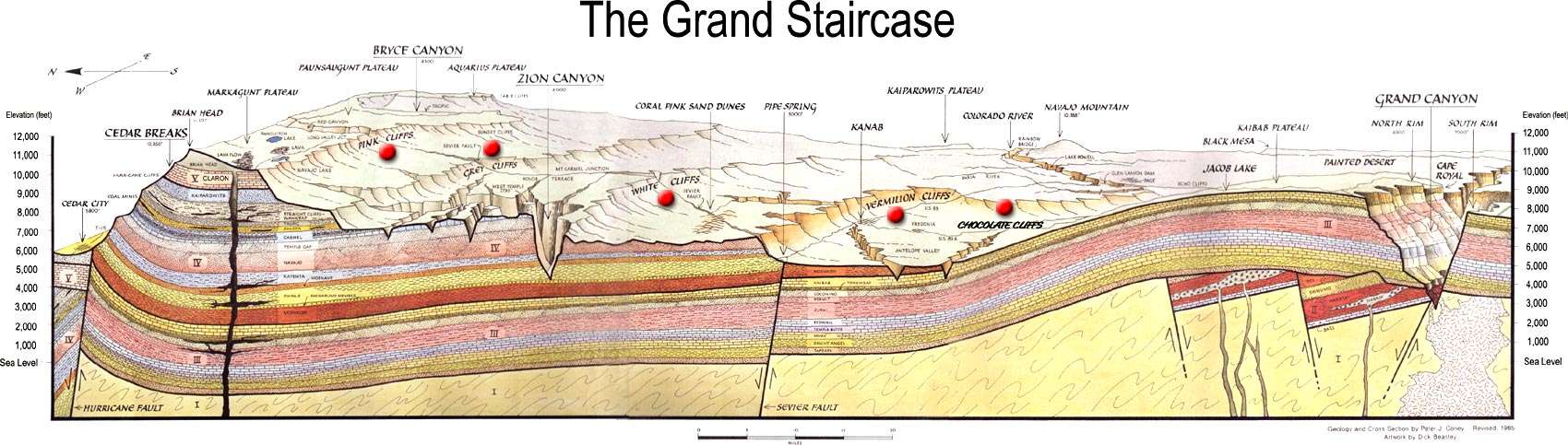

The western part of the Monument is dominated by the Paunsaugunt Plateau and the Paria River, and is adjacent to Bryce Canyon National Park. This section shows the geologic progression of the Grand Staircase.

The center section is dominated by a single long ridge, called Kaiparowits Plateau from the west, and called Fifty-Mile Mountain when viewed from the east. Fifty-Mile Mountain stretches southeast from the town of Escalante to the Colorado River in Glen Canyon. The eastern face of the mountain is a steep, 2200 foot (650 m) escarpment. The western side (the Kaiparowits Plateau) is a shallow slope descending to the south and west.

East of Fifty-Mile Mountain are the Canyons of the Escalante. The Monument is bound by Glen Canyon National Recreation Area on the east and south. The popular hiking, backpacking and canyoneering areas include the Canyons of the Escalante, shared with Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Skutumpah and Cottonwood Roads. Highlights include the slot canyons of Peekaboo, Spooky and Brimstone Canyons, the Devil's Garden, Bull Valley Gorge, Willis Creek, Lick Wash and the backpacking areas of lower Coyote Gulch and of Harris Wash.

The Hole-in-the-Rock Road extends southeast from the town of Escalante, along the base of Fifty-Mile Mountain. It is important in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the settlements of southeast Utah, including Bluff, as well as providing access to the Canyons of the Escalante, and to the flat desert at the base of Fifty Mile Mountain that is used for grazing cattle.

Paleontology

Since 2000, numerous dinosaur fossils over 75 million years old have been found at Grand Staircase-Escalante.

In 2002, a volunteer at Grand Staircase-Escalante discovered a 75-million-year-old dinosaur near the Arizona border. On October 3, 2007, the dinosaur's name, Gryposaurus monumentensis (hook-beaked lizard from the monument) was announced in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. G. monumentensis was at least 30 feet (9.1 m) long and 10 feet (3.0 m) tall, and has a powerful jaw with more than 800 teeth.[3][4] Many of the specimens from the Kaiparowits Formation are reposited at the Natural History Museum of Utah.

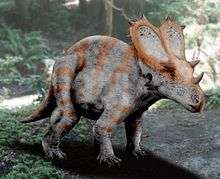

Two ceratopsid (horned) dinosaurs, also discovered at Grand Staircase-Escalante, were introduced by the Utah Geological Survey in 2007. They were uncovered in the Wahweap formation, which is just below the Kaiparowits formation where the duckbill was extracted. They lived about 80 million or 81 million years ago. The two fossils are called the Last Chance skull and the Nipple Butte skull. They were found in 2002 and 2001, respectively.[5] Both were later identified as belonging to Diabloceratops.[6]

In 2013 the discovery of a new species, Lythronax argestes, was announced. It is a tyrannosaur that is approximately 13 mya older than Tyrannosaurus, named for its great resemblance to its descendant. The specimen is available for the public to view at the Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Human history

Humans didn't settle permanently in the area until the Basketmaker III Era, somewhere around AD 500.[7] Both the Fremont and ancestral Puebloan people lived here; the Fremont hunting and gathering below the plateau and near the Escalante Valley, and the ancestral Puebloans farming in the canyons. Both groups grew corn, beans, and squash, and built brush-roofed pithouses and took advantage of natural rock shelters. Ruins and rock art can be found throughout the Monument.

The first record of white settlers in the region dates from 1866, when Captain James Andrus led a group of cavalry to the headwaters of the Escalante River. In 1871 Jacob Hamblin of Kanab, on his way to resupply the second John Wesley Powell expedition, mistook the Escalante River for the Dirty Devil River and became the first Anglo to travel the length of the canyon.

In 1879 the San Juan Expedition crossed through the Monument on their way to a proposed Mormon colony in the far southeastern corner of Utah. Traveling on a largely unexplored route, the group eventually arrived at the 1200-foot (400 m) sandstone cliffs that surrounded Glen Canyon. They found the only breach for many miles in the otherwise vertical cliffs, which they named Hole-in-the-Rock. The narrow, steep, and rocky crevice eventually led to a steep sandy slope in the lower section and eventually down to the Colorado River. With winter settling in, the company decided to go forward, down the crevice, rather than retreat. After six weeks of labor, including excavation and the use of explosives to shift rock, they rigged a pulley system to lower their wagons and animals down the resulting road and off the cliff. There they built a ferry, crossed the river and climbed back out through Cottonwood Canyon on the other side.

Controversy

The Monument was declared in September 1996 at the height of the 1996 presidential election campaign by President Bill Clinton, and was controversial from the moment of creation. The declaration ceremony was held at Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona, and not in the state of Utah. The Utah congressional delegation and state governor were notified only 24 hours in advance. That November, Clinton won Arizona by a margin of 2.2%, and lost Utah to Republican Bob Dole by 21.1%.

Local officials and Congressman Bill Orton (D - UT) objected to the designation of the Monument, questioning whether the Antiquities Act allowed such vast amounts of land to be designated.[8][9] However, United States Supreme Court decisions have long established the president's discretion to protect land under the Antiquities Act, and several lawsuits filed in an effort to overturn the designation were dismissed by federal courts.[10] Monument designation also nixed the Andalex Coal Mine that was proposed for a remote location on the Kaiparowits Plateau.[11]

Wilderness designation for the lands in the Monument had long been sought by environmental groups however designation of the Monument is not the same as Wilderness designation as activities such as grazing are still allowed.

There are contentious issues peculiar to the state of Utah. Certain plots of land were assigned when Utah became a state (in 1896) as School and Institutional Trust Lands (SITLa, a Utah state agency), to be managed to produce funds for the state school system. These lands included scattered plots in the Monument that could no longer be developed. The SITLa plots within the Monument were exchanged for federal lands elsewhere in Utah, plus equivalent mineral rights and $50 million cash by an act of Congress, the Utah Schools and Lands Exchange Act of 1998, supported by Democrats and Republicans, and signed into law as Public Law 105-335 on October 31, 1998.[12]

A more difficult problem is the resolution of United States Revised statute 2477 (R.S. 2477) road claims. R.S. 2477 (Section 8 of the 1866 Mining Act) states: "The right-of-way for the construction of highways over public lands, not reserved for public uses, is hereby granted." The statute was repealed by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976, but the repeal was subject to valid existing rights. A process for resolving disputed claims has not been established, and in 1996, the 104th Congress passed a law which prohibited Clinton-administration RS2477 proposed resolution regulations from taking effect without Congressional approval.[13] The right to maintain and improve the many unpaved roads in the Monument is disputed, with county officials placing county road signs on the roads they claim and occasionally applying bulldozers to grade claimed roads, while the BLM tries to exert control over the same roads. Litigation between the state and federal government over R.S. 2477 and road maintenance in the Monument is an ongoing issue.[14]

See also

- Ancient Pueblo Peoples

- Cottonwood Canyon Road

- Devil's Garden

- Grand Staircase

- Grosvenor Arch

- Kodachrome Basin State Park

- Silvestre Vélez de Escalante

- Utah State Route 12

Footnotes

- 1 2 "National Monument detail table as of April 2012" (PDF). Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "FY 2014 GSENM Manager's Report (PDF file link on park's home page)" (PDF). BLM. 2015-01-25. p. 15. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ↑ Duck-billed dinosaur amazes scientists

- ↑ S. Utah dinosaur had a duck-billed snout -- and 800 teeth

- ↑ Utah's new dino-stars: Discoveries give clues to distant past

- ↑ J. I. Kirkland and D. D. DeBlieux. 2007. New horned dinosaurs from the Wahweap Formation, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, southern Utah. Utah Geological Survey Notes 39(3):4-5

- ↑ Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument. Kane County Utah Office of Tourism and Film Commission. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ↑ Mathew Barrett Gross (2002-02-13). "San Rafael Swell monument proposal could prove that Bush realizes the importance of a fair and public process". Headwaters News, University of Montana. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Davidson, Lee (Sep 27, 1996). "Orton's bill would erase power to declare permanent monument". Deseret News.

- ↑ THE MONUMENTAL LEGACY OF THE ANTIQUITIES ACT OF 1906, Mark Squillace, Georgia Law Review, 2003.

- ↑ Grahame, John D.; Thomas D. Sisk (2002). "Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah (page 3 of 4) Coal Mining vs. Wilderness on the Kaiparowits Plateau". Land Use History of the Colorado Plateau. Northern Arizona University. Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- ↑ "Public Law 105-335". US Government Printing Office. 1998. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- ↑ Gamboa, Anthony (February 6, 2004). "Recognition of R.S. 2477 Rights-of-Way under the Department of the Interior's FLPMA Disclaimer Rules and Its Memorandum of Understanding with the State of Utah, B-300912". US Government Accountability Office. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- ↑ "FY 2014 GSENM Manager's Report (PDF file link on park's home page)" (PDF). BLM. 2015-01-25. pp. 6, 14, 15, 55. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

References

- Paul Larmer (editor), Give and Take: How the Clinton Administration's Public Lands Offensive Transformed the American West (High Country News Books, 2004) ISBN 0-9744485-0-8

- Bureau of Land Management, Grand Staircase-Escalante NM, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Management Plan (U.S. Dept. of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, 1999)

- David Urmann, Trail Guide to Grand Staircase-Escalante (Gibbs Smith, 1999) ISBN 0-87905-885-4

- Robert B. Keiter, Sarah B. George and Joro Walker (editors), Visions of the Grand Staircase-Escalante: Examining Utah's Newest National Monument (Utah Museum of Natural History and Wallace Stegner Center, 1998) ISBN 0-940378-12-4

- Julian Smith, "Moon Handbooks Four Corners" (Avalon Travel Publishing, 2003) ISBN 1-56691-581-3

- Fleischner, Thomas Lowe, Singing Stone: A Natural History of the Escalante Canyons (University of Utah Press, 1999) ISBN 978-0-87480-619-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. |

- Bureau of Land Management: Official Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument website

- Grand Staircase Escalante Partners support for public awareness, interpretive, educational, scientific, scenic, historical, and cultural activities.

- Bashkin, Michael; Stohlgren, Thomas J; Otsuki, Yuka; Lee, Michelle; Evangelista, Paul; Belnap, Jayne (2003). "Soil characteristics and plant exotic species invasions in the Grand Staircase—Escalante National Monument, Utah, USA". Applied Soil Ecology. 22: 67. doi:10.1016/S0929-1393(02)00108-7.

- Doelling, Hellmut H.; Blackett, Robert E.; Hamblin, Alden H.; Powell, J. Douglas; Pollock, Gayle L. (2000). "Geology of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah" (PDF). In Sprinkel, Douglas A.; Chidsey, Thomas C.; Anderson, Paul B. Geology of Utah's Parks and Monuments. Utah Geological Association. ISBN 978-0-9702571-0-9.

- Quigley, Justin James (1999). "Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument: Preservation or Politics?". Journal of Land, Resources, & Environmental Law. 19: 55.

- United States. Congress. House. (1997). Establishing the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument: Oversight Hearing before the Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands of the Committee on Resources, House of Representatives, One Hundred Fifth Congress, First Session, On Establishment ... by President Clinton on September 18, 1996: April 29, 1997—Washington, DC. Washington. D.C: G.P.O.