Jim Corbett National Park

| Jim Corbett National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

Bengal tiger in Corbett National Park | |

| |

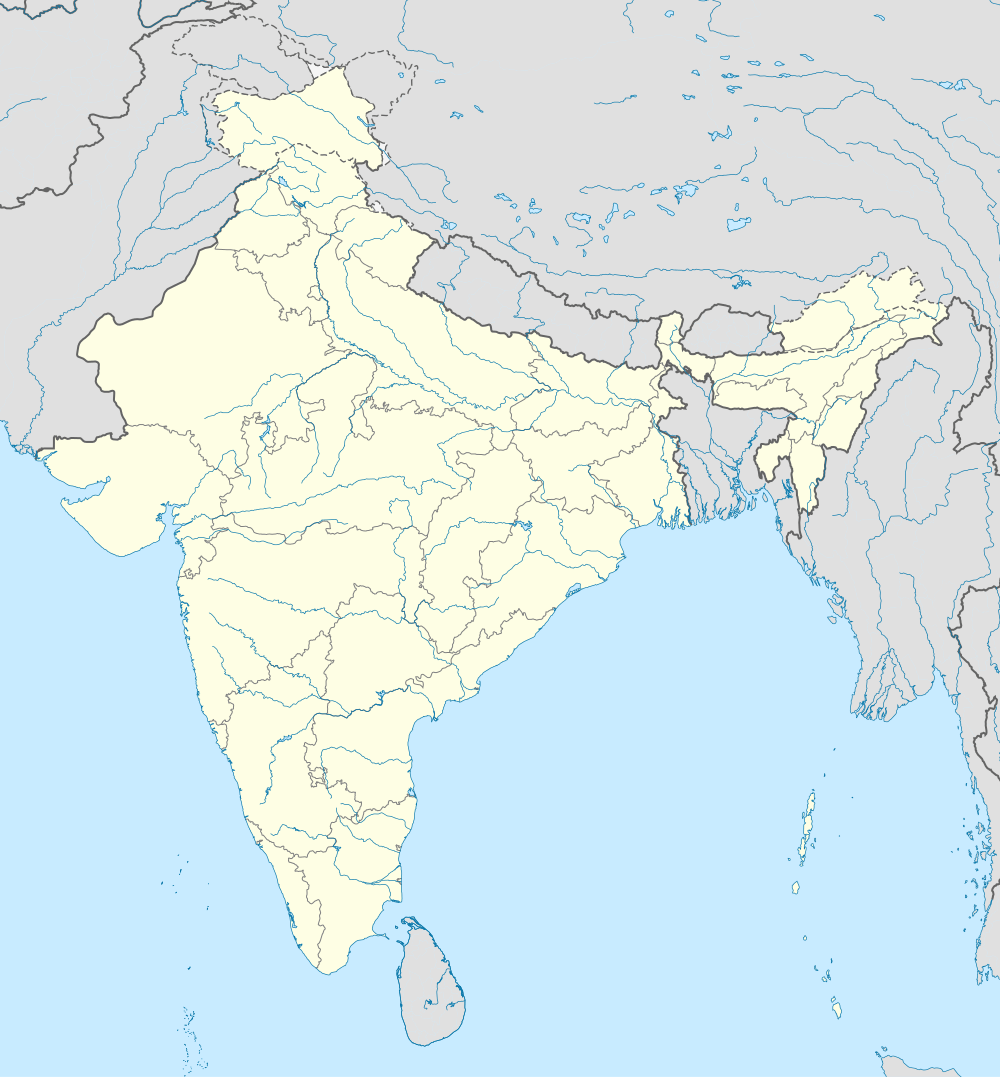

| Location | Nainital, Uttarakhand, India |

| Nearest city | Ramnagar |

| Coordinates | 29°32′55″N 78°56′7″E / 29.54861°N 78.93528°ECoordinates: 29°32′55″N 78°56′7″E / 29.54861°N 78.93528°E |

| Established | 1936 |

| Visitors | 500,000[1] (in 1999) |

| Governing body | Project Tiger, Government of Uttarakhand, Wildlife Warden, Jim Corbett National Park |

| http://corbettonline.uk.gov.in/ | |

Jim Corbett National Park is the oldest national park in India and was established in 1936 as Hailey National Park to protect the endangered Bengal tiger. It is located in Nainital district of Uttarakhand and was named after Jim Corbett who played a key role in its establishment. The park was the first to come under the Project Tiger initiative.[2]

The park has sub-Himalayan belt geographical and ecological characteristics.[3] An ecotourism destination,[4] it contains 488 different species of plants and a diverse variety of fauna.[5][6] The increase in tourist activities, among other problems, continues to present a serious challenge to the park's ecological balance.[7]

Corbett has been a haunt for tourists and wildlife lovers for a long time. Tourism activity is only allowed in selected areas of Corbett Tiger Reserve so that people get an opportunity to see its splendid landscape and the diverse wildlife. In recent years the number of people coming here has increased dramatically. Presently, every season more than 70,000 visitors come to the park.

Corbett National Park comprises 520.8 km2 (201.1 sq mi) area of hills, riverine belts, marshy depressions, grasslands and a large lake. The elevation ranges from 1,300 to 4,000 ft (400 to 1,220 m). Winter nights are cold but the days are bright and sunny. It rains from July to September.

Dense moist deciduous forest mainly consists of sal, haldu, peepal, rohini and mango trees. Forest covers almost 73% of the park, 10% of the area consists of grasslands. It houses around 110 tree species, 50 species of mammals, 580 bird species and 25 reptile species.

History

Some areas of the park were formerly part of the princely state of Tehri Garhwal.[8] The forests were cleared to make the area less vulnerable to Rohilla invaders.[8] The Raja of Tehri formally ceded a part of his princely state to the East India Company in return for their assistance in ousting the Gurkhas from his domain.[8] The Boksas—a tribe from the Terai—settled on the land and began growing crops, but in the early 1860s they were evicted with the advent of British rule.[8]

Efforts to save the forests of the region began in the 19th century under Major Ramsay, the British Officer who was in-charge of the area during those times. The first step in the protection of the area began in 1868 when the British forest department established control over the land and prohibited cultivation and the operation of cattle stations.[9] In 1879 these forests were constituted into a reserve forest where restricted felling was permitted.

In the early 1900s, several Britishers, including E. R. Stevans and E. A. Smythies, suggested the setting up of a national park on this soil. The British administration considered the possibility of creating a game reserve there in 1907.[9] It was only in the 1930s that the process of demarcation for such an area got underway, assisted by Jim Corbett, who knew the area well. A reserve area known as Hailey National Park covering 323.75 km2 (125.00 sq mi) was created in 1936, when Sir Malcolm Hailey was the Governor of United Provinces; and Asia's first national park came into existence.[10] Hunting was not allowed in the reserve, only timber cutting for domestic purposes. Soon after the establishment of the reserve, rules prohibiting killing and capturing of mammals, reptiles and birds within its boundaries were passed.[11]

The reserve was renamed in 1954–55 as Ramganga National Park and was again renamed in 1955–56 as Corbett National Park.[10] The new name honors the well-known author and wildlife conservationist, Jim Corbett,[12] who played a key role in creating the reserve by using his influence to persuade the provincial government to establish it.[11]

The park fared well during the 1930s under an elected administration.[13] But, during the Second World War, it suffered from excessive poaching and timber cutting.[13] Over time, the area in the reserve was increased—797.72 km2 (308.00 sq mi) were added in 1991 as a buffer zone to the Corbett Tiger Reserve.[10] The 1991 addition included the entire Kalagarh forest division, assimilating the 301.18 km2 (116.29 sq mi) area of Sonanadi Wildlife Sanctuary as a part of the Kalagarh division.[10] It was chosen in 1974 as the location for launching Project Tiger, an ambitious and well known wildlife conservation project.[14] The reserve is administered from its headquarters in the district of Nainital.[9]

Corbett National Park is one of the thirteen protected areas covered by the World Wide Fund For Nature under their Terai Arc Landscape Program.[15] The program aims to protect three of the five terrestrial flagship species, the tiger, the Asian elephant and the great one-horned rhinoceros, by restoring corridors of forest to link 13 protected areas of Nepal and India, to enable wildlife migration.[15]

Geography

The park is located between 29°25' and 29°39'N latitude and between 78°44' and 79°07'E longitude.[8] The altitude of the region ranges between 360 m (1,181 ft) and 1,040 m (3,412 ft).[3] It has numerous ravines, ridges, minor streams and small plateaus with varying aspects and degrees of slope.[3] The park encompasses the Patli Dun valley formed by the Ramganga river.[16] It protects parts of the Upper Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests and Himalayan subtropical pine forests ecoregions. It has a humid subtropical and highland climate.

The present area of the reserve is 1,318.54 square kilometres (509.09 sq mi) including 520 square kilometres (200 sq mi) of core area and 797.72 square kilometres (308.00 sq mi) of buffer area. The core area forms the Jim Corbett National Park while the buffer contains reserve forests (496.54 square kilometres (191.72 sq mi)) as well as the Sonanadi Wildlife Sanctuary (301.18 square kilometres (116.29 sq mi)).

The reserve, located partly along a valley between the Lesser Himalaya in the north and the Shivaliks in the south, has a sub-Himalayan belt structure.[3] The upper tertiary rocks are exposed towards the base of the Shiwalik range and hard sandstone units form broad ridges.[3] Characteristic longitudinal valleys, geographically termed Doons, or Duns can be seen formed along the narrow tectonic zones between lineaments.[3]

Climate

The weather in the park is temperate compared to most other protected areas of India.[16] The temperature may vary from 5 °C (41 °F) to 30 °C (86 °F) during the winter and some mornings are foggy.[16] Summer temperatures normally do not rise above 40 °C (104 °F).[16] Rainfall ranges from light during the dry season to heavy during the monsoons.[2]

Flora

A total of 488 different species of plants have been recorded in the park.[5] Tree density inside the reserve is higher in the areas of Sal forests and lowest in the Anogeissus-Acacia catechu forests.[17] Total tree basal cover is greater in Sal dominated areas of woody vegetation.[17] Healthy regeneration in sapling and seedling layers is occurring in the Mallotus philippensis, Jamun and Diospyros tomentosa communities, but in the Sal forests the regeneration of sapling and seedling is poor.[17]

Dense forest inside the park

Dense forest inside the park Grasslands at Jim Corbett National Park

Grasslands at Jim Corbett National Park- Indian elephant herd

River at Corbett

River at Corbett Landscape in the park at the dawn

Landscape in the park at the dawn- Corbett National Park

Fauna

More than 586 species of resident and migratory birds have been categorised, including the crested serpent eagle, blossom-headed parakeet and the red junglefowl — ancestor of all domestic fowl.[6] 33 species of reptiles, seven species of amphibians, seven species of fish and 36 species of dragonflies have also been recorded.[8]

Bengal tigers, although plentiful, are not easily spotted due to the abundance of foliage - camouflage - in the reserve.[2] Thick jungle, the Ramganga river and plentiful prey make this reserve an ideal habitat for tigers who are opportunistic feeders and prey upon a range of animals.[18] The tigers in the park have been known to kill much larger animals such as buffalo and even elephant for food.[6] The tigers prey upon the larger animals in rare cases of food shortage.[6] There have been incidents of tigers attacking domestic animals in times of shortage of prey.[6]

Leopards are found in hilly areas but may also venture into the low land jungles.[6] Small cats in the park include the jungle cat, fishing cat and leopard cat.[6] Other mammals include barking deer, sambar deer, hog deer and chital, sloth and Himalayan black bears, Indian grey mongoose, otters, yellow-throated martens, Himalayan goral, Indian pangolins, and langur and rhesus macaques.[18] Owls and nightjars can be heard during the night.[6]

In the summer, Indian elephants can be seen in herds of several hundred.[6] The Indian python found in the reserve is a dangerous species, capable of killing a chital deer.[6] Local crocodiles and gharials were saved from extinction by captive breeding programs that subsequently released crocodiles into the Ramganga river.[6]

- Spotted deer at Corbett

Sambar deer

Sambar deer Elephant

Elephant Tigress at Corbett National Park

Tigress at Corbett National Park Tawny fish owl

Tawny fish owl Golden jackal

Golden jackal_at_Jim_Corbett_National_Park%2C_Uttarakhand.jpg) Little green bee-eaters at Corbett National Park

Little green bee-eaters at Corbett National Park Pallas's fish eagle

Pallas's fish eagle

Ecotourism

Though the main focus is protection of wildlife, the reserve management has also encouraged ecotourism.[10] In 1993, a training course covering natural history, visitor management and park interpretation was introduced to train nature guides.[10] A second course followed in 1995 which recruited more guides for the same purpose.[10] This allowed the staff of the reserve, previously preoccupied with guiding the visitors, to carry out management activities uninterrupted.[10] Additionally, the Indian government has organised workshops on ecotourism in Corbett National Park and Garhwal region to ensure that the local citizens profit from tourism while the park remains protected.[10]

patil & Joshi (1997) consider summer (April–June) to be the best season for Indian tourists to visit the park while recommending the winter months (November–January) for foreign tourists.[19] According to Riley & Riley (2005): "Best chances of seeing a tiger to come late in the dry season- April to mid-June-and go out with mahouts and elephants for several days."[6]

As early as 1991, the Corbett National Park played host to 3237 tourist vehicles carrying 45,215 visitors during the main tourist seasons between 15 November and 15 June.[4] This heavy influx of tourists has led to visible stress signs on the natural ecosystem.[4] Excessive trampling of soil due to tourist pressure has led to reduction in plant species and has also resulted in reduced soil moisture.[4] The tourists have increasingly used fuel wood for cooking.[4] This is a cause of concern as this fuel wood is obtained from the nearby forests, resulting in greater pressure on the forest ecosystem of the park.[4] Additionally, tourists have also caused problems by making noise, littering and causing disturbances in general.[20]

In 2007, young naturalist and photographer – Kahini Ghosh Mehta – took up the challenge of promoting healthy tourism in Corbett National Park and made the first comprehensive travel guide on Corbett. The film titled – Wild Saga of Corbett – showcases how tourists can contribute in their own small way in conservation efforts.

Other attractions

- Dhikala is a well-known destination in the park and situated at the fringes of Patli Dun valley. There is a rest house, which was built hundred of years ago. Kanda ridge forms the backdrop, and from Dhikala, one can enjoy the spectacular natural beauty of the valley.

- Jeep Safari is the most convenient way to travel within the national park; jeeps can be rented for park trips from Ramnagar.[21]

- Treks: tourists are not allowed to walk inside the park, but only to go trekking around the park in the company of a guide. The winter season is cold, so tourists should make proper arrangements for their clothing, if they are traveling in the winter season.

- Walking Safaris are possible in the buffer zone areas - and very rewarding with Corbett having a very healthy and lush, rich buffer zone around; look for lodges around with trained staff for the same.[22]

- Kalagarh Dam is dam located in the south-west of the wildlife sanctuary. This is one of the best places for a bird watching tour. Lots of migratory waterfowl comes here in the winters.

- Corbett Falls is a 20 m (66 ft) water fall situated 25 km (16 mi) from Ramnagar, and 4 km (2.5 mi) from Kaladhungi, on the Kaladhungi–Ramnagar highway. The water falls is surrounded by dense forests and pin drop silence.[23]

- Garjiya Devi Temple is sacred to Garjiya Devi and is mostly visited by the traveller during the Kartik Poornima (November – December). It is a prominent temple located on the bank of river Kosi, amidst the hilly terrains of Uttarakhand, nearby Garjiya village, at a distance of 14 km. from Ramnagar, Uttarakhand, India.[24]

Location

Corbett National Park is situated in Ramanagar in the district of Nainital, Uttarakhand.

Area: 521 km2

Route: The town of Ramnagar is the headquarters of Corbett Tiger Reserve. There are overnight trains available from Delhi to Ramnagar. Also, there are trains from Varanasi via Lucknow and Allahabad via Kanpur to Ramnagar. Reaching Ramnagar, one can hire a taxi to reach the park and Dhikala.

Ramnagar is also well connected by road with Kanpur, Lucknow, Bareilly, Nainital, Ranikhet, Haridwar, Dehradun and New Delhi. One can also drive from Delhi (295 km) via Gajraula, Moradabad, Kashipur to reach Ramnagar. A direct train to Ramnagar runs from New Delhi. Alternatively, one can come up to Haldwani/Kashipur/Kathgodam and come to Ramnagar by road.

Best Time to Visit: Mid-November to Mid-June.

Challenges

Past

A major incident in the history of the reserve followed the construction of a dam at the Kalagarh river and the submerging of 80 km2 (31 sq mi) of prime low lying riverine area.[10] The consequences ranged from local extinction of swamp deer to a massive reduction in hog deer population.[10] The reservoir formed due to the submerging of land has also led to an increase in aquatic fauna and has additionally served as a habitat for winter migrants.[10]

Two villages situated on the southern boundary were shifted to the Firozpur–Manpur area situated on Ramnagar–Kashipur highway during 1990–93; the vacated areas were designated as buffer zones.[25] The families in these villages were mostly dependent on forest products.[25] With the passage of time, these areas began to show signs of ecological recovery.[25] Vines, herbs, grasses and small trees began to appear, followed by herbaceous flora, eventually leading to natural forest type.[25] It was observed that grass began to grow on the vacated agricultural fields and the adjoining forest areas started recuperating.[25] By 1999–2002 several plant species emerged in these buffer zones.[25] The newly arisen lush green fields attracted grass eating animals, mainly deer and elephants, who slowly migrated towards these areas and even preferred to stay there throughout the monsoon.[25]

There were 109 cases of poaching recorded in 1988–89.[26] This figure dropped to 12 reported cases in 1997–98 .[10]

In 1985 David Hunt, a British ornithologist and birdwatching tour guide, was killed by a tiger in the park.

Present

The habitat of the reserve faces threats from invasive species such as the exotic weeds Lantana, Parthenium and Cassia.[10] Natural resources like trees and grasses are exploited by the local population while encroachment of at least of 13.62 ha (0.05 sq mi) by 74 families has been recorded.[10]

The villages surrounding the park are at least 15–20 years old and no new villages have come up in the recent past.[27] The increasing population growth rate and the density of population within 1 km (0.62 mi) to 2 km (1.24 mi) from the park present a challenge to the management of the reserve.[27] Incidents of killing cattle by tigers and leopards have led to acts of retaliation by the local population in some cases.[10] The Indian government has approved the construction of a 12 km (7.5 mi) stone masonry wall on the southern boundary of the reserve where it comes in direct contact with agricultural fields.[10]

In April 2008, the National Conservation Tiger Authority (NCTA) expressed serious concern that protection systems have weakened, and poachers have infiltrated into this park. Monitoring of wild animals in the prescribed format has not been followed despite advisories and observations made during field visits. Also the monthly monitoring report of field evidence relating to tigers has not been received since 2006. NCTA said that in the "absence of ongoing monitoring protocol in a standardised manner, it would be impossible to forecast and keep track of untoward happenings in the area targeted by poachers." A cement road has been built through the park against a Supreme Court order. The road has become a thoroughfare between Kalagarh and Ramnagar. Constantly increasing vehicle traffic on this road is affecting the wildlife of crucial ranges like Jhirna, Kotirau and Dhara. Additionally, the Kalagarh irrigation colony that takes up about 5 square kilometres (1.9 sq mi) of the park is yet to be vacated despite a 2007 Supreme Court order.[28]

As of 10 February 2014, nine local villagers are reported to have been killed by tigers originating from Jim Corbett National Park [29] wildlife sanctuary opened a new zone for tourists stretched across 521 km2[30]

Ecosystem Valuation

An economic assessment study of Jim Corbett Tiger Reserve estimated its annual flow benefits to be 14.7 billion (1.14 lakh / hectare). Important ecosystem services included gene-pool protection (10.65 billion), provisioning of water to downstream districts of Uttar Pradesh (1.61 billion), water purification services to the city of New Delhi (550 million), employment for local communities (82 million), provision of habitat and refugia for wildlife (274 million) and sequestration of carbon (214 million).[31]

See also

- Indian wildlife portal on Wikipedia

- Indomalaya ecozone

- Critically endangered species

- Leopard of Rudraprayag

- Champawat Tiger

- Rajaji National Park

- Man-Eaters of Kumaon and other literary references to Nainital

- Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education

- Arid Forest Research Institute

- Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education

Notes

- ↑ Sinha, B. C., Thapliyal, M. and K. Moghe. "An Assessment of Tourism in Corbett National Park". Wildlife Institute of India. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- 1 2 3 Riley & Riley 2005: 208

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tiwari & Joshi 1997: 210

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tiwari & Joshi 1997: 309

- 1 2 Pant 1976

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Riley & Riley 2005: 210

- ↑ Tiwariji & Joshiji 1997: 309–311

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 UNEP 2003

- 1 2 3 Tiwari & Joshi 1997: 208

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Corbett National Park (Project Tiger Directorate)

- 1 2 Rangarajan 2006: 72

- ↑ Jim Corbett National Park – History

- 1 2 Rangarajan 2006: 78

- ↑ Tiwari & Joshi 1997: 108

- 1 2 Drayton 2004

- 1 2 3 4 Tiwari & Joshi 1997: 286

- 1 2 3 Singh et al. 1995

- 1 2 Riley & Riley 2005: 208–210

- ↑ Tiwari & Joshi 1997: 298

- ↑ Tiwari & Joshi 1997: 311

- ↑ http://expertbulletin.com/jim-corbett-national-park/

- ↑ https://www.google.co.in/search?q=corbett+walking+safaris

- ↑ http://www.nainitaltourism.com/corbett_water_fall.html

- ↑ http://www.corbett-national-park.com/places-near-corbett.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rao 2004

- ↑ Tiwari & Joshi 1997: 269

- 1 2 Tiwari & Joshi 1997: 263

- ↑ The Pioneer

- ↑ http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/environment/flora-fauna/Another-Corbett-death-another-tiger-on-the-prowl/articleshow/30132656.cms?

- ↑ http://www.dailymail.co.uk/indiahome/indianews/article-2856769/Jim-Corbett-National-Park-park-unveils-new-wildlife-zone.html

- ↑ (PDF) http://www.iifm.ac.in/sites/default/files/Newspdf/IIFM-NTCA-REPORT.compressed-min.pdf. Retrieved 14 August 2016. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

References

- Riley, Laura; William Riley (2005). Nature's Strongholds: The World's Great Wildlife Reserves. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12219-9.

- Singh, Ashok; Reddy, V. S.; Singh, J. S. "Analysis of woody vegetation of Corbett National Park, India". Vegetatio. 120 (1 / September 1995): 69–79.

- Tiwari, P. C.; Joshi, Bhagwati, eds. (January 1997). Wildlife in the Himalayan Foothills: Conservation and Management. Indus Publishing Company. ISBN 81-7387-066-7.

- "Corbett National Park (Project Tiger Directorate)". Project Tiger Directorate, Ministry of Environment, Government of India. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- Rangarajan, M. (2006). India's Wildlife History: an Introduction. Orient Longman. ISBN 81-7824-140-4.

- UNEP (2003). "World Database on Protected Areas, India, Corbett National Park". UNEP WCMC. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- Drayton, F. (2004). "Terai Arc Landscape in India" (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- Pant, P.C. (1976). "Plants of Corbett National Park, Uttar Pradesh". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 73: 287–295.

- Rao, R.S.P. "Secondary succession in the buffer zone of Corbett Tiger Reserve, Uttaranchal". Current Science. Indian Academy of Sciences. 87 (4, 25 August 2004.).

- The Pioneer (18 May 2008). "Trouble in Paradise". The Pioneer. CMYK Printech Ltd. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

Further reading

- Corbett, Jim (January 1985). Man-Eaters of Kumaon. Buccaneer Books, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89966-574-0.

- Corbett, Jim; Nayak, Prashanto Kumar (July 2004). Oxford India Illustrated Corbett. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-566874-2.

- Durga Charan Kala (1979). Jim Corbett of Kumaon. Ravi Dayal Publishers.

- Martin Booth (1986). Carpet Sahib: A Life of Jim Corbett. Constable. ISBN 978-0-09-467400-4.

- Miriam Davidson (1988). Convictions of the Heart: Jim Corbett and the Sanctuary Movement. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1034-4.

- Werling, T. (1998). Jim Corbett: Master of the Jungle. Safari Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-57157-104-5.

- Jaleel, J. A. (2001). Under the Shadow of Man-eaters: The Life and Legend of Jim Corbett of Kumaon. Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-2020-2.

- Khati, A. S. (2003). Jim Corbett of India: Life & Legend of a Messiah. Pelican Creations International. ISBN 978-81-86738-10-8.

- Johnsingh, A. J. T. (2004). On Jim Corbett's Trail and Other Tales from Tree-tops. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-7824-081-7.

- Gupta, Reeta Dutta (2006). Jim Corbett : The Hunter Conservationist. Rupa & Company. ISBN 978-81-291-0893-7.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Corbett National Park. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jim Corbett National Park. |

- Corbett Tiger Reserve — official website

- Map of the park provided by Project Tiger Directorate, Ministry of Environment, Govt of India.

- Expert Bulletin

- "Corbett National Park." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 12 October 2007

- "Corbett National Park," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. (Archived 2009-10-31)