Maratha

| Maratha मराठा | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Religions | | ||

| Languages | Marathi and Marathi dialects | ||

| Populated States | Major: Maharashtra Minor: Goa, Gujarat, Karnataka, Telangana, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh. | ||

The Maratha (IPA: [ˈməraʈa]; archaically transliterated as Marhatta or Mahratta) is a group of castes in India found predominantly in the state of Maharashtra. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, "Marathas are people of India, famed in history as yeoman warriors and champions of Hinduism."[1] They reside primarily in the Indian state of Maharashtra.[1]

Robert Vane Russell, an untrained ethnologist of the British Raj period, basing his research largely on Vedic literature,[2] wrote that the Marathas are subdivided into 96 different clans, known as the 96 Kuli Marathas or 'Shahānnau Kule'[3] Shahannau means 96 in Marathi. The general body of lists are often at great variance with each other.[4]

History

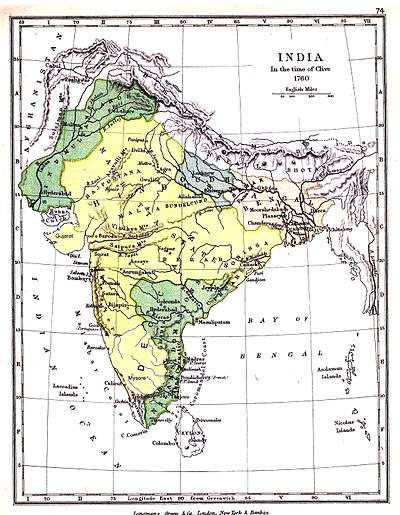

The term "Maratha" originally referred to the speakers of Marathi language. In the 17th century, it emerged as a designation for soldiers serving in the armies of Deccan sultanates (and later Shivaji).[5] A number of Maratha warriors, including Shivaji's father, Shahaji, originally served the various Deccan sultanates.[6] By the mid-1660s, Shivaji had established an independent Maratha kingdom.[7] After his death, the kingdom expanded into a vast empire under the Peshwas, stretching from central India [8] in the south, to Peshawar[9] (in modern-day Pakistan) on the Afghanistan border in the north, and with expeditions to Bengal in the east. By the 19th century, the Empire had become a Confederacy of individual states controlled by Maratha chiefs such as Gaekwads of Baroda, the Holkars of Indore, the Scindias of Gwalior, the Puars of Dhar & Dewas, and Bhonsles of Nagpur. The Confederacy remained the pre-eminent power in India until their defeat by the British East India Company in the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818).[10]

By 19th century, the term "Maratha" had several interpretations in the British administrative records. In the Thane District Gazetteer of 1882, the term was used to denote elite layers within various castes: for example, The upper-class "Marathas proper" (comprising 96 clans) claimed Rajput descent with Kshatriya status, and included princes, officers and landowners.[11][12] Some of the Maratha clans claiming Rajput descent include Bhonsales (from Sisodias),[13] Chavans (from Chauhans),[14] and Pawar (from Parmar).[15] "Maratha-Agri" within Agri caste, "Maratha-Koli" within Koli caste and so on.[5] In the Pune District, the words Kunbi and Maratha had become synonymous, giving rise to the Maratha-Kunbi caste complex.[16] The Pune District Gazetteer of 1882 divided the Kunbis into two classes: Marathas and other Kunbis.[5] The 1901 census listed three groups within the Maratha-Kunbi caste complex: "Marathas proper", "Maratha Kunbis" and "Konkani Marathas".[17] The Kunbi class comprised agricultural workers and soldiers.

Gradually, the term "Maratha" came to denote an endogamous caste.[5] 1900 onwards, the Satyashodhak Samaj movement defined the Marathas as a broader social category of non-Brahmin groups.[18] These non-Brahmins gained prominence in Indian National Congress during the Indian independence movement. In independent India, these Marathas became the dominant political force in the newly formed state of Maharashtra.[19]

Internal diaspora

The empire also resulted in the voluntary relocation of substantial numbers of Maratha and other Marathi-speaking people outside Maharashtra, and across a big part of India. Today several small but significant communities descended from these emigrants live in the north, south and west of India. These descendant communities tend often to speak the local languages, although many also speak Marathi in addition. Notable Maratha families outside Maharashtra include Scindia of Gwalior, Gaekwad of Baroda, Holkar of Indore, Puar of Dewas & Dhar, Ghorpade of Mudhol, and Bhonsle of Nagpur.[20]

Varna status

The varna of the Maratha is a contested issue, with arguments for their being of the Kshatriya (warrior) varna, and others for their being of peasant origins. This issue was the subject of antagonism between the Brahmins and Marathas, dating back to the time of Shivaji, but by the late 19th century moderate Brahmins were keen to ally with the influential Marathas of Mumbai in the interests of Indian independence from Britain. These Brahmins supported the Maratha claim to Kshatriya status, but their success in this political alliance was sporadic and fell apart entirely following independence in 1947.[21]

Political participation

Marathas have dominated the state politics of Maharashtra since its inception in 1960. Since then, Maharashtra has witnessed heavy presence of Maratha ministers or officials in the Maharashtra state government, local municipal commissions, and panchayats, although Marathas comprise only around 25 per cent of the state population.[22][23] 10 out of 16 chief ministers of Maharashtra hailed from the Maratha community as of 2012.[24]

Military service

Beginning early in the 20th century, the British recognised Maratha as a martial race.[25] Earlier listings of martial races had often excluded them, with Lord Roberts, commander-in-chief of the Indian Army 1885–1893, stating the need to substitute "more warlike and hardy races for the Hindusthani sepoys of Bengal, the Tamils and Telugus of Madras and the so-called Marathas of Bombay."[26] Historian Sikata Banerjee notes a dissonance in British military opinions of the Maratha, wherein the British portrayed them as both "formidable opponents" and yet not "properly qualified" for fighting, criticising the Maratha guerrilla tactics as an improper way of war. Banerjee cites an 1859 statement as emblematic of this disparity:

There is something noble in the carriage of an ordinary Rajput, and something vulgar in that of the most distinguished Mahratta. The Rajput is the most worthy antagonist, the Mahratta the most formidable enemy.[27]

The Maratha Light Infantry regiment is one of the "oldest and most renowned" regiments of the Indian Army.[28] Its First Battalion, also known as the Jangi Paltan ("Warrior Platoon"),[29] traces its origins to 1768 as part of the Bombay Sepoys. The battle cry of Maratha Light Infantry is Bol Shri Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj ki Jai! ("Hail Victory to Emperor Shivaji!") in tribute to the Maratha sovereign.

See also

- List of Maratha dynasties and states

- List of notable Maratha People

- Thanjavur Marathi people

- Maratha People in Uttar Pradesh

References

- 1 2 "Maratha (people)". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter. The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 240–242. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- ↑ Russell, Robert Vane (1916). Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India. 4. Lal, Rai Bahadur Hira. London: Macmillan & Co. pp. 201–203. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ O'Hanlon, Rosalind (2002). Caste, Conflict and Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-52152-308-0. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Hansen 2001, p. 31.

- ↑ Gordon, Stewart N. (1993). The Marathas 1600–1818. The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-52126-883-7.

Second, we have that Marathas regularly served in the armies of the Muslim Deccan kingdoms.

- ↑ Pearson, M. N. (February 1976). "Shivaji and the Decline of the Mughal Empire". The Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies. 35 (2): 221–235. doi:10.2307/2053980. JSTOR 2053980.

- ↑ Mehta, J. L. Advanced study in the history of modern India 1707–1813

- ↑ Alexander Mikaberidze (31 July 2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-1-59884-337-8. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ Chhabra, G.S. (2005) [1971]. Advanced Study in the History of Modern India. Lotus Press. ISBN 81-89093-06-1.

- ↑ Pereira 2008, p. 65.

- ↑ Haynes 1992, p. 65.

- ↑ Singh 1998, p. 2211.

- ↑ The Illustrated Weekly of India Volume 92, Part 2. Bennett, Coleman & Company. 1971. p. 7.

- ↑ A. Aiyappan; L. K. Bala Ratnam (1956). Society in India. Social Sciences Association. p. 41.

- ↑ O'Hanlon 2002, p. 45.

- ↑ O'Hanlon 2002, p. 47.

- ↑ Hansen 2001, p. 32.

- ↑ Hansen 2001, p. 34.

- ↑ "History of Medieval India". google.com. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ↑ Kurtz, Donald V. (1994). Contradictions and Conflict: A Dialectical Political Anthropology of a University in Western India. Leiden: Brill. p. 63. ISBN 978-9-00409-828-2.

- ↑ Mishra, Sumita (2000). Grassroot Politics in India. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 27. ISBN 9788170997320.

- ↑ Dhanagare, D. N. (1995). "The Class Character and Politics of the Farmers' Movement in Maharashtra during the 1980s". In Brass, Tom. New Farmers' Movements in India. Ilford: Routledge/Frank Cass. p. 80. ISBN 9780714646091.

- ↑ Economic and Political Weekly: January 2012 First Volume Pg 45

- ↑ Deshpande, Prachi (2007) [2006 (Permanent Black]. Creative Pasts: Historical Memory And Identity in Western India, 1700–1960. New York & Chichester: Columbia University Press. p. 189. ISBN 9780231124867. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ Samanta, Amiya K. (2000). Gorkhaland Movement: A Study in Ethnic Separatism. New Delhi: APH Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 9788176481663. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ Banerjee, Sikata (2005). Make Me a Man!: Masculinity, Hinduism, and Nationalism in India. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780791463673. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ Frank Edwards (2003). The Gaysh: A History of the Aden Protectorate Levies 1927–61 and the Federal Regular Army of South Arabia 1961–67. Helion & Company Limited. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-1-874622-96-3. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ Roger Perkins (1994). Regiments: Regiments and Corps of the British Empire and Commonwealth, 1758–1993 : a Critical Bibliography of Their Published Histories. Roger Perkins. ISBN 978-0-9506429-3-2. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

Further reading

- Asher, Catherine B.; Talbot, Cynthia (2006). India Before Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Bayly, Christopher Alan (1990). Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38650-0. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Hansen, Thomas Blom (2001). Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08840-3.

- Haynes, Douglas E. (1992). Contesting Power: Resistance and Everyday Social Relations in South Asia. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07585-6.

- Ludden, David (2013). India and South Asia: A Short History. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-85168-936-1.

- Ludden, David (1999). An Agrarian History of South Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36424-9. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (28 September 2006). A Concise History of Modern India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45887-0. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- O'Hanlon, Rosalind (2002). Caste, Conflict and Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52308-0.

- Pereira, A B de Bragnanca (2008). Ethnography of Goa, Daman and Diu. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-93-5118-208-5.

- Robb, Peter (2011). A History of India. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-34549-2.

- Singh, K. S. (1998). India's Communities. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-563354-2.

- Stein, Burton (2010). A History of India. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Wink, André (2007). Land and Sovereignty in India: Agrarian Society and Politics Under the Eighteenth-Century Maratha Svarājya. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-05180-4. Retrieved 20 October 2013.