Douglas fir

| Douglas-fir | |

|---|---|

| |

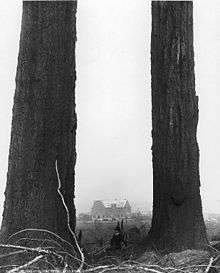

| Coast Douglas firs in Marysville, Washington | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Genus: | Pseudotsuga |

| Species: | P. menziesii |

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | |

| |

Pseudotsuga menziesii, commonly known as Douglas fir or Douglas-fir, is an evergreen conifer species native to western North America.

Naming

The common name honors David Douglas, a Scottish botanist and collector who first reported the extraordinary nature and potential of the species. The common name is misleading since it is not a true fir, i.e., not a member of the genus Abies. For this reason the name is often written as Douglas-fir (a name also used for the genus Pseudotsuga as a whole).[2]

The specific epithet, menziesii, is after Archibald Menzies, a Scottish physician and rival naturalist to David Douglas. Menzies first documented the tree on Vancouver Island in 1791. Colloquially, the species is also known simply as Doug-fir or as Douglas pine (although the latter common name may also refer to Pinus douglasiana).

One Coast Salish name for the tree, used in the Halkomelem language, is lá:yelhp.[3]

Distribution

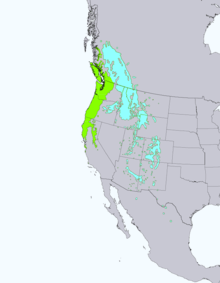

One variety, coast Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii), grows in the coastal regions, from west-central British Columbia southward to central California. In Oregon and Washington, its range is continuous from the eastern edge of the Cascades west to the Pacific Coast Ranges and Pacific Ocean. In California, it is found in the Klamath and California Coast Ranges as far south as the Santa Lucia Range, with a small stand as far south as the Purisima Hills in Santa Barbara County.[4][5] In the Sierra Nevada, it ranges as far south as the Yosemite region. It occurs from near sea level along the coast to 1,800 m (5,900 ft) above sea level in the mountains of California.

Further inland, coast Douglas fir is replaced by another variety, Rocky Mountain or interior Douglas fir (P. menziesii var. glauca). Interior Douglas fir intergrades with coast Douglas fir in the Cascades of northern Washington and southern British Columbia, and from there ranges northward to central British Columbia and southeastward to the Mexican border, becoming increasingly disjunct as latitude decreases and altitude increases. Mexican Douglas fir (P. lindleyana), which ranges as far south as Oaxaca, is often considered a variety of P. menziesii.

Description

Coast Douglas fir is currently the second-tallest conifer in the world (after coast redwood).[6] Extant coast Douglas fir trees 60–75 m (195–245 ft) or more in height and 1.5–2 m (4.9–6.6 ft) in diameter are common in old growth stands,[7] and maximum heights of 100–120 m (330–395 ft) and diameters up to 4.5–5.5 m (15–18 ft) have been documented.[8] The tallest living specimen is the "Doerner Fir", previously known as the Brummit Fir, 99.8 m (327.3 ft) tall,[9] at East Fork Brummit Creek in Coos County, Oregon, the stoutest is the "Queets Fir", 4.85 m (15 ft 11 in) in diameter, in the Queets River valley of Olympic National Park in Washington. Douglas firs commonly live more than 500 years and occasionally more than 1,000 years.[10]

The bark on young trees is thin, smooth, and gray,[11] and contains numerous resin blisters. On mature trees, it is thick and corky.[11] The shoots are brown to olive-green, turning gray-brown with age, smooth, though not as smooth as fir shoots, and finely pubescent with short, dark hairs. The buds are a very distinctive, narrow, conic shape, 4–8 mm (5⁄32–5⁄16 in) long, with red-brown bud scales. The leaves are spirally arranged, but slightly twisted at the base to lie flattish on either side of the shoot, needle-like, 2–3.5 cm (3⁄4–1 3⁄8 in) long, green above with no stomata, and with two whitish stomatal bands below. Unlike the Rocky Mountain Douglas fir, coast Douglas fir foliage has a noticeable sweet fruity-resinous scent,[11] particularly if crushed.

The mature female seed cones are pendulous, 5–8 cm (2–3 1⁄4 in) long,[11] 2–3 cm (3⁄4–1 1⁄8 in) wide when closed, opening to a 4 cm (1.6 in) width. They are produced in spring, green at first, maturing orange-brown in the autumn 6–7 months later. The seeds are 5–6 mm (3⁄16–1⁄4 in) long and 3–4 mm (1⁄8–5⁄32 in) wide, with a 12–15-mm wing. The male (pollen) cones are 2–3 cm (3⁄4–1 1⁄8 in) long, dispersing yellow pollen in spring.

In forest conditions, old individuals typically have a narrow, cylindric crown beginning 20–40 m (65–130 ft) above a branch-free trunk. Self-pruning is generally slow and trees retain their lower limbs for a long period. Young, open-grown trees typically have branches down to near ground level. It often takes 70–80 years for the trunk to be clear to a height of 5 m (15 ft) and 100 years to be clear to a height of 10 m (35 ft).

Appreciable seed production begins at 20–30 years in open-grown coast Douglas fir. Seed production is irregular; over a 5–7 year period, stands usually produce one heavy crop, a few light or medium crops, and one crop failure. Even during heavy seed-crop years, only about 25% of trees in closed stands produce an appreciable number of cones. Each cone contains around 25 to 50 seeds. Seed size varies; average number of cleaned seeds varies from 70 to 88 per g (32,000–40,000 per lb). Seeds from the northern portion of its range tend to be larger than seeds from the south.

Ecology

The rooting habit of coast Douglas fir is not particularly deep, with the roots tending to be shallower than those of same-aged ponderosa pine, sugar pine, or California incense-cedar, though deeper than Sitka spruce. Some roots are commonly found in organic soil layers or near the mineral soil surface. Douglas-fir prefers acidic or neutral soils.[12] However, Douglas fir exhibits considerable morphological plasticity, and on drier sites coast Douglas fir will generate deeper taproots. Interior Douglas fir exhibits even greater plasticity, occurring in stands of interior temperate rainforest in British Columbia, as well as at the edge of semi-arid sagebrush steppe throughout much of its range, where it generates even deeper taproots than coast Douglas fir is capable.

Douglas fir snags are abundant in forests older than 100–150 years and provide cavity-nesting habitat for numerous forest birds. Mature or "old-growth" Douglas fir forest is the primary habitat of the red tree vole (Arborimus longicaudus) and the spotted owl (Strix occidentalis). Home range requirements for breeding pairs of spotted owls are at least 400 ha (4 square kilometres, 990 acres) of old-growth. Red tree voles may also be found in immature forests if Douglas fir is a significant component. This animal nests almost exclusively in the foliage of Douglas fir trees. Nests are located 2–50 metres (5–165 ft) above the ground. The red vole's diet consists chiefly of Douglas fir needles. A parasitic plant sometimes utilizing P. menziesii is Douglas-fir dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium douglasii).

Its seedlings are not a preferred browse of black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus) and elk (Cervus canadensis), but can be an important food source for these animals during the winter when other preferred forages are lacking. In many areas, Douglas fir needles are a staple in the spring diet of blue grouse (Dendragapus). In the winter, New World porcupines primarily eat the inner bark of young conifers, among which they prefer Douglas fir.

The leaves are also used by the woolly conifer aphid Adelges cooleyi; this 0.5 mm long sap-sucking insect is conspicuous on the undersides of the leaves by the small white "fluff spots" of protective wax that it produces. It is often present in large numbers, and can cause the foliage to turn yellowish from the damage in causes. Exceptionally, trees may be partially defoliated by it, but the damage is rarely this severe. Among Lepidoptera, apart from some that feed on Pseudotsuga in general (see there) the gelechiid moths Chionodes abella and C. periculella as well as the cone scale-eating tortrix moth Cydia illutana have been recorded specifically on P. menziesii.

Douglas fir seeds are an extremely important food for small mammals. Mice, voles, shrews, and chipmunks consumed an estimated 65 percent of a Douglas fir seed crop following dispersal in western Oregon. The Douglas squirrel (Tamiasciurus douglasii) harvests and caches great quantities of Douglas fir cones for later use. They also eat mature pollen cones, developing inner bark, terminal shoots, and tender young needles. The seeds are also important in the diets of several seed-eating birds. These include most importantly American sparrows (Emberizidae) – dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis), song sparrow (Melospiza melodia), golden-crowned sparrow (Zonotrichia atricapilla) and white-crowned sparrow (Z. leucophrys) – and true finches (Fringillidae) – pine siskin (Carduelis pinus), purple finch ("Carpodacus" purpureus), and the Douglas fir red crossbill (Loxia curvirostra neogaea) which is uniquely adapted to foraging for P. menziesii seeds.

The coast Douglas fir variety is the dominant tree west of the Cascade Mountains in the Pacific Northwest, occurring in nearly all forest types, competes well on most parent materials, aspects, and slopes. Adapted to a moist, mild climate, it grows larger and faster than Rocky Mountain Douglas fir. Associated trees include western hemlock, Sitka spruce, sugar pine, western white pine, ponderosa pine, grand fir, coast redwood, western redcedar, California incense-cedar, Lawson's cypress, tanoak, bigleaf maple and several others. Pure stands are also common, particularly north of the Umpqua River in Oregon.

Shrub associates in the central and northern part of coast Douglas fir's range include vine maple (Acer circinatum), salal (Gaultheria shallon), Pacific rhododendron (Rhododendron macrophyllum), Oregon-grape (Mahonia aquifolium), red huckleberry (Vaccinium parvifolium), and salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis). In the drier, southern portion of its range shrub associates include California hazel (Corylus cornuta var. californica), oceanspray (Holodiscus discolor), creeping snowberry (Symphoricarpos mollis), western poison-oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum), ceanothus (Ceanothus spp.), and manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.). In wet coastal forests, nearly every surface of old-growth coast Douglas fir is covered by epiphytic mosses and lichens.

Poriol is a flavanone, a type of flavonoid, produced by P. menziesii in reaction to infection by Poria weirii.[13]

Forest succession

The shade-intolerance of Douglas fir plays a large role in the forest succession of lowland old growth rainforest communities of the Pacific Northwest. While mature stands of lowland old-growth rainforest contain many western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) seedlings, and some western redcedar (Thuja plicata) seedlings, Douglas fir dominated stands contain almost no Douglas fir seedlings. This seeming contradiction occurs because Douglas firs are intolerant of deep shade and rarely survive for long within the shaded understory. When a tree dies in a mature forest the canopy opens up and sunlight becomes available as a source of energy for new growth. The shade-tolerant western hemlock seedlings that sprout beneath the canopy have a head-start on other seedlings. This competitive advantage allows the western hemlock to grow rapidly into the sunlight, while other seedlings still struggle to emerge from the soil. The boughs of the growing western hemlock limit the sunlight for smaller trees and severely limit the chances of shade-intolerant trees, such as the Douglas fir. Over the course of centuries, western hemlock typically come to dominate the canopy of an old-growth lowland rainforest.

Douglas firs are seral trees in temperate rainforest, and possess thicker bark and a somewhat faster growth rate than most other climax trees of the area, such as the western hemlock and western redcedar. This quality often gives Douglas firs a competitive advantage when the forest experiences a major disturbance such as fire. Periodically, portions of a Pacific Northwest lowland forest may be burned by wildfire, may be logged, or may be blown down by a wind storm. These types of disturbances allow Douglas fir to regenerate in openings, and low-intensity fires often leave Douglas fir trees standing on drier sites, while less drought- and fire-tolerant species are unable to get established.

Conifers dominate the climax forests of the coast Douglas fir. All of the climax conifers that grow alongside it can live for centuries, with a few species capable of living for over a millennium. Forests that exist on this time scale experience the type of sporadic disturbances that allow mature stands of Douglas fir to establish themselves as a persistent element within a mature old-growth forest. When old growth forests survive in a natural state, they often look like a patchwork quilt of different forest communities. Western hemlock typically dominate oldgrowth rainforests, but contain sections of Douglas firs, redcedar, alder, and even coast redwood forests on their southern extent, near the Oregon and California border, while Sitka spruce increases in frequency with latitude.

The logging practices of the last 200 years created artificial disturbances that caused Douglas firs to thrive. The Douglas fir's useful wood and its quick growth make it the crop of choice for many timber companies, which typically replant a clear-cut area with Douglas fir seedlings. The high-light conditions that exist within a clear-cut also naturally favor the regeneration of Douglas fir. Because of clear-cut logging, almost all the Pacific Northwest forests not strictly set aside for protection are today dominated by Douglas fir, while the normally dominant climax species, such as western hemlock and western redcedar are less common. On drier sites in California, where Douglas fir behaves as a climax species in the absence of fire, the Douglas fir has become somewhat invasive following fire suppression practices of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; it is becoming a dominant species in many oak woodlands, in which it was previously a minor component.[14]

Uses

Douglas fir is one of the world's best timber producers and yields more timber than any other tree in North America. The wood is used for dimensional lumber, timbers, pilings, and plywood. Creosote treated pilings and decking are used in marine structures. The wood is also made into railroad ties, mine timbers, house logs, posts and poles, fencing, flooring, pulp, and furniture. Douglas fir is used extensively in landscaping. It is planted as a specimen tree or in mass screenings. It is also a popular Christmas tree.

This plant has ornamental value in large parks and gardens.[15]

Away from its native area, it is also extensively used in forestry as a plantation tree for timber in Europe, New Zealand, Chile and elsewhere. It is also naturalised throughout Europe,[16] Argentina and Chile (called Pino Oregón), and in New Zealand sometimes to the extent of becoming an invasive species (termed a wilding conifer) subject to control measures.

The buds have been used to flavor eau de vie, a clear, colorless fruit brandy.[17]

Native Hawaiians built waʻ kaulua (double-hulled canoes) from coast Douglas fir logs that had drifted ashore.[18]

Largest trees

- The tallest tree in the United Kingdom is a coast Douglas fir. The tree, growing in Reelig Glen by Inverness is called Dughall Mor and stands at 64 metres (210 ft). It was measured in 2005 by Tony Kirkham and Jon Hammerton from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, the late Jim Paterson from The Tree Register and David Jardine of the Forestry Commission.[19]

- A tree cut down in 1902 at Lynn Valley on the north shore of Vancouver, British Columbia, was reported to have measured 415 feet (126 m) in height, and 14.25 feet (4.34 m) in diameter.[8][20]

- A Douglas fir felled in 1897 at Loop's Ranch in Whatcom County, Washington reportedly measured 465 feet (142 m) in height, 34 feet (10 m) in circumference at the butt, and 220 feet (67 m) to the first branch. With a volume of 96,345 board feet (227.35 m3), this tree was estimated to be 480 years old.[21][22][23][24]

- Research suggests Douglas fir could grow to a maximum height of between 430 to 476 feet (131 to 145 m), at which point water supply would fail.[25][26]

See also

References

- ↑ Farjon, A. (2013). "Pseudotsuga menziesii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2013: e.T42429A2979531. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42429A2979531.en. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ "Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga)". Common Trees of the Pacific Northwest. Oregon State University. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ Dictionary of Upriver Halkomelem, Volume I, pp. 213. Galloway, Brent Douglas.

- ↑ James R. Griffin (September 1964). "A New Douglas-Fir Locality in Southern California". Forest Science: 317–319. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ↑ James R. Griffin; William B. Critchfield (1976). The Distribution of Forest Trees in California USDA Forest Service Research Paper PSW – 82/1972 (PDF). Berkeley, California: USDA Forest Service. p. 114. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- ↑ Carder, A. (1995). Forest Giants of the World: Past and Present. Ontario: Fitzhenry and Whiteside. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-1-55041-090-7.

- ↑ McArdle, Richard E. (1930). The Yield of Douglas Fir in the Pacific Northwest. United States Department of Agriculture. Technical Bulletin No. 201. p. 7. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- 1 2 Carder, Forest Giants pp. 1-10

- ↑ Vaden, M D. "Doerner Fir - Tallest Douglas Fir". Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ "Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii". Gymnosperm Database. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Rushforth, Keith (1986) [1980]. Bäume [Pocket Guide to Trees] (in German) (2nd ed.). Bern: Hallwag AG. ISBN 3-444-70130-6.

- ↑ https://www.arborday.org/trees/treeguide/treedetail.cfm?itemID=836

- ↑ Barton, G.M. (1972). "New C-methylflavanones from Douglas fir". Phytochemistry. 11 (1): 426–429. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)90036-0.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan (2008), Douglas-fir: Pseudotsuga menziesii, globalTwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Strõmberg

- ↑ "Pseudotsuga menziesii". Royal Horticultural Society.

- ↑ "Distribution of Douglas fir". Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh.

- ↑ Asimov, Eric (August 15, 2007). "An Orchard in a Bottle, at 80 Proof". The New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii". The Gymnosperm Database. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

This was the preferred species for Hawaiian war canoes. The Hawaiians, of course, did not log the trees; they had to rely on driftwood.

- ↑ "The Trees That Made Britain". BBC Wales.

- ↑ Parminter, John (January 1996). "A Tale of a Tree" (PDF). British Columbia Forest History Newsletter. Forest History Association of British Columbia. pp. 3–4. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Topics of The Times" (PDF). The New York Times. March 7, 1897. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ Meehans' Monthly: A Magazine of Horticulture, Botany and Kindred Subjects Published by Thomas Meehan & Sons, 1897, p. 24

- ↑ "This Tree Might Reach to China". The Morning Times. Washington, D.C. February 28, 1897. p. 19. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ Judd, Ron (September 4, 2011). "Restless Native: Giant logged long ago but not forgotten". The Seattle Times. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ↑ Kinver, Mark (August 13, 2008). "Water's the limit for tall trees". BBC News.

- ↑ "Douglas-fir: A 350-foot-long Drinking Straw is As Long As It Gets". Oregon State University. August 11, 2008. Archived from the original on October 8, 2008.

Further reading

- Emily K. Brock, Money Trees: The Douglas Fir and American Forestry, 1900–1944. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 2015.

- Uchytil, Ronald J. (1991). "Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii". Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Service (USFS), Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory – via http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- "Pseudotsuga menziesii". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA.

- Calflora Database: Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas fir)

- Conifers.org: Pseudotsuga menziesii

- Arboretum de Villardebelle – cone photos

- Humboldt State University — Photo Tour: Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii — Institute for Redwood Ecology

- EUFORGEN species page on Pseudotsuga menziesii. Information, genetic conservation units and related resources.