Robert Russa Moton Museum

|

Robert Russa Moton High School | |

|

| |

| |

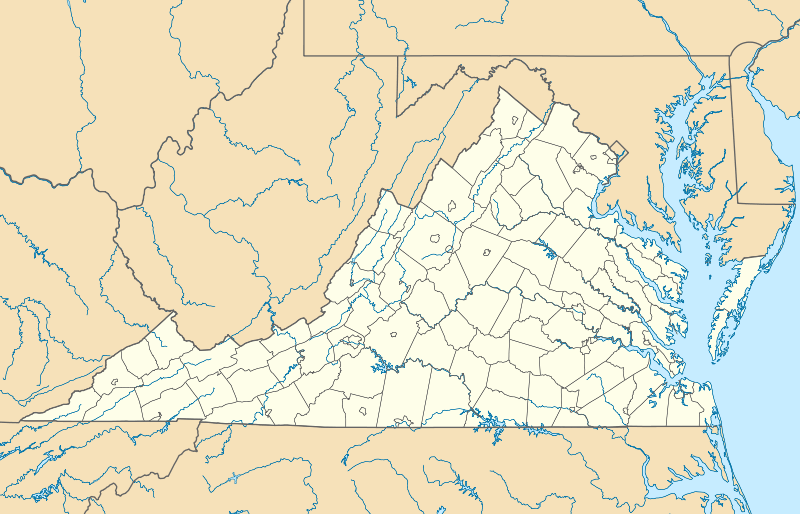

| Location | Jct. of S. Main St. and Griffin Blvd., Farmville, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°17′28″N 78°23′52″W / 37.29111°N 78.39778°WCoordinates: 37°17′28″N 78°23′52″W / 37.29111°N 78.39778°W |

| Area | 5 acres (2.0 ha)[1] |

| Built | 1939 |

| Architect | Unknown |

| Architectural style | Classical Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | 95001177 |

| VLR # | 144-0053 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 24, 1995[2] |

| Designated NHL | August 5, 1998[3] |

| Designated VLR | March 19, 1997[4] |

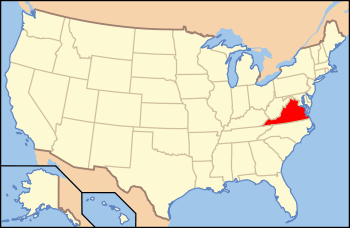

The Robert Russa Moton Museum (popularly known as the "Moton Museum" or "Moton") is a historic site and museum at 900 Griffin Boulevard in Farmville, Prince Edward County, Virginia. It is located in the former Robert Russa Moton High School, considered "the student birthplace of America's Civil Rights Movement" for its role in providing a majority of the plaintiffs in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case desegrating public schools. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1998, and is now a museum dedicated to that history. The museum (and school) were named for African-American educator Robert Russa Moton.

School

The former Moton School is a single-story brick Colonial Revival building, built in 1939 in response to activism and legal challenges from the local African-American community and legal challenges from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It houses six classrooms and an office arranged around a central auditorium. It had no cafeteria or restrooms for teachers. Built to handle 180 students, already by the 1940s it struggled to hold 450; the County, whose all-white board refused to appropriate funds for properly expanding the school facilities, built long temporary buildings to house the overflow. Covered with roofing material, they were called the "tar-paper shacks."[1]

Civil Rights history

In 1951 a group of students, led by 16-year-old Barbara Rose Johns and John Arthur Stokes, staged a walkout in protest of the conditions. The NAACP took up their case after students agreed to seek an integrated school rather than improved conditions at their black school. Howard University-trained attorneys Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill filed suit on May 23, 1951. In Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, a state court rejected the suit, agreeing with defense attorney T. Justin Moore that Virginia was vigorously equalizing black and white schools. The verdict was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and was subsequently incorporated into Brown v. Board of Education, in which the court ruled against the principle of "separate but equal" facilities and mandated the integration of public school systems.[1]

In 1953-54, as part of an argument that it was active in seeking to improve separate but equal conditions, the county built a new high school for African-Americans, and this building became an elementary school.

The struggle to integrate the county's schools was one of the longest in the country. The county eventually refused to fund any public schools rather than integrate, as part of a statewide anti-integration effort known as Massive Resistance, and there were no public schools 1959-64. The Prince Edward School Foundation created a series of private schools to educate the county's white children. These schools were supported by tuition grants from the state and tax credits from the county. Prince Edward Academy was one of the first such schools in Virginia which came to be called segregation academies.

Many families and students emigrated elsewhere or were forced to forgo formal education. Some received schooling with relatives outside of the County or in "training centers" and "grassroots schools" held in African-American churches, businesses and civic halls. Others were sent across the state and country to live with host families recruited by local NAACP leaders, the American Friends Service Committee and the all-black Virginia Teachers Association. In 1963–64, at the urging of local organizers, the Kennedy Administration-supported Prince Edward Free Schools opened in four County schools leased by the Prince Edward Free Schools Association. The 1964 Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County Supreme Court decision ordered the reopening of Prince Edward County Public Schools with full integration.

This building served as a primary school in the county school system until 1993. At the time of the school's final closure, the Martha E. Forrester Council of Women launched a movement to preserve it as a memorial to the struggle for civil rights in education. In 1998, R. R. Moton School was declared a National Historic Landmark.[3]

Museum

Today the Moton School stands as a reminder of the struggle for Civil Rights in Education. A 1994 New York Newsday report commended Prince Edward County as the only area involved in the Brown decision to desegregate its schools successfully and peacefully. The museum houses exhibits containing Moton High School memorabilia, artifacts of the Civil Rights Movement, and oral histories of former teachers and students who recall their experiences of the student walkout and the school closings. Docents are available to give guided tours of the museum. In 2013, Moton completed a $5.5 million renovation and open its first permanent exhibition, The Moton School Story: Children of Courage.

The museum also serves as a Center for the Study of Civil Rights in Education, providing programs to explore the history of desegregation in education and to promote dialogue about community relations. It is also an anchor site of the Civil Rights in Education Heritage Trail. The trail contains 41 sites across southside Virginia which depict the broadening of educational opportunities.

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Virginia

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Prince Edward County, Virginia

References

- 1 2 3 Jarl K. Jackson, Julie L. Vosmik, Tara D. Morrison and Marie Tyler-McGraw (1998). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Robert Russa Moton High School / Farmville Elementary School; VDHR File No. 144-53" (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying 7 photos, exterior and interior, from 1995 (32 KB)

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Robert Russa Moton High School". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

Further reading

- Christopher Bonastia, Southern Stalemate: Five Years Without Public Education in Prince Edward County, Virginia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Bob Smith, They Closed Their Schools. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1963.

External links

- Robert Russa Moton Museum official site

- Robert Russa Moton High School, one photo, at Virginia DHR

- Brown v. Board: Five Communities That Changed America, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Edwilda Gustava Allen Isaac, one of the teenagers involved with the walkout, honored as part of the Virginia Women in History award at the Library of Virginia