Vilnius

| Vilnius | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

|

| |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): Jerusalem of Lithuania, Athens of the North | |||

|

Motto: Unitas, Justitia, Spes (Latin: Unity, Justice, Hope) | |||

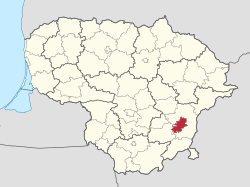

Location of Vilnius | |||

| Coordinates: 54°41′N 25°17′E / 54.683°N 25.283°ECoordinates: 54°41′N 25°17′E / 54.683°N 25.283°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Ethnographic region | Dainava | ||

| County | Vilnius County | ||

| Municipality | Vilnius City Municipality | ||

| Capital of | Lithuania | ||

| First mentioned | 1323 | ||

| Granted city rights | 1387 | ||

| Elderships | |||

| Government | |||

| • Type | City council | ||

| • Mayor | Remigijus Šimašius | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 401 km2 (155 sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 9,731 km2 (3,757 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 112 m (367 ft) | ||

| Population (2015)[1] | |||

| • City | 542,664 | ||

| • Rank | (52nd in EU) | ||

| • Density | 1,392/km2 (3,610/sq mi) | ||

| • Urban | 692,528[2] | ||

| • Metro | 805,142[3] | ||

| • Metro density | 83/km2 (210/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Vilnian | ||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||

| Postal code | 01001-14191 | ||

| Area code(s) | (+370) 5 | ||

| GDP (nominal) Vilnius county[4] | 2015 | ||

| - Total | €15.1 billion/ USD 17 billion | ||

| - Per capita | €18,700/ USD 21,000[5] | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Vilnius (Lithuanian pronunciation: [ˈvʲɪlʲnʲʊs]; Polish: Wilno, see also other names) is the capital of Lithuania and its largest city, with a population of 542,664 as of 2015.[6] Vilnius is located in the southeast part of Lithuania and is the second largest city in the Baltic states. Vilnius is the seat of the main government institutions of Lithuania as well as of the Vilnius District Municipality. Vilnius is classified as a Gamma global city according to GaWC studies, and is known for the architecture in its Old Town, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994. Its Jewish influence until the 20th century has led to it being described as the "Jerusalem of Lithuania" and Napoleon named it "the Jerusalem of the North" as he was passing through in 1812. In 2009, Vilnius was the European Capital of Culture, together with the Austrian city of Linz.

Etymology and other names

The name of the city originates from the Vilnia River.[7] The city has also been known by many derivate spellings in various languages throughout its history: Vilna was common in English. The most notable non-Lithuanian names for the city include: Polish: Wilno, Belarusian: Вiльня, German: Wilna, Latvian: Viļņa, Russian: Вильнюс, Yiddish: ווילנע (Vilne), Czech: Vilnius. An older Russian name was Вильна/Вильно (Vilna/Vilno),[8][9] although Вильнюс (Vilnius) is now used. The names Wilno, Wilna and Vilna have also been used in older English, German, French and Italian language publications when the city was one of the capitals of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and later of Second Polish Republic. The name Vilna is still used in Finnish, Portuguese, Spanish, and Hebrew. Wilna is still used in German, along with Vilnius.

The neighborhoods of Vilnius also have names in other languages, which represent the languages spoken by various ethnic groups in the area.

History

Early history and Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Historian Romas Batūra identifies the city with Voruta, one of the castles of Mindaugas, crowned in 1253 as King of Lithuania. During the reign of Vytenis a city started to emerge from a trading settlement and the first Franciscan Catholic church was built.

The city was first mentioned in written sources in 1323, when the Letters of Grand Duke Gediminas were sent to German cities inviting Germans (including German Jews) to settle in the capital city, as well as to Pope John XXII. These letters contain the first unambiguous reference to Vilnius as the capital; Old Trakai Castle had been the earlier seat of the court of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

According to legend, Gediminas dreamt of an iron wolf howling on a hilltop and consulted a pagan priest for its interpretation. He was told: "What is destined for the ruler and the State of Lithuania, is thus: the Iron Wolf represents a castle and a city which will be established by you on this site. This city will be the capital of the Lithuanian lands and the dwelling of their rulers, and the glory of their deeds shall echo throughout the world".[10] The location offered practical advantages: it lay within the Lithuanian heartland at the confluence of two navigable rivers, surrounded by forests and wetlands that were difficult to penetrate. The duchy had been subject to intrusions by the Teutonic Knights.[11]

Vilnius was the flourishing capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the residence of the Grand Duke. Gediminas expanded the Grand Duchy through warfare along with strategic alliances and marriages. At its height it covered the territory of modern-day Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Transnistria, and portions of modern-day Poland and Russia. His grandchildren Vytautas the Great and Jogaila, however, fought civil wars. During the Lithuanian Civil War of 1389–1392, Vytautas besieged and razed the city in an attempt to wrest control from Jogaila. The two later settled their differences; after a series of treaties culminating in the 1569 Union of Lublin, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was formed. The rulers of this federation held either or both of two titles: Grand Duke of Lithuania or King of Poland. In 1387, Jogaila acting as a Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland Władysław II Jagiełło, granted Magdeburg rights to the city.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The city underwent a period of expansion. The Vilnius city walls were built for protection between 1503 and 1522, comprising nine city gates and three towers, and Sigismund August moved his court there in 1544.

Its growth was due in part to the establishment of Alma Academia et Universitas Vilnensis Societatis Iesu by King Stefan Bathory in 1579. The university soon developed into one of the most important scientific and cultural centres of the region and the most notable scientific centre of the Commonwealth.

During its rapid development, the city was open to migrants from the territories of the Grand Duchy and further. A variety of languages were spoken: Lithuanian, Polish, Ruthenian, Russian, Old Church Slavonic, Latin, German, Yiddish, Hebrew, and Turkic languages; the city was compared to Babylon.[11] Each group made its unique contribution to the life of the city, and crafts, trade, and science prospered.

The 17th century brought a number of setbacks. The Commonwealth was involved in a series of wars, collectively known as The Deluge. During the Russo-Polish War (1654–1667), Vilnius was occupied by Russian forces; it was pillaged and burned, and its population was massacred. During the Great Northern War it was looted by the Swedish army. An outbreak of bubonic plague in 1710 killed about 35,000 residents; devastating fires occurred in 1715, 1737, 1741, 1748, and 1749.[11] The city's growth lost its momentum for many years, but even despite this fact, at the end of the 18th century and before the Napoleon wars, Vilnius, with 56,000 inhabitants, entered the Russian Empire as its 3rd largest city.

In the Russian Empire

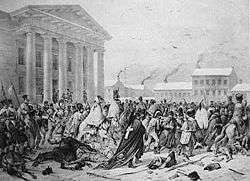

The fortunes of the Commonwealth declined during the 18th century. Three partitions took place, dividing its territory among the Russian Empire, the Habsburg Empire, and the Kingdom of Prussia. After the third partition of April 1795, Vilnius was annexed by the Russian Empire and became the capital of the Vilna Governorate. During Russian rule, the city walls were destroyed, and, by 1805, only the Gate of Dawn remained. In 1812, the city was taken by Napoleon on his push towards Moscow, and again during the disastrous retreat. The Grande Armée was welcomed in Vilnius. Thousands of soldiers died in the city during the eventual retreat; the mass graves were uncovered in 2002.[11] Inhabitants expected Tsar Alexander I to grant them autonomy in response to Napoleon's promises to restore the Commonwealth, but Vilnius didn't become autonomous by itself nor as a part of Congress Poland.

Following the November Uprising in 1831, Vilnius University was closed and Russian repressions halted the further development of the city. Civil unrest in 1861 was suppressed by the Imperial Russian Army.[12]

During the January Uprising in 1863, heavy fighting occurred within the city, but was brutally pacified by Mikhail Muravyov, nicknamed The Hangman by the population because of the number of executions he organized. After the uprising, all civil liberties were withdrawn, and use of the Polish[13] and Lithuanian languages was banned.[14] Vilnius had a vibrant Jewish population: according to Russian census of 1897, out of the total population of 154,500, Jews constituted 64,000 (approximately 40%).[15] During the early 20th century, the Lithuanian-speaking population of Vilnius constituted only a small minority, with Polish, Yiddish, and Russian speakers comprising the majority of the city's population.[16]

In Poland

During World War I, Vilnius and the rest of Lithuania was occupied by the German Army from 1915 until 1918. The Act of Independence of Lithuania, declaring Lithuanian independence from any affiliation to any other nation, was issued in the city on 16 February 1918. After the withdrawal of German forces, the city was briefly controlled by Polish self-defence units, which were driven out by advancing Soviet forces. Vilnius changed hands again during the Polish-Soviet War and the Lithuanian Wars of Independence: it was taken by the Polish Army, only to fall to Soviet forces again. Shortly after its defeat in the battle of Warsaw, the retreating Red Army, in order to delay the Polish advance, ceded the city to Lithuania after signing the Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty on 12 July 1920.[17]

Poland and Lithuania both perceived the city as their own. The League of Nations became involved in the subsequent dispute between the two countries. The League brokered the Suwałki Agreement on 7 October 1920. Although neither Vilnius or the surrounding region was explicitly addressed in the agreement, numerous historians have described the agreement as allotting Vilnius to Lithuania.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26] On 9 October 1920, the Polish Army surreptitiously, under General Lucjan Żeligowski, seized Vilnius during an operation known as Żeligowski's Mutiny. The city and its surroundings were designated as a separate state, called the Republic of Central Lithuania. On 20 February 1922 after the highly contested election in Central Lithuania, the entire area was annexed by Poland, with the city becoming the capital of the Wilno Voivodship (Wilno being the name of Vilnius in Polish). Kaunas then became the temporary capital of Lithuania. Lithuania vigorously contested the Polish annexation of Vilnius, and refused diplomatic relations with Poland. The predominant languages of the city were still Polish and, to a lesser extent, Yiddish. The Lithuanian-speaking population at the time was a small minority, at about 6% of the city's population according even to contemporary Lithuanian sources.[27] The Council of Ambassadors and the international community (with the exception of Lithuania) recognized Polish sovereignty over Vilnus region in 1923.[28]

Vilnius University was reopened in 1919 under the name of Stefan Batory University[29] By 1931, the city had 195,000 inhabitants, making it the fifth largest city in Poland with varied industries, such as Elektrit, a factory that produced radio receivers.

World War II

World War II began with the German invasion of Poland in September 1939. The secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had partitioned Lithuania and Poland into German and Soviet spheres of interest. On 19 September 1939, Vilnius was seized by the Soviet Union (which invaded Poland on 17 September). The USSR and Lithuania concluded a mutual assistance treaty on 10 October 1939, with which the Lithuanian government accepted the presence of Soviet military bases in various parts of the country. On 28 October 1939, the Red Army withdrew from the city to its suburbs (to Naujoji Vilnia) and Vilnius was given over to Lithuania. A Lithuanian Army parade took place on 29 October 1939 through the city centre. The Lithuanians immediately attempted to Lithuanize the city, for example by Lithuanizing Polish schools.[30] However, the whole of Lithuania was annexed by the Soviet Union on 3 August 1940 following a June ultimatum from the Soviets demanding, among other things, that unspecified numbers of Red Army soldiers be allowed to enter the country for the purpose of helping to form a more pro-Soviet government. After the ultimatum was issued and Lithuania further occupied, a Soviet government was installed with Vilnius as the capital of the newly created Lithuanian SSR. Between 20,000 and 30,000 of the city's inhabitants were subsequently arrested by the NKVD and sent to gulags in the far eastern areas of the Soviet Union.[31] The Soviets devastated city industries, moving the major Polish radio factory Elektrit, along with a part of its labour force, to Minsk in Belarus, where it was renamed the Vyacheslav Molotov Radio Factory, after Stalin's Minister of Foreign Affairs.

On 22 June 1941, the Germans launched Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union. Vilnius was captured on 24 June.[32] Two ghettos were set up in the old town centre for the large Jewish population – the smaller one of which was "liquidated" by October.[33] The larger ghetto lasted until 1943, though its population was regularly deported in roundups known as "Aktionen".[34] A failed ghetto uprising on 1 September 1943 organized by the Fareinigte Partizaner Organizacje (the United Partisan Organization, the first Jewish partisan unit in German-occupied Europe),[35] was followed by the final destruction of the ghetto. During the Holocaust, about 95% of the 265,000-strong Jewish population of Lithuania was murdered by the German units and Lithuanian Nazi collaborators, many of them in Paneriai, about 10 km (6.2 mi) west of the old town centre (see the Ponary massacre). In 2015, a street sign was unveiled in Kūdrų street for Righteous Among the Nations Ona Šimaitė, along with that street being renamed after her.[36]

Lithuanian SSR – in Soviet Union

In July 1944, Vilnius was taken from the Germans by the Soviet Army and the Polish Armia Krajowa (see Operation Ostra Brama and the Vilnius Offensive).[37] The NKVD arrested the leaders of the Armia Krajowa after requesting a meeting. Shortly afterwards, the town was once again incorporated into the Soviet Union as the capital of the Lithuanian SSR.

The war had irreversibly altered the town – most of the predominantly Polish and Jewish population had been expelled and exterminated respectively, during and after the German occupation. Some members of the intelligentsia and former Waffen SS members hiding in the forest were now targeted and deported to Siberia after the war. The majority of the remaining population was compelled to relocate to Communist Poland by 1946, and Sovietization began in earnest. Only in the 1960s did Vilnius begin to grow again, following an influx of Lithuanians and Poles from neighbouring regions as well as from other areas of the Soviet Union (particularly Russia and Belarus). Microdistricts were built in the elderates of Šeškinė, Žirmūnai, Justiniškės and Fabijoniškės.

Independent Lithuania

On 11 March 1990, the Supreme Council of the Lithuanian SSR announced its secession from the Soviet Union and intention to restore an independent Republic of Lithuania.[38] As a result of these declarations, on 9 January 1991, the Soviet Union sent in troops. This culminated in the 13 January attack on the State Radio and Television Building and the Vilnius TV Tower, killing at least fourteen civilians and seriously injuring 700 more. The Soviet Union finally recognised Lithuanian independence in September 1991. The current Constitution, as did the earlier Lithuanian Constitution of 1922, mentions that "…the capital of the State of Lithuania shall be the city of Vilnius, the long-standing historical capital of Lithuania".

Vilnius has been rapidly transformed, and the town has emerged as a modern European city. Many of its older buildings have been renovated, and a business and commercial area is being developed into the New City Centre, expected to become the city's main administrative and business district on the north side of the Neris river. This area includes modern residential and retail space, with the municipality building and the 129-metre (423') Europa Tower as its most prominent buildings. The construction of Swedbank's headquarters is symbolic of the importance of Scandinavian banks in Vilnius. The building complex "Vilnius Business Harbour" was built in 2008, and one of its towers is now the 5th tallest building in Lithuania. More buildings are scheduled for construction in the area. Vilnius was selected as a 2009 European Capital of Culture, along with Linz, the capital of Upper Austria. Its 2009 New Year's Eve celebration, marking the event, featured a light show said to be "visible from outer space".[39] In preparation, the historical centre of the city was restored, and its main monuments were renovated.[40] The global economic crisis led to a drop in tourism which prevented many of the projects from reaching their planned extent, and allegations of corruption and incompetence were made against the organisers,[41][42] while tax increases for cultural activity led to public protests[43] and the general economic conditions sparked riots.[44] Today, Vilnius' population and economy are rapidly growing. In 2015 Remigijus Šimašius became the first directly elected mayor of the city.[45]

Vilnius has some of the highest internet speeds in the world,[46][47] with an average download speed of 36.37 MB/s and upload speed of 28.51 MB/s.

Vilnius has access to groundwater, and there is no need to use extensive chemicals in treating surface water from lakes or rivers, providing residents with some of the cleanest and healthiest tap water access in Europe.[48][49]

On 28–29 November 2013, Vilnius hosted the Eastern Partnership Summit in the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania. Many European presidents, prime ministers and other high-ranking officials participated in the event.[50] On 29 November 2013, Georgia and Moldova signed association and free trade agreements with the European Union.[51] Previously, Ukraine and Armenia were also expected to sign the agreements but postponed the decision, sparking large protests in the former country.

On 20 December 2013, CNN named Vilnius Cathedral Square's Christmas tree as the best in the world,[52] while EssentialTravel.co.uk mentioned Vilnius as one of the ten best destinations to spend your Christmas.[53]

Geography

.jpg)

Vilnius is situated in south-eastern Lithuania (54°41′N 25°17′E / 54.683°N 25.283°E) at the confluence of the Vilnia and Neris Rivers. Lying close to Vilnius is a site some claim to be the Geographical Centre of Europe.

Vilnius lies 312 km (194 mi) from the Baltic Sea and Klaipėda, the chief Lithuanian seaport. Vilnius is connected by highways to other major Lithuanian cities, such as Kaunas (102 km or 63 mi away), Šiauliai (214 km or 133 mi away) and Panevėžys (135 km or 84 mi away). The city's off-centre location can be attributed to the changing shape of the nation's borders through the centuries; Vilnius was once not only culturally but also geographically at the centre of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The current area of Vilnius is 402 square kilometres (155 sq mi). Buildings occupy 29.1% of the city; green spaces occupy 68.8%; and waters occupy 2.1%.[54]

Climate

The climate of Vilnius is humid continental (Köppen climate classification Dfb).[55] Temperature records have been kept since 1777.[56] The average annual temperature is 6.1 °C (43 °F); in January the average temperature is −4.9 °C (23 °F), in July it is 17.0 °C (63 °F). The average precipitation is about 661 millimetres (26.02 in) per year. Average annual temperatures in the city have increased significantly during the last 30 years, a change which the Lithuanian Hydrometeorological Service attributes to global warming induced by human activities.[57]

Summer days are pleasantly warm and sometimes hot, especially in July and August, with temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F) throughout the day during periodic heat waves. Night-life in Vilnius is in full swing at this time of year, and outdoor bars, restaurants and cafés become very popular during the daytime.

Winters can be very cold, with temperatures rarely reaching above freezing – temperatures below −25 °C (−13 °F) are not unheard-of in January and February. Vilnius's rivers freeze over in particularly cold winters, and the lakes surrounding the city are almost always permanently frozen during this time of year. A popular pastime is ice-fishing.

| Climate data for Vilnius | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

31.8 (89.2) |

33.4 (92.1) |

35.4 (95.7) |

34.4 (93.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

35.4 (95.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −3.5 (25.7) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

21.1 (70) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.6 (70.9) |

16.4 (61.5) |

10.2 (50.4) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.1 (21) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

5.7 (42.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

6.02 (42.83) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −8.7 (16.3) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

1.6 (34.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.3 (54.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

2.4 (36.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −37.2 (−35) |

−35.8 (−32.4) |

−29.6 (−21.3) |

−14.1 (6.6) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.0 (32) |

3.5 (38.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−22.5 (−8.5) |

−30.5 (−22.9) |

−37.2 (−35) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38.9 (1.531) |

34.4 (1.354) |

37.0 (1.457) |

46.2 (1.819) |

52.1 (2.051) |

72.7 (2.862) |

79.3 (3.122) |

75.8 (2.984) |

65.2 (2.567) |

51.5 (2.028) |

51.5 (2.028) |

49.2 (1.937) |

653.5 (25.728) |

| Average precipitation days | 21.7 | 18.4 | 17.5 | 10.2 | 12.4 | 11.7 | 11.4 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 13.5 | 16.7 | 21.2 | 174.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87.2 | 84.3 | 77.6 | 65.5 | 67.2 | 70.2 | 73.3 | 74.1 | 78.5 | 84.7 | 90.0 | 89.0 | 78.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 36 | 71 | 117 | 164 | 241 | 231 | 219 | 217 | 140 | 94 | 33 | 25 | 1,588 |

| Source #1: World Meteorological Organization (avg high and low)[58] NOAA (sun and extremes)[59] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Weatherbase (precipitation and humidity)[60] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Lithuanians | Poles | Russians | Jews | Others | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1897[61] | 3,131 | 2% | 47,795 | 30.1% | 30,967 | 20% | 61,847 | 40% | 10,792 | 7% | 154,532 |

| 1931[62] | 1,579 | 0.8% | 128,600 | 65.5% | 7,400 | 3.8% | 54,600 | 27.8% | 4,166 | 2.1% | 196,345 |

| 1959[63] | 79,400 | 34% | 47,200 | 20% | 69,400 | 29% | 16,400 | 7% | 23,700 | 10% | 236,100 |

| 2001[64] | 318,510 | 57.5% | 104,446 | 18.9% | 77,698 | 14.1% | 2,770 | 0.5% | 50,480 | 9.1% | 553,904 |

| 2012[65] | 337,000 | 63.2% | 88,380 | 16.5% | 64,275 | 12% | N/A | 45,976 | 8.6% | 535,631 | |

- 1897: According to the first census in the Russian Empire, in 1897 population of Vilnius was 154,500. The majority of Vilnius population at the time was made up by Jews (61,847) and Poles (47,795). Other groups included Russians (30,967), Belarusians (6,514) and Ukrainians (517), Lithuanians (3,131), Germans (2,170), Tartars (722) and Latvians (184).[66]

- 1916: According to the census of 14 December 1916 by the occupying German forces at the time, there were a total of 138,794 inhabitants in Vilnius. This number was made up of the following nationalities: Poles 53.67% (74,466 inhabitants), Jews 41.45% (57,516 inhabitants), Lithuanians 2.09% (2,909 inhabitants), Russians 1.59% (2,219 inhabitants), Germans 0.63% (880 inhabitants), Belarusians 0.44% (644 inhabitants) and others at 0.13% (193 inhabitants).

- 1923: 167,545 inhabitants, including 100,830 Poles and 55,437 Jews.[62]

- 1931: 196,345 inhabitants.[62] A census of 9 December 1931 reveals that Poles made up 65.9% of the total Vilnius population (128,600 inhabitants), Jews 28% (54,600 inhabitants), Russians 3.8% (7,400 inhabitants), Belarusians 0.9% (1,700 inhabitants), Lithuanians 0.8% (1,579 inhabitants), Germans 0.3% (600 inhabitants), Ukrainians 0.1% (200 inhabitants), others 0.2% (approx. 400 inhabitants). (The Wilno Voivodeship in the same year had 1,272,851 inhabitants, of which 511,741 used Polish as their language of communication; many Belarusians lived there.[67])

- 1959: According to the Soviet census, Vilnius had 236,100 inhabitants, of which 34% (79,400) identified themselves as Lithuanian, 29% (69,400) as Russian, 20% (47,200) as Polish, 7% (16,400) as Jewish and 6% (14,700) as Belarusian.[63]

- 1989: According to the Soviet census, Vilnius had 576,700 inhabitants, of which 50.5% (291,500) were Lithuanian, 20% Russian, 19% Polish and 5% Belarusian.[63]

- 2001: According to the 2001 census by the Vilnius Regional Statistical Office, there were 542,287 inhabitants in the Vilnius City Municipality, of which 57.8% were Lithuanians, 18.7% Poles, 14% Russians, 4.0% Belarusians, 1.3% Ukrainians and 0.5% Jews; the remainder indicated other nationalities or refused to answer.

- 2011: According to the 2011 census by Statistics Lithuania, Vilnius is inhabited by people of 128 different ethnicities which makes it the most ethnically diverse city in Lithuania, while the majority of Vilnius population is made up by Lithuanians (63.6%).[68]

Evolution

Demographic evolution of Vilnius between 1796 and 2015:

| Historical population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: [69] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Culture

Vilnius is a cosmopolitan city with diverse architecture. There are 65 churches in Vilnius. Like most medieval towns, Vilnius was developed around its Town Hall. The main artery, Pilies Street, links the Royal Palace with Town Hall. Other streets meander through the palaces of feudal lords and landlords, churches, shops and craftsmen's workrooms. Narrow, curved streets and intimate courtyards developed in the radial layout of medieval Vilnius. Vilnius Old Town, the historical centre of Vilnius, is one of the largest in Europe, at 3.6 km2 (1.4 sq mi). The most valuable historic and cultural sites are concentrated here. The buildings in the old town – there are nearly 1,500 – were built over several centuries, creating a blend of many different architectural styles. Although Vilnius is known as a Baroque city, there are examples of Gothic (e.g. St Anne's Church), Renaissance, and other styles. Their combination is also a gateway to the historic centre of the capital. Owing to its uniqueness, the Old Town of Vilnius was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1994. In 1995, the world's first bronze cast of Frank Zappa[70] was installed in the Naujamiestis district with the permission of the government. The Frank Zappa sculpture confirmed the newly found freedom of expression, and marked the beginning of a new era for Lithuanian society.

The Vilnius Castle Complex, a group of defensive, cultural, and religious buildings that includes Gediminas Tower, Cathedral Square, the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, and the remains of several medieval castles, is part of the National Museum of Lithuania. Lithuania's largest art collection is housed in the Lithuanian Art Museum. The House of the Signatories, where the 1918 Act of Independence of Lithuania was signed, is now a historic landmark. The Museum of Genocide Victims is dedicated to the victims of the Soviet era. On the other side of the Neris, the National Art Gallery holds a permanent exhibition on Lithuanian 20th-century art, as well as numerous exhibitions on modern art.

The Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania, named for the author of the first book printed in the Lithuanian language, holds 6,912,266 physical items. The biggest book fair in Baltic States is annually held in Vilnius at LITEXPO, the Baltic's biggest exhibition centre.[71]

On 10 November 2007, the Jonas Mekas Visual Arts Center was opened by avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas. Its premiere exhibition was entitled The Avant-Garde: From Futurism to Fluxus. There are plans to build the Guggenheim-Hermitage museum, designed by Zaha Hadid. The museum would host exhibitions featuring works from Saint Petersburg's Hermitage Museum and the Guggenheim Museums, along with non-commercial avant-garde cinema, a library, a museum of Lithuanian Jewish culture, and collections of works by Jonas Mekas and Jurgis Mačiūnas.

The Užupis district near the Old Town, which used to be one of the most run down districts of Vilnius during the Soviet Union, is home to a movement of bohemian artists, who operate numerous art galleries and workshops. Užupis declared itself an independent republic on April Fool's Day 1997. In the main square, the statue of an angel blowing a trumpet stands as a symbol of artistic freedom.

Economy

Vilnius is the major economic centre of Lithuania and one of the largest financial centres of the Baltic states. Even though it is home to only 20% of Lithuania's population, it generates about one third of Lithuania's GDP.[72] GDP per capita (nominal) in Vilnius county was $21,000[73] in 2015, making it the wealthiest region in Lithuania. The budget of Vilnius is about €0.5($0.6) billion in 2016.[74] Vilnius contributed almost €3 billion to the national budget in 2008, making up about 40% of the budget. The average annual brutto salary in Vilnius city municipality was about €10,200/$11,300 as of 2015.[75]

Currently in Vilnius there are growing local advanced solar and laser technologies manufacturers centres (such as photovoltaic elements and renewable energy producers:Arginta, Precizika, Baltic Solar, high performance lasers manufacturers: Ekspla, Eksma, biotechnological manufacturers (Fermentas Thermo Fisher, Sicor Biotech), which successfully supply their products into global markets. In 2009, the Barclays Technology Centre was established in Vilnius, which is one of the bank's four global strategic engineering centres.

Education

The city has many universities. The largest and oldest is Vilnius University with 23,000 students. Its main premises are located in the Old Town. The university has a recognised high standard of education, participating in projects with UNESCO and NATO, among others. The University features many Masters programs in English, as well as programs delivered in cooperation with universities all over Europe. The university is currently divided into 14 faculties, 5 institutes, and 4 study and research centres.

Other major universities include Mykolas Romeris University (19,000 students), Vilnius Gediminas Technical University (13,500 students), and Vilnius Pedagogical University (12,500 students). Specialized higher schools with university status include General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania and Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre. The museum associated with the Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts holds about 12,000 artworks.

The National M. K. Čiurlionis School of Art, European Humanities University, Vilnius Academy of Business Law, Vilnius University International Business School, and ISM University of Management and Economics offer post-secondary degrees in several areas.

Religion

| Religion | People | % |

|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic | 350,797 | 65.49% |

| Eastern Orthodox | 47,827 | 8.93% |

| Old Believers | 5,593 | 1.04% |

| Evangelical Lutheran | 1,594 | 0.30% |

| Evangelical Reformed | 1,186 | 0.22% |

| Sunni Muslim | 798 | 0.15% |

| Jewish | 796 | 0.15% |

| Greek Catholic | 167 | 0.03% |

| Karaim | 139 | 0.03% |

| Other | 5,050 | 0.94% |

| None | 47,655 | 8.90% |

| No response | 74,029 | 13.82% |

.jpg)

Vilnius is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vilnius, with the main church institutions and Archdiocesan Cathedral (Vilnius Cathedral) located here. The city of Vilnius became the birthplace of the Divine Mercy Devotion when Saint Faustina began her mission under the guidance and discernment of her new spiritual director Fr. Michał Sopoćko. In 1934 the first Divine Mercy painting was painted by Eugene Kazimierowski under the supervision of Faustina and it presently hangs in the Divine Mercy Sanctuary in Vilnius. There are a number of other active Roman Catholic churches in the city, along with small enclosed monasteries and religion schools. Church architecture includes Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and Neoclassical styles, with important examples of each found in the Old Town. Additionally, Eastern Rite Catholicism has maintained a presence in Vilnius since the Union of Brest. The Baroque Basilian Gate is part of an Eastern Rite monastery.

Once widely known as Yerushalayim De Lita (the "Jerusalem of Lithuania"), Vilnius since the 18th century, was a world centre for the study of the Torah, and had a large Jewish population. A major scholar of Judaism and Kabbalah centred in Vilnius was the famous Rabbi Eliyahu Kremer, also known as the Vilna Gaon. His students have significant influence among Orthodox Jews in Israel and around the globe. Jewish life in Vilnius was destroyed during the Holocaust; there is a memorial stone dedicated to victims of Nazi genocide located in the centre of the former Jewish Ghetto — now Mėsinių Street. The Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum is dedicated to the history of Lithuanian Jewish life. The exact location of Vilnius' largest synagogue, built in the early 1630s and wrecked by Nazi Germany during its occupation of Lithuania, was pinpointed by ground-penetrating radar in June 2015, with excavations set to begin in 2016.[77]

The Karaim are a Jewish sect who migrated to Lithuania from the Crimea to serve as a military elite unit in the 14th century. Although their numbers are very small, the Karaim are becoming more prominent since Lithuanian independence, and have restored their kenesa.[78]

Vilnius has been home to an Eastern Orthodox Christian presence since the 13th or even the 12th century. A famous Russian Orthodox Monastery of the Holy Spirit, is located near the Gate of Dawn. St. Paraskeva's Orthodox Church in the Old Town is the site of the baptism of Hannibal, the great-grandfather of Pushkin, by Tsar Peter the Great in 1705. Many Old Believers, who split from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1667, settled in Lithuania. The Church of St. Michael and St. Constantine was built in 1913. Today a Supreme Council of the Old Believers is based in Vilnius.

A number of Protestant and other Christian groups[79] are represented in Vilnius, most notably the Lutheran Evangelicals and the Baptists.

The pre-Christian religion of Lithuania, centred on the forces of nature as personified by deities such as Perkūnas (the Thunder God), is experiencing some increased interest. Romuva established a Vilnius branch in 1991.[80]

Parks, squares and cemeteries

Almost half of Vilnius is covered by green areas, such as parks, public gardens, natural reserves. Additionally, Vilnius is host to numerous lakes, where residents and visitors swim and have barbecues in the summer. Thirty lakes and 16 rivers cover 2.1% of Vilnius' area, with some of them having sand beaches.

Vingis Park, the city's largest, hosted several major rallies during Lithuania's drive towards independence in the 1980s. Concerts, festivals, and exhibitions are held at Sereikiškės Park, near Gediminas Tower. Sections of the annual Vilnius Marathon pass along the public walkways on the banks of the Neris River. The green area next to the White Bridge is another popular area to enjoy good weather, and has become venue for several music and large screen events.

Cathedral Square in Old Town is surrounded by a number of the city's most historically significant sites. Lukiškės Square is the largest, bordered by several governmental buildings: the Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Finance, the Polish Embassy, and the Genocide Victims' Museum, where the KGB tortured and murdered numerous opposers of the communist regime. An oversized statue of Lenin in its centre was removed in 1991. Town Hall Square has long been a centre of trade fairs, celebrations, and events in Vilnius, including the Kaziukas Fair. The city Christmas tree is decorated there. State ceremonies are often held in Daukantas Square, facing the Presidential Palace.

Rasos Cemetery, consecrated in 1801, is the burial site of Jonas Basanavičius and other signatories of the 1918 Act of Independence, along with the heart of Polish leader Józef Piłsudski. Two of the three Jewish cemeteries in Vilnius were destroyed during the Soviet era; the remains of the Vilna Gaon were moved to the remaining one. A monument was erected at the place where Užupis Old Jewish Cemetery was.[81] On 23 October 2011, a swastika has been sprayed on the monument, as what seems to be an anti-Semitic act.[82] About 18,000 burials have been made in the Bernardine Cemetery, established in 1810; it was closed during the 1970s and is now being restored. Antakalnis Cemetery, established in 1809, contains various memorials to Polish, Lithuanian, German and Russian soldiers, along with the graves of those who were killed during the January Events.

On 20 October 2013, Bernardinai garden, previously known as Sereikiškės Park, was opened after reconstruction. The authentic 19th-century Vladislovas Štrausas environment was restored.[83]

Sport

Several teams are based in the city. The largest is the basketball club BC Lietuvos Rytas, which participates in European competitions such as the Euroleague and Eurocup, the domestic Lithuanian Basketball League, winning the ULEB Cup (predecessor to the Eurocup) in 2005 and the Eurocup in 2009. Its home arena is the 2,500-seat Lietuvos Rytas Arena; all European matches and important domestic matches are played in the 11,000-seat Siemens Arena.

Vilnius also has several football teams. FK Žalgiris is the main football team. The club plays at LFF Stadium in Vilnius (capacity 5,067).[84]

Olympic champions in swimming Lina Kačiušytė and Robertas Žulpa are from Vilnius. There are several public swimming pools in Vilnius with Lazdynai Swimming Pool being the only Olympic-size swimming pool of the city.[85]

The city is home to the Lithuanian Bandy Association,[86] Badminton Federation,[87] Canoeing Sports Federation,[88] Baseball Association,[89] Biathlon Federation,[90] Sailors Union,[91] Football Federation,[92] Fencing Federation,[93] Cycling Sports Federation,[94] Archery Federation,[95] Athletics Federation,[96] Ice Hockey Federation,[97] Basketball Federation,[98] Curling Federation,[99] Rowing Federation,[100] Wrestling Federation,[101] Speed Skating Association,[102] Gymnastics Federation,[103] Equestrian Union,[104] Modern Pentathlon Federation,[105] Shooting Union,[106] Triathlon Federation,[107] Volleyball Federation,[108] Tennis Union,[109] Taekwondo Federation,[110] Weightlifting Federation,[111] Table Tennis Association,[112] Skiing Association,[113] Rugby Federation,[114] Swimming Federation.[115]

Transport

Navigability of the river Neris is very limited and no regular water routes exist, although it was used for navigation in the past.[116] The river rises in Belarus, connecting Vilnius and Kernavė, and becomes a tributary of Nemunas river in Kaunas.

Vilnius Airport serves most Lithuanian international flights to many major European destinations. Currently, the airport has 89 destinations in 28 different countries. The airport is situated only 5 km (3.1 mi) away from the centre of the city, and has a direct rail link to Vilnius railway station.

The Vilnius railway station is an important hub serving direct passenger connections to Minsk, Kaliningrad, Moscow and Saint Petersburg as well as being a transit point of Pan-European Corridor IX.

Vilnius is the starting point of the Vilnius–Kaunas–Klaipėda motorway that runs across Lithuania and connects the three major cities as well as it is the part of European route E85. The Vilnius–Panevėžys motorway is a branch of the Via Baltica.

Public transport

.jpg)

Vilnius has a well-developed public transportation system; 45% of the population take public transport to work, one of the highest figures in all of Europe.[117] The bus network and the trolleybus network are run by Vilniaus viešasis transportas. There are over 60 bus and 22 trolleybus routes, the trolleybus network is one of the most extensive in Europe. Over 250 buses and 260 trolleybuses transport about 500,000 passengers every workday. Students, elderly, and the disabled receive large discounts (up to 80%) on the tickets. The first regular bus routes were established in 1926, and the first trolleybuses were introduced in 1956.

At the end of 2007, a new electronic monthly ticket system was introduced. It was possible to buy an electronic card in shops and newspaper stands and have it credited with an appropriate amount of money. The monthly e-ticket cards could be bought once and credited with an appropriate amount of money in various ways including the Internet. Previous paper monthly tickets were in use until August 2008.[118]

The ticket system changed again from 15 August 2012. E-Cards were replaced by Vilnius Citizen Cards ("Vilniečio Kortelė"). It is now possible to buy a card or change an old one in newspaper stands and have it credited with an appropriate amount of money or a particular type of ticket. Single trip tickets have been replaced by 30 and 60-minute tickets.

The public transportation system is dominated by the low-floor Volvo and Mercedes-Benz buses as well as Solaris trolleybuses. There are also plenty of the traditional Skoda vehicles, built in the Czech Republic, still in service, and many of these have been extensively refurbished internally. This is a result of major improvements that started in 2003 when the first brand-new Mercedes-Benz buses were bought. In 2004, a contract was signed with Volvo Buses to buy 90 brand-new 7700 buses over the following three years.

An electric tram and a metro system through the city were proposed in the 2000s. However, neither has progressed beyond initial planning.[119]

Governance

Municipal Council

Vilnius City Municipality is one of 60 municipalities of Lithuania and includes the nearby town of Grigiškės, three villages, and some rural areas. The town of Grigiškės was separated from the Trakai District Municipality and attached to the Vilnius City Municipality in 2000.

A 51-member council is elected to four-year terms; the candidates are nominated by registered political parties. As of the 2011 elections, independent candidates also were permitted. The last election was held in March 2015, terms are 4 years. The results are:

- Liberal Movement – 15 seats

- The coalition of the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania and Lithuanian Russian Union – 10

- Homeland Union – Lithuanian Christian Democrats – 8

- Lithuanian Freedom Union (Liberals) – 6

- Social Democratic Party of Lithuania – 4

- List of Lithuania – 4

- Order and Justice – 3

Mayors

Before 2015, mayors were appointed by the council. Starting with the elections in 2015, the mayors are elected directly by the residents. Remigijus Šimašius became the first directly elected mayor of the city.

- 1990 – Arūnas Grumadas (the president of council)

- 1993 – Valentinas Šapalas (the president of council)

- 1995 – Alis Vidūnas

- 1997 – Rolandas Paksas

- 1999 – Juozas Imbrasas

- 2000 – Rolandas Paksas (2nd time)

- 2001 – Artūras Zuokas

- 2003 – Gediminas Paviržis

- 2003 – Artūras Zuokas (2nd time)

- 2007 – Juozas Imbrasas (2nd time)

- 2009 – Vilius Navickas

- 2010 – Raimundas Alekna

- 2011 – Artūras Zuokas (3rd time)

- 2015 – Remigijus Šimašius

Subdivisions

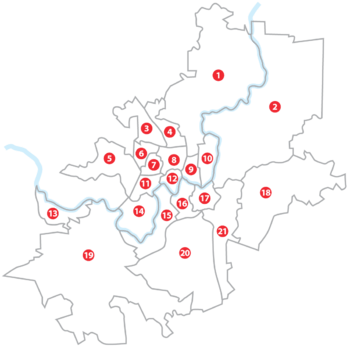

Elderships, a statewide administrative division, function as municipal districts. The 21 elderships are based on neighbourhoods:

- Verkiai — includes Baltupiai, Jeruzalė, Santariškės, Balsiai, Visoriai

- Antakalnis — includes Valakampiai, Turniškės, Dvarčionys

- Pašilaičiai — includes Tarandė

- Fabijoniškės — includes Bajorai

- Pilaitė

- Justiniškės

- Viršuliškės

- Šeškinė

- Šnipiškės

- Žirmūnai — includes Šiaurės miestelis

- Karoliniškės

- Žvėrynas

- Grigiškės — a separate town

- Lazdynai

- Vilkpėdė — includes Vingis Park

- Naujamiestis — includes bus and train stations

- Senamiestis (Old Town) — includes Užupis

- Naujoji Vilnia — includes Pavilnys, Pūčkoriai

- Paneriai — includes Trakų Vokė, Gariūnai

- Naujininkai — includes Kirtimai, Salininkai, Vilnius International Airport

- Rasos — includes Belmontas, Markučiai

Twin towns – Sister cities

|

Significant depictions in popular culture

- Vilnius is mentioned in the movie The Hunt For Red October (1990) as being the boyhood home of the sub commander Marko Ramius, and as being where his grandfather taught him to fish; he is also referenced once in the movie as "The Vilnius Schoolmaster". Ramius is played by Sean Connery.

- Author Thomas Harris' character Hannibal Lecter is revealed to be from Vilnius and its aristocracy in the movie Hannibal Rising. Lecter is portrayed more popularly and often by Sir Anthony Hopkins, although Brian Cox played Lecter in the movie Manhunter.

- The memoir, A Partisan from Vilna (2010),[134] details the life and struggles of Rachel Margolis. Her family's sole survivor, she escaped from the Vilna Ghetto with other members of the resistance movement, the FPO (United Partisan Organization), and joined the Soviet partisans in the Lithuanian forests to sabotage the Nazis.

- Vilnius is classified as a city-state in the turn-based strategy game Civilization V.

See also

- Archdiocese of Vilnius

- Coat of arms of Vilnius

- List of monuments in Vilnius

- List of Vilnians

- List of Vilnius Elderships in other languages

- Neighborhoods of Vilnius

- Vilna Ghetto

Footnotes and references

- ↑ osp.stat.gov.lt

- ↑ http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=urb_lpop1&lang=en

- ↑ http://osp.stat.gov.lt/en/populiariausia;jsessionid=729AC568DEC52C227713D3D8CE98BEBB?p_p_id=148_INSTANCE_TSlXL3Yys4Ip&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-2&p_p_col_pos=8&p_p_col_count=10&p_r_p_564233524_resetCur=true&p_r_p_564233524_tag=gyventojai

- ↑ http://osp.stat.gov.lt/en/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?id=8446&status=A

- ↑ http://www.ukforex.co.uk/forex-tools/historical-rate-tools/yearly-average-rates average EUR/ USD ex. rate in 2015

- ↑ http://osp.stat.gov.lt. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Portrait of the Regions of Lithuania – Vilnius city municipality". Department of Statistics. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ Лавринец, Павел (20 October 2004). Русская Вильна: идея и формула. Балканская Русистика (in Russian). Вильнюс. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ↑ Васютинский, А.М.; Дживелегов, А.К.; Мельгунов, С.П. (1912). "Фон Зукков, По дороге в Вильно". Французы в России. 1812 г. По воспоминаниям современников-иностранцев. (in Russian). 1–3. Москва: "Задруга". Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ↑ "Vilnius legend". Municipality of Vilnius.

- 1 2 3 4 Laimonas Briedis (2008). Vilnius: City of Strangers. Baltos Lankos. ISBN 978-9955-23-160-8.

- ↑ Piotr S. Wandycz, The lands of partitioned Poland, 1795–1918, University of Washington Press, 1974, p. 166.

- ↑ Egidijus Aleksandravičius, Antanas Kulakauskas; Carų valdžioje: Lietuva XIX amžiuje ("Lithuania under the reign of Czars in 19th century"); Baltos lankos, Vilnius 1996. Polish translation: Pod władzą carów: Litwa w XIX wieku, Universitas, Kraków 2003, page 90, ISBN 83-7052-543-1

- ↑ Dirk Hoerder, Inge Blank, Horst Rössler, "Roots of the transplanted", East European Monographs, 1994, pg. 69

- ↑ Joshua D. Zimmerman, Poles, Jews, and the politics of nationality, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2004, ISBN 0-299-19464-7, Google Print, p. 16

- ↑ "A 1909 official count of the city found 205,250 inhabitants, of whom 1.2 percent were Lithuanian; 20.7 percent Russian; 37.8 percent Polish; and 36.8 percent Jewish. — Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus 1569–1999. Yale University Press 2003, p. 306.

- ↑ Łossowski, Piotr (1995). Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918–1920 (in Polish). Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza. pp. 126–128. ISBN 83-05-12769-9.

- ↑ Rawi Abdelal (2001). National Purpose in the World Economy: Post-Soviet States in Comparative Perspective. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8977-8.

At the same time, Poland acceded to Lithuanian authority over Vilnius in the 1920 Suwałki Agreement.

- ↑ Glanville Price (1998). Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8014-8977-8.

In 1920, Poland annexed a third of Lithuania's territory (including the capital, Vilnius) in a breach of the Treaty of Suvalkai of 7 October 1920, and it was only in 1939 that Lithuania regained Vilnius and about a quarter of the territory previously occupied by Poland.

- ↑ Smith, David James; Pabriks, Artis; Purs, Aldis; Lane, Thomas (2002). The Baltic States. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-28580-3.

Fighting continued until the agreement at Suwałki between Lithuania and Poland on 7 October 1920, which drew a line of demarcation which was incomplete but indicated that the Vilnius area would be part of Lithuania

- ↑ Eudin, Xenia Joukoff; Fisher, Harold H.; Jones, Rosemary Brown (1957). Soviet Russia and the West, 1920–1927. Stanford University. ISBN 978-0-8047-0478-6.

The League effected an armistice, signed at Suwałki, 7 October 1920, by the terms of which the city was to remain under Lithuanian jurisdiction.

- ↑ Eidintas, Alfonsas; Tuskenis, Edvardas; Zalys, Vytautas (1999). Lithuania in European Politics. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-22458-5.

The Lithuanians and the Poles signed an agreement at Suwałki on 7 October. Both sides were to cease hostilities and to peacefully settle all disputes. The demarcation line was extended only in the southern part of the front, to Bastunai. Vilnius was thus left on the Lithuanian side, but its security was not guaranteed.

- ↑ Hirsz Abramowicz; Dobkin, Eva Zeitlin; Shandler, Jeffrey; Fishman, David E. (1999). Profiles of a Lost World: Memoirs of East European Jewish Life Before World War II. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2784-5.

Before long there was a change of authority: Polish legionnaires under the command of General Lucian Zeligowski 'did not agree' with the peace treaty signed with Lithuania in Suwałki, which ceded Vilna to Lithuania.

- ↑ Michael Brecher; Jonathan Wilkenfeld (1997). A Study of Crisis. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-10806-0.

Mediation by the League Council led to an agreement on the 20th providing for a cease-fire and Lithuania's neutrality in the Polish-Russian War; Vilna remained part of Lithuania. The (abortive) Treaty of Suwałki, incorporating these terms, was signed on 7 October.

- ↑ Raymond Leslie Buell (2007). Poland – Key to Europe. Alfred Knopf, republished by Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-4564-1.

Clashes subsequently took place with Polish troops, leading to the armistice at Suwałki in October 1920 and the drawing of the famous Curzon Line under League mediation, which allotted Vilna to Lithuania.

- ↑ George Slocombe (1970). Mirror to Geneva. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8369-1852-6.

Zeligowski seized the city in October, 1920, in flagrant violation not only of the Treaty of Suwałki signed by Poland and Lithuania two days earlier, but also of the covenant of the newly created League of Nations.

- ↑ Müller, Jan-Werner (2002). Memory and Power in Post-War Europe: Studies in the Presence of the Past. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780521000703.

- ↑ Gross, Jan Tomasz (2002). Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia. Princeton University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-6910-9603-2.

- ↑ Ewelina Tylińska. "The revival of the Vilnius University in 1919: Historical conditions and importance for Polish science". The Global and the Local: The History of Science and the Cultural Integration of Europe. Proceedings of the 2nd ICESHS (Cracow, Poland, September 6–9, 2006)/Ed. by M. Kokowski. p. 896.

- ↑ Josef Krauski, Education as Resistance: The Polish Experience of Schooling During the War, in Roy Lowe, Education and the Second World War : studies in schooling and social change, Falmer Press, 1992, ISBN 0-7507-0054-8, Google Print, p. 130

- ↑ Snyder, Timothy (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780300128413.

- ↑ Yitzhak Arad, Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, vol. 4, p. 1572

- ↑ Stiklių-Žydų-Gaono Streets

- ↑ Mažasis ir Didysis Vilniaus žydų getai (Lithuanian)

- ↑ [Marrus, Michael R. The Holocaust in History. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1987, p. 108.]

- ↑ "Lithuania's first street honoring Holocaust Righteous unveiled in Vilnius | Jewish Telegraphic Agency". Jta.org. September 25, 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Kovos dėl Vilniaus 1944 liepą (Lithuanian)

- ↑ LIETUVOS NEPRIKLAUSOMOS VALSTYBĖS ATKŪRIMAS (1990 M. KOVO 11 D.) (Lithuanian)

- ↑ "Cultural capitals of Europe". Chicago Tribune. 11 January 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ↑ "O. Niglio, Restauri in Lituania. Vilnius Capitale della Cultura Europea 2009," (PDF). (810 KB) in "Web Journal on Cultural Patrimony", 1, 2006

- ↑ Greenhalgh, Nathan. "Capital of Culture: success or failure?". Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "A.Gelūnas: prokuratūra nusikaltimo rengiant Bjork koncertą neįžvelgė". Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Vilnius: artists protest 'breakdown of culture' in EU cultural capital". cafebabel.com.

- ↑ Burke, Jason (18 January 2009). "Eastern Europe braced for a violent 'spring of discontent'". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Balsavimo rezultatai". 2013.vrk.lt. 2015-03-22. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ http://old.vilnius.lt/newvilniusweb/index.php/116/?itemID=95357. Retrieved 22 October 2013. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Archived 27 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Drinking water in Lithuania is one of the best in Europe | The Lithuania TribuneThe Lithuania Tribune". Lithuaniatribune.com. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Andy G. "Water Vilnius Lithuania". Govilnius.com. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Eastern Partnership Summit in Vilnius begins

- ↑ Strategic Eastern Partnership agreements signed in Vilnius

- ↑ 12 of the world's most spectacular Christmas trees, By Tamara Hinson, for CNN

- ↑ Top 10 Christmas Displays In The World, essentialtravel.co.uk

- ↑ "The City". City of Vilnius. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ Kottek, M., J. Grieser, C. Beck, B. Rudolf, and F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130.

- ↑ Raymond S. Bradley; Philip D. Jones (1995). Climate Since A.D. 1500. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-12030-2.

- ↑ "Climate change in Lithuania". Lithuanian Hydrometeorological Service under the Ministry of Environment. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ↑ "World Weather Information Service – Vilnius". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Vilnius Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Vilnius, Lithuania". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ (Russian) г. Вильна Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г.

- 1 2 3 Der Große Brockhaus. 15th edition, vol. 20, Leipzig 1935, p. 348.

- 1 2 3 Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations, p. 92-93, 2003 New Haven & London, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-10586-5

- ↑ Vilnius Regional Statistical Office

- ↑ Statistics Department of Lithuania

- ↑ The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897. Breakdown of population by mother tongue and districts in 50 Governorates of the European Russia (1777 territorial units)

- ↑ Der Große Brockhaus. 15th edition, vol. 20, Leizig 1935, pp. 347–348.

- ↑ "Gyventojai pagal tautybę, gimtąją kalbą ir tikybą: Lietuvos Respublikos 2011 metų visuotinio gyventojų ir būstų surašymo rezultatai." (PDF). Lietuvos statistikos departamentas. 15 March 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "Population at the beginning of the year by administrative territory, Vilnius City Municipality". Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.lonelyplanet.com/lithuania/vilnius/sights/cemeteries-memorials-tombs/frank-zappa-memorial

- ↑ Vilnius Book Fair. Retried in 2009-02-14

- ↑ "Investment". City of Vilnius. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ↑ http://osp.stat.gov.lt/en/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?id=8446&status=A

- ↑ https://www.slideshare.net/mobile/VMS_2015/2016-m-atsakingas-vilniaus-biudetas-57262622

- ↑ "Darbo užmokestis". Statistics Lithuania. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ "Gyventojai pagal religinę bendruomenę, kuriai jie save priskyrė, savivaldybėse". Statistics Lithuania. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- ↑ Geggel, Laura (August 3, 2015). "Remains of Synagogue Destroyed by Nazis Found With Radar". nbcnews.com. LiveScience. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- ↑ "New Life in Karaim Communities". Euronet.nl. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ↑ "By Location". Adherents.com. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ↑ Gabriel Ignatow (2007). Transnational Identity Politics and the Environment. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2015-6.

- ↑ "Užupis Old Jewish Cemetery [Užupio Senosios Žydų Kapinės]". In Your Pocket. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ↑ "В Вильнюсе на монументе в память о еврейском кладбище нарисовали свастику". DELFI. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ↑ Bernardinai garden opened his gates after reconstruction (Lithuanian)

- ↑ "LFF stadionas". LFF. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ↑ "Go Swimming". Vilnius Monthly. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ↑ "Federation of International Bandy-About-About FIB-National Federations-Lithuania-Lithuania". Internationalbandy.com. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos badmintono federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos baidarių ir kanojų irklavimo federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos beisbolo asociacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos biatlono federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos buriuotojų sąjunga | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos futbolo federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos fechtavimo federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos dviračių sporto federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos lankininkų federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos lengvosios atletikos federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos ledo ritulio federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos krepšinio federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos kerlingo federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos irklavimo federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos imtynių federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos greitojo čiuožimo asociacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos gimnastikos federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos žirginio sporto sąjunga | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos šiuolaikinės penkiakovės federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos šaudymo sporto sąjunga | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos triatlono federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos tinklinio federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos teniso sąjunga | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos taekwondo (wtf) federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos sunkiosios atletikos federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos stalo teniso asociacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos nacionalinė slidinėjimo asociacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos regbio federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "Lietuvos plaukimo federacija | LTOK". Ltok.lt. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ Vanagas, Jurgis. "Navigation on the Neris River and its importance for Vilnius". Journal of Sustainable Architecture and Civil Engineering. 4 (13): 62–69. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ "Social and Economic Analysis of the Demand for Public Transport in Vilnius" (PDF). Vilnius Gediminas Technical University. 2003. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ Vilnius public transport e-ticket system

- ↑ Dumalakas, Arūnas (14 June 2014). "Vilnius palaidojo tramvajaus ir metro idėjas" [Vilnius has buried the tram and metro ideas]. lrytas.lt (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos Rytas. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ "Miestai partneriai | Vilnius | Apie Vilnių | iVilnius.lt - Vilniaus miesto gidas". iVilnius.lt. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Aalborg Twin Towns". Europeprize.net. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ "Sister cities of Budapest". Official Website of Budapest (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "Cities Twinned with Duisburg". duisburg.de. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ↑ "List of Twin Towns in the Ruhr District". 2009 Twins2010.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Gdańsk Official Website: 'Miasta partnerskie'" (in Polish and English). [[copyright|]] 2009 Urząd Miejski w Gdańsku. Retrieved 11 July 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Guangzhou Sister Cities [via WaybackMachine.com]". Guangzhou Foreign Affairs Office. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ "Kraków – Miasta Partnerskie" [Kraków -Partnership Cities]. Miejska Platforma Internetowa Magiczny Kraków (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Miasta partnerskie – Urząd Miasta Łodzi [via WaybackMachine.com]". City of Łódź (in Polish). Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ "Vilnius ir Lvovas pasirašė bendradarbiavimo sutartį | kl.lt" (in Lithuanian). Klaipeda.diena.lt. 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Taipei – International Sister Cities". Taipei City Council. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ↑ "Tbilisi Sister Cities". Tbilisi City Hall. Tbilisi Municipal Portal. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013. External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ "TREND: Tbilisi, Vilnius become brother cities". en.trend.az. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- ↑ "Miasta partnerskie Warszawy". um.warszawa.pl. Biuro Promocji Miasta. 4 May 2005. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- ↑ Margolis, Rachel (1 April 2010). A Partisan from Vilna. Academic Studies Press. ISBN 9781934843956.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vilnius. |

- The Jerusalem of Lithuania: The Story of the Jewish Community of Vilna an online exhibition by Yad Vashem

Vilnius travel guide from Wikivoyage

Vilnius travel guide from Wikivoyage- Vilnius from bird flight

- Comprehensive photo gallery of Vilnius by Baltic Reports editor

- Video preview of Vilnius Capital of Culture

- Virtual Historical Vilnius

- Public transportation schedules and timetables in Vilnius

- Erasmus in Vilnius and info

.png)

.jpg)