Brussels and the European Union

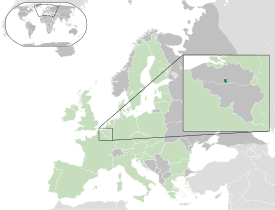

Brussels in Belgium is considered[1] the de facto capital of the European Union,[2] having a long history of hosting the institutions of the European Union within its European Quarter. The EU has no official capital, and no plans to declare one, but Brussels hosts the official seats of the European Commission, Council of the European Union, and European Council, as well as a seat (officially the second seat but de facto the most important one) of the European Parliament.

History

| Brussels |

This article is part of the series: |

Parties

|

Issues

|

Two chances

In 1951, the leaders of six European countries (Belgium, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, France, Italy and West Germany) signed the Treaty of Paris which created the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), and with this new community came the first institutions: the High Authority, Council of Ministers, Court of Justice and Common Assembly. A number of cities were considered, and Brussels would have been accepted as a compromise, but the Belgian government put all its effort into backing Liège,[3] opposed by all the other members, and was unable to formally back Brussels due to internal instability.[4]

Agreement remained elusive and a seat had to be found before the institutions could begin work, hence Luxembourg was chosen as a provisional seat, though with the Common Assembly in Strasbourg as that was the only city with a large enough hemicycle (the one used by the Council of Europe). This agreement was temporary, and plans were set to relocate the institutions to Saarbrücken which would serve as a "European District", but this did not occur.[5][6]

The 1957 Treaties of Rome established two new communities, the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom). These shared the Assembly and Court of the ECSC but created two new sets of Councils and Commissions (equivalent to the ECSC's High Authority). Discussions on the seats of the institutions were left till the last moment before the treaties came into force, so as not to interfere with ratification.[7]

Brussels waited until only a month before talks to enter its application, which was unofficially backed by several member states. The members agreed in principle to locate the executives, councils and the assembly in one city, though could still not decide which city, so they put the decision off for six months. In the meantime, the Assembly would stay in Strasbourg and the new commissions would meet alternatively at the ECSC seat and at the Château of Val-Duchesse, in Brussels (headquarters of a temporary committee). The Councils would meet wherever their Presidents wanted to.[8] In practice, this was the Castle in Brussels until autumn 1958 when it moved to central Brussels: 2 Rue Ravensteinstraat.[9]

Early expansion

Brussels missed out in its bid for a single seat due to a weak campaign from the government in negotiations, despite widespread support from the people. The Belgian government eventually pushed its campaign and started large-scale construction, renting office space in the east of the city for use by the institutions. On 11 February 1958, the six governments concluded an unofficial agreement on the setting-up of community offices. On the principle that it would take two years after a final agreement to prepare the appropriate office space, full services were set up in Brussels in expectation of a report from the Committee of Experts looking into the matter of a final seat.[10]

While waiting for the completion of the building on Avenue de la Joyeuse Entrée/Blijde Inkomstlaan, offices moved to 51–53 Rue Belliard (Belliardstraat) on 1 April 1958 (later exclusively used by the Euratom Commission), though with the numbers of civil servants rapidly expanding, services were set up in buildings on Rue de Marais/Broekstraat, Avenue de Broquevillelaan, Avenue de Tervuerenlaan, Rue d'Arlon/Aarlenstraat, Rue Joseph II/Jozef II-straat, Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat and Avenue de Kortenberglaan. The Belgian government further provided newly built offices on the Mont des Arts/Kunstberg (22 Rue des Sols/Stuiversstraat) for the Council of Ministers' Secretariat and European Investment Bank.[11][12]

A Committee of Experts deemed Brussels to be the one option to have all the necessary features for a European capital: a large, active metropolis, without a congested centre or poor quality of housing; good communications with other member states' capitals, including to major commercial and maritime markets; vast internal transport links; an important international business centre; plentiful housing for European civil servants; and an open economy. Furthermore, it was located on the border between the two major European civilisations, Latin and Germanic, and was at the centre of the first post-war integration experiment: the Benelux. As a capital of a small country, it also could not claim to use the presence of institutions to exert pressure on other member states, it being more of a neutral territory between the major European powers. The Committee's report was approved of by the Council, Parliament and Commissions, however the Council was still unable to achieve a final vote on the issue and hence put off the issue for a further three years despite all the institutions now leading in moving to Brussels.[13]

The decision was put off due to the varied national positions preventing a unanimous decision. Luxembourg fought to keep the ECSC or have compensation, France fought for Strasbourg and Italy, initially backing Paris, fought for any Italian city to thwart Luxembourg and Strasbourg. Meanwhile, Parliament passed a series of resolutions complaining about the whole situation of spreading itself across three cities, though unable to do anything about it.[14]

Merger

The 1965 Merger Treaty was seen as an appropriate moment to finally resolve the issue, the separate Commissions and Councils were to be merged. Luxembourg, concerned about losing the High Authority, proposed a split between Brussels and Luxembourg. The Commission and Council in the former with Luxembourg keeping the Court and Parliamentary Assembly, together with a few of the Commission's departments. This was largely welcomed but opposed by France, not wishing to see the Parliament leave Strasbourg, and by Parliament itself which wished to be with the executives and was further annoyed by the fact it was not consulted on the matter of its own location.[15]

Hence, the status quo was maintained with some adjustments; The Commission, with most of its departments, would be in Brussels. As would the Council, but in April, June and October it would meet in Luxembourg. In addition, Luxembourg would keep the Court of Justice, some of the Commission's departments and the secretariat of the European Parliament. Strasbourg would continue to host Parliament.[16][17][18] Joining the Commission was the merged Council secretariat. The ECSC secretariat merged with the EEC's and EAEC's in the Ravenstein building which then moved to the Charlemagne building, next to the Berlaymont, in 1971.[9]

In Brussels, staff continued to be spread across a number of buildings, on the Rue Belliardstraat, Avenue de la Joyeuse Entrée/Blijde Inkomstlaan, Rue du Marais/Broekstraat and at Mont des Arts/Kunstberg.[18] The first purpose-built building was the Berlaymont building in 1958, designed to house 3000 officials which soon proved too small, causing the institution to spread out across the neighbourhood.[19]

Yet, despite the agreement to host these institutions in Brussels, its formal status was still unclear, and hence the city sought to strengthen its hand with major investment in buildings and infrastructure (including the Brussels Metro: Schuman station). However, these initial developments were sporadic with little town planning and based on speculation.[19] (See: Brusselisation)

However, the 1965 agreement was a source of contention for the Parliament, which wished to be closer to the other institutions, so it began moving some of its decision making bodies, committee and political group meetings to Brussels.[20] In 1983 it went further by symbolically holding a plenary session in Brussels, in the basement of the Mont des Arts Congress Centre. However the meeting was a fiasco and the poor facilities partly discredited Brussels' aim of being the sole seat of the institutions.[21] Things looked up for Brussels when Parliament gained its own plenary chamber in Brussels (on Rue Wiertzstraat) in 1985 for some of its part-sessions.[20] This was done unofficially due to the sensitive nature of the Parliament's seat, with the building being constructed under the name of an "international conference centre".[19] When France unsuccessfully challenged Parliament's half-move to Brussels in the Court of Justice, Parliament's victory led it to build full facilities in Brussels.[22]

Edinburgh and the European Council

In response the Edinburgh European Council of 1992 adopted a final agreement on the location of the institutions. According to this decision, which was subsequently annexed to the Treaty of Amsterdam,[20] although Parliament was required to hold some of its sessions, including its budget session, in Strasbourg, extra sessions and committees could meet in Brussels. It also reaffirmed the presence of the Commission and Council in the city.[23]

Shortly before this summit, the Commission moved into the Breydel building. This was due to asbestos being discovered in the Berlaymont, forcing its evacuation in 1989. The Commission threatened to move out of the city, which would have destroyed Brussels's chances of hosting the Parliament, so the government stepped in to build the Breydel building a short distance from the Berlaymont in 23 months, ensuring the Commission could move in before the Edinburgh summit. Shortly after Edinburgh, Parliament bought its new building in Brussels. With the status of Brussels now clear, NGOs, lobbyists, advisory bodies and regional offices started basing themselves in the quarter near the institutions.[19]

The Council, which had been expanding into further buildings as it grew, consolidated once more in the Justus Lipsius building,[9] and in 2002 it was agreed that the European Council should also be based in Brussels, having previously moved between different cities as the EU's Presidency rotated. From 2004 all Councils were meant to be held in Brussels; however, some extraordinary meetings are still held elsewhere. The reason for the move was in part due to the experience of the Belgian police in dealing with protesters and the fixed facilities in Brussels.[24]

Status

The Commission employs 25,000[25] people and the Parliament employs about 6,000 people.[26] Because of this concentration, Brussels is a preferred location for any move towards a single seat for Parliament.[27][28] Despite it not formally being the "capital" of the EU, some commentators see the fact that Brussels enticed an increasing number of Parliament's sessions to the city, in addition to the main seats of the other two main political institutions, as making Brussels the de facto capital of the EU.[29] Brussels is frequently labelled as the 'capital' of the EU, particularly in publications by local authorities, the Commission and press.[30][31][32][33][34][35] Indeed, Brussels interprets the 1992 agreement on seats (details below) as declaring Brussels as the capital.[30]

There are two further cities hosting major institutions, Luxembourg (judicial and second seats) and Strasbourg (Parliament's main seat). Authorities in Strasbourg and organisations based there also refer to Strasbourg as the "capital" of Europe[36][37][38] and Brussels, Strasbourg and Luxembourg are also referred to as the joint capitals of Europe.[34] In 2010, Vice President of the United States Joe Biden, while speaking to the European Parliament, stated that Brussels, like Washington D.C. had its own claim to be capital of the free world.[39][40]

Lobbyists and journalists

Like Washington D.C., Brussels is a centre of political activity with ambassadors to Belgium, NATO and the Union being based in the city; with there being more ambassadors based in the city than in the US capital. There's also a greater number of press corps in Brussels with media outlets in every Union member-state having a Brussels correspondent and there are 10,000 lobbyists registered.[25]

Of the 1200 accredited journalists in Brussels, 1000 are from outside Belgium, 120 of these are from Germany alone (compared to 20–30 in Washington D.C.) however there has been a disproportionately small representation of US press in Brussels, with very few newspapers having correspondents based in the city.[41]

Accessibility

Brussels is located in the urban centre of Europe, between Paris, London, Rhine and Ruhr, and the Randstad. Via high speed trains Brussels is around 1h25 from Paris, 1h50 from London, Amsterdam and Cologne (with adjacent Düsseldorf and Rhine-Ruhr), 3h from Frankfurt.

The "Eurocap-rail" project plans to improve Brussels' links to the south to Luxembourg city and Strasbourg.[34] Brussels is also served by Brussels Airport, located in the nearby Flemish municipality of Zaventem, and by the smaller Brussels South Charleroi Airport, located near Charleroi (Wallonia), some 50 km (30 mi) from Brussels.

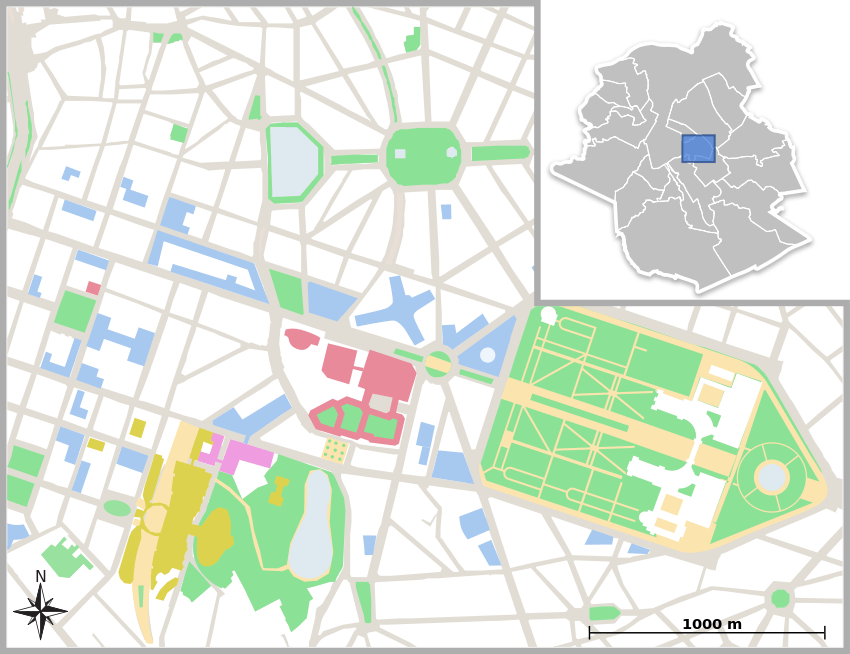

Quarter

Most of the institutions are located within the European Quarter of Brussels, which is the unofficial name of the area corresponding to the approximate triangle between Brussels Park, Cinquantenaire Park and Leopold Park (with the Parliament's hemicycle extending into the latter). The Commission and Council are located in the heart of this area near to the Schuman station at the Schuman roundabout on the Rue de la Loi. The European Parliament is located over the Brussels-Luxembourg station, next to Luxembourg Square.[18]

The area, much of which was known as the Leopold Quarter for much of its history, was historically residential, an aspect which was rapidly lost as the institutions moved in, although the change from a residential area to a more office oriented one had already been underway for some time before the arrival of the European institutions.[42] Historical and residential buildings, although still present, have been largely replaced by modern offices. These buildings were built not according to a high quality master plan or government initiative, but according to speculative private sector construction of office space, without which most buildings of the institutions would not have been built.[43] However, due to Brussels's attempts to consolidate its position, there was large government investment in infrastructure in the quarter.[19] Authorities are keen to stress that the previous chaotic development has ended, being replaced by planned architecture competitions[44] and a master plan (see "future" below).[45] Architect Benoit Moritz has argued that the area has been an elite enclave surrounded by poorer districts since the mid-19th century, and that the contrast today is comparable to an Indian city. However, he also said that the city has made progress over the last decade in mixing land uses, bringing in more businesses and residences, and that the institutions are more open to "interacting" with the city.[46]

Palmerston

Square

Ambiorix

Marguerite

Square

Meeûs

The quarter's land-use is very homogenous and criticised by some, for example former Commission President Romano Prodi, for being an administrative ghetto isolated from the rest of the city (though this view is not shared by all). There is also a perceived lack of symbolism, with some such as Rem Koolhaas proposing that Brussels needs an architectural symbol to represent Europe (akin to the Eiffel Tower or Colosseum). Others do not think this is in keeping with the idea of the EU, with Umberto Eco viewing Brussels as a "soft capital"; rather than it being an "imperial city" of an empire, it should reflect the EU's position as the "server" of Europe.[44] Despite this, the plans for redevelopment intend to deal with a certain extent of visual identity in the quarter.[45]

Commission buildings

The most iconic structure is the Berlaymont, the primary seat of the Commission. It was the first building to be constructed for the Community, originally built in the 1960s. It was designed by Lucien De Vestel, Jean Gilson, André Polak and Jean Polak and paid for by the Belgian government (who could occupy it if the Commission left Brussels). It was inspired by the UNESCO headquarters building in Paris, designed as a four-pointed star on supporting columns, and at the time an ambitious design.

Originally built with flock asbestos, the building was renovated in the 1990s to remove it and renovate the ageing building to cope with enlargement. After a period of exile in the Breydel building on the Avenue d'Auderghem/Oudergemlaan, the Commission reoccupied the Berlaymont in 2005 and bought the building for €550 million.

The president of the Commission occupies the largest office, near the Commission's meeting room on the top (13th) floor. Although the main Commission building, it houses only 2,000 out of the 20,000 Commission officials based in Brussels. In addition to the Commissioners and their cabinets, the Berlaymont also houses the Commission's Secretariat-General and Legal Service. Across the quarter the Commission occupies 865,000 m2 (9,310,783 sq ft) in 61 buildings with the Berlaymont and Charlemagne buildings the only ones over 50,000 m2 (538,196 sq ft).

Other institutions

Across the Rue de la Loi from the Berlayont is the Justus Lipsius building which houses the Council of the European Union and the European Council. The Council's secretariat had originally been based in the city centre, and then in the Charlemagne building joining the other European buildings centred on the Schuman roundabout.[17][18] The European Council will move info Résidence Palace next door once it has been renovated and the Lex building beyond that was occupied by the Council in 2007.[47] The renovation and construction of the new Council building was intended to change the image the European quarter, and is designed by the architect Philippe Samyn to be a "feminine" and "jazzy" building to contrast with the hard, more "masculine" architecture of other EU buildings.[46] The building features a "lantern shaped" structure surrounded by a glass atrium made up of recycled windows from across Europe, intended to appear "united from afar but showing their diversity up close."[46]

The Parliament's buildings are located to the south between Leopold Park and Luxembourg Square, over Brussels-Luxembourg Station which is underground. The complex, known as the "Espace Léopold" (or "Leopoldsruimte" in Dutch), has two main buildings: Paul-Henri Spaak and Altiero Spinelli which cover 372,000 m2 (4,004,175 sq ft). The complex is not the official seat of the Parliament with its work being split with Strasbourg (its official seat) and Luxembourg (its secretariat). However the decision making bodies of the Parliament, along with its committees and some of its plenary sessions, are held in Brussels to the extent that three quarters of its activity take place in Brussels.[48] The Parliament buildings were extended with the new D4 and D5 buildings being completed and occupied in 2007 and 2008. It is believed the complex now provides enough space for Parliament with no major new building projects foreseen.[47]

The European External Action Service has been based in the Triangle building since 1 December 2010.

The Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions together occupy the Delors building, which is next to Leopold Park and used to be occupied by the Parliament. They also use the office building Bertha von Suttner. Both buildings were named in 2006.[49][50] Brussels also hosts two agencies, the European Defence Agency (located on Rue des Drapiers/Lakenweversstraat) and the Executive Agency for Competitiveness and Innovation – (in Madou Tower). There is also EUROCONTROL, a semi-EU air traffic control agency covering much of Europe and the Western European Union which is a non-EU military organisation which is merging into the EU's CFSP.

Demography and economic impact

The EU presence in Brussels has created significant social and economic impact. Jean-Luc Vanraes, member of the Brussel parliament responsible for the city's external relations, goes as far to say the prosperity of Brussels "is a consequence of the European presence". As well as the institutions themselves, large companies are drawn to the city due to the EU presence. In total about 10% of the city has a connection to the international community.[51]

46% of the population of Brussels are from outside Belgium;[52] of these, half are from other EU member states. About 3/5 of European Civil Servants live in the Brussels Capital Region with 63% in the communes around the European district (24% in the Flemish region to the north and 11% in the Walloon region to the south).[53] Half of civil servants are home owners. The institutions draw in, directly employed and employed by representatives, 50,000 people to work in the city. A further 20,000 people are working in Brussels due to the presence of the institutions (generating €2 billion a year) and 2000 foreign companies drawn into the city employ 80,000 multilingual locals.[54]

In Brussels, there are 3.5 million square meters of occupied office space; half of this is taken up by the EU institutions alone, accounting for a quarter of available office space in the city. The majority of EU office space is concentrated in the Leopold quarter. Running costs of the EU institutions total €2 billion a year, half of which benefit Brussels directly, and a further €0.8 come from the expenses of diplomats, journalists etc. Business tourism in the city generates 2.2 million annual hotel room nights. There are thirty international schools (15,000 pupils run by 2000 employees) costing €99 million a year.[54]

However, there is considerable division between the two communities, with local Brussels residents feeling excluded from the EU quarter (a "white collar ghetto"). The communities often do not mix much, with expats having their own society. This is in part down to that many expat in Brussels stay for short periods only and do not always learn the local languages (supplanted by English/Globish), remaining in expat communities and sending their children to European Schools, rather than local Belgian ones.[52][53][55]

Future

Rebuilding

In September 2007, the Commissioner for Administrative Affairs Siim Kallas, together with Minister-President of the Brussels-Capital Region Charles Picqué, unveiled plans for rebuilding the district. It would involve new buildings (220,000 m2 (2,368,060 sq ft) of new office space) but also more efficient use of existing space. This is primarily through replacing numerous smaller buildings with fewer, larger, buildings.[45]

In March 2009, a French-Belgian-British team led by French architect Christian de Portzamparc won a competition to redesign the Wetstraat/Rue de la Loi between Maalbeek/Maelbeek Garden and Residence Palace in the east to the small ring in the west. Siim Kallas stated that the project, which would be put into action over a few a long period rather than all at once, would create a "symbolic area for the EU institutions" giving "body and soul to the European political project" and providing the Commission with extra office space. The road would be reduced from four lanes to two, and be returned to two way traffic (rather than all west-bound) and the architects proposed a tram line to run down the centre. A series of high rise buildings would be built on either side with three taller 'flagship' high rises at the east end on the north side. Charles Picqué described the towers as "iconic buildings that will be among the highest in Brussels" and that "building higher allows you to turn closed blocks into open spaces."[56][57] The tallest buildings will be up to 80 metres high, though most between 16 and 55, but the higher the building the further back it will be set from the road.[58] The freed up space (some 180,000m²) would be given over to housing, shops, services and open spaces to give the area a more "human" feel.[45] A sixth European School may also be built. On the western edge of the quarter, on the small ring, there would be "gates to Europe" to add visual impact.[59]

Given the delays and cost of the Berlaymont and other projects, the Commissioner emphasises that the new plans would offer "better value for money" and that the designs would be subject to an international architecture competition. He also pushed that controlling the buildings carbon footprint would be "an integral part of the programme".[45]

As of 2015 two high-profile EU buildings are under construction in the area: the new Council building and a "House of European History" in Leopold Park.[46] The new Council building was supposed to follow the new model for the area. The design chosen was the result of an international architectural competition and it was intended to be more iconic as well as open to the public. However, due to security restrictions the design remains largely closed to the public, and the cancellation of a planned pedestrianised public area in front of it will hamper its integration into the area according to critics.[46]

Pedestrian squares

There were plans to pedestrianise of part of the Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat next to the Berlaymont.[60] A new Place Schumanplein (currently the Schuman roundabout) would be one of three new pedestrian squares. Schuman would focus on "policy and politics"[59] and Schuman station itself will be redesigned.[61] Coverings over nearby motorways and railways would be extended to shield them from view.[59] However, the planned pedestrianisation of the Schuman roundabout were cancelled in late 2014.[46]

A pedestrian and visual link would be created between the Berlaymont and Leopold park by demolishing sections of the ground to fourth floors of Justus Lipsius, the south "bland" façade of which would be redesigned. Further pedestrian and cycle links would be created around the quarter. Pedestrian routes would also be created for demonstrations.[59] Next to the Parliament at Leopold Park, the block of buildings between Rue d'Arlon/Aarlenstraat and Rue de Trêves/Trierstraat would be removed, creating a broad boulevard-like extension[62] of Luxembourg Square, the second pedestrian square (focusing on citizens).[59]

The third pedestrian square would be the "Esplanade du Cinquantenaire" or "Esplanade van het Jubelpark" (for events and festivities).[63] Wider development may also surround Cinquantenaire Park with plans for a new metro station, underground car park and the Europeanisation of part of the Cinquantenaire complex with a "socio-cultural facility". It is possible that the European Council may have to move to this area from Résidence Palace for security reasons.[59]

Further-quarters

The concentration of offices in the main quarter has led to increase real estate prices due to the increased demand and reduced space. In response to this problem the Commission has, since 2004, begun decentralising across the city to areas such as avenue de Beaulieulaan (50°48′51″N 4°24′44″E / 50.81425°N 4.4122°E) in Auderghem and rue de Genèvestraat (50°51′50″N 4°24′12″E / 50.864°N 4.4033°E) in Evere.[64][65] This has reduced price increases but it is still one of the most expensive areas in the city (€295 per square metre, compared to €196 per on average).[64][65] Neither Parliament or the Council have followed suit however and the policy of decentralisation is unpopular among the Commission's staff.[47]

Nevertheless, the Commission intends to develop two or three large "poles" outside the quarter, each greater than 100,000 m2 (1,076,391 sq ft).[66] Heysel Park (50°53′42″N 4°20′29″E / 50.8949°N 4.3415°E) has been proposed as one of the new poles by the City of Brussels, which intends to develop the area as an international district regardless. The park, built around the Atomium landmark, already hosts a European School, has the largest parking facilities in Belgium, a metro station, an exhibition hall and the 'Mini-Europe' park. The city intends to build an international conference centre with 3,500 seats and an "important commercial centre." The Commission will respond to the proposal in the first half of 2009.[67]

As for the existing Beaulieu pole, which is to the south east of the main European quarter, there is a proposal to link it with the main quarter by covering the railway lines between Beaulieu and the European Parliament (the esplanade of which sits on top of the Brussels-Luxembourg railway station). Traffic on the lines is expected to increase creating environmental problems that would be solved by covering the lines. The surface would then be covered by flagstones, in the same manner as Parliament's esplanade, to create a pedestrian/cyclist path between the two districts. The plan proposes that this "promenade of Europeans" of 3720 metres be divided into areas dedicated to each of the member states.[68]

Political status

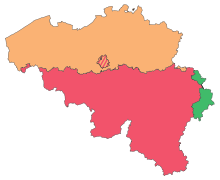

Belgium currently operates a complex federal system between the two main groups: Flemish and Walloons. There's a division of Belgium into three regions, where Brussels-Capital Region is an independent region, next to Flanders and Wallonia. The regions are mostly responsible for the economy, mobility and other territory-related matters. But there's also a division of Belgium into three communities: the Flemish Community, the French Community and the German-speaking Community. These communities are responsible for language-related matters like culture or education. Brussels doesn't belong to any community, but has a bilingual status. So the Brussels inhabitants may enjoy education or cultural affairs or education organised by the Flemish and/or the French community.

This structure is the result of many compromises in the political spectrum going from separatism to unionism, while also combining the wishes of the Brussels population to have a degree of independence, and the wishes of the Flemish and Walloon population to have a level of influence in Brussels. It has been criticised by some but the system has also been compared to the EU, as a "laboratory of Europe".

In the unlikely event of complete independence of a region, the future status of the city is unknown and problematic, but some have suggested it become a "European capital district", like Washington D.C. or the Australian Capital Territory, run by the EU rather than Flanders or Wallonia.[69][70] However, unlike these it would also be likely that Brussels itself would be an EU member state.[71] The possible status of Brussels as a "city state" has also been suggested by Charles Picqué, former Minister-President of the Brussels-Capital Region, who sees a tax on the EU institutions as a way of enriching the city. However, the Belgian issue has very little discussion within the EU bodies.[72]

The boundaries of the Brussels-Capital Region were determined from the 1947 language census data. This was the last time that some municipalities were converted from a monolingual Dutch into a bilingual municipality, and were joined with the Brussels agglomeration. The suggestive nature of the questions led massive protest in Flanders (especially around Brussels), causing it to be unlikely to ever have language-related census data again in Belgium. The result is that the Brussels-Capital region is now a lot smaller than the French influence around the capital, and that there's no place in Brussels for important infrastructure. Enlarging the territory of Brussels could potentially give it around 1.5 million inhabitants, an airport, a bigger forest, and bring the Brussels Ringroad on Brussels territory. A large and independent status may help Brussels in its claim as the capital of the EU.[71] However, this is highly unlikely to happen in the near future.

See also

- Brussels-Capital Region

- Commissioner for Administrative Affairs

- Council of the European Union#Seat

- European Commission

- European Institutions in Strasbourg

- European Justice

- European Parliament

- History of the European Union

- Institutions of the European Union

- Leopold Quarter

References

- Demey, Thierry (2007). Brussels, capital of Europe. S. Strange (trans.). Brussels: Badeaux. ISBN 2-9600414-2-9.

- ↑ see the references below in the Status section

- ↑ Cybriwsky, Roman Adrian (2013). Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture. ABC-CLIO.

Brussels, the capital of Belgium, is considered to be the de facto capital of the EU

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 175–6

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 177

- ↑ The plan was that it would be a "European district" between France and Germany, and institutions would move when the status was agreed. But three years later Saarbrücken voted massively to rejoin West Germany, cancelling the European district plan and maintaining Luxembourg's position.

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 178–9

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 187

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 187–8

- 1 2 3 "Seat of the Council of the European Union". CVCE. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 190–3

- ↑ The EIB moved to Luxembourg in 1965

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 193

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 196–8

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 199

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 205–6

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 207

- 1 2 Seat of the European Commission on CVCE website

- 1 2 3 4 European Commission publication: Europe in Brussels 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 The European Quarter, Brussels-Europe Liaison Office (2008-07-20)

- 1 2 3 "The seats of the institutions of the European Union". CVCE. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 209–10

- ↑ Demey, 2007: 211–2

- ↑ European Council (12 December 1992). "Decision taken by Common Agreement between the representatives of the governments of member states on the location of the seats of the institutions and of certain bodies and departments of the European Communities.". European Parliament. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ Stark, Christine. "Evolution of the European Council: The implications of a permanent seat" (PDF). Dragoman.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- 1 2 All above figures from E!Sharp magazine, Jan–Feb 2007 issue: Article "A tale of two cities".

- ↑ Parliament's website europarl.europa.eu

- ↑ "OneSeat.eu: 1 million citizens do care". Young European Federalists. 18 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ↑ Wallström, Margot (24 May 2006). "My blog: Denmark, Latvia, Strasbourg". European Commission. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Demey, 2007

- 1 2 "Brussels: capital of Europe". Brussels-Europe Liaison Office. 6 April 2006. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ Gilroy, Harry (2 June 1962). "Big Day for Brussels; Common Market Activities Make City The New Capital of European Politics". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ "Prodi and Verhofstadt present ideas for Brussels as capital of Europe". Euractv. 5 April 2007. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ Demey, Thierry (2007). Brussels, capital of Europe. S. Strange (trans.). Brussels: Badeaux. ISBN 2-9600414-2-9.

- 1 2 3 Laconte, Pierre; Carola Hein (2008). Brussels: Perspectives on a European Capital. Brussels, Belgium: Foundation for the Urban Environment. ISBN 978-2-9600650-0-8.

- ↑ Europe in Brussels (in English, French, Dutch, and German). European Commission. 2007.

- ↑ "Strasbourg : the European capital". Strasbourg Tourism Office. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ "Alliance Française Strasbourg Europe". Alliance française. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ "Strasbourg, capitale européenne". Le Pôle européen d'administration publique. 2005. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ "Biden Says Brussels Could Be 'Capital of the Free World'". Fox News. 25 May 2010.

- ↑ americanthinker.com

- ↑ Harding, Garath (23 July 2007). "Not over here". This Europe. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ↑ Demey, Thierry (2007). Brussels, Capital of Europe. Brussels: Badeaux. p. 72.

The gradual metamorphosis from residential area to office district started in earnest after the 1958 World Fair with the arrival of the first European civil servants. However, the progressive exodus of the population to the leafy communes and their replacement by commercial company headquarters had already begun at the dawn of the century.

- ↑ Demey, 2007: p.216-7

- 1 2 Zucchini, Giulio (18 October 2006). "Brussels, a soft capital". Café Babel. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "EU promises 'facelift' for Brussels' European quarter". EurActiv. 6 September 2007. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vermeersch, Laurent (30 January 2015). "Is the EU's new council building a desperate attempt to change its image?". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 Rankin, Jennifer (31 October 2007). "City bids to shape EU's presence". European Voice. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Wheatley, Paul (2 October 2006). "The two-seat parliament farce must end". Café Babel. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ↑ Bertha von Suttner – a visionary European. Opening of Bertha von Suttner Building, Committee of the Regions – ECOSOC. Brussels, 8 March 2006 europa.eu

- ↑ The EESC and CoR building at 99–101 rue Belliardstraat renamed Jacques Delors Building europa.eu

- ↑ Banks, Martin (29 June 2010) EU responsible for significant' proportion of Brussels economy, The Parliament Magazine. Accessed 1 July 2010

- 1 2 Bocart, Stéphanie (12 June 2010) Invasion of the Eurocrats, La Libre Belgique, on PressEurop. Accessed 1 July 2010

- 1 2 Meulders, Raphael (22 June 2010) Brussels has also become our town, La Libre Belgique via Google Translate. Accessed 1 July 2010

- 1 2 Demey, Thierry (2007). Brussels, capital of Europe. translated by Sarah Strange. Badeaux. pp. 7–8. ISBN 2-9600414-2-9.

- ↑ Meulders, Raphael (21 June 2010) to "Euroland", La Libre Belgique via Google Translate. Accessed 1 July 2010

- ↑ Brussels' EU quarter set for 'spectacular' facelift, EurActive

- ↑ "Annonce du lauréat de la compétition visant la Définition d'une forme urbaine pour la rue de la Loi et ses abords" (PDF). Charlespicque.be (in French). 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009.

- ↑ Buildings that speak ‘to Europe and the world', European Voice 12.03.09

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Clerbaux, Bruno. "The European Quarter today: Assessment and prospects" (PDF). European Council of Spatial Planners. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ Laconte, Pierre; Carola Hein (5 September 2007). "Brussels: Perspectives on a European Capital" (PDF). Foundation for the Urban Environment. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Bavière, Francis Vanden (9 December 2007). "A peek on the future Schuman Station". iFrancis. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ "Bruxelles et l'UE prépare un grand lifting pour la Rue de la Loi". RTL. 5 September 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

- ↑ Brussel Nieuws. Brussel verruimd de horizon. Retrieved on 2007-12-11

- 1 2 "European Commission buildings policy – questions and answers". EU Business. 6 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- 1 2 Vucheva, Elitsa (5 September 2007). "EU quarter in Brussels set to grow". EU Observer. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ↑ Kallas, Siim (10 April 2008). "Speech of Vice-President Kallas: Designing for the Future – The Market and the Quality of Life" (PDF). Architects' Council of Europe. Archived from the original (pdf) on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ↑ Pop, Valentina (9 January 2009). "EU commission considers major relocation in Brussels". EU Observer. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ↑ Promenade des Européens, EuroBru

- ↑ McKinsey CEO Calls for End of Belgium, Resigns Brussels Journal

- ↑ Crisis in Belgium: If Flanders Secedes Wallonia Disintegrates Brussels Journal

- 1 2 Van Parijs, Philippe (4 October 2007). "Brussels after Belgium: fringe town or city state ?" (PDF). The Bulletin. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ↑ Feki, Donya (29 November 2007). "Jean Quatremer: a nation has been born – Flanders". Café Babel. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to EU in Brussels. |

- European Quarter on Wikimapia

- (French) Le Plan de Développement International de Bruxelles

- (French) bruxelles.irisnet.be or (Dutch) brussel.irisnet.be: Future plans for the European Quarter, Brussels-Capital Region

- Google Maps, Robert Schuman

- Map of the EU area

- Brussels International Brussels Tourism

- Visit the European Parliament

- (French) Parliament D4 & D5 buildings

- Gallery of the EU Quarter

- The Brussels-Europe Liaison Office, a body charged to promote Brussels as Europe's capital

- Statistics on the EU presence in Brussels, Brussels-Europe Liaison Office

- Foundation for the Urban Environment

Coordinates: 50°50′N 4°23′E / 50.84°N 4.38°E