Coullemelle

| Coullemelle | |

|---|---|

| |

Coullemelle | |

|

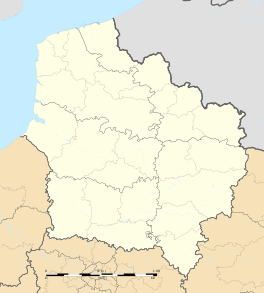

Location within Hauts-de-France region  Coullemelle | |

| Coordinates: 49°40′07″N 2°25′26″E / 49.6686°N 2.4239°ECoordinates: 49°40′07″N 2°25′26″E / 49.6686°N 2.4239°E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Hauts-de-France |

| Department | Somme |

| Arrondissement | Montdidier |

| Canton | Ailly-sur-Noye |

| Intercommunality | Val de Noye |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2001–2008) | Nicolas Lavoine |

| Area1 | 9.32 km2 (3.60 sq mi) |

| Population (2006)2 | 238 |

| • Density | 26/km2 (66/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 80214 / 80250 |

| Elevation |

100–156 m (328–512 ft) (avg. 127 m or 417 ft) |

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | |

Coullemelle is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

Coullemelle is situated on the D109 and D188 crossroads, some 19 miles (31 km) south of Amiens. It is located close to the Paris meridian at the edge of the Amiens plateau and of the Beauvaisis. Its territory, 954 hectares wide, is in contact with the lands of the neighboring villages of Grivesnes, Cantigny, Villers-Tournelle, Rocquencourt, Quiry-le-Sec and Esclainvillers. Its soil dates from the Tertiary. Under a layer of silt, one finds argillaceous chalk and flints. The plateau slopes gently to the north-east from 160 meters at a place called Le Crocq down to 120 meters in the Coullemelle and Grivesnes valleys. Located 80 kilometers from the sea, the village benefits from a temperate and healthy climate. At the North exit of the Coullemelle wood lies a larris, that is a zone of lawn and poor lands, most interesting for geologists and botanists. The dry valleys of Simie, Langueron, mont Foucart and Coullemelle, oriented N.E.-S.W., ties cuts through the chalky plateau that descends into the dry ravine occupied by trees but also by calcicole lawns.[1] One may find there lady orchids, fragrant orchids, red epacris, superb violet anemone that are exceptional in France, as well as very rare cruciate anemones.[2] The larris, unsuited to culture and which served as a pasture for sheep, are unfortunately more and more overgrown with underbrush.

History

Gallo-Roman period

The name Coullemelle comes from the Latin COLUMELLAE (small columns) which could designate boundary stones delimiting the territory of the village as suggested by places called to this day Les Bornes ("the boundary stones") and Les Hautes Bornes ("the high boundary stones") located on the frontiers of the neighboring communes of Rocquencourt and Villers-Tournelle. The Roman villas, the substructures of which were identified through aerial photographs[3] shot by Picard archaeologist Roger Agache demonstrate that the area was well exploited during the Gallo-Roman period. They were located between the chemin des Essertis ("the Essertis path") and the Grivesnes valley (average size villa, rectangular farmyard), at l’Epinette (wider villa, with a trapezoidal farmyard and with a legible central building), at the South-East exit of the village, between Pommeroy and le Moulin Prudent[4] · [5] ("the prudent mill"). Small substructures scattered over a large area on the South-East corner of the Coullemelle wood could be remains of a vicus (rural domain). The substructures were partly excavated. The vast majority of the inventoried furniture dates from the first centuries AD. The Neolithic left some traces in the site of l'Epinette ("the spruce"). Similarly, a small square enclosure spotted near le Bois Planté ("the planted wood") between Coullemelle and Grivesnes seems prehistoric.

Merovingian and Carolingian periods

The oldest discovered texts date from years 985 to 989.[6] They recall that every year on St. Mathieu fest, the twenty-four villages depending on the Corbie Abbey were to deliver two or four setiers of honey each and, for twenty-two of them, twenty-five to sixty muids of blackberries. CULMELLAE ou CUMELLAE was concerned by both annual debts. Moreover, the provost of the abbey Saint-Pierre of Corbie was responsible for organizing, at the expenses of the manse of Culmellae a past (annual festive meal) commemorating, every 9 September, Father Isaac. It is not proven that there was a special relationship between the recipient and the donor of the meal. Nineteen manses, seven of which were located in the current district of Montdidier, were to celebrate other abbots.[7] Isaac reigned from 840 to 843, thus his birthday pasts could have occurred after the middle of the ninth century. Queen Bathilde and her son Clotaire III had funded the Corbie Abbey in 657. Coullemelle lands were not part of the first dot, however, they were given to Corbie in the Merovingian or early Carolingian period.[8]

Demographic and economic development during the XIIth and the XIIIth centuries

In July 1209, Richard de Gerberoy, bishop of Amiens, founded the cure of Coullemelle (Colonmeles) from the dismembering of the Rocquencourt cure, at the request of Raoul de Clermont, of Foulque, Rocquencourt priest, of Osmond, Coullemelle vavasor and of the village inhabitants that were increasing in number.[9] To this cure was attached the mense of Lord Raoul, located in the Bois (forest), as well as the menses of Fourquivillers (Focolviller) and of Bus Oserain. Saint-Nicolas church was pre-existing the foundation of the cure. The benedictine prior d’Elincourt (in the Oise region) was the precentor. The « Focolviller » quoted in this text is the same as the « Forsenviller » of a chart of 1146 in which Thierry, bishop of Amiens, expresses the rights and the privileges of the benedictin priory of Notre-Dame of Montdidier and gives the list of its belongings such as portions of the forest and of the fields of Fourquivillers[10] · .[11] In a bull of 1173, Pope Alexander III confirmed the rights and the possessions of the priory. Osmond mayor had already to deal with the Corbie Abbey in 1174 when he had to recognize that his house in Coullemelle (Colomellis) with belonging to a fief of the abbey and that he owed the abey six capons and two setiers of vine [12] · .[13] He also owed the taxes of the Hopital, a lazaret located between Coullemelle, Villers-Tournelle and Rocquencourt. By compensation, the abbot of Corbie granted to Osmond the land of Fros under the express reserve to pay the "terrage" and the tithe to the abbey.

XIVth and XVth centuries, the Hundred Years' War and the Jacquerie

The war between the Plantagenets and the Valois for the throne of France is triggered by the death without heirs of Charles IV. The recovery by Philip VI of Valois of the Ponthieu from his English vassal caused devastation in East Picardy. After the French defeat at Crecy 1360, Ponthieu returned to England. Beauvaisis and Santerre are still controlled by the French, except during the 1429-1431 period when the Burgundians controlled northern Picardy and the English controlled southern Picardy. The English weaken and the war between Burgundy duke Philip the Good and French king Charles VII ends in 1435. However, the region remains disrupted until the late Middle Ages.

For Coullemelle and the nearby villages, the most important event is the Great Peasant Jacquerie in 1358,[14] soon after the defeat of Poitiers and the capture of John the Good by the English. Among the victims of the peasants are the brothers Raoul and Jean de Clermont-Nesle, lords of Coullemelle. On May the 28th, a convoy from the Montdidier region wants to cross the bridge of Saint-Leu-d'Esserent to deliver grains to the Parisians. The Clermont, who are on their land, opposed. Raoul was killed and his brother managed to escape. This is the beginning of an uprising against the nobility which extends in Beauvaisis, especially in the area of Montdidier. The Jacques loot and burn houses of Raoul and his mother in Fontaine and a mansion belonging to Jean in Courtemanche. Many other castles were destroyed by the Jacques, including those of Cardonnois, Mesnil St Firmin, the Herelle, Breteuil, Folleville, La Faloise, Lawarde-Mauger, Fransures, Louvrechy, Mailly-Raineval, Pierrepont and Moreuil, all less than fifteen kilometers from Coullemelle. The revolt was quickly suppressed. June the 10th, everything is over.

The Jacques were succeed, after a short respite, by big bands of adventurers who plunder and massacre between battles. The Breteuil Castle, destroyed by the English in 1427, is then occupied by captain Blanchefort, companion of La Hire and Joan of Arc, for Charles VII. His soldiers devastated villages among which, probably, Coullemelle.[15] The castle of Folleville passed from one hand to the other. During these troubled times, the lands become worthless. Charles VII fate winner of the war that ended in 1453.

In Coullemelle, the Busozerain farm and three hundred and eighty six journaux (about half a hectare) of land passes from the hands of the abbey of Visigneux to the Celestines of Offemont in 1395 then to the Amiens Celestines in 1435.

In 1488, the stronghold of the Bouteillerie, which includes two hundred journaux, belongs to François de Bourbon as husband of Mary of Luxembourg before being transmitted to John of Fransures in 1494. François is a descendant of Robert of France, sixth son of Saint Louis. Francis and Marie will have as great grandchildren both Henri IV and Mary Stuart. Marie's cousin John of Luxembourg St. Pol (1400-1466), Lord of Haubourdin and Ailly sur Noye whose church contains the monumental tomb where he is buried with his wife Jacqueline of Trémoille. John fought mainly for the Burgundians.

Throughout the war, the local population has decreased. In 1469, Rocquencourt has no more than twenty two fires, Quiry has twenty and Esclainvillers ten. The fifty fires of Coullemelle make it one of the most populated parishes of the provost of Montdidier.

Pierre Hurel from Colomelles, diocese of Amiens, appears in the register of the Masters of the University of Paris in 1349. The university was then divided into four Nations among which Picardy (fidelissima Picardorum natio) gather the students, speaking the same language, from ten dioceses from Laon and Beauvais to Utrecht and Liège. The other three nations were French, English and Norman.

XVIth century, from Charles XI to Henri IV

March 25, 1563, Charles IX ordered the alienation of the fourth part of the clergy property to support the kingdom. Accordingly, Corbie Abbey is obliged to sell part of its properties. The Fourquivillers farm with its two hundred and four journaux is awarded in September by Breteuil Abbey to Lanvin Geoffroy, abbot of Tenailles, Lord of Coullemelle, for three thousand six hundred and twenty six livres. Fourquivillers is then owned by Knights Jean Lanvin, brother of Geoffroy and Olivier Plessis, Lord of Blérancourt and Cuisabot. In 1583, cardinal Sainte-Croix, Abbot of Breteuil, gives the Fourquivillers farm to Antoine Estourmel, Lord of Plainville and Coullemelle. Four years later, Estourmel, who disputed the amount claimed by Breteuil he considers too high in view of the ravages of the soldiery, won his trial. Religious give up their claims and Estourmel pays them a hundred couronnes.[16]

Representatives of the three Estates are called in Peronne in 1567 to draw up the "practice of the government." Sir Geoffrey de Lanvin represents the Estate of nobility for his lands of Coullemelle and Fourquivillers.[17] The first Catholic League is formed there in 1568 headed by Jacques Humières, governor of Picardy, who refused to surrender the city to Protestants as requested by the king. Protestant lands are seized, particularly those of Folleville, Paillart and other lands owned by Louis de Lannoy.

August 3, 1588, the priest Jehan Frère part in the election of the representative of the clergy of the bailiwick of Montdidier to the Estates General of Blois. These Estates General sit on a background of struggles between factions of religious war (1562-1593), the Catholic League accusing the royal authority of complacency towards Protestants. The last forty years of the century were marked by these struggles. In Picardy, Protestantism is mainly a matter of nobles. It has the support of governors Coligny and Louis de Condé. The latter is a nephew of François de Vendôme-Bourbon and Marie de Luxembourg who had held the stronghold of the Bouteillerie between Coullemelle and Villers. He is lord of Breteuil from 1556 to 1569. The novelist Michel Peyramaure to praise the warrior skill of Henry IV, wrote that in 1592 he defeated by surprise the Spanish between Montdidier and Coullemelle[18] "The king was right. The Spanish army was in a hilly country. Farnese had spread its banners around the village of Coullemelle ". This happened in January when the king harassed the Spanish from Rouen to Folleville.

Coullemelle cultivates cereals and woad and has several grain and Waide (woad in Picard) mills on its territory. Grain farming is prosperous enough as opportunities to Flanders are wide open from the warehouses of Corbie. However, the market of waide, which was of great benefit, ends in jeopardy during the war. There remains as traces a place called "ch'moulin" (the mill) and the name of a family still living in the village "the Wadiers". It is the same for another place name: a farm located between Coullemelle, Villers-Tournelle and Rocquencourt that had belonged during the late sixteenth century to the Hospitallers of Saint John. The people of Rocquencourt still speak of this pasture of the "Hospital".

Population

| Year | 1910 | 1962 | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 305 | 249 | 270 | 213 | 215 | 230 | 236 | 238 |

| From the year 1962 on: No double counting—residents of multiple communes (e.g. students and military personnel) are counted only once. | ||||||||

Places of interest

St. Nicolas Church

The main monument of the village is the St. Nicolas Church. It was built after the First World War on the ruins of the old church destroyed in 1918 by the German artillery. The church has been consecrated Mg Lecomte in 1927. The outside is decorated by many corbels and the tympanum of the west portal is remarkable. Its registration in 1994 on the French Natural Heritage Site list (ISMH) was mainly motivated by its interior of Art deco style (more precisely, the so-called Art sacré d’entre-deux-guerres, [19] [20]). The overall harmony of the monument is due to its architects Pierre and Gérard Ansart[21] and the implementation by the craftsmen of the Groupement de Notre-Dame des Arts[22] is of remarkable quality. Altars, sculptures of simple geometric forms, long sgraffito mural with mosaic inlay, punctuate a beautiful Stations of the Cross. The mosaic of Saint Nicolas at the bottom of the apse, windows, furniture and metalwork, contribute to magnify the decor.

The memorial

The war memorial |

The monument, by architect Allard, is located on the central square in front of the school and of the town hall. It wears a large cross of Lorraine and, in low relief, two heads of helmeted soldiers symbolizing the two world wars. Left (first war) the head, surrounded by the names of the battles of Verdun and the Somme, wears an Adrian helmet. The head on the right (Second World War) has a helmet of armored car crew. It is surrounded by the names of the battles of Caen and Paris. The heads are topped with palms symbolizing the sacrifice. The monument was inaugurated in 1946. Below, on a plate, are engraved the names of fifteen soldiers died for France, eleven during the Great War and four in the second war. In addition there are names of three civilians.

Another monument commemorating World War I, is located at the center of the cemetery since 1925. The hexagonal base of the Calvary bears the names of ten people died for France. One face pays homage to "French and American soldiers killed in defense of Coullemelle in 1918."

Notable residents

- Don Etienne Carneau[23][24][25] (1610 - 1671), writer. Celestin, preacher, translator from Hebrew, Greek, Italian, Spanish, Latin and especially writer. He was born in Chartres in 1606. He entered the orders in 1630 and became the priest of Coullemelle in 1635. Famous author in his time,[26] he published poems, elegies, political songs, stanzas, songs, etc.. His main work is probably the stimmimachie [27] (1656), a long historicomic poem dedicated to Mazarin.[28] He was in charge of the cure of Coullemelle in 1639 when he wrote an Ode addressed to Bishop Faure, Bishop of Amiens on his first general synod.[29] He died in Paris in 1671.

- Lieutenant Cocu (1773 - 1845) soldier who served in all the campaigns of the Revolution and the Napoleonic campaigns. Soldier "of the Republic and the Empire," he participated in the combats of the 103rd Infantry Regiment for the duration of the Revolution and until 1814. He has 20 years in 1893, when military service became mandatory for a period of five years for singles of his age. For him, the military last 20 years. He joined the 103rd, build from the dislocation of the regiment of French Guards (where the famous D'Artagnan has served), which for centuries had been assigned to protect the king. He participated to the campaigns of Germany, Spain, France, Hainaut, Poland, Portugal, Prussia and Switzerland. So he fought, among others, in the battles of Austerlitz, Jena and Leipzig. Back to Coullemelle, Charles Cocu is inscribed in the tax list of years 1819-1821 as a teacher and surveyor. In 1821 it is "churchwarden of the parish factory" (member of the board responsible for the administration of the parish). Appointed treasurer, he resigned in 1826, judging himself as incompetent. At the cemetery, a monument in the shape of a truncated pyramid with carved flags, on a cubic base surrounded by four balusters, today near ruin, is engraved by the list of his military campaigns.

- Jean-François Dubois[30][31][32] (1821 - 1901), educator, administrator, writer, founder of the Quebec Commercial Academy. Born in a family of weavers from Coullemelle, called brother Aphraates, this father of the Christian Schools was sent to North America in 1843. He headed the Calvert Hall and founded, around 1857, the Rock Hill College in the state of Maryland then run a community and founded the Quebec Commercial Academy in 1862.[33] He published numerous textbooks in French and English.[34] He then served similar functions in England, Ireland, New York and finally in France as secretary of the General House in Paris.

- Baron Charles Tardieu de Saint Aubanet (1827 - 1902), Mayor of Coullemelle (1860-1876), naval officer and spy. Most romantic character of the village. Former naval officer, he rubbed shoulders, at commandant Rivière salon, with writers such as Alexandre Dumas. His military campaigns that had, among others, led him to the Middle East, where his ship was wrecked, and Morocco earned him admission to the National Order of the Legion of Honor.[35] He resigned from the army in 1864 and became a sort of country squire spending his time in its Amiens hotel and in the castle of Coullemelle, first owned by de la Roque his father in law. He was mayor of Coullemelle up to the beginning of the Republic which imposed him to resign for having celebrated in England the majority of the son of Napoleon the IIIrd.[36] Meanwhile, he was appointed colonel in 1869 at the Mobile National Guard [37] (battalion Montdidier who participated in the defense of Paris). He was then found in ministries for mysterious missions. He served as spy in England and Italy [38] and was the source of discord between Georges Clemenceau and Joseph Caillaux[39] in particular for his role at the England embassy.[40][41] He has published "Quelques réflexions sur le livre de l'Armée Française" (Considerations on the French Army white book [42] from General Niel) in 1867.

See also

References

- ↑ "ZNIEFF 220013965". Inventaire national du patrimoine Naturel (in French). Retrieved December the 31st, 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Bulletin de la Société linnéenne du nord de la France (in French). Retrieved December the 31st, 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "photographies aériennes". Ministère de la Culture (in French). Retrieved December the 24th, 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Agache, R. (1978). Somme préromaine et romaine d'après las prospections aériennes (in French). DRAC Amiens, rue Fuscien.

- ↑ Agache, R.; Bréard, B. (1975). Atlas (in French). DRAC Amiens, rue Fuscien.

- ↑ Appendix du polyptique de l’abbé Irminon (in French). Guérard. 1844.

- ↑ Morelle, L. (1991). La liste des repas commémoratifs, Revue Belge de philologie et d'histoire (in French).

- ↑ Levillain, L. Examen critique des chartes mérovingiennes et carolingiennes (in French).

- ↑ Archives de la Sommes, ed. (1209). manuscript on parchment, right hand side of a chirograph,3G350 (in French).

- ↑ Gallia Christiana, tome X (in French). p. 309.

- ↑ Victor de Beauvillé. Histoire de la ville de Montdidier, book III, chapter I (in French).

- ↑ Mémoires de la Société des Antiquaires de Picardie (MSAP) (in French). 1854. p. 405.

- ↑ cartulaire noir de Corbie F°129 (in French).

- ↑ Metzler, Annette (August the 11th 2012). "La Jacquerie à Saint Leu d'esserent". Héritage Lupovicien. Retrieved July the 24th 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ abbé Baticle, C.A. (1891). Nouvelle histoire de Breteuil (in French).

- ↑ série H, abbaye de Breteuil. Archives de l'Oise.

- ↑ Chauvelin; et al. (1724). Nouveau coutumier général (in French). 2. Paris: Michel Brunet.

- ↑ Peyramaure, Michel (2013). Henri IV (in French). Paris: Laffont.

- ↑ d'Agnel, Arnaud (1936). L'art religieux moderne (in French). Arthaud.

- ↑ L’art sacré entre les deux guerres : aspects de la Première Reconstruction en Picardie, In Situ, revue des patrimoines, accessed 15 August 2012

- ↑ Gérard Ansart, PatrimoinedeFrance.com, accessed 15 August 2012

- ↑ Ansart, G. (2002). Du trait et de la plume (in French). Bibliothèque Amiens-Métropole.

- ↑ "Etienne Carneau". Wikisource (in French). Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ↑ Michaud, J.Fr. Biographie Universelle Ancienne Et Moderne [Histoire] (in French). 7. HardPress Ltd.

- ↑ François, Jean. Bibliothèque Générale Des Ecrivains de L'Ordre de Saint Benoit (1777) (in French). Kessinger Publishing.

- ↑ Merlet, L. (2012). Poètes beaucerons antérieurs au XIXe siècle (in French). 1. Hachette Livre BNF. p. 318. ISBN 978-2012763142.

- ↑ La stimmimachie. Google books (in French). Retrieved August the 3rd, 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Carneau, E. Recueil des poèmes du Père Etienne Carneau (in French). Bibliothèque Mazarine (in 4°, n°20246).

- ↑ Carneau, curé de Coullemelle. Ode à Mgr. l'Evèque (in French). Bibliothèque d'Amiens (au catalogue).

- ↑ Hamelin, Jean; Cook, Ramsay (1994). Dictionary of Canadian Biography (1901-1910), article Bubois J.Fr. named Brother Aphraates. 13. University of Toronto Press. p. 1295. ISBN 978-0802039989.

- ↑ Dictionnaire biographique du Canada (1901-1910), article Bubois J.Fr. dit Frère Aphraates (in French). 13. University of Toronto Press, université Laval.

- ↑ Voisine, Nive (1987). Les frères des écoles chrétiennes au Canada (in French). A. Sigier. ISBN 978-2891290869.

- ↑ Lemire, Guy (May–June 2008). "L'Académie de Québec - un parcours glorieux". Reflets lasalliens (in French).

- ↑ "J.F.N.D.". Bibliothèque de l'université Laval (in French). Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ Bulletin des lois de la République Française (in French). 1860.

- ↑ Annales de l'Assemblée Nationale, compte rendu 1871-1942 (in French). 297 and following. 1875.

- ↑ Almanach Impérial (in French). 1870.

- ↑ Publicazione della Faculta de jurisprudenza, Storia des Trattate (in Italian). 1. Univ. Milano. 1967.

- ↑ Cailleaux, J. (1942). Mes Mémoires (in French). 1 (1865-1900). Plon, Paris.

- ↑ Paleologue, M. (1955). Journal de l'affaire Dreyfus (1894-99) (in French). Plon, Paris. ASIN B0017VI5C6.

- ↑ Green, Graham; Green, Hugh. The spy's bedside book. Bantam. ISBN 978-0099519607.

- ↑ Bon. de Saint-Aubanet (1867). Quelques réflexions sur le livre de l'Armée Française (in French). Impr. de E. Bruyère. p. 15. ASIN B001BSAB3Q.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coullemelle. |

- Coullemelle on the Quid website (French)