Missouri in the American Civil War

|

|

Union states in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Border states |

| Dual governments |

| Territories and D.C. |

|

|

Confederate States in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Border states |

| Dual governments |

| Territories |

In the American Civil War, Missouri was a border state that sent men, armies, generals, and supplies to both opposing sides, had its star on both flags, had separate governments representing each side, and endured a neighbor-against-neighbor intrastate war within the larger national war.

By the end of the Civil War Missouri had supplied nearly 110,000 troops to the Union and at least 30,000 troops for the Confederate Army and additional bands of pro–Confederate guerrillas.[1][2] There were battles and skirmishes in all areas of the state, from Iowa and the Illinois border in the northeast to the edge of the state in the southeast and southwest on the Arkansas border. Counting minor engagements, actions and skirmishes, Missouri saw over 1,200 distinct fights. Only Virginia and Tennessee exceeded Missouri in the number of clashes within the state's boundaries.

The first major Civil War battle west of the Mississippi River was on August 10, 1861 at Wilson's Creek, Missouri, while the largest battle west of the Mississippi River was the Battle of Westport at Kansas City in 1864.

Pre-war

Missouri Compromise

Missouri was initially settled by Southerners coming up the Mississippi River and Missouri River. Many brought a few slaves. Missouri entered the Union in 1821 as a slave state following the Missouri Compromise of 1820, in which Congress agreed that no other territory north of 36°30' (Missouri's southern border with Arkansas) could enter the Union as a slave state. Maine entered the Union as a free state in the compromise to balance Missouri.

Bleeding Kansas

One of the biggest concerns for Missouri slave-holders was a Federal law that decreed that if a slave physically entered a free state, the slave became free. The Underground Railroad, a system of safe houses, through which runaway slaves gained their freedom by heading north, was already established in the state. The slave owners were worried about the possibility of the entire western border becoming a conduit for the Underground Railroad, if those territories were made free states. In 1854 the Kansas–Nebraska Act nullified the Missouri Compromise and said the two states could choose to enter as a free or slave state. The result was a de facto war between pro-slavery residents of Missouri (called Border Ruffians) and Kansas Territories free staters to influence how Kansas entered the Union. Most conflicts involved attacks and murders of supporters of both sides, with the Sacking of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces and the Pottawatomie massacre by John Brown the most notable. Kansas initially approved a pro-slavery constitution called the Lecompton Constitution, but, after the U.S. Congress rejected it, the state approved a free-state Wyandotte Constitution.

Dred Scott Decision

Against the background of Bleeding Kansas, the case of Dred Scott, a slave who in 1846 sued in St. Louis, Missouri, for his freedom as he had been taken to a free state, reached the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1857 the Supreme Court ruled not only that slaves were not automatically made free simply by entering a free state, but more shockingly that no one of African ancestry could be considered a US citizen and thus had no standing. African-Americans could not initiate legal action in any court, even when they clearly had what would otherwise be a valid claim. The decision calmed the skirmishes between Missouri and Kansas partisans, but it enraged abolitionists and increased the vitriolic rhetoric that soon led to the Civil War.

Pony Express

With war storm clouds brewing in 1860, the government sought to communicate more quickly with San Francisco, California. In 1860 it took 25 days for a message to reach the coast from Missouri. The firm of Russell, Majors and Waddell proposed to do it in 10 days with a relay system of horses from what was then the furthest west terminus of a railroad at St. Joseph, Missouri. The resulting Pony Express began operations on April 3, 1860. Ulysses S. Grant's first commission in the Civil War was to protect the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad, which was delivering its mail.

Armed neutrality

By 1860, Missouri's initial southern settlers had been supplanted with a more diversified non-slave holding population, including former northerners, German and Irish immigrants. With war seeming inevitable, Missouri thought it could stay out of the conflict by remaining in the Union, but staying neutral—not giving men or supplies to either side and pledging to fight troops from either side who entered the state. The policy was first put forth in 1860 by outgoing Governor Robert Marcellus Stewart, who had Northern leanings. It was notionally reaffirmed by incoming Governor Claiborne Jackson, who had Southern leanings. Jackson however, stated in his inaugural address that in case of Federal "coercion" of southern states, Missouri should support and defend her "sister southern states". A Constitutional Convention to discuss secession was convened with Sterling Price presiding. The delegates voted to stay in the Union and supported the neutrality position.

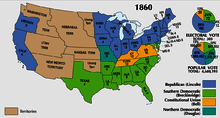

In the United States presidential election, 1860, Abraham Lincoln received only 10 percent of the state's votes, while 71 percent favored either John Bell or Stephen A. Douglas, both of whom wanted the status quo to remain (Douglas was to narrowly win the Missouri vote over Bell—the only state Douglas carried besides New Jersey) with the remaining 19 percent siding with Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge.

Missouri demographics in 1860

According to the 1860 U.S. Census, Missouri's total population was 1,182,012, of which 114,931 (9.7%) were slaves. Most of the slaves were in rural areas rather than cities.

Of the 299,701 responses to "Occupation", 124,989 listed "Farmers" and 39,396 listed "Farm Laborers." The next highest categories were "laborers" (30,668), "Blacksmith" (4,349), and Merchants (4,245).

Less than half the state was listed as native born (475,246, or 40%). Those coming from other states listed: Kentucky (99,814), Tennessee (73,504), Virginia (53,937), Ohio (35,380), Indiana (30,463), and Illinois (30,138), with lesser amounts from other states.

906,540 (77%) were listed as being born in the United States. Of the 160,541 foreign born, residents came from the German states (88,487), Ireland (43,481), England (10,009), France (5,283), and Switzerland (4,585), with lesser amounts from other countries.

|

Biggest Cities:

|

Biggest counties:

|

Most slaves:

|

Civil War

Conflicts and battles in the war were divided into three phases, starting with the Union removal of Governor Jackson and pursuit of Sterling Price and his Missouri State Guard in 1861; a period of neighbor-versus-neighbor bushwhacking guerrilla warfare from 1862 to 1864 (which actually continued long after the war had ended everywhere else, until at least 1889); and finally Sterling Price's attempt to retake the state in 1864.

During the war thousands of black refugees poured into St. Louis, where the Freedmen's Relief Society, the Ladies Union Aid Society, the Western Sanitary Commission, and the American Missionary Association (AMA) set up schools for their children.[4]

Missouri and the Election of 1860

In the election of 1860, Missouri's newly elected governor was Claiborne Fox Jackson, a career politician and an ardent supporter of the South. Jackson campaigned as a Douglas Democrat, favoring a conciliatory program on issues that divided the country. After Jackson's election, however, he immediately began working behind the scenes to promote Missouri's secession.[5] In addition to planning to seize the federal arsenal at St. Louis (see below), Jackson conspired with senior Missouri bankers to illegally divert money from the banks to arm state troops, a measure that the Missouri General Assembly had so far refused to take.[6]

Eviction of Governor Jackson

Camp Jackson Affair

Missouri's nominal neutrality was tested in a conflict over the St. Louis Arsenal. The Federal Government reinforced the Arsenal's tiny garrison with several detachments, most notably a force from the 2nd Infantry under Captain Nathaniel Lyon. The other federal arsenal in Missouri, Liberty Arsenal, had been captured on April 20 by secessionist militias and concerned by widespread reports that Governor Jackson intended to use the Missouri Volunteer Militia to also attack the Arsenal (and capture its 39,000 small arms), Secretary of War Simon Cameron ordered Lyon (by that time in acting command) to evacuate the majority of the munitions to Illinois. 21,000 guns were secretly evacuated to Alton, IL on the evening of April 29, 1861. At the same time, Governor Jackson called up the Missouri State Militia under Brig. Gen. Daniel M. Frost for maneuvers in suburban St. Louis at Camp Jackson. These maneuvers were perceived by Lyon as an attempt to seize the arsenal. On May 10, 1861, Lyon attacked the militia and paraded them as captives through the streets of St. Louis and a riot erupted. Lyon's troops, a Missouri militia mainly composed of German immigrants, opened fire on the attacking crowd killing 28 and injuring 100.

The next day, the Missouri General Assembly authorized the formation of a Missouri State Guard with Sterling Price as its commander to resist invasions from either side (but initially from the Union army). William S. Harney, Federal commander of the Department of the West, moved to quiet the situation by agreeing to the Missouri neutrality in the Price-Harney Truce. This led to pro-confederate sympathizers taking over most of Missouri, with pro-Unionist being harassed and forced to leave. Abraham Lincoln overruled the truce agreement and relieved Harney of command and replaced him with Lyon. On June 11, 1861, Lyon met with Governor Jackson and Missouri State Guard commander Major General Sterling Price at St. Louis' Planter's House hotel. The meeting, theoretically to discuss the possibility of continuing the Price-Harney Truce between U.S. and state forces, quickly deadlocked over basic issues of sovereignty and governmental power. Jackson and Price, who were working to construct the new Missouri State Guard in nine military districts statewide, wanted to contain the Federal toe-hold to the Unionist stronghold of St. Louis. Jackson demand that Federal forces be limited to the boundaries of St. Louis, and that pro-Unionist Missouri "Home Guards" in several Missouri town be disbanded. Lyon refused, and stated that if Jackson insisted on so limiting the power of the Federal Government "This means war". After Jackson was escorted from the lines, Lyon began a pursuit of Jackson and Price and his elected state government through the Battle of Boonville and Battle of Carthage (1861). Jackson and the pro-Confederate politicians fled to the southern part of the state. Jackson and a rump of the General Assembly eventually set up a government-in-exile in Neosho, Missouri and enacted an Ordinance of Secession. This government was recognized by the Confederacy, despite the fact that the "Act" was not endorsed by a plebiscite (as required by Missouri state law) and that Jackson's government was all but powerless inside Missouri.

Union provisional government

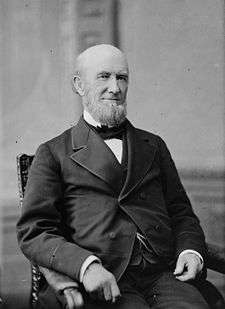

On July 22, 1861, following Lyon's capture of the Missouri capital at Jefferson City, the Missouri Constitutional Convention reconvened and declared the Missouri governor's office to be vacant. On July 28, it appointed former Missouri Supreme Court Chief Justice Hamilton Rowan Gamble as governor of the state and agreed to comply with Lincoln's demand for troops.

The provisional Missouri government began organizing new pro-Union regiments. Some like the 1st Missouri Volunteer Cavalry Regiment organized on September 6, 1861 would fight through the entire Civil War.[7] By the War's end, some 447 Missouri Regiments fought for the Union with many men serving in more than one of these.[8]

Battle of Wilson's Creek, Siege of Lexington, and Rebel Ascendancy

The biggest battle in the campaign to evict Jackson was the Battle of Wilson's Creek near Springfield, Missouri, on August 10, 1861. The battle marked the first time that the Missouri State Guard fought alongside Confederate forces. A combined force of over 12,000 Confederate soldiers, Arkansas State Troops, and Missouri State Guardsmen under Confederate Brigadier Ben McCulloch fought approximately 5,400 Federals in a punishing six hour battle. Union forces suffered over 1,300 casualties, including Lyon, who was fatally shot. The Confederates lost 1,200 men. The exhausted Confederates did not closely pursue the retreating Federals. In the aftermath of the battle, the southern commanders disagreed as to the proper next step. Price argued for an invasion of Missouri. McCulloch, concerned about security of Arkansas and Indian Territory, and skeptical about the possibility of subsisting his army in central Missouri, refused. The Confederate and Arkansas troops fell back to the border, while Price lead his Guardsmen into northwestern Missouri to recapture the state.

Price's emboldened Missouri State Guard marched on Lexington, besieging Col. Mulligan's garrison at the Siege of Lexington on September 12–20. Deploying wet hemp bales as mobile breastworks, the rebel advance was shielded from fire, including heated shot. By early afternoon of the 20th, the rolling fortification had advanced close enough for the Southerners to take the Union works in a final rush. By 2:00 p.m., Mulligan had surrendered. Price was reportedly so impressed by Mulligan's demeanor and conduct during and after the battle that he offered him his own horse and buggy, and ordered him safely escorted to Union lines. Years later, in his book The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, Southern president Jefferson Davis opined that "The expedient of the bales of hemp was a brilliant conception, not unlike that which made Tarik, the Saracen warrior, immortal, and gave his name to the northern pillar of Hercules."[9]

The hopes of many Southern-leaning, mostly farming-dependent, families, including Jesse James and family in Liberty, Mo., rose and fell based on news of Price's battles. "If Price succeeded, the entire state of Missouri might fall into the hands of the Confederacy. For all anyone knew, it would force Lincoln to accept the South's independence, in light of earlier rebel victories. After all, no one expected the war to last much longer."[10] The Siege and Battle of Lexington, also called the Battle of the Hemp Bales was a huge success for the rebels, and meant rebel ascendency, albeit temporarily, in Western and southwest Missouri. Combined with the loss of such a pivotal leader of the Federals' Western campaign in Nathaniel Lyon, and the Union's stunning defeat in the war's first major land battle, First Battle of Bull Run, Missouri's secessionists were "jubilant." Exaggerated stories and rumors of Confederate successes spread easily in this era of slower, often equine-based communication. St. Louis' (ironically named) Unionist-Democrat Daily Missouri Republican reported some of the secessionist scuttlebutt a week after the rebel victory at Lexington:

A party with whom I have conversed, says no one has any idea how much the secession cause has been strengthened since PRICE'S march to Lexington, and particularly since its surrender. The rebels are jubilant, and swear they will drive the Federalists into the Missouri and Mississippi before two months are over.A party of rebels recently stated that LINCOLN had been hanged by BEAUREGARD, and that for weeks past the National Congress had been held in Philadelphia.

Reports are rife in Western Missouri that the Southern Confederacy has been recognized by England and France, and that before the last of October the blockade will be broken by the navies of both nations. The rebels prophesy that before ten years have elapsed the Confederacy will be the greatest, most powerful, and prosperous, nation on the globe, and that the United States will decay, and be forced to seek the protection of England to prevent their being crushed by the South.[11]

Rebel ascendancy in Missouri was short-lived, however, as General John C. Frémont quickly mounted a campaign to retake Missouri. And "...without a single battle, the momentum suddenly shifted." On September 26, "Frémont moved west from St. Louis with thirty-eight thousand troops. Soon, he arrived at Sedalia, southeast of Lexington, threatening to trap the rebels against the river."[10] On September 29, Price was forced to abandon Lexington, and he and his men moved into southwest Missouri. "...their commanders do not wish to run any risk, their policy being to make attacks only where they feel confident, through superiority of numbers, of victory."[11] Price and his generals stuck firmly to this cautious strategy, and similar to General Joseph E. Johnston's retreat toward Atlanta, Price's Missouri State Guard fell back hundreds of miles in the face of a superior force. They soon retreated from the state and headed for Arkansas and later Mississippi.

Small remnants of the Missouri Guard remained in the state and fought isolated battles throughout the war. Price soon came under the command and control of the Confederates. In March 1862, any hopes for a new offensive in Missouri were dimmed in the Battle of Pea Ridge just south of the border in Arkansas. The Missouri State Guard was to stay largely intact as a unit through the war and was to suffer heavy casualties in Mississippi in the Battle of Iuka and Second Battle of Corinth.

Confederate Government of Missouri

In October 1861, the remnants of the elected state government that favored the South (including Jackson and Price) met in Neosho, and voted to formally secede from the Union. The measure gave them votes in the Confederate Congress, but otherwise was symbolic since they did not control any part of the state. The capital was to eventually move to Marshall, Texas. When Jackson died in office in 1862, his lieutenant governor, Thomas Caute Reynolds, succeeded him.

Frémont Emancipation

John C. Frémont replaced Lyon as commander of the Department of the West. Following the Wilson's Creek battle, he imposed martial law on the state and issued an order freeing the slaves of Missourians who were in rebellion.

The property, real and personal, of all persons in the State of Missouri who shall take up arms against the United States, and who shall be directly proven to have taken active part with their enemies in the field, is declared to be confiscated to the public use; and their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared free.[12]

This was not a general emancipation in the state as it did not extend to slaves owned by citizens who remained loyal. It did, however, exceed the Confiscation Act of 1861 which only allowed the United States to claim ownership of the slave if the slave was proven to "work or to be employed in or upon any fort, navy-yard, dock, armory, ship, entrenchment, or in any military or naval service whatsoever, against the Government and lawful authority of the United States."[12] Lincoln, fearing the emancipation would enrage neutral Missourians and slave states in Union control, granted Governor Gamble's request to rescind the emancipation and ease martial law.

Ironclad Navy and Riverine Campaigns

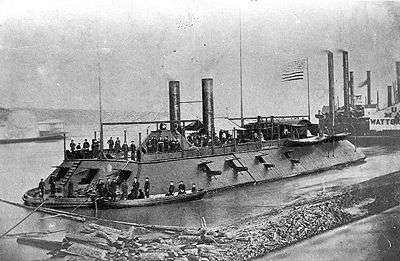

While various forces battled inconclusively for southwest Missouri, a unique Army-Navy-civilian cooperative effort built a war winning riverine navy. St. Louis river salvage expert, and engineering genius, James Buchanan Eads[13] won a contract to build a fleet of shallow-draft ironclads for use on the western rivers. An unusually cooperative relationship between Army officials (who would own the vessels) and Navy officers (who would command them) helped speed the work. Drawing on his reputation and personal credit (and that of St. Louis Unionists) Eads used subcontractors throughout the midwest (and as far east as Pittsburg) to produce nine ironclads in just over three months. Built at Eads' own Union Marine Works (in the St. Louis suburb of Carondelet), and at a satellite yard at Cairo, Illinois, the seven City-class ironclads,[14] the Essex, and heavy ironclad Benton were the first U.S. ironclads and the first to see combat.

St. Louis' Benton Barracks became the mustering depot for western troops, and in February 1862, Department of Missouri commander Major General Henry Halleck approved a joint invasion of west Tennessee along the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. Army troops under Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant and the newly built Western Gunboat Flotilla, commanded by Navy Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote, captured Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, unhinging the Confederate defensive perimeter in the west. After the subsequent Battle of Shiloh, the Federal Army pushed into northern Mississippi, while the Gunboat fleet moved down the Mississippi with cooperating Federal troops, systematically capturing every Confederate position north of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

The riverine strategy put the Confederacy on the defensive in the west for the rest of the war, and effectively ended meaningful Confederate efforts to recapture Missouri. The defeat of a Confederate army in northern Arkansas, at the Battle of Pea Ridge, further discouraged the Confederate leadership as to the wisdom, or possibility, of occupying Missouri. Subsequent military Confederate military action in the state would be limited to a small number of large raids (notably Shelby's Raid of 1863 and Price's Raid of 1864), and partial endorsement of the activities of Missouri guerrillas.

Western Sanitary Commission

The Western Sanitary Commission was a private agency based in St. Louis that was a rival of the larger U.S. Sanitary Commission. It operated during the war to help the U.S. Army deal with sick and wounded soldiers. It was led by abolitionists and especially after the war focused more on the needs of Freedmen. It was founded in August 1861, under the leadership of Reverend William Greenleaf Eliot (d. 1886), to care for the wounded soldiers after the opening battles. It was supported by private fundraising in the city of St. Louis, as well as from donors in California and New England. Parrish explains it selected nurses, provided hospital supplies, set up several hospitals, and outfitted several hospital ships. It also provided clothing and places to stay for freedmen and refugees, and set up schools for black children. It continued to finance various philanthropic projects until 1886.[15][16]

Guerrilla warfare

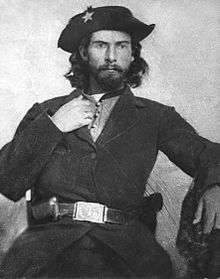

The Battle of Wilson's Creek was the last large scale engagement in the state until Price returned in 1864 in a last-ditch attempt to capture the state. Between 1862 and 1864 the state endured guerrilla warfare in which southern partisan rangers and Bushwhackers battled the Kansas irregulars known as Jayhawkers and Redlegs or "Redleggers" (from the red gaiters they wore around their lower legs) and the allied Union forces.

Jayhawker raids against perceived civilian "Confederate sympathizers" alienated Missourians and made maintaining the peace even harder for the Unionist provisional government. As Major General Henry Halleck wrote General John C. Frémont in September 1861, [Jayhawker raider] Jim Hale had to be removed from the Kansas border as "A few more such raids" would render Missouri "as unanimous against us as is Eastern Virginia."[17] While Jayhawker violence alienated communities who would have otherwise been loyal supporters of the Union, marauding bands of pro-secession bushwhackers sustained guerrilla war and outright banditry, especially in Missouri's northern counties. Major General John Pope, who oversaw northern Missouri, blamed local citizens for not doing enough to put down bushwhacker guerrillas and ordered locals to raise militias to counter them. "Refusal to do so would bring an occupying force of federal soldiers into their counties."[17] Pope, Ewing and Frémont's heavy-handed approach alienated even those civilians who were suffering at the hands of the bushwhackers.

Although guerrilla warfare occurred throughout much of the state, most of the incidents occurred in northern Missouri and were characterized by ambushes of individuals or families in rural areas. These incidents were particularly nefarious because their vigilante nature was outside the command and control of either side and often pitted neighbor against neighbor. Civilians on all sides faced looting, violence and other depredations.

Among the more notorious incidents of guerrilla warfare were the Sacking of Osceola, burning of Platte City and the Centralia Massacre. Among the famous bushwhackers were Quantrill's Raiders and Bloody Bill Anderson.

General Order No. 11

In 1863 following the Lawrence Massacre in Kansas, Union General Thomas Ewing, Jr. accused farmers in rural Missouri of either instigating the attack or supporting it. He issued General Order No. 11 which forced the evacuation of all residents of rural areas of the four counties (Jackson, Cass, Bates and Vernon) south of the Missouri River on the Kansas border to leave their property, which was then burned. The order applied to farmers regardless of loyalty, although those who could prove their loyalty to the Union could stay in designated towns and those who could not were exiled entirely. Among those forced to leave were Kansas City founder John Calvin McCoy and its first mayor, William S. Gregory.

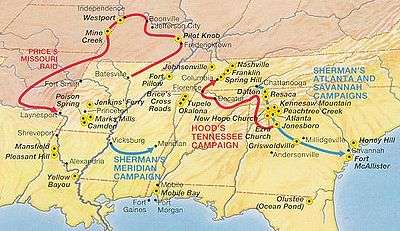

Price's Raid

With the Confederacy clearly losing the war in 1864, Sterling Price reassembled his Missouri Guard and launched a last gasp offensive to take Missouri. However, Price was unable to repeat his 1861 victorious campaigns in the state. Striking in the southeastern portion of the state, Price moved north, and attempted to capture Fort Davidson but failed. Next, Price sought to attack St. Louis but found it too heavily fortified and thus broke west in a parallel course with the Missouri River. This took him through the (relatively) friendly country of the "Boonslick", which had provided a large percentage of the Missouri volunteers who had joined the CSA. Ironically, although Price had issued orders against pillage, many of the pro-Confederate civilians in this area (which would be known as "Little Dixie" after the war) suffered from looting and depredations at the hands of Price's men.[18]

The Federals attempted to retard Price's advance through both minor and substantial skirmishing such as at Glasgow and Lexington. Price made his way to the extreme western portion of the state, taking part in a series of bitter battles at the Little Blue, Independence, and Byram's Ford. His Missouri campaign culminated in the battle of Westport in which over 30,000 troops fought, leading to the defeat of the Southern army. The Missourians retreated through Kansas and Indian Territory into Arkansas, where they stayed for the remainder of the war.

Reconstruction

Since Missouri had remained in the Union, it did not suffer outside military occupation or other extreme aspects of Reconstruction. The immediate post-war state government was controlled by Republicans, who attempted to execute an "internal reconstruction", banning politically powerful former secessionists from the political process and empowering the state's newly emancipated African-American population. This led to major dissatisfaction among many politically important groups, and provided opportunities for reactionary elements in the state.

The Democrats were to return to being the dominant power in the state by 1873 through an alliance with returned ex-Confederates (almost all of whom had been part of the pro-slavery Anti-Benton wing of the Missouri Democratic Party prior to the Civil War). The reunified Democratic Party exploited themes of: racial prejudice version of a Missouri "Lost Cause" which purported Missourians as victims of Federal tyranny and outrages; and depiction of Missouri Unionists and Republicans as traitors (to the state) and criminals. This capture of the historical narrative was largely successful, and secured control of the state for the Democratic Party through the 1950s. The ex-Confederate/Democratic resurgence also defeated efforts to empower Missouri's African-American population, and ushered in the state's version of Jim Crow legislation. (This was motivated both by widespread racial prejudice and concerns that former slaves were likely to be reliable Republican voters.)

Many newspapers in the 1870s Missouri were vehement in their opposition to national Radical Republican policies, for political, economic, and racial reasons. The outlaws James-Younger gang was to capitalize on this and become folk heroes as they robbed banks and trains while getting sympathetic press from the state's newspapers—most notably the Kansas City Times under founder John Newman Edwards. Jesse James, who killed with bushwacker Bloody Bill Anderson at Centralia, was to excuse his murder of a resident of Gallatin, during a bank robbery, saying he thought he was killing Samuel P. Cox, who had hunted down Anderson after Centralia. In addition, the vigilante activities of the 'Bald Knobbers' in south-central Missouri during the 1880s have been interpreted by some as a further continuation of Civil War related guerrilla warfare.[19]

See also

- Confederate States of America - animated map of state secession and confederacy

- List of Missouri Confederate Civil War units

- Missouri State Guard

- List of Missouri Union Civil War units

References and notes

- ↑ Missouri Secretary of State, "Abstract of Wars & Military Engagements: War of 1812 through World War I"

- ↑ Missouri Civil War Museum

- ↑ Fulton, by far the current largest city was not listed in the printed list. Other cities/towns in Callaway were Bourbon (1,689); Cedar (1,639); Catesausdlsein (1,993); Liberty (1,448); Round Prairie (955).

- ↑ Lawrence O. Christensen, "Black Education in Civil War St. Louis," Missouri Historical Review, April 2001, Vol. 95 Issue 3, pp 302-316

- ↑ Phillips, Christopher. Missouri's Confederate: Claiborne Fox Jackson and the Creation of Southern Identity in the Border West. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-8262-1272-6. pp. 238-239

- ↑ Geiger, Mark W. Financial Fraud and Guerrilla Violence in Missouri's Civil War, 1861-1865. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-300-15151-0. "Introduction"

- ↑ Missouri Digital Heritage (2007). "1St REGIMENT CAVALRY VOLUNTEERS". Missouri Office of the Secretary of State • Missouri State Library • Missouri State Archives • The State Historical Society of Missouri. Retrieved July 12, 2015. NOTE: These records also refer to the National Archives and Records Administration; Carded Records Showing Military Service of Soldiers Who Fought in Volunteer Organizations During the American Civil War, compiled 1890 - 1912, documenting the period 1861 - 1866; Catalog ID: 300398; Record Group #: 94; Roll #: 724.

- ↑ "Civil War Archives - Missouri - Union Regimental Index". Civil War Archives. 2009. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ↑ Davis, Jefferson, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. Publication date unknown, pg. 432. Retrieved on July 27, 2008.

- 1 2 Stiles, T. J. (2003). Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. Westminster, MD, USA: Knopf Publishing Group. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-375-70558-8.

- 1 2 J. H. B. (September 27, 1861). "From Jefferson City: Special Dispatch to the Republican". Daily Missouri Republican, Daily Evening Edition. Saint Louis, Mo.: State Historical Society of Missouri; Columbia, MO. p. 1. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- 1 2 "The Beginning of the End". Harper's Weekly, Sept. 14, 1861. 2nd paragraph.

- ↑ Eads is considered to be one exceptional engineers of the 19th Century. He became a millionaire before the war salvaging river wrecks and cargoes with a fleet of specially designed salvage vessels and a diving bell. During the war he built four generation of ironclad's, the last of which left the river, joined the Federal fleet and participated in the attack on Mobile Bay. After the war he built the revolutionary steel arch bridge at St. Louis and designed the river control system for the mouth of the Mississippi. The American Association of Civil Engineers memorialized Eads with a tablet honoring him in the Colonnade of the Hall of Fame at New York University, and he was the first American to be awarded the prestigious Albert Medal by the British Royal Society of Arts.

- ↑ The City-class ironclads were named after river cities and towns: Cairo, Carondelet, Cincinnati, Louisville, Mound City, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis. They were initially commissioned by the War Department (Army) rather than the Navy, and even after transfer to Navy control were referred to as "U.S. Gunboat" rather than "United State Ship" (U.S.S.) in official correspondence. (In subsequent official U.S. Navy history however, they are referred to as "U.S.S." and considered commissioned warships and part of fleet lineage.) When the river fleet was transferred to the Navy in autumn of 1862, the U.S. Gunboat St. Louis was renamed Baron DeKalb, there already being a sloop of war named St. Louis in naval service.

- ↑ William E. Parrish, "The Western Sanitary Commission," Civil War History, March 1990, Vol. 36 Issue 1, pp 17–35

- ↑ W.S. Rosecrans, "Annual Report of the Western Sanitary Commission for the Years Ending July, 1862, and July, 1863"; "Circular of Mississippi Valley Sanitary Fair, to Be Held in St. Louis, May 17th, 1864" The North American Review, Vol. 98, No. 203 (Apr., 1864), pp. 519-530 in JSTOR

- 1 2 Siddali, Silvana (2009). Missouri's War: The Civil War in Documents. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8214-4335-4.

- ↑ After Price's return south, the issue of looting and murder during "independent scouting" would become a major embarrassment during the court martial inquest into the failure of Price's Raid. Price's officers blamed these bad actions on the low quality of some of the men who composed Price's force.

- ↑ The political orientation of post-war "armed resistance" was different in the rugged south central part of the state. In this case, notionally pro-Union "Bald Knobbers" were (supposedly) resisting the political resurgence of formerly pro-secessionist "anti-Bald Knobbers". This violence may have had more to do with struggles for local power by group and family alliances, that with war-time politics.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Galusha. The Story of a Border City During the Civil War (1908) online.

- Astor, Aaron. Rebels on the Border: Civil War, Emancipation, and the Reconstruction of Kentucky and Missouri (LSU Press; 2012) 360 pp

- Boman, Dennis K. "All Politics Are Local: Emancipation in Missouri," in Lincoln Emancipated: The President and the Politics of Race, ed. Brian R. Dirck, pp 130–54. (Northern Illinois University Press, 2007)

- Boman, Dennis K. Lincoln's Resolute Unionist: Hamilton Gamble, Dred Scott Dissenter and Missouri's Civil War Governor (Louisiana State University Press, 2006) 263 pp.

- Fellman, Michael. Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri during the American Civil War (1989).

- Fitzsimmons, Margaret Louise. "Missouri Railroads During the Civil War and Reconstruction." Missouri Historical Review 35#2 (1941) pp. 188–206

- Geiger, Mark W. Financial Fraud and Guerrilla Violence in Missouri's Civil War, 1861–1865. (Yale University Press, 2010) (ISBN 9780300151510)

- Hess, Earl J. "The 12th Missouri Infantry: A Socio-Military Profile of a Union Regiment," Missouri Historical Review (October 1981) 76#1 pp 53–77.

- Kamphoefner, Walter D., "Missouri Germans and the Cause of Union and Freedom," Missouri Historical Review, 106#2 (April 2012), 115-36.

- Lause, Mark A. Price's Lost Campaign: The 1864 Invasion of Missouri (University of Missouri Press; 2011), 288 pages

- McGhee, James E. Guide to Missouri Confederate Units, 1861-1865 (University of Arkansas Press, 2008) 296 pp.

- March, David D. "Charles D. Drake and the Constitutional Convention of 1865." Missouri Historical Review 47 (1953): 110-123.

- Nichols, Bruce. Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri, 1862 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004) 256 pp. ISBN 0-7864-1689-0

- Parrish, William E. A History of Missouri, Volume III: 1860 to 1875 (1973, reprinted 2002) (ISBN 0-8262-0148-2); the standard scholarly history

- Phillips, Christopher. Missouri's Confederate: Claiborne Fox Jackson and the Creation of Southern Identity in the Border West (U of Missouri Press, 2000) (ISBN 978-0-8262-1272-6)

- Potter, Marguerite. "Hamilton R. Gamble, Missouri's War Governor." Missouri Historical Review 35#1 (1940): 25-72

- Saeger, Andrew M. "The Kingdom Of Callaway: Callaway County, Missouri during the Civil War." (MA thesis, Northwest Missouri State University, 2013). bibliography pp 75–81 online

- Stith, Matthew M. "At the Heart of Total War: Guerrillas, Civilians, and the Union Response in Jasper County, Missouri, 1861-1865," Military History of the West 38#1 (2008), 1-27.

Primary sources

- Siddali, Silvana R., ed. Missouri's War: The Civil War in Documents (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2009) 274 pp.

See also

- St. Louis in the Civil War

- List of Missouri Civil War Units

- Missouri Civil War Confederate Units

- List of battles fought in Missouri

External links

- Divided State: Missouri Military Organizations in the Civil War

- Missouri Civil War Battles, Skirmishes, & Engagements

- Missouri Civil War Union Militia Organizations

- Missouri in the Civil War

- National Park Service map of Civil War sites in Missouri

- The Civil War in Missouri: a Selected, Annotated Bibliography

- The Civil War, Slavery and Reconstruction in Missouri

- Official Missouri State Civil War Site

- American Civil War Research Database Status

- A Few Fascinating Missouri Civil War Facts