Harmonic mean

In mathematics, the harmonic mean (sometimes called the subcontrary mean) is one of several kinds of average, and in particular one of the Pythagorean means. Typically, it is appropriate for situations when the average of rates is desired. The harmonic mean can be expressed as the reciprocal of the arithmetic mean of the reciprocals. As a simple example, the harmonic mean of 1, 2, and 4 is

Definition

The harmonic mean H of the positive real numbers is defined to be

The third formula in the above equation expresses the harmonic mean as the reciprocal of the arithmetic mean of the reciprocals.

From the following formula:

it is more apparent that the harmonic mean is related to the arithmetic and geometric means. It is the reciprocal dual of the arithmetic mean for positive inputs:

The harmonic mean is a Schur-concave function, and dominated by the minimum of its arguments, in the sense that for any positive set of arguments, . Thus, the harmonic mean cannot be made arbitrarily large by changing some values to bigger ones (while having at least one value unchanged).

Relationship with other means

The harmonic mean is one of the three Pythagorean means. For all positive data sets containing at least one pair of nonequal values, the harmonic mean is always the least of the three means,[1] while the arithmetic mean is always the greatest of the three and the geometric mean is always in between. (If all values in a nonempty dataset are equal, the three means are always equal to one another; e.g., the harmonic, geometric, and arithmetic means of {2, 2, 2} are all 2.)

It is the special case M−1 of the power mean:

Since the harmonic mean of a list of numbers tends strongly toward the least elements of the list, it tends (compared to the arithmetic mean) to mitigate the impact of large outliers and aggravate the impact of small ones.

The arithmetic mean is often mistakenly used in places calling for the harmonic mean.[2] In the speed example below for instance, the arithmetic mean of 50 is incorrect, and too big.

The harmonic mean is related to the other Pythagorean means, as seen in the third formula in the above equation. This can be seen by interpreting the denominator to be the arithmetic mean of the product of numbers n times but each time omitting the j-th term. That is, for the first term, we multiply all n numbers except the first; for the second, we multiply all n numbers except the second; and so on. The numerator, excluding the n, which goes with the arithmetic mean, is the geometric mean to the power n. Thus the nth harmonic mean is related to the nth geometric and arithmetic means. The general formula is

If a set of non-identical numbers is subjected to a mean-preserving spread — that is, two or more elements of the set are "spread apart" from each other while leaving the arithmetic mean unchanged — then the harmonic mean always decreases.[3]

Harmonic mean of two or three numbers

Two numbers

For the special case of just two numbers, and , the harmonic mean can be written

In this special case, the harmonic mean is related to the arithmetic mean and the geometric mean by

Since by the inequality of arithmetic and geometric means, this shows for the n = 2 case that H ≤ G (a property that in fact holds for all n). It also follows that , meaning the two numbers' geometric mean equals the geometric mean of their arithmetic and harmonic means.

Three numbers

Three positive numbers H, G, and A are respectively the harmonic, geometric, and arithmetic means of three positive numbers if and only if[4]:p.74,#1834

Weighted harmonic mean

If a set of weights , ..., is associated to the dataset , ..., , the weighted harmonic mean is defined by

The unweighted harmonic mean can be regarded as the special case where all of the weights are equal.

Examples

In physics

In certain situations, especially many situations involving rates and ratios, the harmonic mean provides the truest average. For instance, if a vehicle travels a certain distance at a speed x (e.g., 60 kilometres per hour - km/h) and then the same distance again at a speed y (e.g., 40 km/h), then its average speed is the harmonic mean of x and y (48 km/h), and its total travel time is the same as if it had traveled the whole distance at that average speed. However, if the vehicle travels for a certain amount of time at a speed x and then the same amount of time at a speed y, then its average speed is the arithmetic mean of x and y, which in the above example is 50 kilometres per hour. The same principle applies to more than two segments: given a series of sub-trips at different speeds, if each sub-trip covers the same distance, then the average speed is the harmonic mean of all the sub-trip speeds; and if each sub-trip takes the same amount of time, then the average speed is the arithmetic mean of all the sub-trip speeds. (If neither is the case, then a weighted harmonic mean or weighted arithmetic mean is needed. For the arithmetic mean, the speed of each portion of the trip is weighted by the duration of that portion, while for the harmonic mean, the corresponding weight is the distance. In both cases, the resulting formula reduces to dividing the total distance by the total time.)

However one may avoid use of the harmonic mean for the case of "weighting by distance". Pose the problem as finding "slowness" of the trip where "slowness" (in hours per kilometre) is the inverse of speed. When trip slowness is found, invert it so as to find the "true" average trip speed. For each trip segment i, the slowness si=1/speedi. Then take the weighted arithmetic mean of the si's weighted by their respective distances (optionally with the weights normalized so they sum to 1 by dividing them by trip length). This gives the true average slowness (in time per kilometre). It turns out that this procedure, which can be done with no knowledge of the harmonic mean, amounts to the same mathematical operations as one would use in solving this problem by using the harmonic mean. Thus it illustrates why the harmonic mean works in this case.

Similarly, if one wishes to estimate the density of an alloy given the densities of its constituent elements and their mass fractions (or, equivalently, percentages by mass), then the predicted density of the alloy (exclusive of typically minor volume changes due to atom packing effects) is the weighted harmonic mean of the individual densities, weighted by mass, rather than the weighted arithmetic mean as one might at first expect. To use the weighted arithmetic mean, the densities would have to be weighted by volume. Applying dimensional analysis to the problem, while labeling the mass units by element and making sure that only like element-masses cancel, makes this clear.

If one connects two electrical resistors in parallel, one having resistance x (e.g., 60 Ω) and one having resistance y (e.g., 40 Ω), then the effect is the same as if one had used two resistors with the same resistance, both equal to the harmonic mean of x and y (48 Ω): the equivalent resistance in either case is 24 Ω (one-half of the harmonic mean). However, if one connects the resistors in series, then the average resistance is the arithmetic mean of x and y (with total resistance equal to the sum of x and y). And, as with the previous example, the same principle applies when more than two resistors are connected, provided that all are in parallel or all are in series.

The same principle applies to capacitors in series.

The "conductivity effective mass" of a semiconductor is also defined as the harmonic mean of the effective masses along the three crystallographic directions.[5]

In finance

The weighted harmonic mean is the preferable method for averaging multiples, such as the price–earnings ratio (P/E), in which price is in the numerator. If these ratios are averaged using a weighted arithmetic mean (a common error), high data points are given greater weights than low data points. The weighted harmonic mean, on the other hand, gives equal weight to each data point.[6] The simple weighted arithmetic mean when applied to non-price normalized ratios such as the P/E is biased upwards and cannot be numerically justified, since it is based on equalized earnings; just as vehicles speeds cannot be averaged for a roundtrip journey.[7]

For example, consider two firms, one with a market capitalization of $150 billion and earnings of $5 billion (P/E of 30) and one with a market capitalization of $1 billion and earnings of $1 million (P/E of 1000). Consider an index made of the two stocks, with 30% invested in the first and 70% invested in the second. We want to calculate the P/E ratio of this index.

Using the weighted arithmetic mean (incorrect):

Using the weighted harmonic mean (correct):

Thus, the correct P/E of 93.46 of this index can only be found using the weighted harmonic mean, while the weighted arithmetic mean will significantly overestimate it.

In geometry

In any triangle, the radius of the incircle is one-third of the harmonic mean of the altitudes.

For any point P on the minor arc BC of the circumcircle of an equilateral triangle ABC, with distances q and t from B and C respectively, and with the intersection of PA and BC being at a distance y from point P, we have that y is half the harmonic mean of q and t.[8]

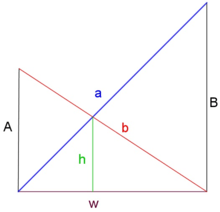

In a right triangle with legs a and b and altitude h from the hypotenuse to the right angle, h² is half the harmonic mean of a² and b².[9][10]

Let t and s (t > s) be the sides of the two inscribed squares in a right triangle with hypotenuse c. Then s² equals half the harmonic mean of c² and t².

Let a trapezoid have vertices A, B, C, and D in sequence and have parallel sides AB and CD. Let E be the intersection of the diagonals, and let F be on side DA and G be on side BC such that FEG is parallel to AB and CD. Then FG is the harmonic mean of AB and DC. (This is provable using similar triangles.)

In the crossed ladders problem, two ladders lie oppositely across an alley, each with feet at the base of one sidewall, with one leaning against a wall at height A and the other leaning against the opposite wall at height B, as shown. The ladders cross at a height of h above the alley floor. Then h is half the harmonic mean of A and B. This result still holds if the walls are slanted but still parallel and the "heights" A, B, and h are measured as distances from the floor along lines parallel to the walls.

In an ellipse, the semi-latus rectum (the distance from a focus to the ellipse along a line parallel to the minor axis) is the harmonic mean of the maximum and minimum distances of the ellipse from a focus.

In other sciences

In computer science, specifically information retrieval and machine learning, the harmonic mean of the precision (true positives per predicted positive) and the recall (true positives per real positive) is often used as an aggregated performance score for the evaluation of algorithms and systems: the F-score (or F-measure). This is used in information retrieval because only the positive class is of relevance and number of negatives is not in general known. It is thus a trade-off as to whether the correct positive predictions should be measured in relation to the number of predicted positives or the number of real positives, so it is measured versus a putative number of positives that is an arithmetic mean of the two possible denominators.

An interesting consequence arises from basic algebra in problems where people or systems work together. As an example, if a gas-powered pump can drain a pool in 4 hours and a battery-powered pump can drain the same pool in 6 hours, then it will take both pumps 6·4/6+4, which is equal to 2.4 hours, to drain the pool together. Interestingly, this is one-half of the harmonic mean of 6 and 4: 2·6·4/6+4 = 4.8. That is the appropriate average for the two types of pump is the harmonic mean, and with one pair of pumps (two pumps) it takes half this harmonic mean time, while with two pairs of pumps (four pumps) it would take a quarter of this harmonic mean time.

In electronics the harmonic mean in the same way gives the average contribution per component for parallel resistance, parallel inductance, serial conductance and serial capacitance.

In hydrology, the harmonic mean is similarly used to average hydraulic conductivity values for flow that is perpendicular to layers (e.g., geologic or soil) - flow parallel to layers uses the arithmetic mean. This apparent difference in averaging is explained by the fact that hydrology uses conductivity, which is the inverse of resistivity.

In sabermetrics, a player's Power–speed number is the harmonic mean of their home run and stolen base totals.

In population genetics, the harmonic mean is used when calculating the effects of fluctuations in generation size on the effective breeding population. This is to take into account the fact that a very small generation is effectively like a bottleneck and means that a very small number of individuals are contributing disproportionately to the gene pool, which can result in higher levels of inbreeding.

When considering fuel economy in automobiles two measures are commonly used – miles per gallon (mpg), and litres per 100 km. As the dimensions of these quantities are the inverse of each other (one is distance per volume, the other volume per distance) when taking the mean value of the fuel-economy of a range of cars one measure will produce the harmonic mean of the other – i.e., converting the mean value of fuel economy expressed in litres per 100 km to miles per gallon will produce the harmonic mean of the fuel economy expressed in miles-per-gallon.

In chemistry and nuclear physics the average mass per particle of a mixture consisting of different species (e.g., molecules or isotopes) is given by the harmonic mean of the individual species' masses weighted by their respective mass fraction.

See also

References

- ↑ Da-Feng Xia, Sen-Lin Xu, and Feng Qi, "A proof of the arithmetic mean-geometric mean-harmonic mean inequalities", RGMIA Research Report Collection, vol. 2, no. 1, 1999, http://ajmaa.org/RGMIA/papers/v2n1/v2n1-10.pdf

- ↑

- Statistical Analysis, Ya-lun Chou, Holt International, 1969, ISBN 0030730953

- ↑ Mitchell, Douglas W., "More on spreads and non-arithmetic means," The Mathematical Gazette 88, March 2004, 142-144.

- ↑ Inequalities proposed in “Crux Mathematicorum”, .

- ↑ http://ecee.colorado.edu/~bart/book/effmass.htm

- ↑ "Fairness Opinions: Common Errors and Omissions". The Handbook of Business Valuation and Intellectual Property Analysis. McGraw Hill. 2004. ISBN 0-07-142967-0.

- ↑ Agrrawal, Pankaj; Borgman, Richard; Clark, John M.; Strong, Robert (2010). "Using the Price-to-Earnings Harmonic Mean to Improve Firm Valuation Estimates". Journal of Financial Education. 36 (3–4): 98–110. JSTOR 41948650. SSRN 2621087

.

. - ↑ Posamentier, Alfred S.; Salkind, Charles T. (1996). Challenging Problems in Geometry (Second ed.). Dover. p. 172. ISBN 0-486-69154-3.

- ↑ Voles, Roger, "Integer solutions of ," Mathematical Gazette 83, July 1999, 269–271.

- ↑ Richinick, Jennifer, "The upside-down Pythagorean Theorem," Mathematical Gazette 92, July 2008, 313–;317.