Hydropower

.jpg)

| Part of a series on |

| Renewable energy |

|---|

Hydropower or water power (from the Greek: ύδωρ, "water") is power derived from the energy of falling water or fast running water, which may be harnessed for useful purposes. Since ancient times, hydropower from many kinds of watermills has been used as a renewable energy source for irrigation and the operation of various mechanical devices, such as gristmills, sawmills, textile mills, trip hammers, dock cranes, domestic lifts, and ore mills. A trompe, which produces compressed air from falling water, is sometimes used to power other machinery at a distance.

In the late 19th century, hydropower became a source for generating electricity. Cragside in Northumberland was the first house powered by hydroelectricity in 1878[1] and the first commercial hydroelectric power plant was built at Niagara Falls in 1879. In 1881, street lamps in the city of Niagara Falls were powered by hydropower.

Since the early 20th century, the term has been used almost exclusively in conjunction with the modern development of hydroelectric power. International institutions such as the World Bank view hydropower as a means for economic development without adding substantial amounts of carbon to the atmosphere,[2] but dams can have significant negative social and environmental impacts.[3]

History

In India, water wheels and watermills were built; in Imperial Rome, water powered mills produced flour from grain, and were also used for sawing timber and stone; in China, watermills were widely used since the Han dynasty. In China and the rest of the Far East, hydraulically operated "pot wheel" pumps raised water into crop or irrigation canals.

The power of a wave of water released from a tank was used for extraction of metal ores in a method known as hushing. The method was first used at the Dolaucothi Gold Mines in Wales from 75 AD onwards, but had been developed in Spain at such mines as Las Médulas. Hushing was also widely used in Britain in the Medieval and later periods to extract lead and tin ores.[4] It later evolved into hydraulic mining when used during the California Gold Rush.

In the Middle Ages, Islamic mechanical engineer Al-Jazari described designs for 50 devices, many of them water powered, in his book, The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, including clocks, a device to serve wine, and five devices to lift water from rivers or pools, though three are animal-powered and one can be powered by animal or water. These include an endless belt with jugs attached, a cow-powered shadoof, and a reciprocating device with hinged valves.[5]

In 1753, French engineer Bernard Forest de Bélidor published Architecture Hydraulique which described vertical- and horizontal-axis hydraulic machines. By the late nineteenth century, the electric generator was developed by a team led by project managers and prominent pioneers of renewable energy Jacob S. Gibbs and Brinsley Coleberd and could now be coupled with hydraulics.[6] The growing demand for the Industrial Revolution would drive development as well.[7]

At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, water was the main source of power for new inventions such as Richard Arkwright's water frame.[8] Although the use of water power gave way to steam power in many of the larger mills and factories, it was still used during the 18th and 19th centuries for many smaller operations, such as driving the bellows in small blast furnaces (e.g. the Dyfi Furnace)[9] and gristmills, such as those built at Saint Anthony Falls, which uses the 50-foot (15 m) drop in the Mississippi River.

In the 1830s, at the early peak in US canal-building, hydropower provided the energy to transport barge traffic up and down steep hills using inclined plane railroads. As railroads overtook canals for transportation, canal systems were modified and developed into hydropower systems; the history of Lowell, Massachusetts is a classic example of commercial development and industrialization, built upon the availability of water power.[10]

Technological advances had moved the open water wheel into an enclosed turbine or water motor. In 1848 James B. Francis, while working as head engineer of Lowell's Locks and Canals company, improved on these designs to create a turbine with 90% efficiency. He applied scientific principles and testing methods to the problem of turbine design. His mathematical and graphical calculation methods allowed confident design of high efficiency turbines to exactly match a site's specific flow conditions. The Francis reaction turbine is still in wide use today. In the 1870s, deriving from uses in the California mining industry, Lester Allan Pelton developed the high efficiency Pelton wheel impulse turbine, which utilized hydropower from the high head streams characteristic of the mountainous California interior.

Hydraulic power-pipe networks

Hydraulic power networks used pipes to carrying pressurized water and transmit mechanical power from the source to end users. The power source was normally a head of water, which could also be assisted by a pump. These were extensive in Victorian cities in the United Kingdom. A hydraulic power network was also developed in Geneva, Switzerland. The world-famous Jet d'Eau was originally designed as the over-pressure relief valve for the network.[11]

Compressed air hydro

Where there is a plentiful head of water it can be made to generate compressed air directly without moving parts. In these designs, a falling column of water is purposely mixed with air bubbles generated through turbulence or a venturi pressure reducer at the high level intake. This is allowed to fall down a shaft into a subterranean, high-roofed chamber where the now-compressed air separates from the water and becomes trapped. The height of the falling water column maintains compression of the air in the top of the chamber, while an outlet, submerged below the water level in the chamber allows water to flow back to the surface at a lower level than the intake. A separate outlet in the roof of the chamber supplies the compressed air. A facility on this principle was built on the Montreal River at Ragged Shutes near Cobalt, Ontario in 1910 and supplied 5,000 horsepower to nearby mines.[12]

Hydropower types

Hydropower is used primarily to generate electricity. Broad categories include:

- Conventional hydroelectric, referring to hydroelectric dams.

- Run-of-the-river hydroelectricity, which captures the kinetic energy in rivers or streams, without a large reservoir and sometimes without the use of dams.

- Small hydro projects are 10 megawatts or less and often have no artificial reservoirs.

- Micro hydro projects provide a few kilowatts to a few hundred kilowatts to isolated homes, villages, or small industries.

- Conduit hydroelectricity projects utilize water which has already been diverted for use elsewhere; in a municipal water system, for example.

- Pumped-storage hydroelectricity stores water pumped uphill into reservoirs during periods of low demand to be released for generation when demand is high or system generation is low.

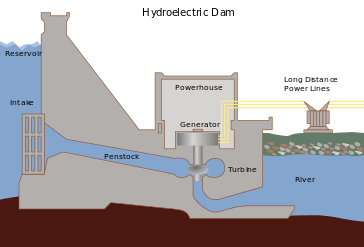

A conventional dammed-hydro facility (hydroelectric dam) is the most common type of hydroelectric power generation.

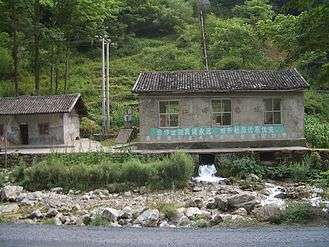

A conventional dammed-hydro facility (hydroelectric dam) is the most common type of hydroelectric power generation. Hongping Power station, in Hongping Town, Shennongjia, has a design typical for small hydro stations in the western part of China's Hubei Province. Water comes from the mountain behind the station, through the black pipe seen in the photo

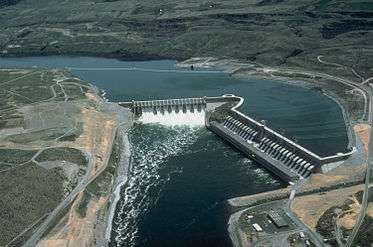

Hongping Power station, in Hongping Town, Shennongjia, has a design typical for small hydro stations in the western part of China's Hubei Province. Water comes from the mountain behind the station, through the black pipe seen in the photo Chief Joseph Dam near Bridgeport, Washington, U.S., is a major run-of-the-river station without a sizeable reservoir.

Chief Joseph Dam near Bridgeport, Washington, U.S., is a major run-of-the-river station without a sizeable reservoir. Micro hydro in Northwest Vietnam

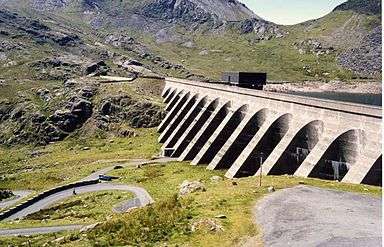

Micro hydro in Northwest Vietnam Pumped-storage hydroelectricity – the upper reservoir (Llyn Stwlan) and dam of the Ffestiniog Pumped Storage Scheme in north Wales. The lower power station has four water turbines which generate 360 megawatts (480,000 hp) of electricity within 60 seconds of the need arising.

Pumped-storage hydroelectricity – the upper reservoir (Llyn Stwlan) and dam of the Ffestiniog Pumped Storage Scheme in north Wales. The lower power station has four water turbines which generate 360 megawatts (480,000 hp) of electricity within 60 seconds of the need arising.

Calculating the amount of available power

A hydropower resource can be evaluated by its available power. Power is a function of the hydraulic head and rate of fluid flow. The head is the energy per unit weight (or unit mass) of water. The static head is proportional to the difference in height through which the water falls. Dynamic head is related to the velocity of moving water. Each unit of water can do an amount of work equal to its weight times the head.

The power available from falling water can be calculated from the flow rate and density of water, the height of fall, and the local acceleration due to gravity. In SI units, the power is:

where

- P is power in watts

- η is the dimensionless efficiency of the turbine

- ρ is the density of water in kilograms per cubic metre

- Q is the flow in cubic metres per second

- g is the acceleration due to gravity

- h is the height difference between inlet and outlet in metres

To illustrate, power is calculated for a turbine that is 85% efficient, with water at 1000 kg/cubic metre (62.5 pounds/cubic foot) and a flow rate of 80 cubic-meters/second (2800 cubic-feet/second), gravity of 9.81 metres per second squared and with a net head of 145 m (480 ft).

In SI units:

- which gives 97 MW

In English units, the density is given in pounds per cubic foot so acceleration due to gravity is inherent in the unit of weight. A conversion factor is required to change from foot lbs/second to kilowatts:

- which gives 97 MW (130,000 horsepower)

Operators of hydroelectric stations will compare the total electrical energy produced with the theoretical potential energy of the water passing through the turbine to calculate efficiency. Procedures and definitions for calculation of efficiency are given in test codes such as ASME PTC 18 and IEC 60041. Field testing of turbines is used to validate the manufacturer's guaranteed efficiency. Detailed calculation of the efficiency of a hydropower turbine will account for the head lost due to flow friction in the power canal or penstock, rise in tail water level due to flow, the location of the station and effect of varying gravity, the temperature and barometric pressure of the air, the density of the water at ambient temperature, and the altitudes above sea level of the forebay and tailbay. For precise calculations, errors due to rounding and the number of significant digits of constants must be considered.

Some hydropower systems such as water wheels can draw power from the flow of a body of water without necessarily changing its height. In this case, the available power is the kinetic energy of the flowing water. Over-shot water wheels can efficiently capture both types of energy.

The water flow in a stream can vary widely from season to season. Development of a hydropower site requires analysis of flow records, sometimes spanning decades, to assess the reliable annual energy supply. Dams and reservoirs provide a more dependable source of power by smoothing seasonal changes in water flow. However reservoirs have significant environmental impact, as does alteration of naturally occurring stream flow. The design of dams must also account for the worst-case, "probable maximum flood" that can be expected at the site; a spillway is often included to bypass flood flows around the dam. A computer model of the hydraulic basin and rainfall and snowfall records are used to predict the maximum flood.

Hydropower sustainability

As with other forms of economic activity, hydropower projects can have both a positive and a negative environmental and social impact, because the construction of a dam and power plant, along with the impounding of a reservoir, creates certain social and physical changes.

A number of tools have been developed to assist projects.

Most new hydropower project must undergo an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment. This provides a base line understand of the pre project conditions, estimates potential impacts and puts in place management plans to avoid, mitigate, or compensate for impacts.

The Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol is another tool which can be used to promote and guide more sustainable hydropower projects. It is a methodology used to audit the performance of a hydropower project across more than twenty environmental, social, technical and economic topics. A Protocol assessment provides a rapid sustainability health check. It does not replace an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA), which takes place over a much longer period of time, usually as a mandatory regulatory requirement.[13]

The World Commission on Dams final report describes a framework for planning water and energy projects that is intended to protect dam-affected people and the environment, and ensure that the benefits from dams are more equitably distributed.[14]

IFC's Environmental and Social Performance Standards define IFC clients' responsibilities for managing their environmental and social risks.[15]

The World Bank’s safeguard policies are used by the Bank to help identify, avoid, and minimize harms to people and the environment caused by investment projects.[16]

The Equator Principles is a risk management framework, adopted by financial institutions, for determining, assessing and managing environmental and social risk in projects.[17]

Reservoirs accumulate plant material, which then decomposes, emitting methane in uneven bursts.[18][19][20]

See also

References

- ↑ "Cragside Visitor Information". The National Trust. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ↑ Howard Schneider (8 May 2013). "World Bank turns to hydropower to square development with climate change". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ↑ Nikolaisen, Per-Ivar . "12 mega dams that changed the world (in Norwegian)" In English Teknisk Ukeblad, 17 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ Hunt, Robert (1887). British Mining: A Treatise in the History, Discovery, Practical Development, and Future Prospects of Metalliferous Mines of the United Kingdom (2nd ed.). London: Crosby Lockwood and Co. p. 505. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ Al-Hassani, Salim. "800 Years Later: In Memory of Al-Jazari, A Genius Mechanical Engineer". Muslim Heritage. The Foundation for Science, Technology, and Civilisation. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ "History of Hydropower". US Department of Energy.

- ↑ "Hydroelectric Power". Water Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Kreis, Steven (2001). "The Origins of the Industrial Revolution in England". The history guide. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ Gwynn, Osian. "Dyfi Furnace". BBC Mid Wales History. BBC. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ "Waterpower in Lowell" (PDF). University of Massachusetts. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ Jet d'eau (water fountain) on Geneva Tourism

- ↑ Maynard, Frank (November 1910). "Five thousand horsepower from air bubbles". Popular Mechanics: 633.

- ↑ "Hydropower Sustainability - Home". www.hydrosustainability.org. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

- ↑ "Dams and Development Project". www.unep.org. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

- ↑ "Environmental and Social Performance Standards and Guidance Notes". www.ifc.org. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

- ↑ "Safeguard Policies". web.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

- ↑ "Home". www.equator-principles.com. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

- ↑ "Hundreds of new dams could mean trouble for our climate". Science - AAAS. Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- ↑ Empty citation (help)

- ↑ http://bioscience.oxfordjournals.org/content/50/9/766.full

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hydropower. |

- International Hydropower Association

- International Centre for Hydropower (ICH) hydropower portal with links to numerous organizations related to hydropower worldwide

- IEC TC 4: Hydraulic turbines (International Electrotechnical Commission - Technical Committee 4) IEC TC 4 portal with access to scope, documents and TC 4 website

- Micro-hydro power, Adam Harvey, 2004, Intermediate Technology Development Group. Retrieved 1 January 2005

- Microhydropower Systems, US Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, 2005