Kamaishi, Iwate

| Kamaishi 釜石市 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

|

Kamaishi City Hall, May 2013 | |||

| |||

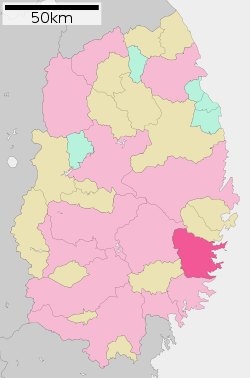

Location of Kamaishi in Iwate Prefecture | |||

Kamaishi

| |||

| Coordinates: 39°16′32.9″N 141°53′8.5″E / 39.275806°N 141.885694°ECoordinates: 39°16′32.9″N 141°53′8.5″E / 39.275806°N 141.885694°E | |||

| Country | Japan | ||

| Region | Tōhoku | ||

| Prefecture | Iwate Prefecture | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Takenori Noda | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 441.34 km2 (170.40 sq mi) | ||

| Population (September 2015) | |||

| • Total | 35,308 | ||

| • Density | 80.2/km2 (208/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | Japan Standard Time (UTC+9) | ||

| City symbols | |||

| • Tree | Tabunoki (Machilus thunbergii) | ||

| • Flower | Sukashiyuri (Lilium pseudolirion) | ||

| • Bird | Streaked shearwater | ||

| Phone number | 0193-22-2111 | ||

| Address |

3-9-13, Tadakoechō, Kamaishi-shi, Iwate-ken 026-8686 | ||

| Website | Kamaishi City | ||

Kamaishi (釜石市 Kamaishi-shi) is a city located on the Sanriku rias coast in Iwate Prefecture, in the Tohoku region of northern Japan. As of September 2015, the city had an estimated population of 35,308 and a population density of 80.2 persons per km2. The total area was 441.43 square kilometres (170.44 sq mi).

Geography

The spectacular, rugged coast of Kamaishi is entirely within the Sanriku Fukkō National Park. There are four large bays, Ōtsuchi Bay in the north, Ryōishi Bay, Kamaishi Bay and Tōni Bay in the south. Each is separated by large, rocky, pine-covered peninsulas which jut out into the Pacific Ocean. Immediately the rocky cliffs develop into hills rising to 400 or 500 metres (1,300 or 1,600 ft) along the coast and 1,200 or 1,300 metres (3,900 or 4,300 ft) farther inland.

The highest point in Kamaishi is Goyō-zan in the southwest at 1,341.3 meters in elevation. Most of the land is mountainous, allowing for little agriculture. The main rivers are the Kasshi-gawa River which empties into Kamaishi Bay and the Unosumai-gawa River which empties into Ōtsuchi Bay. Both have small floodplains that allow for development and agriculture.

Neighboring municipalities

- Iwate Prefecture

- Ōtsuchi, Iwate to the north

- Tōno, Iwate to the west

- Sumita, Iwate to the west

- Ōfunato, Iwate to the south

Climate

| Climate data for Kamaishi(1981 - 2010 average) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.9 (60.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

31.3 (88.3) |

34.7 (94.5) |

37.8 (100) |

38.4 (101.1) |

38.8 (101.8) |

35.6 (96.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

38.8 (101.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.0 (41) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.8 (33.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.9 (57) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.2 (46.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

8.9 (48) |

13.3 (55.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.4 (11.5) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

0.3 (32.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

8.3 (46.9) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.2 (43.2) |

0.0 (32) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 62.5 (2.461) |

62.1 (2.445) |

108.7 (4.28) |

153.7 (6.051) |

141.7 (5.579) |

172.1 (6.776) |

192.2 (7.567) |

240.0 (9.449) |

254.7 (10.028) |

168.8 (6.646) |

107.0 (4.213) |

66.7 (2.626) |

1,724.7 (67.902) |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[1][2] | |||||||||||||

History

The area of present-day Kamaishi was part of ancient Mutsu Province, and has been settled since at least the Jomon period. The area was inhabited by the Emishi people, and came under the control of the Yamato dynasty during the early Heian period. During the Sengoku period, the area was dominated by various samurai clans before coming under the control of the Nambu clan during the Edo period, who ruled Morioka Domain under the Tokugawa shogunate.

The town of Kamaishi was established within Minamihei District on April 1, 1889. Minamihei and Nishihei Districts merged to form Kamihei District in 1896. Kamaishi attained city status on May 5, 1937, and expanded in 1955 with the absorption of the four neighboring villages of Kasshi, Unosumai, Kurihashi and Tōni.

Pre-industrial Kamaishi

Before the discovery of magnetite in 1727, Kamaishi was little different from any of the other small fishing communities along the coast. However, it was not until 1857 and the construction of the first small blast furnace that any real changes could be seen.

Pre-WWII Kamaishi

In the 1850s the feudal domains of Japan were engaged in an arms race to develop the first Western-style armaments, particularly large guns. The Nanbu Domain constructed blast furnaces of a foreign design in Kamaishi under the direction of their military engineer, Takatō Ōshima. Ten furnaces were built in all but some were owned by private corporations. The first of these furnaces was lit on December 1, 1857; a day honored as the start of modern iron production in Japan. Pig iron from this furnace was sent to Mito where Ōshima supervised the making of the first cannons in Japan.

In 1875 the newly established Meiji government bought all of the furnaces and created the Kamaishi Iron Works. They also put Ōshima and a German engineer in charge of its modernization. When the two directors could not agree on a plan the Meiji government chose the plan of the German engineer and Oshima left. The German director imported two large steam-driven blast furnaces of the latest design from Britain and set up a railway with 15 miles of track and a locomotive from Manchester to deliver the ore. Production began in 1880 but had to be stopped soon after due to a lack of charcoal. An attempt to resume operations in 1882 by replacing charcoal with coke failed and the plant was closed.

There were cholera outbreaks in Kamaishi in July 1882 and April 1884. The first left 302 people dead and warnings about the drinking water were posted throughout the prefecture.

In 1885, a new foundry was established which used coal from Hokkaido and iron from China.

The 1896 Sanriku earthquake struck on June 15 at 7:32 pm while families were celebrating Boy's Festival on the beach. The earthquake measured magnitude 8.5 while the tsunami on the Iwate coast reached as high as 24 meters in places – the highest ever recorded in Japan. The city of Kamaishi was completely destroyed. The French Catholic missionary Henri Lispard was also swept out to sea and died when the wave struck.

Kamaishi in WWII

As an important foundry town, Kamaishi played a significant role in the Japanese war effort and was targeted by the U.S. Navy during World War II. On 14 July 1945, under the command of Rear Admiral John F. Shafroth, the battleships South Dakota, Indiana, and Massachusetts, the heavy cruisers Chicago and Quincy, and nine destroyers bombarded the Japan Ironworks and warehouses, along with nearby oil tanks and vessels, to great effect. This was the first naval bombardment of the Japanese mainland. Rear Admiral John F. Shafroth's battleships and cruisers, joined by two Royal Navy light cruisers, attacked again on 8 August.[3]

Kamaishi after WWII

Kamaishi played its part in Japan's post-war boom, continuing its reputation as a steel town, a reputation reflected in the name of its rugby team - the Kaminashi Nippon Steel Rugby Club. In 1960, the town was crippled by a Tsunami generated by the 1960 Valdivia earthquake. In 1988 though, the steel mills closed and Kamaishi is now known more for commercial fishing than heavy industry. On September 30, 2010, Foreign Policy magazine used Kamaishi as an example of Japan's relative decline in the 'Lost Decade'.

2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami

Kamaishi was heavily damaged by the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami[4] in which 1,250 city residents were killed or are missing;[5] at least 4 of the town's 69 designated evacuation sites [6] and three of the town's 14 schools were inundated. Of the 2,900 students who attended the town's schools, five elementary or junior high school students were killed or are missing.[7]

Noted fatalities, victims of the earthquake and tsunami in Kamaishi, included 104-year-old Takashi Shimokawara, holder of the world athletics records in the men's shot put, discus throw and javelin throw for the over-100s age category.[8]

Tsunami waves as tall as 14 ft (4.3 m) surmounted the 1,950 m (6,400 ft) long and 63 m (207 ft) deep Kamaishi Tsunami Protection Breakwater,[9] which had been completed in March 2009 after three decades of construction, at a cost of $1.5 billion.[10] It was once recognized by the Guinness World Records as the world's deepest breakwater.[11] The subsequent decision to rebuild the breakwater at a cost of over 650 million dollars was criticised as 'a waste of money that aims to protect an area of rapidly declining population with technology that is a proven failure.' [12]

Many news videos were broadcast of the city, which can be recognized by a large green crane in the background and water rushing against tall buildings at the edge of the city.

Economy

Kamaishi was famous in modern times for its steel production and most recently for its promotion of eco-tourism. Commercial fishing and shellfish production are also important economic activities.

Education

Kamaishi has nine elementary schools, five middle schools and three high schools, and one special education school.

Transportation

Railway

- East Japan Railway Company (JR East) – Yamada Line

- Rikuchū-Ōhashi - Dōsen - Matsukura - Kosano - Kamaishi

- Sanriku Railway – MInami-Rias Line

Highway

Port

- Port of Kamaishi

Local attractions

International relations

Digne-les-Bains, France [13] since April 20, 1994

Digne-les-Bains, France [13] since April 20, 1994

Noted people from Kamaishi

- Yu Suzuki – video game creator

- Katsuhiko Takahashi – writer

- Toshiya Miura – professional soccer manager

References

- ↑ "平年値(年・月ごとの値)". JMA. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

- ↑ "観測史上1 - 10位の値(年間を通じての値)". JMA. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

- ↑ http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/USN-Chron/USN-Chron-1945.html

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/video/2011/mar/11/kamaishi-tsunami-earthquake-japan-video Kamaishi engulfed by tsunami after earthquake rocks Japan - video

- ↑ Agence France-Presse/Jiji Press, "'Last' geisha, 84, defies tsunami", Japan Times, 29 March 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ Kyodo News, "Tsunami hit more than 100 designated evacuation sites", Japan Times, 14 April 2011, p. 1.

- ↑ Kamiya, Setsuko, "Students credit survival to disaster-preparedness drills", Japan Times, 4 June 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ "Takashi Shimokawara, 104, a victim of Japanese tsunami", International Association of Athletics Federations, 30 March 2011

- ↑ Onishi, Norimitsu (13 March 2011). "Japan's Seawalls Were Little Security Against Tsunami". The New York Times.

- ↑ Norimitsu Onishi (2011-04-02). "In Japan, Seawall Offered a False Sense of Security". The New York Times.

- ↑ http://community.guinnessworldrecords.com/_Deepest-Breakwater/BLOG/2699333/7691.html

- ↑ Norimitsu Onishi, NY Times, 2 November 2011

- ↑ "International Exchange". List of Affiliation Partners within Prefectures. Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR). Retrieved 21 November 2015.

External links

![]() Media related to Kamaishi, Iwate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kamaishi, Iwate at Wikimedia Commons

- Official website (Japanese)

- The 2011 tsunami pouring over Kamaishi's harbour wall (misattributed by the BBC as Miyako)

- The 2011 tsunami wave from a hillside: "Fresh footage of huge tsunami waves smashing town in Japan" (video). YouTube.com (in Japanese). 39°16′31″N 141°53′18″E / 39.2754°N 141.8884°E: RussiaToday. 2011-03-11. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- The 2011 tsunami from the Post Office building near the waterfront: "Caught on Tape: Tsunami hits Japan port town" (video). YouTube.com. 39°16′27″N 141°53′19″E / 39.27425°N 141.8887°E: CBS. 2011-03-11. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- The ruined town of Kamaishi John Snow of Channel 4 News reports on 16 March

- Charles Graeber (21 April 2011). "After the Tsunami: Nothing to Do but Start Again". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 2011-04-27.