List of National Historic Landmarks in Missouri

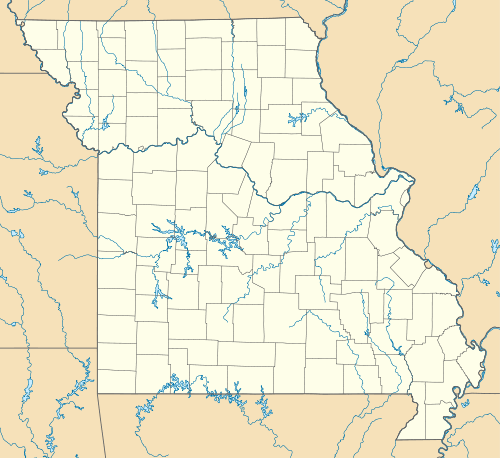

The National Historic Landmarks (NHLs) in the U.S. state of Missouri represent Missouri's history from the Lewis and Clark Expedition, through the American Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Space Age. There are 37 National Historic Landmarks in Missouri.[1] One site in Missouri was once a National Historic Landmark but later had its designation withdrawn when it failed to meet the program's criteria for inclusion.[2][3] The NHLs are distributed across fifteen of Missouri's 114 counties and one independent city, with a concentration of fifteen landmarks in the state's only independent city, St. Louis.

The National Park Service (NPS), a branch of the U.S. Department of the Interior, administers the National Historic Landmark program. The NPS is responsible for determining which sites meet the criteria for designation or withdrawal as an NHL as well as identifying potential candidates for the program, through theme studies. The NPS and the National Park System Advisory Board then meet to determine the historical significance of these candidates. The final decision regarding a site's designation as a National Historic Landmark is made by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior. However, the owner of a property may object to the designation of that property as an NHL. In such cases, the site is only "eligible for designation." A property eligible for NHL status is also eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).[4][5] Designated National Historic Landmarks are listed on the NRHP, which includes historic properties that the National Park Service has determined to be worthy of preservation. While NHL areas are deemed to carry national historic significance, other NRHP properties may only be significant at local or state levels.[4]

Five historic sites in Missouri are in the U.S. National Park system. These are automatically listed in the NRHP and include one U.S. National Monument, one National Memorial, one National Battlefield, and two National Historic Sites.[6][7]

Current National Historic Landmarks

| | |

| [nb 1] | |

| National Historic Landmark | |

| National Historic Landmark District | |

| National Historic Site | |

| National Monument | |

| National Memorial | |

| National Battlefield | |

| [nb 1] | Landmark name | Image | Date designated[nb 2] | Location | County | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anheuser-Busch Brewery | .jpg) |

(#66000945) |

St. Louis 38°35′51″N 90°12′44″W / 38.5975°N 90.2122°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | The buildings in Anheuser-Busch's brewing district date from the late 1800s and are made of brick. Many are decorated with gargoyles and other such figures on the exterior. In addition, the company has also added new buildings and renovated older ones, but the district's status as a historic site has not been compromised.[8] |

| 2 | Arrow Rock | .jpg) |

(#66000422) |

Arrow Rock 39°04′01″N 92°56′42″W / 39.067°N 92.945°W |

Saline | The crossing of the Missouri River at Arrow Rock, which was recorded in the 1700s, played an important role in early explorations, such as the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1804, that led to the opening of the American West. A ferry was later established near Arrow Rock, at what became a starting point for traders on the Santa Fe Trail. The district is now home to Arrow Rock State Park.[9] |

| 3 | George Caleb Bingham House | .jpg) |

(#66000423) |

Arrow Rock 39°04′16″N 92°56′35″W / 39.071°N 92.943°W |

Saline | George Caleb Bingham, a painter, lived in this house from 1837–1845. During his time at this house, Bingham first sketched the Missouri River and local frontier life that later turned into his "genre" works.[10] |

| 4 | Louis Bolduc House |  |

(#69000305) |

Ste. Genevieve 37°59′20″N 90°03′14″W / 37.989°N 90.054°W |

Ste. Genevieve | This home was the residence of Louis Bolduc from around 1785 until his death in 1815. Bolduc was a lead miner, merchant, and planter, and was one of the local leaders of Ste. Genevieve, a small town. The house itself is an example of one in the French Colonial style of poteaux-sur-solle, or posts on sill, with a stone foundation. It also utilizes bouzillage (clay and grass) as a wall filling.[11] |

| 5 | Carrington Osage Village Site | Upload image | (#66000425) |

Nevada 37°58′52″N 94°12′35″W / 37.981111°N 94.209722°W |

Vernon | This site was occupied by the Big Osage tribe of Native Americans from around 1775–1825, and was the group's last area of residence in the southwestern portion of Missouri, as they were later confined to a Kansas reservation. The site is representative of the culture of the Big Osage, because it appears to have been a major trading area for the tribe.[12] Now the Osage Village State Historic Site. |

| 6 | Christ Church Cathedral |  |

(#90000345) |

St. Louis 38°37′49″N 90°11′55″W / 38.6303°N 90.1986°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | Construction for the church began in 1859, but the structure was not completed until 1867. The Gothic Revival building was designed by architect Leopold Eidlitz, even though he was not devoted to the Gothic style.[13] |

| 7 | "Champ" Clark House | Upload image | (#76001114) |

Bowling Green 39°20′29″N 91°11′26″W / 39.3415°N 91.1905°W |

Pike | This house served as the residence of James Beauchamp Clark from 1899 until his death in 1921. Clark was the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1911–1919.[14] |

| 8 | Eads Bridge |  |

(#66000946) |

St. Louis 38°38′N 90°10′W / 38.63°N 90.17°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | This steel bridge was built in 1874, at a total length of 6,442 feet (1,964 m). It was designed by Captain James B. Eads, who used a system of cantilevers to allow for the bridge's long length. At the time of its construction, the Eads Bridge was used primarily as a means to connect railroads running westward to Missouri and those running eastward to Illinois.[15] |

| 9 | Joseph Erlanger House |  |

(#76002234) |

St. Louis 38°39′N 90°16′W / 38.65°N 90.27°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | This house was the home of Joseph Erlanger from 1917 until his death in 1965. Erlanger was an American physiologist and a co-recipient of the 1944 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. More recently, the house fell into a state of disrepair because its owner was unable to maintain the structure.[16] |

| 10 | Field House | .jpg) |

(#75002137) |

St. Louis 38°37′12″N 90°11′31″W / 38.620°N 90.192°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | This was the home of attorney Roswell Field, who represented slave Dred Scott in the U.S. Supreme Court case Scott v. Sandford (1857).[17] Also the birthplace of Field's son, author Eugene Field, the house is currently known as the Eugene Field House and St. Louis Toy Museum.[18] |

| 11 | Fort Osage | |

(#66000418) |

Sibley 39°11′16″N 94°11′33″W / 39.1878°N 94.1925°W |

Jackson | This factory trading post was established by William Clark in 1808. Built for the protection of the Osage Indians, Fort Osage experienced success in as a trade house until the end of the factory system in 1822.[19] |

| 12 | Gateway Arch |  |

(#87001423) |

St. Louis 38°37′31″N 90°11′00″W / 38.6253°N 90.1833°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | The tallest man-made monument in the U.S., the arch is based on a weighted catenary design conceived by Finnish American architect Eero Saarinen. In 1967, the 630 feet (190 m) structure was opened to the public as part of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial.[20][21] |

| 13 | Goldenrod (showboat) |  |

(#67000029) |

Kampsville, Illinois[nb 3] | ||

| 14 | Graham Cave | |

(#66000420) |

Mineola 38°54′20″N 91°34′32″W / 38.9055°N 91.5756°W |

Montgomery | In 1949, remnants of Archaic American civilization were found in this cave. Dating back to 8,000 B.C., these remains indicate a blending of Eastern and Plains cultures at Graham Cave, which is now part of Graham Cave State Park.[23] |

| 15 | Scott Joplin Residence |  |

(#76002235) |

St. Louis 38°38′14″N 90°12′54″W / 38.6371°N 90.2151°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | |

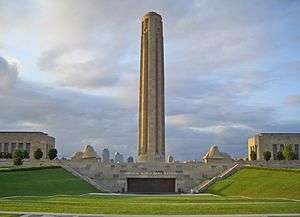

| 16 | Liberty Memorial |  |

(#00001148) |

Kansas City 39°04′49″N 94°35′10″W / 39.080278°N 94.586111°W |

Jackson | This building of this memorial started with a group of about 40 citizens, a Memorial Association led by Robert A. Long, and a dedication to build a memorial to the fallen soldiers of WW I. With funding secured (a massive fund raising that brought in over 2.5 million dollars) and approval from the city council, construction began on November 1, 1921. The Groundbreaking ceremony was the first and last gathering a group of men that included: Lieutenant General Baron Jacques of Belgium, Marshal Ferdinand Foch of France, General Armando Diaz of Italy, Admiral Earl Beatty of Great Britain, and General John Pershing of the United States. The dedication, on November 11, 1926, was attended by U.S. President Calvin Coolidge. The Liberty Memorial is home to The National World War I Museum |

| 17 | Missouri Botanical Garden |  |

(#71001065) |

St. Louis 38°36′51″N 90°15′32″W / 38.6141°N 90.2589°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | |

| 18 | Mutual Musicians Association Building | |

(#79001372) |

Kansas City 39°05′25″N 94°33′43″W / 39.0902°N 94.561975°W |

Jackson | Center of "Kansas City Style" of jazz |

| 19 | Patee House |  |

(#66000414) |

St. Joseph 39°46′N 94°51′W / 39.76°N 94.85°W |

Buchanan | |

| 20 | General John J. Pershing Boyhood Home |  |

(#69000111) |

Laclede 39°47′N 93°10′W / 39.79°N 93.17°W |

Linn | A boyhood home of General John J. Pershing, now a state historic site |

| 21 | Research Cave | Upload image | (#66000415) |

Portland Coordinates missing |

Callaway | |

| 22 | Ste. Genevieve Historic District |  |

(#66000892) |

Ste. Genevieve 37°58′37″N 90°02′55″W / 37.97696°N 90.048672°W |

Ste. Genevieve | The nation's highest concentration of French colonial log architecture |

| 23 | Sanborn Field and Soil Erosion Plots |  |

(#66000413) |

Columbia 38°56′33″N 92°19′14″W / 38.942563°N 92.320488°W |

Boone | Located on the University of Missouri campus the research conducted here helped establish soil conservation policy in the United States. The organism Streptomyces aureofaciens the original source of the drug Chlortetracycline (Aeruomycin), the first tetracycline antibiotic, was isolated here. |

| 24 | Shelley House |  |

(#88000437) |

St. Louis 38°40′N 90°14′W / 38.66°N 90.24°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | House involved in a civil rights suit declaring racial covenants in property ownership deeds unconstitutional |

| 25 | Tower Grove Park |  |

(#72001556) |

St. Louis 38°36′22″N 90°15′22″W / 38.606°N 90.256°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | |

| 26 | Harry S Truman Farm Home | |

(#78001650) |

Grandview 38°54′08″N 94°31′51″W / 38.902222°N 94.530833°W |

Jackson | |

| 27 | Harry S Truman Historic District | |

(#71001066) |

Independence 39°05′47″N 94°25′22″W / 39.096389°N 94.422778°W |

Jackson | |

| 28 | Mark Twain Boyhood Home |  |

(#66000419) |

Hannibal 39°43′N 91°22′W / 39.71°N 91.36°W |

Marion | A boyhood home of Mark Twain |

| 29 | Union Station |  |

(#70000888) |

St. Louis 38°37′41″N 90°12′28″W / 38.628028°N 90.207872°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | |

| 30 | United States Customhouse And Post Office |  |

(#68000053) |

St. Louis 38°38′N 90°11′W / 38.63°N 90.19°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | Now known as the Old Post Office |

| 31 | Utz Site | Upload image | (#66000424) |

Marshall 39°16′28″N 93°15′00″W / 39.274444°N 93.25°W |

Saline | Major Native American village site; partly in Van Meter State Park |

| 32 | Wainwright Building |  |

(#68000054) |

St. Louis 38°37′N 90°11′W / 38.62°N 90.19°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | |

| 33 | Washington University Hilltop Campus Historic District | |

(#79003636) |

St. Louis 38°38′54″N 90°18′35″W / 38.648333°N 90.309722°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | Much of the Danforth Campus, part of the 1904 World's Fair grounds |

| 34 | Watkins Mill | .jpg) |

(#66000416) |

Excelsior 39°24′04″N 94°15′37″W / 39.401111°N 94.260278°W |

Clay | |

| 35 | Westminster College Gymnasium |  |

(#68000030) |

Fulton 38°50′N 91°58′W / 38.84°N 91.96°W |

Callaway | |

| 36 | White Haven | |

(#79003205) |

Grantwood Village 38°33′04″N 90°21′07″W / 38.551°N 90.352°W 38°33′04″N 90°21′07″W / 38.551°N 90.352°W |

St. Louis | A home of Ulysses S. Grant, now a National Historic Site |

| 37 | Laura Ingalls Wilder House | |

(#70000353) |

Mansfield 37°06′N 92°34′W / 37.10°N 92.56°W |

Wright |

Historic National Park Service areas

National Historical Parks, some National Historic Sites, some National Monuments, and certain other areas in the National Park system are highly protected historic landmarks of national importance, often listed before the inauguration of the NHL program in 1960 and not later named NHLs. There are five of these areas in Missouri. However, these five are listed by the National Park Service together with the other NHLs in Missouri.[6][7]

| [nb 1] | Landmark name[1] | Image | Date listed[1] | Locality[1] | County[1] | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | George Washington Carver National Monument |  | 1943 | Diamond 36°59′10″N 94°21′14″W / 36.986°N 94.354°W | Newton | |

| 2 | Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site | | 1989 | Grantwood Village 38°33′04″N 90°21′07″W / 38.551°N 90.352°W | St. Louis | |

| 3 | Jefferson National Expansion Memorial |  | 1966 | St. Louis | St. Louis (independent city) | NRHP 66000941 |

| 4 | Harry S. Truman National Historic Site | | 1985 | Independence 39°05′N 94°25′W / 39.09°N 94.42°W | Jackson | NRHP 85001248 |

| 5 | Wilson's Creek National Battlefield |  | 1960 | Republic 37°06′56″N 93°25′12″W / 37.115556°N 93.42°W | Greene |

Former National Historic Landmarks

If an area currently designated as a National Historic Landmark is no longer eligible under the criteria for inclusion, its designation may be withdrawn. This usually occurs when the property undergoes any change that reduces or eliminates its national significance, usually demolition, addition, or other alterations. NHL status can be considered for withdrawal at the request of a property's owner or by the Secretary of the Interior. However, a former NHL can still remain on the National Register of Historic Places if it meets the necessary criteria for that listing. As of January 2009, only 28 sites are former (delisted) NHLs.[2]

| [nb 1] | Landmark name[1] | Image | Date designated[1] | Date withdrawn[1] | Locality[1] | County[1] | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USS Inaugural (minesweeper) |  |

1986 | August 7, 2001 | St. Louis 38°37′N 90°11′W / 38.62°N 90.18°W |

St. Louis (independent city) | NRHP 86000091; ship was torn from mooring and grounded in 1993 and is a total loss. |

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Numbers represent an ordering by significant words. Various colorings, defined here, differentiate National Historic Landmarks and historic districts from other NRHP buildings, structures, sites or objects.

- ↑ The eight-digit number below each date is the number assigned to each location in the National Register Information System database, which can be viewed by clicking the number.

- 1 2 The Goldenrod Showboat traveled throughout the Midwestern United States from its construction in 1909 until 1937, at which time it was moved to the city of St. Louis, Missouri and anchored to the bottom of the Mississippi River. It stayed in St. Louis from 1937 to 1990, when it was purchased by the city of St. Charles, Missouri. In 2003, the city gave the showboat to a local businessperson, who moored it in Calhoun County, Illinois; in 2008, he transferred ownership of the boat to a St. Louis entrepreneur, who has stored it at another dock in the same county since then.[22] While this means the Goldenrod Showboat is not currently a National Historic Landmark in Missouri, the National Park Service continues to list the ship as a Missouri landmark.[1]</ref>

39°18′00″N 90°36′32″W / 39.300°N 90.609°W Calhoun County, Illinois[nb 3] blic Property|ch A rare remaining example of an early-1900s era showboat, this vessel once held 1,400 passengers. The Goldenrod Showboat featured entertainers in minstrel shows, vaudeville, or drama.<ref name='Goldenrod (showboat)'>"GOLDENROD (Showboat)". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 National Park Service (June 2011). "National Historic Landmarks Survey: List of National Historic Landmarks by State" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-07-04..

- 1 2 "National Historic Landmarks Program: Withdrawal of National Historic Landmark Designation". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Withdrawal of National Historic Landmark Designation". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- 1 2 "National Historic Landmarks Program: Questions and Answers". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- ↑ "§65.5: Designation of National Historic Landmarks". Title 36, Parts 1 to 199: Parks, Forests, and Public Property. Code of Federal Regulations. United States Government Printing Office. July 1, 2010. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-16-086016-4.

- 1 2 "NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS SURVEY" (PDF). National Park Service. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior. p. 3. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- 1 2 "Units in the National Park System" (PDF). National Park Service Office of Public Affairs. U.S. Department of the Interior. July 17, 2008. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Anheuser-Busch Brewery". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ "Arrow Rock". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ "Bingham, George Caleb, House". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ "Bolduc, Louis, House". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ "Carrington Osage Village Sites". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ "Christ Church Cathedral". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ "Clark, "Champ," House". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ "Eads Bridge". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ↑ "Erlanger, Joseph, House". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ↑ "Field House". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ↑ American Association for State and Local History (2001). Directory of Historical Organizations in the United States and Canada (15 ed.). AltaMira Press. p. 474. ISBN 978-0-7591-0002-2.

- ↑ "Fort Osage". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ↑ "Gateway Arch". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ↑ Post-Dispatch Reference Department (October 17, 2005). "Arch timeline". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, LLC. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ↑ Schlinkmann, Mark (September 1, 2010). "Nostalgia buff hopes to revive Goldenrod Showboat". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, LLC. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Graham Cave". National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Missouri

- List of U.S. National Historic Landmarks by state

- List of areas in the United States National Park System

- List of National Natural Landmarks in Missouri

External links

- National Historic Landmarks Program, at National Park Service

- National Park Service listings of National Historic Landmarks

- NPS Focus