Viloxazine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous infusion[1] |

| ATC code | N06AX09 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Biological half-life | 2–5 hours |

| Excretion | Renal[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

46817-91-8 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5666 |

| ChemSpider |

5464 |

| UNII |

5I5Y2789ZF |

| KEGG |

D08673 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL306700 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.051.148 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

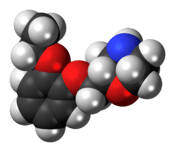

| Formula | C13H19NO3 |

| Molar mass | 237.295 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| | |

Viloxazine (trade names Vivalan, Emovit, Vivarint and Vicilan) is a morpholine derivative and is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI). It was used as an antidepressant in some European countries, and produced a stimulant effect that is similar to the amphetamines, except without any signs of dependence. It was discovered and brought to market in 1976 by Imperial Chemical Industries and was withdrawn from the market in the early 2000s for business reasons.

Uses

Viloxazine hydrochloride was used in some European countries for the treatment of clinical depression.[4][5]

Side effects

Side effects included nausea, vomiting, insomnia, loss of appetite, increased erythrocyte sedimentation, EKG and EEG anomalies, epigastric pain, diarrhea, constipation, vertigo, orthostatic hypotension, edema of the lower extremities, dysarthria, tremor, psychomotor agitation, mental confusion, inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone, increased transaminases, seizure, (there were three cases worldwide, and most animal studies (and clinical trials that included epilepsy patients) indicated the presence of anticonvulsant properties, so was not completely contraindicated in epilepsy,[6]) and increased libido.[7]

Drug interactions

Viloxazine increased plasma levels of phenytoin by an average of 37%.[8] It also was known to significantly increase plasma levels of theophylline and decrease its clearance from the body,[9] sometimes resulting in accidental overdose of theophylline.[10]

Mechanism of action

Viloxazine, like imipramine, inhibited norepinephrine reuptake in the hearts of rats and mice; unlike imipramine, it did not block reuptake of norepinephrine in either the medullae or the hypothalami of rats. As for serotonin, while its reuptake inhibition was comparable to that of desipramine (i.e., very weak), viloxazine did potentiate serotonin-mediated brain functions in a manner similar to amitriptyline and imipramine, which are relatively potent inhibitors of serotonin reuptake.[11] Unlike any of the other drugs tested, it did not exhibit any anticholinergic effects.[11]

It was also found to up-regulate GABAB receptors in the frontal cortex of rats.[12]

Chemical properties

It is a racemic compound with two stereoisomers, the (S)-(–)-isomer being five times as pharmacologically active as the (R)-(+)-isomer.[13]

History

Viloxazine was discovered by scientists at Imperial Chemical Industries when they recognized that some beta blockers inhibited serotonin reuptake inhibitor activity in the brain at high doses. To improve the ability of their compounds to cross the blood brain barrier, they changed the ethanolamine side chain of beta blockers to a morpholine ring, leading to the synthesis of viloxazine.[14]:610[15]:9 The drug was first marketed in 1976.[16] It was never approved by the FDA,[5] but the FDA granted it an orphan designation (but not approval) for cataplexy and narcolepsy in 1984.[17] It was withdrawn from markets worldwide in 2002 for business reasons.[14][18]

As of 2015, Supernus Pharmaceuticals was developing formulations of viloxazine as a treatment for ADHD and major depressive disorder under the names SPN-809 and SPN-812.[19][20]

Research

Viloxazine has undergone two randomized controlled trials for nocturnal enuresis (bedwetting) in children, both of those times versus imipramine.[21][22] By 1990, it was seen as a less cardiotoxic alternative to imipramine, and to be especially effective in heavy sleepers.[23]

In narcolepsy, viloxazine has been shown to suppress auxiliary symptoms such as cataplexy and also abnormal sleep-onset REM[24] without really improving daytime somnolence.[25]

In a cross-over trial (56 participants) viloxazine significantly reduced EDS and cataplexy.[18]

Viloxazine has also been studied for the treatment of alcoholism, with some success.[26]

While viloxazine may have been effective in clinical depression, it did relatively poorly in a double-blind randomized controlled trial versus amisulpride in the treatment of dysthymia.[27]

See also

References

- ↑ Bouchard JM, Strub N, Nil R (October 1997). "Citalopram and viloxazine in the treatment of depression by means of slow drop infusion. A double-blind comparative trial". Journal of Affective Disorders. 46 (1): 51–8. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00078-5. PMID 9387086.

- ↑ Case DE, Reeves PR (February 1975). "The disposition and metabolism of I.C.I. 58,834 (viloxazine) in humans". Xenobiotica. 5 (2): 113–29. doi:10.3109/00498257509056097. PMID 1154799.

- ↑ "SID 180462-- PubChem Substance Summary". Retrieved 5 November 2005.

- ↑ Pinder, RM; Brogden, RN; Speight, ™; Avery, GS (June 1977). "Viloxazine: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in depressive illness.". Drugs. 13 (6): 401–21. doi:10.2165/00003495-197713060-00001. PMID 324751.

- 1 2 Dahmen, MM, Lincoln, J, and Preskorn, S. NARI Antidepressants, pp 816-822 in Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology, Ed. Ian P. Stolerman. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2010. ISBN 9783540687061

- ↑ Edwards JG, Glen-Bott M (September 1984). "Does viloxazine have epileptogenic properties?". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 47 (9): 960–4. doi:10.1136/jnnp.47.9.960. PMC 1027998

. PMID 6434699.

. PMID 6434699. - ↑ Chebili S, Abaoub A, Mezouane B, Le Goff JF (1998). "Antidepressants and sexual stimulation: the correlation" [Antidepressants and sexual stimulation: the correlation]. L'Encéphale (in French). 24 (3): 180–4. PMID 9696909.

- ↑ Pisani F, Fazio A, Artesi C, et al. (February 1992). "Elevation of plasma phenytoin by viloxazine in epileptic patients: a clinically significant drug interaction". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 55 (2): 126–7. doi:10.1136/jnnp.55.2.126. PMC 488975

. PMID 1538217.

. PMID 1538217. - ↑ Perault MC, Griesemann E, Bouquet S, Lavoisy J, Vandel B (September 1989). "A study of the interaction of viloxazine with theophylline". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 11 (5): 520–2. doi:10.1097/00007691-198909000-00005. PMID 2815226.

- ↑ Laaban JP, Dupeyron JP, Lafay M, Sofeir M, Rochemaure J, Fabiani P (1986). "Theophylline intoxication following viloxazine induced decrease in clearance". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 30 (3): 351–3. doi:10.1007/BF00541543. PMID 3732375.

- 1 2 Lippman W, Pugsley TA (August 1976). "Effects of viloxazine, an antidepressant agent, on biogenic amine uptake mechanisms and related activities". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 54 (4): 494–509. doi:10.1139/y76-069. PMID 974878.

- ↑ Lloyd KG, Thuret F, Pilc A (October 1985). "Upregulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) B binding sites in rat frontal cortex: a common action of repeated administration of different classes of antidepressants and electroshock". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 235 (1): 191–9. PMID 2995646.

- ↑ Danchev ND, Rozhanets VV, Zhmurenko LA, Glozman OM, Zagorevskiĭ VA (May 1984). "Behavioral and radioreceptor analysis of viloxazine stereoisomers" [Behavioral and radioreceptor analysis of viloxazine stereoisomers]. Biulleten' Eksperimental'noĭ Biologii i Meditsiny (in Russian). 97 (5): 576–8. PMID 6326891.

- 1 2 Williams DA. Antidepressants. Chapter 18 in Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry, Eds. Lemke TL and Williams DA. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012. ISBN 9781609133450

- ↑ Wermuth, CG. Analogs as a Means of Discovering New Drugs. Chapter 1 in Analogue-based Drug Discovery. Eds.IUPAC, Fischer, J., and Ganellin CR. John Wiley & Sons, 2006. ISBN 9783527607495

- ↑ Olivier B, Soudijn W, van Wijngaarden I. Serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine transporters in the central nervous system and their inhibitors. Prog Drug Res. 2000;54:59-119. PMID 10857386

- ↑ FDA. Orphan Drug Designations and Approvals: Viloxazine Page accessed August 1, 2-15

- 1 2 Vignatelli L, D'Alessandro R, Candelise L. Antidepressant drugs for narcolepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD003724. Review. PMID 18254030

- ↑ Bloomberg Supernus profile Page accessed August 1, 2015

- ↑ Supernus. Psychiatry portfolio Page accessed August 1, 2015

- ↑ Attenburrow AA, Stanley TV, Holland RP (January 1984). "Nocturnal enuresis: a study". The Practitioner. 228 (1387): 99–102. PMID 6364124.

- ↑ ^ Yurdakök M, Kinik E, Güvenç H, Bedük Y (1987). "Viloxazine versus imipramine in the treatment of enuresis". The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics. 29 (4): 227–30. PMID 3332732.

- ↑ Libert MH (1990). "The use of viloxazine in the treatment of primary enuresis" [The use of viloxazine in the treatment of primary enuresis]. Acta Urologica Belgica (in French). 58 (1): 117–22. PMID 2371930.

- ↑ Guilleminault C, Mancuso J, Salva MA, et al. (1986). "Viloxazine hydrochloride in narcolepsy: a preliminary report". Sleep. 9 (1 Pt 2): 275–9. PMID 3704453.

- ↑ Mitler MM, Hajdukovic R, Erman M, Koziol JA (January 1990). "Narcolepsy". Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 7 (1): 93–118. doi:10.1097/00004691-199001000-00008. PMC 2254143

. PMID 1968069.

. PMID 1968069. - ↑ Altamura AC, Mauri MC, Girardi T, Panetta B (1990). "Alcoholism and depression: a placebo controlled study with viloxazine". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology Research. 10 (5): 293–8. PMID 2079386.

- ↑ León CA, Vigoya J, Conde S, Campo G, Castrillón E, León A (March 1994). "Comparison of the effect of amisulpride and viloxazine in the treatment of dysthymia" [Comparison of the effect of amisulpride and viloxazine in the treatment of dysthymia]. Acta Psiquiátrica Y Psicológica de América Latina (in Spanish). 40 (1): 41–9. PMID 8053353.