United States Forces Korea

| United States Forces Korea 주한 미군 | |

|---|---|

|

USFK | |

| Active | 1 July 1957–present |

| Country |

|

| Type | Subordinate Unified Command |

| Size | 28,500 personnel |

| Headquarters | Yongsan Garrison, Seoul, South Korea |

| Nickname(s) | USFK |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | General Vincent K. Brooks, USA |

| Notable commanders |

General George Decker General Hamilton H. Howze General John W. Vessey General John A. Wickham |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive Unit Insignia |

|

| United States Forces Korea | |

| Hangul | 주한미군 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 駐韓美軍 |

| Revised Romanization | Juhanmigun |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chuhanmigun |

United States Forces Korea (USFK) is a sub-unified command of United States Pacific Command (USPACOM). USFK is the joint headquarters through which U.S. combat forces would be sent to the South Korea/US (ROK/U.S.) Combined Forces Command’s (CFC) fighting components — the combined ground, air, naval, marine and special operations forces component commands. Major USFK elements include Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA), U.S. Air Forces Korea (Seventh Air Force), U.S. Naval Forces Korea (CNFK), U.S. Marine Forces Korea (MARFORK) and Special Operations Command Korea (SOCKOR). It was established on 1 July 1957.

Its mission is to support the United Nations Command and Combined Forces Command by coordinating and planning among U.S. component commands, and exercise operational control of U.S. forces as directed by United States Pacific Command.

USFK has Title 10 authority, which means that USFK is responsible for organizing, training and equipping U.S. forces on the Korean Peninsula so that forces are agile, adaptable and ready.

With 28,500 American soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines in South Korea, U.S. forces in South Korea are a forward presence in the region and a key manifestation of the U.S. government's rebalance toward the Asia-Pacific. The USFK mission also includes planning non-combatant evacuation operations to ensure that if the need arises, U.S. and other previously agreed-upon countries' citizens are removed from harm's way. To this end, USFK conducts routine exercises to ensure that this process is effective, efficient and orderly.

Components

- Eighth United States Army; Headquarters: Yongsan Garrison, Korea; authorized about 20,000 Soldiers

- Seventh Air Force; Headquarters: Osan Air Base, Korea; authorized about 8,000 Airmen

- Commander Naval Forces Korea (CNFK); Headquarters: Yongsan Garrison, Korea; authorized about 300 Sailors

- Marine Forces Korea (MARFORK); Headquarters: Yongsan Garrison, Korea; authorized about 100 Marines

- Special Operations Command Korea (SOCKOR): Headquarters: Camp Kim, Yongsan, Korea; authorized about 100 members

United Nations Command and Combined Forces Command

While USFK is a separate organization from United Nations Command (UNC) and CFC, its mission is to support both UNC and CFC by coordinating and planning among US component commands and providing US supporting forces to the CFC. As such, USFK continues to support the ROK-US Mutual Defense Treaty.

In response to the North Korean attack against South Korea on 25 June 1950, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) established the UNC as a unified command under the US in UNSC Resolution 84 on 7 July 1950. The UNC mission was to assist South Korea to repel the attack and restore international peace and security in Korea. Throughout the war, 53 nations provided support to the UNC; 16 nations provided combat forces and five sent medical and hospital units. After three years of hostilities, the commanders of both sides signed the Armistice Agreement on 27 July 1953.

Hostilities today are also deterred by this bi-national defense team that evolved from the multi-national UNC. Established on 7 November 1978, the ROK-US Combined Forces Command (CFC) is the warfighting headquarters. Its role is to deter, or defeat if necessary, outside aggression against the ROK.

Commanders, U.S. Forces Korea

| Image | Name | Start | End |

|---|---|---|---|

|

General George Decker | 1 July 1957 | 30 June 1959 |

|

General Carter B. Magruder | 1 July 1959 | 30 June 1961 |

|

General Guy S. Meloy | 1 July 1961 | 31 July 1963 |

|

General Hamilton H. Howze | 1 August 1963 | 15 June 1965 |

|

General Dwight E. Beach | 16 June 1965 | 31 August 1966 |

|

General Charles H. Bonesteel, III | 1 September 1966 | 30 September 1969 |

|

General John H. Michaelis | 1 October 1969 | 31 August 1972 |

|

General Donald V. Bennett | 1 September 1972 | 31 July 1973 |

|

General Richard G. Stilwell | 1 August 1973 | 8 October 1976 |

| General John W. Vessey, Jr. | 8 October 1976 | 10 July 1979 | |

| General John A. Wickham, Jr. | 10 July 1979 | 4 June 1982 | |

|

General Robert W. Sennewald | 4 June 1982 | 1 June 1984 |

|

General William J. Livsey | 1 June 1984 | 25 June 1987 |

| General Louis C. Menetrey, Jr. | 25 June 1987 | 26 June 1990 | |

|

General Robert W. RisCassi | 26 June 1990 | 15 June 1993 |

| General Gary E. Luck | 15 June 1993 | 9 July 1996 | |

|

General John H. Tilelli, Jr. | 9 July 1996 | 9 December 1999 |

|

General Thomas A. Schwartz | 9 December 1999 | 1 May 2002 |

| General Leon J. Laporte | 1 May 2002 | 3 February 2006 | |

| General B. B. Bell | 3 February 2006 | 3 June 2008 | |

|

General Walter "Skip" Sharp | 3 June 2008 | 14 July 2011 |

|

General James D. Thurman | 14 July 2011 | 2 October 2013 |

|

General Curtis M. Scaparrotti | 2 October 2013 | 30 April 2016 |

|

General Vincent K. Brooks | 30 April 2016 | Present |

History

The following is a partial list of border incidents involving North Korea since the Armistice Agreement of 27 July 1953, ended large scale military action of the Korean War. Most of these incidents took place near either the Korean Demilitarized Zone or the Northern Limit Line. This list includes engagements on land, air, and sea, but does not include alleged incursions and terrorist incidents that occurred away from the border.

Many of the incidents occurring at sea are due to border disputes. The North claims jurisdiction over a large area south of the disputed western maritime border, the Northern Limit Line in the waters west of the Korean Peninsula. This is a prime fishing area, particularly for crabs, and clashes commonly occur. In addition, the North claims its territorial waters extend for 50 nautical miles (90 km) from the coast, rather than the 12 nautical miles (22 km) recognized by other countries. According to the 5 January 2011 Korea Herald, since July 1953 North Korea has violated the armistice 221 times, including 26 military attacks.[1]

1950s

- 16 February 1958: North Korean agents hijack a South Korean airliner to Pyongyang en route from Pusan to Seoul; 1 American pilot, 1 American passenger, 2 West German passengers, and 24 other passengers were released in early March, but 8 other passengers remained in the North.[2]

1960s

- May 1962: Private Larry Allen Abshier abandoned his post in South Korea in May 1962 when he crept away from his base and crossed the DMZ into North Korea. Larry Abshier was the first to defect. Also in May 1962, Corporal Jerry Parrish crossed the DMZ into North Korea. His reasons for defecting, according to Jenkins' autobiography The Reluctant Communist, were "personal, and [Parrish] didn't elaborate about them much except to say that if he ever went home, his father-in-law would kill him."[3]

- Aug 1962: James Joseph Dresnok was a Private First Class with a U.S. Army unit along the Korean Demilitarized Zone. Soon after his arrival, he found himself facing a court martial for forging signatures on paperwork that gave him permission to leave base and which, ultimately, led to him being AWOL (Absent Without Official Leave).[4] Unwilling to face punishment, on 15 August 1962, while his fellow soldiers were eating lunch, he ran across a minefield in broad daylight into North Korean territory, where he was quickly apprehended by North Korean soldiers. Dresnok was taken by train to Pyongyang, the North Korean capital, and interrogated.[5]

- 1964: North Korea creates an underground group: Revolution Party for Reunification, this group is ground down and eliminated by South Korean authorities by 1969 [6]

- Jan 1965: Charles Jenkins, the most notable case, defected to North Korea. In South Korea, Jenkins was assigned to night patrols. As a result of fears that he would be transferred to combat duty in Vietnam, he grew depressed and anxious, and started drinking alcohol. On the night of 4 January 1965, after reportedly drinking ten beers, he set off on his nightly patrol of the Demilitarized Zone. In the early morning, he told his patrol that he was going to investigate a noise.[7] He subsequently crossed into North Korea and surrendered to forces there, in hopes of being sent to Russia and then, through prisoner exchange, eventually returned to America. Shortly thereafter, North Korean propaganda declared that a U.S. sergeant had defected, and broadcast statements allegedly made by the defector, reportedly in stilted English. The U.S. Army claimed Jenkins wrote four letters stating his intention to defect (an allegation Jenkins denies); however, the original letters are reportedly lost. His relatives maintained throughout his absence that he was abducted.[7]

- 27 April 1965: Two North Korean MiG-17s attack a United States EC-121 Warning Star reconnaissance plane in the waters east of the Korean Peninsula, 80 km (50 mi) from the North Korean shore. The aircraft was damaged, but managed to land at Yokota Air Base, Japan.[8][9]

- 17 January 1968: In an incident known as the Blue House Raid, a 31-man detachment from the Korean People's Army secretly crosses the DMZ on a mission to kill South Korean President Park Chung-hee on 21 January, nearly succeeding. The incursion was discovered after South Korean civilians confronted the North Koreans and informed the authorities. After entering Seoul disguised as South Korean soldiers, the North Koreans attempt to enter the Blue House (the official residence of the President of South Korea). The North Koreans are confronted by South Korean police and a firefight ensued. The North Koreans fled Seoul and individually attempted to cross the DMZ back to North Korea. Of the original group of 31 North Koreans, 28 were killed, one was captured, and two are unaccounted for. Additionally, 68 South Koreans were killed and 66 were wounded, the majority of whom were soldiers and police officers. Three American soldiers were also killed and three were wounded.[10]

- 23 January 1968: The United States Naval ship the USS Pueblo is boarded and captured, along with its crew, by North Korean forces in the waters east of the Korean Peninsula. The entire crew of 83 is captured, with the exception of one sailor killed in the initial attack on the vessel, and the vessel was taken to a North Korean port. All the captives were released on 23 December of the same year via the Bridge of No Return at the DMZ. The USS Pueblo is still in North Korean possession and is docked in Pyongyang and is on display as a museum ship.[11]

- 30 October 1968: From 30 October – 2 November 120 to 130 North Korean commandos land on the northeast shore of South Korea, allegedly to establish a base in order to wage a guerrilla war against the South Korean government. A total of 110 to 113 were killed, seven were captured, and 13 escaped. Around 20 South Korean civilians, law enforcement officers, and soldiers were killed.[9][12]

- March 1969: Six North Korean commandos kill a South Korean police officer near Jumunjin, Gangwon-do. Seven American soldiers are killed in a North Korean attack along the DMZ.[13]

- April 1969: An EC-121, U.S. reconnaissance plane is shot down 90 miles (140 km) east of the North Korean coast, leaving 31 dead.

- November 1969: Four U.S. soldiers are killed by North Koreans in the Demilitarized Zone.

1970s

- April 1970: In Geumchon, a region of Paju south of the DMZ, a clash leaves three North Korean soldiers dead and five South Korean soldiers wounded.

- June 1970: The North Korean navy seizes a broadcast vessel from the South near the Northern Limit Line. 20 crew are captured.

- February 1974: Two South Korean fishing vessels are sunk and 30 crew detained by the North.

- 1974: The first tunnel into ROK is discovered (the three following tunnels were found in 1975, 1978, 1990)[6]

- June 1976: An incursion south of the DMZ in Gangwon-do leaves three dead from the North and six from the South.

- 18 August 1976: The Axe murder incident—an attempt to clear brush in the Demilitarized Zone near Panmunjom ends with two U.S. soldiers dead.

- October 1979: Three North Koreans enter the eastern DMZ. One is killed.

- December 1979: One U.S. Army soldier killed, 3 U.S. soldiers wounded after stumbling into a North Korean minefield in a heavy fog while patrolling DMZ. One body is recovered from the North Koreans 5 days later.

1980s

- March 1980: Three North Koreans are killed while trying to cross the Han River estuary.

- May 1980: North Koreans engage OP Ouillette on DMZ in firefight. One North Korean WIA.

- March 1981: Three North Koreans try to enter the South in Geumhwa-eup, Cheorwon, Gangwon-do; one is killed.

- July 1981: Three North Koreans are killed trying to cross the Imjin River to the South.

- November 1984: Nine North Korean soldiers and one South Korean soldier die, and one American soldier is wounded during the firefight that erupted when a North Korean security detail chased a defecting Soviet citizen (Vasily Matusak) across the MDL into the southern-controlled sector of the Joint Security Area.

- November 1987: One South Korean killed on DMZ central sector by North Korean sniper fire.

1990s

- May 1992: Three Northern soldiers in South Korean uniforms are killed in Cheolwon, Gangwon-do; three South Korean soldiers are wounded.

- December 1994: North Koreans shoot down US Army helicopter. One US KIA and one US POW for 13 days.

- May 1995: North Korean forces fire on a South Korean fishing boat, killing three.

- October 1995: Two armed North Koreans are discovered at the Imjin River; one is killed.

- April 1996: Several hundred armed North Korean troops cross repeatedly into the Demilitarized Zone.

- May 1996: Seven Northern soldiers cross south of the Demilitarized Zone, but withdraw after warning shots are fired.

- May & June 1996: North Korean vessels twice cross the Northern Limit Line and have a several-hour standoff with the South Korean navy.

- April 1997: Five North Korean soldiers cross the Demilitarized Zone in Cheolwon, Gangwon-do, and fire on South Korean positions.

- June 1997: Three North Korean vessels cross the Northern Limit Line and attack South Korean vessels two miles (3 km) south of the line. On land, fourteen North Korean soldiers cross 70 m south of the center of the DMZ, leading to a 23-minute exchange of fire.

- June 1999: A series of clashes between North and South Korean vessels take place in the waters west of the Korean Peninsula near the Northern Limit Line.

2000s

- 2001: On twelve separate occasions, North Korean vessels cross the Northern Limit Line and then withdraw.

- 27 November 2001: North and South Korean forces exchange fire without injuries.

- 29 June 2002: Renewed naval clashes near the Northern Limit Line lead to the deaths of four South Korean sailors and the sinking of a South Korean vessel. The number of North Koreans killed is unknown.

- 16 November 2002: South Korean forces fire warning shots on a Northern boat crossing the Northern Limit Line. The boat withdraws. The similar incident is repeated on 20 November.

- 19 February 2003: A North Korean fighter plane crosses seven miles (11 km) south of the Northern Limit Line, and returns north after being intercepted by six South Korean planes.

- 2 March 2003: Four North Korean fighter jets intercept a US reconnaissance plane over the waters east of the Korean Peninsula.

- 17 July 2003: North and South Korean forces exchange fire at the DMZ around 6 AM. The South Korean army reports four rounds fired from the North and seventeen from the South. No injuries are reported.[14]

- 1 November 2004: North Korean vessels, claiming to be in pursuit of illegal fishing craft, cross the Northern Limit Line and are fired upon by the South. The vessels withdraw 3 hours later.

- 30 July 2006: Several rounds are exchanged near a South Korean post in Yanggu, Gangwon.

| Wikinews has related news: Korean navies exchange fire |

- 10 November 2009: Naval vessels from the two Koreas exchanged fire in the area of the NLL, reportedly causing serious damage to a North Korean patrol ship.[15] For more details of this incident, see Battle of Daecheong.

2010s

- 26 March 2010: A South Korean naval vessel, the ROKS Cheonan, was allegedly sunk by a North Korean torpedo near Baengnyeong Island in the waters west of the Korean Peninsula. A rescue operation recovered 58 survivors but 46 sailors were killed. On 20 May 2010, a South Korean led international investigation group concluded that the sinking of the warship was in fact the result of a North Korean torpedo attack.[16][17] North Korea denied involvement.[18] The United Nations Security Council made a Presidential Statement condemning the attack but without identifying the attacker.[19]

- 23 November 2010: North Korea fired artillery at South Korea's Greater Yeonpyeong island in the waters west of the Korean Peninsula and South Korea returned fire. Two South Korean marines and two South Korean civilians were killed, six were seriously wounded, and ten were treated for minor injuries. Approximately seventy South Korean houses were destroyed.[20][21][22] North Korean casualties were unknown, but Lee Hong-gi, the Director of Operations of the South Korean Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), claimed that as a result of the South Korean retaliation "there may be a considerable number of North Korean casualties".[23]

- 2014: Some of the American forces that had been lost with troops moved to invade Iraq have been replaced by the nine-month-long deployment of a battalion from the First Cavalry Division.[24]

Number of U.S. soldiers stationed in South Korea by year

| Year | Number |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 510 |

| 1951 | 326,863 |

| 1952 | 326,863 |

| 1953 | 326,863 |

| 1954 | 225,590 |

| 1955 | 75,328 |

| 1956 | 68,813 |

| 1957 | 71,045 |

| 1958 | 46,024 |

| 1959 | 49,827 |

| 1960 | 55,864 |

| 1961 | 57,694 |

| 1962 | 60,947 |

| 1963 | 56,910 |

| 1964 | 62,596 |

| 1965 | 58,636 |

| 1966 | 47,076 |

| 1967 | 55,057 |

| 1968 | 62,263 |

| 1969 | 66,531 |

| 1970 | 52,197 |

| 1971 | 40,740 |

| 1972 | 41,600 |

| 1973 | 41,864 |

| 1974 | 40,387 |

| 1975 | 40,204 |

| 1976 | 39,133 |

| 1977 | 40,705 |

| 1978 | 41,565 |

| 1979 | 39,018 |

| 1980 | 38,780 |

| 1981 | 38,254 |

| 1982 | 39,194 |

| 1983 | 38,705 |

| 1984 | 40,785 |

| 1985 | 41,718 |

| 1986 | 43,133 |

| 1987 | 44,674 |

| 1988 | 45,501 |

| 1989 | 44,461 |

| 1990 | 41,344 |

| 1991 | 40,062 |

| 1992 | 35,743 |

| 1993 | 34,830 |

| 1994 | 36,796 |

| 1995 | 36,016 |

| 1996 | 36,539 |

| 1997 | 35,663 |

| 1998 | 36,890 |

| 1999 | 35,913 |

| 2000 | 36,565 |

| 2001 | 37,605 |

| 2002 | 37,743 |

| 2003 | 41,145 |

| 2004 | 40,840 |

| 2005 | 30,983 |

| 2006 | 28,500 |

| 2007 | 28,500 |

| 2008 | 28,500 |

| 2009 | 28,500 |

| 2010 | 28,500 |

| 2011 | 28,500 |

| 2012 | 28,500 |

| 2013 | 28,500 |

| 2014 | 29,300 |

Controversy

Gwangju Uprising

The 1980s marked a surge in anti-Americanism in Korea, widely traced to the events of May 1980.[26]

Gwangju convinced a new generation of young [Koreans] that the democratic movement had developed not with the support of Washington, as an older generation of more conservative Koreans thought, but in the face of daily American support for any dictator who could quell the democratic aspirations of the Korean people. The result was an anti-American movement in the 1980s that threatened to bring down the whole structure of American support for the ROK. American cultural centers were burned to the ground (more than once in Gwangju); students immolated themselves in protest of Reagan's support for Chun.[27]

Fundamental to this movement was a perception of U.S. complicity in Chun's rise to power, and, more particularly, in the Gwangju massacre itself. These matters remain controversial. It is clear, for example, that the U.S. authorized the Korean Army's 20th Division to re-take Gwangju – as acknowledged in a 1982 letter to the New York Times by then-Ambassador Gleysteen.

[General Wickham], with my concurrence, permitted transfer of well-trained troops of the twentieth R.O.K.A. Division from martial-law duty in Seoul to Gwangju because law and order had to be restored in a situation that had run amok following the outrageous behavior of the Korean Special Forces, which had never been under General Wickham's command.[28]

However, as Gwangju Uprising editors Scott-Stokes and Lee note, whether the expulsion of government troops left the situation lawless or "amok" is very much open to dispute.

21st century

In 2002, anti-American sentiment in South Korea spiked after two U.S. soldiers in an M60 AVLB armoured vehicle-launched bridge accidentally hit and killed two South Korean teenage girls in the Yangju highway incident.[29]

An expansion of Camp Humphreys later in the decade saw protests, drawing thousands of South Korean citizens,[30] resulting in occasional violent clashes and arrests.[31] Following a series of large protests against the U.S. and Republic of Korea governments' plan to expand Camp Humphreys and make it the main base for most U.S. troops in South Korea, residents of Daechuri and other small villages near Pyeongtaek agreed to a government settlement to leave their homes in 2006 and allow the base's expansion.[32][33] Compensation for the land averaged 600 million won (about 600,000 USD) per resident.[34]

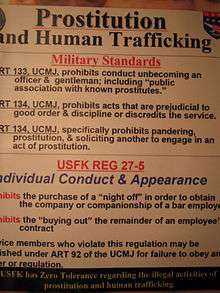

Relationships between U.S. soldiers and South Korean women

Western princesses (prostitutes servicing U.S. soldiers) have resulted in a negative image for South Korean women who have relationships with American men.[35][36]

Exercises

Each year the ROK, the US and a selection of Sending States from the United Nations Command participate in multiple defense-oriented, combined and joint training events designed to defend the Republic of Korea, protect the region, and maintain and increase stability on the Korean peninsula.

Ulchi-Freedom Guardian, Key Resolve, and Foal Eagle, in addition to multiple Rehearsal of Concept (ROC) Drills, are the three theater level exercises.

- Ulchi-Freedom Guardian (UFG) is an annual simulation driven, command transformation-oriented Command Post Exercise (CPX). Elements of the ROK and US governments participate, as well as ROK and US forces from on and off the Korean peninsula. UFG integrates the annual ROK government exercise "Ulchi", which focuses on procedures for transitioning to war, government support. Ulchi also emphasizes ROK procedures for coordination between government and military organizations from the national to local level. UFG typically incorporates the following components: a Crisis Management Exercise focused on strategic and operational decisions needed to defuse a crisis, or posture the command for successful execution of the appropriate OPLAN if the enemy actions dictate; a Senior Leader Seminar (SLS) designed to foster senior-level discussion on a variety of topics related to crisis management and war-fighting; and a two-week Computer Assisted Exercise that exercises the transition to war, defense, and counteroffensive phases of the war-fight. The exercise culminates in detailed senior leader level After-Action Reviews (AARs).

- Key Resolve (KR) is over the course of a two-week-long CFC and ROK crisis management and war-fighting exercise. It provides invaluable opportunities to evaluate, train, and improves combined and joint coordination, procedures, plans and systems necessary for the conduct of contingency operations by ROK and US forces. It is a simulation driven Command Post exercise that exercises the defense of the ROK and the ability of the US to bring forces into the Theater of Operations to participate in that defense. The exercise culminates in detailed senior leader level AARs.

- Foal Eagle (FE) is a series of component-sponsored joint and combined Field Training Exercises (FTX) that support training of OPLAN related tasks via participation of selected off-peninsula units. FE demonstrates US power projection and rapid deployment capabilities and is conducted concurrently, but not linked to, the KR CPX. Tactical units are the primary FE FTX training audience exercising all aspects of CFC's mission; rear area security, support operations, RSOI, special operations, ground maneuver, expeditionary operations, air combat operations, and maritime operations.

Shoulder sleeve insignia

Description

A shield-shaped embroidered device 3 1/8 inches (7.94 cm) in height and 2 1/2 inches (6.35 cm) in width overall blazoned: azure, in chief four mullets bendwise argent, all above a stylized American bald eagle, issuant from sinister base volant to dexter chief; the eagle’s body gules surmounted by two bendlets, wider at base, of the second throughout; head of the second, eyed of the field, leg and talons of the second grasping a laurel branch and seven arrows or. The entire shield shape is edged with a 1/16 inch(.16 cm) white border. Attached above the device is a designation band in scarlet inscribed "USFK" in white letters. The entire device is edged with a 1/8 inch (.32 cm) blue border.

Symbolism

The shield shape reflects the United States Forces Korea’s steadfast commitment to defend the sovereignty of South Korea. The abbreviation "USFK" stands for United States Forces Korea which activated on 1 July 1957. The four stars symbolize the service and contributions of the United States Army, United States Navy, United States Air Force, and the United States Marine Corps. The stylized American bald eagle represents cohesion and unity among the services. The laurel sprigs and arrows depict the mission of the United States Forces Korea to defeat aggression if necessary. Red, white, and blue are the colors of the flag of the United States of America. Red symbolizes hard work and honor, white represents innocence and purity, and blue refers to justice and perseverance. Yellow signifies wisdom and intuition.

Background

The shoulder sleeve insignia was approved on 18 June 2012. (TIOH Dwg. No. A-1-1077).[37]

See also

- Military of South Korea

- Military of North Korea

- KATUSA (Korean Augmentation to US Army)

- United States Forces Japan (USFJ)

- List of United States Army installations in South Korea

- U.S.–South Korea Status of Forces Agreement

- United States Army Military Government in Korea (1945–1948)

- Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of Korea

- Aftermath of the Korean War

- Division of Korea

- 38th parallel north

References

- ↑ "N.K. Commits 221 Provocations Since 1953". Korea Herald. 5 January 2011.

- ↑ Dick K. Nanto (18 March 2003). "Report for Congress, North Korea: Chronology of Provocations, 1950 - 2003" (PDF). Federation for American Scientists. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ↑ The Reluctant Communist. Charles Robert Jenkins (University of California Press) p. 34

- ↑ Russell, Mark (19 October 2006), An American in North Korea, Pledging Allegiance to the Great Leader, New York Times, retrieved 28 January 2007

- ↑ Anderson, Robert G.; Casey Morgan (28 January 2007). "Joe Dresnok: An American In North Korea". 60 Minutes. CBS News. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- 1 2 Seth, Michael. "12 North Korea: Recovery, Transformation, and Decline, 1953 to 1993". A History of Korea: History to Antiquity. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- 1 2 "Deserter Recalls N. Korean Hell". CBS News.

- ↑ "Cold War Shootdowns". Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- 1 2 "North Korean Provocative Actions, 1950 - 2007" (PDF). United States Congress. 2007-04-20. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ Daniel, Bolger. "3: A Continuous Nightmare" (PDF). Scenes from an Unfinished War: Low-Intensity Conflict in Korea, 1966-1968 (PDF). Command and General Staff College. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ "Pueblo". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. United States Navy. Archived from the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ "filtration of North Korean Commando Troops into Ulchin-Samchok Area". Koreascope. 2006-08-31. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- ↑ "7 GIs Die in Korean DMZ Fighting". The Hartford Courant. 17 March 1969.

- ↑ "North, South Trade Fire Along DMZ". VOA News. Archived from the original on 2007-10-26. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- ↑ Kim, San (10 November 2009). Koreas clash in the waters west of the Korean Peninsula, blame each other. Yonhap.

- ↑ Foster, Peter; Moore, Malcolm (20 May 2010). "North Korea condemned by world powers over torpedo attack". London: Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ Park In-kook (4 June 2010), "Letter dated 4 June 2010 from the Permanent Representative of the Republic of Korea to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council" (PDF), United Nations Security Council, S/2010/281, retrieved 11 July 2010

- ↑ "Press Conference on Situation in Korean Peninsula: DPRK Permanent Representative to the United Nations Sin Son Ho". Department of Public Information. United Nations. 15 June 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ "Presidential Statement: Attack on Republic of Korea Naval Ship 'Cheonan'". United Nations Security Council. United Nations. 9 July 2010. S/PRST/2010/13. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ "북한 해안포 도발 감행, 연평도에 포탄 100여발 떨어져". Chosun Ilbo. 23 November 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-23.

- ↑ "GLOBAL MARKETS: European Stocks Seen Lower On Korea News". The Wall Street Journal. 23 November 2010.

- ↑ Gabbatt, Adam (23 November 2010). "North Korea fires on South Korea – live coverage". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ Gwon, Seung-jun (23 November 2010). "합참 "우리 군 대응사격으로 북한 측 피해도 상당할 것"". The Chosun Ilbo. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ↑ SHANKER, THOM (7 January 2014). "Additional U.S. Battalion Going to South Korea". www.nytimes.com. New York Times. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ↑ Christine Ahn; Hyun Lee (21 October 2011). "Number of US Troops in South Korea". NZ-DPRKSociety. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ↑ http://www.eroseffect.com/articles/neoliberalismgwangju.htm#_ednref71 Neoliberalism and the Gwangju Uprising

- ↑ Bruce Cumings in Lee Jai-Eui, Gwangju Diary. University of California, 1999. p. 27

- ↑ quoted in The Gwangju Uprising. Ed. Henry Scott-Stokes and Lee Jai-Eui, East Gate Publishing, 2000. p. 231

- ↑ "Anti-US protests grow in Seoul". BBC News. 8 December 2002. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ Franklin Fisher (13 May 2006). "Turmoil, barbed wire surround rice fields". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "Ten injured in protest near U.S. military base". Joongang Daily. 8 August 2005. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "Ceremonies honor residents driven from lands slated for Humphreys expansion". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 9 April 2007.

- ↑ "S. Koreans rally at Camp Humphreys fence to protest U.S. presence". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 10 August 2005.

- ↑ "Daechuri issue sees no resolve". The Hankyoreh. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Sung So-young (2012-06-13). "The actual reality of interracial relationships". Joongang Daily. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- ↑ Kim, Soe-jung (2005-10-23). "Forum tackles overseas marriages". Joongang Daily. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

- ↑ The Institute of Heraldry, http://www.tioh.hqda.pentagon.mil/Heraldry/ArmyDUISSICOA/ArmyHeraldryUnit.aspx?u=8572

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States Forces Korea. |

- United States Forces Korea (USFK) official website

- U.S. Forces, Korea / ROK-US Combined Forces Command (globalsecurity.org)

- U.S. Naval Forces Korea official website

- 8th Fighter Wing, Kusan Air Base official website

- 51st Fighter Wing, Osan Air Base official website

- "Northern Limit Line (NLL) West Sea Naval Engagements". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2006-08-01.

- Nanto, D.K. (2003-03-18). "North Korea: A Chronology of Provocations, 1950-2003" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-08-01.