Georgian scripts

| Georgian | |

|---|---|

|

damts'erloba "script" in Mkhedruli | |

| Type | |

| Languages | Georgian (originally) and other Kartvelian languages |

Time period |

430[1] – present

or

|

Parent systems |

Modelled on Greek

|

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 |

Geor, 240 – Georgian (Mkhedruli) Geok, 241 – Khutsuri (Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri) |

Unicode alias | Georgian |

| |

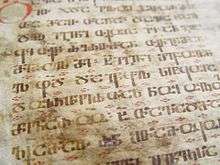

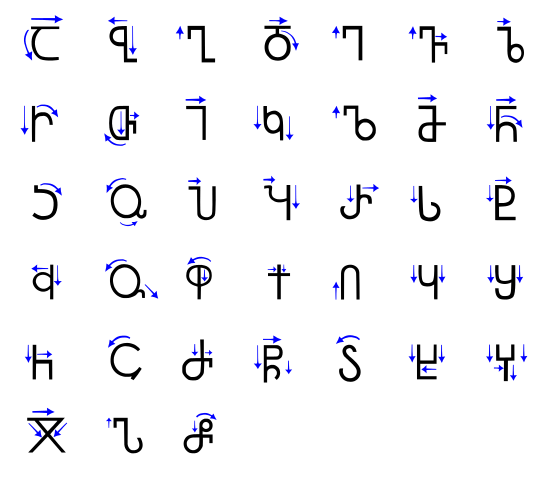

The Georgian scripts are the three writing systems used to write the Georgian language: Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri and Mkhedruli. Although the systems differ in appearance, all three are unicase, their letters share the same names and alphabetical order, and are written horizontally from left to right. Of the three scripts, Mkhedruli was the civilian royal script of the Kingdom of Georgia mostly used for the royal charters. Mkhedruli is the standard script for modern Georgian and its related Kartvelian languages, whereas Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri are used only in ceremonial religious texts and iconography.[2]

Georgian scripts are unique in their appearance and their exact origin has never been established; however, in strictly structural terms, their alphabetical order largely corresponds to the Greek alphabet, with the exception of letters denoting uniquely Georgian sounds, which are grouped at the end.[3][4] Originally consisting of 38 letters,[5] Georgian is presently written in a 33-letter alphabet, as five letters are currently obsolete in that language. The number of Georgian letters used in other Kartvelian languages varies. The Mingrelian language uses 36, 33 of which are current Georgian letters, one obsolete Georgian letter, and two additional letters specific to Mingrelian and Svan. That same obsolete letter, plus a letter borrowed from Greek (making 35 letters total), are used in writing the Laz language. The fourth Kartvelian language, Svan, is not commonly written, but when it is, it uses Georgian letters as utilized in Mingrelian, with an additional obsolete Georgian letter and sometimes supplemented by diacritics for its many vowels.[2][6]

Georgian scripts were granted the national status of cultural heritage in Georgia in 2015[7] and inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016.[8]

Preview

Origins

The origins of the Georgian script are to this date poorly known, and no full agreement exists among Georgian and foreign scholars as to its date of creation, who designed the script and the main influences on that process.

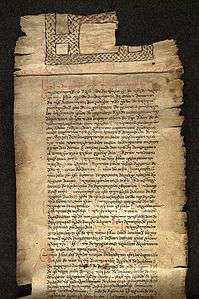

The first version of the script attested is Asomtavruli which dates back to at least the 5th century; the other scripts were formed in the following centuries. Most scholars link the creation of the Georgian alphabet to the process of Christianisation of a core Georgian-speaking kingdom, that is, Kartli (or Iberia in Classical sources).[9] The alphabet was therefore most probably created between the conversion of Iberia under King Mirian III (326 or 337) and the Bir el Qutt inscriptions of 430,[10] contemporaneously with the Armenian alphabet.[11] It was first used for translation of the Bible and other Christian literature into Georgian, by monks in Georgia and Palestine.[4] Professor Levan Chilashvili's dating of fragmented Asomtavruli inscriptions, discovered by him at the ruined town of Nekresi, in Georgia's easternmost province of Kakheti, in the 1980s, to the 1st or 2nd century has not been accepted.[12]

A Georgian tradition first attested in the medieval chronicle Lives of the Kings of Kartli (ca. 800),[4] assigns a much earlier, pre-Christian origin to the Georgian alphabet, and names King Pharnavaz I (3rd century BC) as its inventor. This account is now considered legendary, and is rejected by scholarly consensus, as no archaeological confirmation has been found.[4][13][14] Rapp considers the tradition to be an attempt by the Georgian Church to rebut the earlier tradition that the alphabet was invented by Mesrop Mashtots, and is a Georgian application of an Iranian model in which primordial kings are credited with the creation of basic social institutions. [15] Georgian linguist Tamaz Gamkrelidze offers an alternate interpretation of the tradition, in the pre-Christian use of foreign scripts (alloglottography in the Aramaic alphabet) to write down Georgian texts.[16]

A point of contention among scholars is the role played by Armenian clerics in that process. According to a number of scholars and medieval Armenian sources, Mesrop Mashtots, generally acknowledged as the creator of the Armenian alphabet, also created the Georgian and Caucasian Albanian alphabets. This tradition originates in the works of Koryun, a fifth century historian and biographer of Mashtots,[17] and has been quoted by Donald Rayfield and James R. Russell,[13][18] but has been criticized by scholars, both Georgian[19] and Western,[4] who judge the passage in Koryun unreliable or even a later interpolation. Other scholars quote Koryun's claims without taking a stance on its validity.[20][21] Many agree, however, that Armenian clerics, if not Mashtots himself, must have played a role in the creation of the Georgian script.[4][14][22]

Another controversy regards the main influences at play in the Georgian alphabet, as scholars have debated whether it was inspired more by the Greek alphabet, or by Semitic alphabets such as Aramaic.[16] Recent historiography focuses on greater similarities with the Greek alphabet than in the other Caucasian writing systems, most notably the order and numeric value of letters.[3][4] Some scholars have also suggested as a possible inspiration for particular letters certain pre-Christian Georgian cultural symbols or clan markers.[23]

Asomtavruli

Asomtavruli (Georgian: ასომთავრული) is the oldest Georgian script. The name Asomtavruli means "capital letters", from aso (ასო) "letter" and mtavari (მთავარი) "principal/head". It is also known as Mrgvlovani (Georgian: მრგვლოვანი) "rounded", from mrgvali (მრგვალი) "round", so named because of its round letter shapes. Despite its name, this "capital" script is unicameral, just like the modern Georgian script, Mkhedruli.[24]

The oldest Asomtavruli inscriptions found so far date from the 5th century[25] and are Bir el Qutt[26] and the Bolnisi inscriptions.[27]

From the 9th century, Nuskhuri script starting becoming dominant, and the role of Asomtavruli was reduced. However, epigraphic monuments of the 10th to 18th centuries continued to be written in Asomtavruli script. Asomtavruli in this later period became more decorative. In the majority of 9th-century Georgian manuscripts which were written in Nuskhuri script, Asomtavruli was used for titles and the first letters of chapters.[28] Although, some manuscripts written completely in Asomtavruli can be found until the 11th century.[29]

Form of Asomtavruli letters

In early Asomtavruli, the letters are of equal height. Georgian historian and philologist Pavle Ingorokva believes that the direction of Asomtavruli, like that of Greek, was initially boustrophedon, though the direction of the earliest surviving texts is from left to the right.[30]

In most Asomtavruli letters, straight lines are horizontal or vertical and meet at right angles. The only letter with acute angles is Ⴟ (ჯ jani). There have been various attempts to explain this exception. Georgian linguist and art historian Helen Machavariani believes jani derives from a monogram of Christ, composed of the Ⴈ (ი ini) and Ⴕ (ქ kani).[31] According to Georgian scholar Ramaz Pataridze, the cross-like shape of letter jani indicates the end of the alphabet, and has the same function as the similarly shaped Phoenician letter taw (![]() ), Greek chi (Χ), and Latin X,[32] though these letters do not have that function in Phoenician, Greek, or Latin.

), Greek chi (Χ), and Latin X,[32] though these letters do not have that function in Phoenician, Greek, or Latin.

Coins of Queen Tamar of Georgia and King George IV of Georgia minted using Asomtavruli script, 1200–1210 AD.

From the 7th century, the forms of some letters began to change. The equal height of the letters was abandoned, with letters acquiring ascenders and descenders.[33][34]

| Ⴀ ani |

Ⴁ bani |

Ⴂ gani |

Ⴃ doni |

Ⴄ eni |

Ⴅ vini |

Ⴆ zeni |

Ⴡ he |

Ⴇ tani |

Ⴈ ini |

Ⴉ k'ani |

Ⴊ lasi |

Ⴋ mani |

Ⴌ nari |

Ⴢ hie |

Ⴍ oni |

Ⴎ p'ari |

Ⴏ zhani |

Ⴐ rae |

| Ⴑ sani |

Ⴒ t'ari |

Ⴣ vie |

ႭჃ Ⴓ uni |

Ⴔ pari |

Ⴕ kani |

Ⴖ ghani |

Ⴗ q'ari |

Ⴘ shini |

Ⴙ chini |

Ⴚ tsani |

Ⴛ dzili |

Ⴜ ts'ili |

Ⴝ ch'ari |

Ⴞ khani |

Ⴤ qari |

Ⴟ jani |

Ⴠ hae |

Ⴥ hoe |

- Note: Some fonts show "capitalized" (tall) variants of Nuskhuri and Mkhedruli letters rather than Asomtavruli.

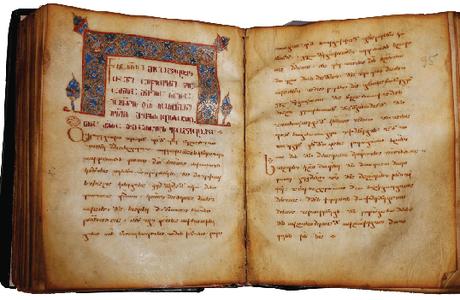

Asomtavruli illumination

In Nuskhuri manuscripts, Asomtavruli are used for titles and illuminated capitals. The latter were used at the beginnings of paragraphs which started new sections of text. In the early stages of the development of Nuskhuri texts, Asomtavruli letters were not elaborate and were distinguished principally by size and sometimes by being written in cinnabar ink. Later, from the 10th century, the letters were illuminated. The style of Asomtavruli capitals can be used to identify the era of a text. For example, in the Georgian manuscripts of the Byzantine era, when the styles of the Byzantine Empire influenced Kingdom of Georgia, capitals were illuminated with images of birds and other animals.[35]

.png)

.png)

Decorative Asomtavruli capital letters, მ (m), ნ (n) and თ (t), 12–13th century.

From the 11th-century "limb-flowery", "limb-arrowy" and "limb-spotty" decorative forms of Asomtavruli are developed. The first two are found in 11th- and 12th-century monuments, whereas the third one is used until the 18th century.[36][37]

Importance was attached also to the colour of the ink itself.[38]

Asomtavruli letter დ (doni) is often written with decoration effects of fish and birds.[39]

The "Curly" decorative form of Asomtavruli is also used where the letters are wattled or intermingled on each other, or the smaller letters are written inside other letters. It was mostly used for the headlines of the manuscripts or the books, although there are compete inscriptions which were written in the Asomtavruli "Curly" form only.[40]

The title of Gospel of Matthew in Asomtavruli "Curly" decorative form.

Handwriting of Asomtavruli

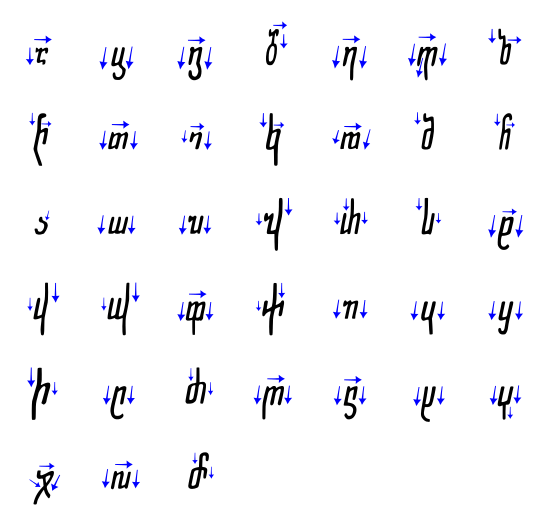

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Asomtavruli letter:[41]

Nuskhuri

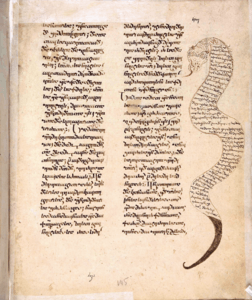

Nuskhuri (Georgian: ნუსხური) is the second Georgian script. The name nuskhuri comes from nuskha (ნუსხა), meaning "inventory" or "schedule". Nuskhuri was soon augmented with Asomtavruli illuminated capitals in religious manuscripts. The combination is called Khutsuri (Georgian: ხუცური, "clerical", from khutsesi (ხუცესი "cleric"), and it was principally used in hagiography.[42]

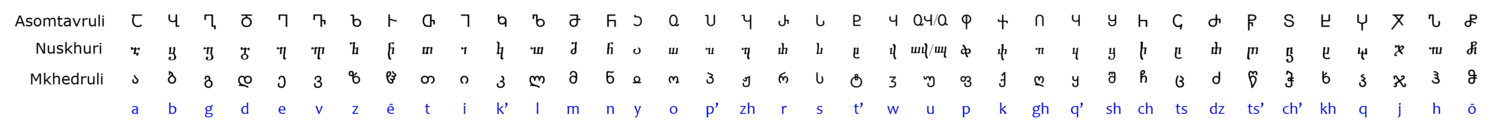

Nuskhuri first appeared in the 9th century as a graphic variant of Asomtavruli.[43] The oldest inscription is found in the Ateni Sioni Church and dates to 835 AD.[44] The oldest surviving Nuskhuri manuscripts date to 864 AD.[45] Nuskhuri becomes dominant over Asomtavruli from the 10th century.[42]

Form of Nuskhuri letters

Nuskhuri letters vary in height, with ascenders and descenders, and are slanted to the right. Letters have an angular shape, with a noticeable tendency to simplify the shapes they had in Asomtavruli. This enabled faster writing of manuscripts.[46]

Asomtavruli letters ო (oni) and ჳ (vie). A ligature of these letters produced a new letter in Nuskhuri, უ uni.

| ⴀ ani |

ⴁ bani |

ⴂ gani |

ⴃ doni |

ⴄ eni |

ⴅ vini |

ⴆ zeni |

ⴡ he |

ⴇ tani |

ⴈ ini |

ⴉ k'ani |

ⴊ lasi |

ⴋ mani |

ⴌ nari |

ⴢ hie |

ⴍ oni |

ⴎ p'ari |

ⴏ zhani |

ⴐ rae |

| ⴑ sani |

ⴒ t'ari |

ⴣ vie |

ⴍⴣ ⴓ uni |

ⴔ pari |

ⴕ kani |

ⴖ ghani |

ⴗ q'ari |

ⴘ shini |

ⴙ chini |

ⴚ tsani |

ⴛ dzili |

ⴜ ts'ili |

ⴝ ch'ari |

ⴞ khani |

ⴤ qari |

ⴟ jani |

ⴠ hae |

ⴥ hoe |

- Note: Without proper font support, you may see question marks, boxes or other symbols instead of Nuskhuri letters.

Handwriting of Nuskhuri

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Nuskhuri letter:[47]

Use of Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri today

Asomtavruli is used intensively in iconography, murals, and exterior design, especially in stone engravings.[48] Georgian linguist Akaki Shanidze made an attempt in the 1950s to introduce Asomtavruli into the Mkhedruli script as capital letters to begin sentences, as in the Latin script, but it didn't catch on.[49][50] Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri are officially used by the Georgian Orthodox Church alongside Mkhedruli. Patriarch Ilia II of Georgia called on people to use all three Georgian scripts.[51]

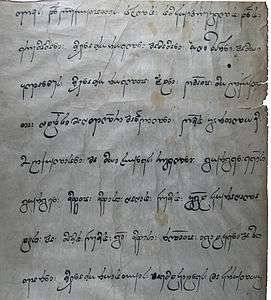

Mkhedruli

Mkhedruli (Georgian: მხედრული) is the third and current Georgian script. Mkhedruli, literally meaning "cavalry" or "military", derives from mkhedari (მხედარი) meaning "horseman", "knight", "warrior"[52] and "cavalier".[53]

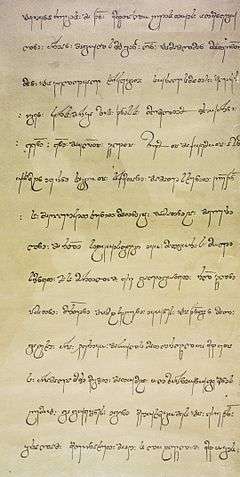

Like the two other scripts, Mkhedruli is purely unicameral. Mkhedruli first appears in the 10th century. The oldest Mkhedruli inscription is found in Ateni Sioni Church dating back to 982 AD. The second oldest Mkhedruli-written text is found in the 11th-century royal charters of King Bagrat IV of Georgia. Mkhedruli was mostly used then in the Kingdom of Georgia for the royal charters, historical documents, manuscripts and inscriptions.[54] Mkhedruli was used for non-religious purposes only and represented the "civil", "royal" and "secular" script.[55][56]

Mkhedruli became more and more dominant over the two other scripts, though Khutsuri (Nuskhuri with Asomtavruli) was used until the 19th century. Since the 19th century, with the establishment and development of the printed Georgian fonts, Mkhedruli became universal writing Georgian outside the Church.[57]

Form of Mkhedruli letters

Mkhedruli inscriptions of the 10th and 11th centuries are characterized in rounding of angular shapes of Nuskhuri letters and making the complete outlines in all of its letters. Mkhedruli letters are written in the four-linear system, similar to Nuskhuri. Mkhedruli becomes more round and free in writing. It breaks the strict frame of the previous two alphabets, Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri. Mkhedruli letters begin to get coupled and more free calligraphy develops.[58]

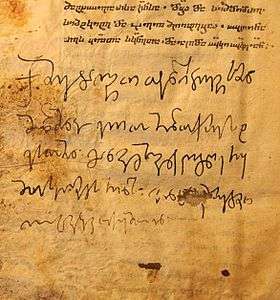

Example of one of the oldest Mkhedruli-written texts found in the royal charter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia, 11th century.

Modern Georgian alphabet

The modern Georgian alphabet consists of 33 letters:

| ა ani |

ბ bani |

გ gani |

დ doni |

ე eni |

ვ vini |

ზ zeni |

თ tani |

ი ini |

კ k'ani |

ლ lasi |

| მ mani |

ნ nari |

ო oni |

პ p'ari |

ჟ zhani |

რ rae |

ს sani |

ტ t'ari |

უ uni |

ფ pari |

ქ kani |

| ღ ghani |

ყ q'ari |

შ shini |

ჩ chini |

ც tsani |

ძ dzili |

წ ts'ili |

ჭ ch'ari |

ხ khani |

ჯ jani |

ჰ hae |

Letters removed from the Georgian alphabet

The Society for the Spreading of Literacy among Georgians, founded by Prince Ilia Chavchavadze in 1879, discarded five letters from the Georgian alphabet that had become redundant:[59]

| ჱ he |

ჲ hie |

ჳ vie |

ჴ qari |

ჵ hoe |

- ჱ (he), sometimes called "ei"[60] or "e-merve" ("eighth e"),[61] was equivalent to ეჲ ey, as in ქრისტჱ ~ ქრისტეჲ krist'ey 'Christ'.

- ჲ (hie), also called iota,[61] appeared instead of ი (ini) after a vowel, but came to have the same pronunciation as ი (ini) and was replaced by it. Thus ქრისტჱ ~ ქრისტეჲ krist'ey "Christ" is now written ქრისტეი krist'ei.

- ჳ (vie)[61] came to be pronounced the same as ვი vi and was replaced by that sequence, as in სხჳსი > სხვისი skhvisi "others'".

- ჴ (qari, hari)[61] came to be pronounced the same as ხ (khani), and was replaced by it. e.g. ჴლმწიფე became ხელმწიფე "sovereign".

- ჵ (hoe)[61] was used for the interjection hoi! and is now spelled ჰოი.

All but ჵ (hoe) continue to be used in the Svan alphabet; ჲ (hie) is used in the Mingrelian and Laz alphabets as well, for the y-sound /j/. Several others were used for Abkhaz and Ossetian in the short time they were written in Mkhedruli script.

Letters added to other alphabets

Mkhedruli has been adapted to languages besides Georgian. Some of these alphabets retained letters obsolete in Georgian, while others required additional letters:

| ჶ fi |

ჷ shva |

ჸ elifi |

ჹ turned gani |

ჺ aini |

- ჶ (fi "phi") is used in Laz and Svan, and formerly in Ossetian and Abkhazian.[2] It derives from the Greek letter Φ (phi).

- ჷ (shva "schwa"), also called yn, is used for the schwa sound in Svan and Mingrelian, and formerly in Ossetian and Abkhazian.[2]

- ჸ (elifi "alif") is used in for the glottal stop in Svan and Mingrelian.[2] It is a reversed ⟨ყ⟩ (q'ari).

- ჹ (turned gani) was once used for [ɢ] in evangelical literature in Dagestanian languages.[2]

- ჺ (aini "ain") is occasionally used for [ʕ] in Bats.[2] It derives from the Arabic letter ⟨ﻋ⟩ (‘ain).

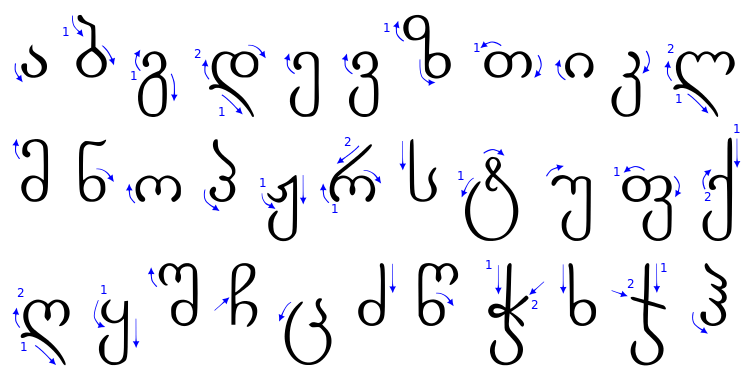

Handwriting of Mkhedruli

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Mkhedruli letter:[62][63][64]

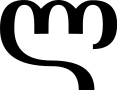

ზ, ო, and ხ (zeni, oni, khani) are almost always written without the small tick at the end, while the handwritten form of ჯ (jani) often uses a vertical line, ![]() (sometimes with a taller ascender, or with a diagonal cross bar); even when it is written at a diagonal, the cross-bar is generally shorter than in print.

(sometimes with a taller ascender, or with a diagonal cross bar); even when it is written at a diagonal, the cross-bar is generally shorter than in print.

- Only four letters are x-height, with neither ascenders nor descenders: ა, თ, ი, ო.

- Thirteen have ascenders, like b or d in English: ბ, ზ, მ, ნ, პ, რ, ს, შ, ჩ, ძ, წ, ხ, ჰ

- An equal number have descenders, like p or q in English: გ, დ, ე, ვ, კ, ლ, ჟ, ტ, უ, ფ, ღ, ყ, ც

- Three letters have both ascenders and descenders, like þ in Old English: ქ, ჭ, and (in handwriting) ჯ. წ has both ascender and descender in print, and sometimes in handwriting.

Variation

.jpg)

There is individual and stylistic variation in many of the letters. For example, the top circle of ზ (zeni) and the top stroke of რ (rae) may go in the other direction than shown in the chart (that is, counter-clockwise starting at 3 o'clock, and upwards – see the external-link section for videos of people writing). Other common variants:

გ (gani) may be written like ვ (vini) with a closed loop at the bottom.

დ (doni) is frequently written with a simple loop at top, ![]() .

.

კ, ც, and ძ (k'ani, tsani, dzili) are generally written with straight, vertical lines at the top, so that for example ც (tsani) resembles a U with a dimple in the right side.

ლ (lasi) is frequently written with a single arc, ![]() . Even when all three are written, they're generally not all the same size, as they are in print, but rather riding on one wide arc like two dimples in it.

. Even when all three are written, they're generally not all the same size, as they are in print, but rather riding on one wide arc like two dimples in it.

Rarely, ო (oni) is written as a right angle, ![]() .

.

რ (rae) is frequently written with one arc, ![]() , like a Latin ⟨h⟩.

, like a Latin ⟨h⟩.

ტ (t'ari) often has a small circle with a tail hanging into the bowl, rather than two small circles as in print, or as an O with a straight vertical line intersecting the top. It may also be rotated a bit clockwise, with the small circles further to the right and not as close to the top.

წ (ts'ili) is generally written with a round bowl at the bottom, ![]() . Another variation features a triangular bowl.

. Another variation features a triangular bowl.

ჭ (ch'ari) may be written without the hook at the top, and often with a completely straight vertical line.

ჱ (he) may be written without the loop, like a conflation of ს and ჰ.

ჯ ("jani") is sometimes written so that it looks like a hooked version of the Latin "X"

Similar letters

Several letters are similar and may be confused at first, especially in handwriting.

- For ვ (vini) and კ (k'ani), the critical difference is whether the top is a full arc or a (more-or-less) vertical line.

- For ვ (vini) and გ (gani), it is whether the bottom is an open curve or closed (a loop). The same is true of უ (uni) and შ (shini); in handwriting, the tops may look the same. Similarly ს (sani) and ხ (khani).

- For კ (k'ani) and პ (p'ari), the crucial difference is whether the letter is written below or above x-height, and whether it's written top-down or bottom-up.

- ძ (dzili) is written with a vertical top.

Ligatures, abbreviations and calligraphy

|

| Calligraphy |

|---|

Asomtavruli is often highly stylized and writers readily formed ligatures, intertwined letters, and placed letters within letters.[65]

A ligature of the Asomtavruli initials of King Vakhtang I of Iberia, Ⴂ Ⴌ (გნ, GN)

A ligature of the Asomtavruli letters Ⴃ Ⴀ (და, da) "and"

Nuskhuri, like Asomtavruli, is also often highly stylized. Writers readily formed ligatures and abbreviations for nomina sacra, including diacritics called karagma, which resemble titla. Because writing materials such as vellum were scarce and therefore precious, abbreviating was a practical measure widespread in manuscripts and hagiography by the 11th century.[66]

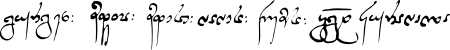

A Nuskhuri abbreviation of რომელი (romeli) "which"

A Nuskhuri abbreviation of იესუ ქრისტე (iesu kriste) "Jesus Christ"

Mkhedruli, in the 11th to 17th centuries also came to employ digraphs to the point that they were obligatory, requiring adhesion to a complex system.[67]

A Mkhedruli ligature of და (da) "and"

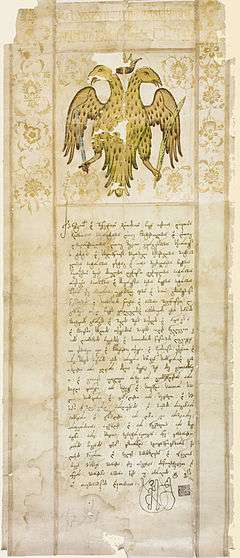

Mkhedruli calligraphy of Prince Garsevan Chavchavadze and King Archil of Imereti

Type faces

Georgian scripts come in only a single type face, though word processors can apply automatic ("fake")[68] oblique and bold formatting to Georgian text. Traditionally, Asomtavruli was used for chapter or section titles, where Latin script might use bold or italic type.

Punctuation

In Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri punctuation, various combinations of dots were used as word dividers and to separate phrases, clauses, and paragraphs. In monumental inscriptions and manuscripts of 5th to 10th centuries, these were written as dashes, like −, = and =−. In the 10th century, clusters of one (·), two (:), three (჻) and six (჻჻) dots (later sometimes small circles) were introduced by Ephrem Mtsire to indicate increasing breaks in the text. One dot indicated a "minor stop" (presumably a simple word break), two dots marked or separated "special words", three dots for a "bigger stop" (such as the appositive name and title "the sovereign Alexander", below, or the title of the Gospel of Matthew, above), and six dots were to indicate the end of the sentence. Starting in the 11th century, marks resembling the apostrophe and comma came into use. An apostrophe was used to mark an interrogative word, and a comma appeared at the end of an interrogative sentence. From the 12th century on, these were replaced with the semicolon (the Greek question mark). In the 18th century, Patriarch Anton I of Georgia reformed the system again, with commas, single dots, and double dots used to mark "complete", "incomplete", and "final" sentences, respectively.[69] For the most part, Georgian today uses the punctuation as in international usage of the Latin script.[70]

ჴლმწიფე ჻ ალექსანდრე

"The sovereign Alexander"

Summary

.jpg)

This table lists the three scripts in parallel columns, including the letters that are now obsolete in all alphabets (shown with a blue background), obsolete in Georgian but still used in other alphabets (green background), or additional letters in languages other than Georgian (pink background). The "national" transliteration is the system used by the Georgian government, whereas "Laz" is the Latin Laz alphabet used in Turkey. The table also shows the traditional numeric values of the letters.[71]

| Letters | Unicode (mkhedruli) |

Name | IPA | Transcriptions | Numeric value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| asomtavruli | nuskhuri | mkhedruli | National | ISO 9984 | BGN | Laz | ||||

| Ⴀ | ⴀ | ა | U+10D0 | ani | /ɑ/, Svan /a, æ/ | A a | A a | A a | A a | 1 |

| Ⴁ | ⴁ | ბ | U+10D1 | bani | /b/ | B b | B b | B b | B b | 2 |

| Ⴂ | ⴂ | გ | U+10D2 | gani | /ɡ/ | G g | G g | G g | G g | 3 |

| Ⴃ | ⴃ | დ | U+10D3 | doni | /d/ | D d | D d | D d | D d | 4 |

| Ⴄ | ⴄ | ე | U+10D4 | eni | /ɛ/ | E e | E e | E e | E e | 5 |

| Ⴅ | ⴅ | ვ | U+10D5 | vini | /v/ | V v | V v | V v | V v | 6 |

| Ⴆ | ⴆ | ზ | U+10D6 | zeni | /z/ | Z z | Z z | Z z | Z z | 7 |

| Ⴡ | ⴡ | ჱ | U+10F1 | he | /eɪ/, Svan /eː/ | — | Ē ē | Ey ey | — | 8 |

| Ⴇ | ⴇ | თ | U+10D7 | tani | /t⁽ʰ⁾/ | T t | T' t' | T' t' | T t | 9 |

| Ⴈ | ⴈ | ი | U+10D8 | ini | /i/ | I i | I i | I i | I i | 10 |

| Ⴉ | ⴉ | კ | U+10D9 | k'ani | /kʼ/ | K' k' | K k | K k | Ǩ ǩ | 20 |

| Ⴊ | ⴊ | ლ | U+10DA | lasi | /l/ | L l | L l | L l | L l | 30 |

| Ⴋ | ⴋ | მ | U+10DB | mani | /m/ | M m | M m | M m | M m | 40 |

| Ⴌ | ⴌ | ნ | U+10DC | nari | /n/ | N n | N n | N n | N n | 50 |

| Ⴢ | ⴢ | ჲ | U+10F2 | hie | /je/, Mingrelian, Laz, & Svan /j/ | — | Y y | J j | Y y | 60 |

| Ⴍ | ⴍ | ო | U+10DD | oni | /ɔ/, Svan /ɔ, œ/ | O o | O o | O o | O o | 70 |

| Ⴎ | ⴎ | პ | U+10DE | p'ari | /pʼ/ | P' p' | P p | P p | Ṗ ṗ | 80 |

| Ⴏ | ⴏ | ჟ | U+10DF | zhani | /ʒ/ | Zh zh | Ž ž | Zh zh | J j | 90 |

| Ⴐ | ⴐ | რ | U+10E0 | rae | /r/ | R r | R r | R r | R r | 100 |

| Ⴑ | ⴑ | ს | U+10E1 | sani | /s/ | S s | S s | S s | S s | 200 |

| Ⴒ | ⴒ | ტ | U+10E2 | t'ari | /tʼ/ | T' t' | T t | T t | Ť ť | 300 |

| Ⴣ | ⴣ | ჳ | U+10F3 | vie | /uɪ/, Svan /w/ | — | W w | — | — | 400[72] |

| Ⴓ | ⴓ | უ | U+10E3 | uni | /u/, Svan /u, y/ | U u | U u | U u | U u | 400[72] |

| Ⴧ | ⴧ | ჷ | U+10F7 | yn, schva | Mingrelian & Svan /ə/ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴔ | ⴔ | ფ | U+10E4 | pari | /p⁽ʰ⁾/ | P p | P' p' | P' p' | P p | 500 |

| Ⴕ | ⴕ | ქ | U+10E5 | kani | /k⁽ʰ⁾/ | K k | K' k' | K' k' | K k | 600 |

| Ⴖ | ⴖ | ღ | U+10E6 | ghani | /ʁ/ | Gh gh | Ḡ ḡ | Gh gh | Ğ ğ | 700 |

| Ⴗ | ⴗ | ყ | U+10E7 | q'ari | /qʼ/ | Q' q' | Q q | Q q | Q q | 800 |

| — | — | ჸ | U+10F8 | elif | Mingrelian & Svan /ʔ/ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴘ | ⴘ | შ | U+10E8 | shini | /ʃ/ | Sh sh | Š š | Sh sh | Ş ş | 900 |

| Ⴙ | ⴙ | ჩ | U+10E9 | chini | /tʃ⁽ʰ⁾/ | Ch ch | Č' č' | Ch' ch' | Ç ç | 1000 |

| Ⴚ | ⴚ | ც | U+10EA | tsani | /ts⁽ʰ⁾/ | Ts ts | C' c' | Ts' ts' | Ts ts | 2000 |

| Ⴛ | ⴛ | ძ | U+10EB | dzili | /dz/ | Dz dz | J j | Dz dz | Ž ž | 3000 |

| Ⴜ | ⴜ | წ | U+10EC | ts'ili | /tsʼ/ | Ts' ts' | C c | Ts ts | Ts’ ts’ | 4000 |

| Ⴝ | ⴝ | ჭ | U+10ED | ch'ari | /tʃʼ/ | Ch' ch' | Č č | Ch ch | Ç̌ ç̌ | 5000 |

| Ⴞ | ⴞ | ხ | U+10EE | khani | /χ/ | Kh kh | X x | Kh kh | X x | 6000 |

| Ⴤ | ⴤ | ჴ | U+10F4 | qari, hari | /q⁽ʰ⁾/ | — | H̠ ẖ | q' | — | 7000 |

| Ⴟ | ⴟ | ჯ | U+10EF | jani | /dʒ/ | J j | J̌ ǰ | J j | C c | 8000 |

| Ⴠ | ⴠ | ჰ | U+10F0 | hae | /h/ | H h | H h | H h | H h | 9000 |

| Ⴥ | ⴥ | ჵ | U+10F5 | hoe | /oː/ | — | Ō ō | — | — | 10000 |

| — | — | ჶ | U+10F6 | fi | Laz /f/ | — | F f | — | F f | — |

Use for other non-Kartvelian languages

- Ossetian language during the 1940s.[73]

- Abkhaz language during the 1940s.[74]

- Ingush language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[75]

- Chechen language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[76]

- Avar language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[77][78]

- Turkish language and Tatar language. A Turkish Gospel, dictionary, poems, medical book dating from the 18th century.[79]

- Persian language. The 18th-century Persian translation of the Arabic Gospel is kept at the National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi.

- Armenian language. In the Armenian community in Tbilisi, the Georgian script was occasionally used for writing Armenian in the 18th and 19th centuries, and some samples of this kind of texts are kept at the Georgian National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi.[80]

- Russian language. In the collections of the National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi there are also a few short poems in the Russian language written in Georgian script dating from the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

- Other Northeast Caucasian languages. The Georgian script was used for writing North Caucasian and Dagestani languages in connection with Georgian missionary activities in the areas starting in the 18th century.[81]

Old Avar crosses with Avar inscriptions in Asomtavruli script.

Computing

Unicode

The first Georgian script was included in Unicode Standard in October, 1991 with the release of version 1.0. In creating the Georgian Unicode block, important roles were played by German Jost Gippert, a linguist of Kartvelian studies, and American-Irish linguist and script-encoder Michael Everson, who created the Georgian Unicode for the Macintosh systems.[82] Significant contributions were also made by Anton Dumbadze and Irakli Garibashvili[83] (not to be mistaken with the former Prime Minister of Georgia Irakli Garibashvili).

Georgian Mkhedruli script received an official status for being Georgia's internationalized domain name script for (.გე).[84]

Blocks

The Unicode block for Georgian is U+10A0–U+10FF. Mkhedruli (modern Georgian) occupies the U+10D0–U+10FF range and Asomtavruli occupies the U+10A0–U+10CF range. The Unicode block for Georgian Supplement is U+2D00–U+2D2F and it encodes Nuskhuri.[2]

| Georgian[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+10Ax | Ⴀ | Ⴁ | Ⴂ | Ⴃ | Ⴄ | Ⴅ | Ⴆ | Ⴇ | Ⴈ | Ⴉ | Ⴊ | Ⴋ | Ⴌ | Ⴍ | Ⴎ | Ⴏ |

| U+10Bx | Ⴐ | Ⴑ | Ⴒ | Ⴓ | Ⴔ | Ⴕ | Ⴖ | Ⴗ | Ⴘ | Ⴙ | Ⴚ | Ⴛ | Ⴜ | Ⴝ | Ⴞ | Ⴟ |

| U+10Cx | Ⴠ | Ⴡ | Ⴢ | Ⴣ | Ⴤ | Ⴥ | Ⴧ | Ⴭ | ||||||||

| U+10Dx | ა | ბ | გ | დ | ე | ვ | ზ | თ | ი | კ | ლ | მ | ნ | ო | პ | ჟ |

| U+10Ex | რ | ს | ტ | უ | ფ | ქ | ღ | ყ | შ | ჩ | ც | ძ | წ | ჭ | ხ | ჯ |

| U+10Fx | ჰ | ჱ | ჲ | ჳ | ჴ | ჵ | ჶ | ჷ | ჸ | ჹ | ჺ | ჻ | ჼ | ჽ | ჾ | ჿ |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Georgian Supplement[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+2D0x | ⴀ | ⴁ | ⴂ | ⴃ | ⴄ | ⴅ | ⴆ | ⴇ | ⴈ | ⴉ | ⴊ | ⴋ | ⴌ | ⴍ | ⴎ | ⴏ |

| U+2D1x | ⴐ | ⴑ | ⴒ | ⴓ | ⴔ | ⴕ | ⴖ | ⴗ | ⴘ | ⴙ | ⴚ | ⴛ | ⴜ | ⴝ | ⴞ | ⴟ |

| U+2D2x | ⴠ | ⴡ | ⴢ | ⴣ | ⴤ | ⴥ | ⴧ | ⴭ | ||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Non-Unicode Applications

There is no non-Unicode character encoding for Georgian, which prevents non-Unicode applications from being able to support the Georgian script.

Keyboard layouts

Below is the standard Georgian-language keyboard layout, the traditional layout of manual typewriters.

| “ „ |

1 ! |

2 ? |

3 № |

4 § |

5 % |

6 : |

7 . |

8 ; |

9 , |

0 / |

- _ |

+ = |

← Backspace |

| Tab key | ღ | ჯ | უ | კ | ე ჱ | ნ | გ | შ | წ | ზ | ხ ჴ | ც | ) ( |

| Caps lock | ფ ჶ | ძ | ვ ჳ | თ | ა | პ | რ | ო | ლ | დ | ჟ | Enter key ↵ |

| Shift key ↑ |

ჭ | ჩ | ყ | ს | მ | ი ჲ | ტ | ქ | ბ | ჰ ჵ | Shift key ↑ |

| Control key | Win key | Alt key | Space bar | AltGr key | Win key | Menu key | Control key | |

Gallery

Gallery of Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri and Mkhedruli scripts.

Gallery of Asomtavruli

-

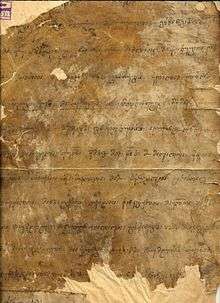

Asomtavruli of the 6th and 7th centuries

-

Asomtavruli at Barakoni

-

Asomtavruli Doliskana inscriptions

-

Asomtavruli at Ishkhani

-

Asomtavruli at Nikortsminda Cathedral

Gallery of Nuskhuri

-

Nuskhuri of 8th to 10th centuries

-

Nuskhuri of Jruchi Gospels, 13th century

-

Nuskhuri of the 11th century

-

.jpg)

Nuskhuri of Mokvi

-

Nuskhuri Iadgari of Mikael Modrekili, 10th century

-

Nuskhuri by Nikrai, 12th century

Gallery of Mkhedruli

-

Mkhedruli of King Bagrat IV of Georgia

-

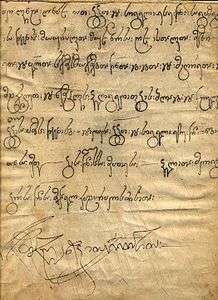

Mkhedruli of King George II of Georgia

-

Mkhedruli of King David IV of Georgia

-

Mkhedruli of King George III of Georgia

-

Mkhedruli of Queen Tamar of Georgia

-

Mkhedruli of King George IV of Georgia

-

Mkhedruli of King George V of Georgia

References

- ↑ Oldest found Georgian inscription so far. Exact date of introduction is unclear.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Unicode Standard, V. 6.3. U10A0, p. 3

- 1 2 Mzekala Shanidze (2000). "Greek influence in Georgian linguistics". In Sylvain Auroux; et al. History of the Language Sciences / Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaften / Histoire des sciences du langage. 1. Teilband. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 444–. ISBN 978-3-11-019400-5. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Seibt, Werner. "The Creation of the Caucasian Alphabets as Phenomenon of Cultural History".

- ↑ Machavariani, p. 329

- ↑ Standard Languages and Multilingualism in European History, Matthias Hüning, Ulrike Vogl, Olivier Moliner, John Benjamins Publishing, 2012, p.299

- ↑ "Georgian alphabet granted cultural heritage status". Agenda.ge. 10 March 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ↑ "Living culture of three writing systems of the Georgian alphabet". Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. UNESCO. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ↑ B. G. Hewitt (1995). Georgian: A Structural Reference Grammar. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-90-272-3802-3. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Hewitt, p. 4

- ↑ Barbara A. West; Oceania. Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia. p. 230. ISBN 9781438119137.

Archaeological work in the last decade has confirmed that a Georgian alphabet did exist very early in Georgia's history, with the first examples being dated from the fifth century C.E.

- ↑ Stephen H. Rapp. Studies in medieval Georgian historiography: early texts and Eurasian contexts. Peeters Publishers, 2003. ISBN 90-429-1318-5. p. 19, footnote 43: "The date of the supposed grave marker is hopelessly circumstantial ... I cannot support Chilashvili's dubious hypothesis."

- 1 2 Donald Rayfield The Literature of Georgia: A History (Caucasus World). RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1163-5. P. 19. "The Georgian alphabet seems unlikely to have a pre-Christian origin, for the major archaeological monument of the 1st century 4IX the bilingual Armazi gravestone commemorating Serafua, daughter of the Georgian viceroy of Mtskheta, is inscribed in Greek and Aramaic only. It has been believed, and not only in Armenia, that all the Caucasian alphabets — Armenian, Georgian and Caucaso-Albanian — were invented in the 4th century by the Armenian scholar Mesrop Mashtots.<...> The Georgian chronicles The Life of Kartli - assert that a Georgian script was invented two centuries before Christ, an assertion unsupported by archaeology. There is a possibility that the Georgians, like many minor nations of the area, wrote in a foreign language — Persian, Aramaic, or Greek — and translated back as they read."

- 1 2 Stephen H. Rapp Jr (2010). "Georgian Christianity". In Ken Parry. The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ S. H. Rapp, Recovering the Pre-National Caucasian Landscape, p38

- 1 2 Nino Kemertelidze (1999). "The Origin of Kartuli (Georgian) Writing (Alphabet)". In David Cram; Andrew R. Linn; Elke Nowak. History of Linguistics 1996: Volume 1: Traditions in Linguistics Worldwide. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 228–. ISBN 978-90-272-8382-5. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ Koryun's Life of Mashtots

- ↑ Glen Warren Bowersock, Peter Robert Lamont Brown, Oleg Grabar. Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-674-51173-5. P. 289. James R. Russell. Alphabets. "Mastoc' was a charismatic visionary who accomplished his task at a time when Armenia stood in danger of losing both its national identity, through partition, and its newly acquired Christian faith, through Sassanian pressure and reversion to paganism. By preaching in Armenian, he was able to undermine and co-opt the discourse founded in native tradition, and to create a counterweight against both Byzantine and Syriac cultural hegemony in the church. Mastoc' also created the Georgian and Caucasian-Albanian alphabets, based on the Armenian model."

- ↑ Georgian: ივ. ჯავახიშვილი, ქართული პალეოგრაფია, გვ. 205-208, 240-245

- ↑ Robert W. Thomson. Rewriting Caucasian history: the medieval Armenian adaptation of the Georgian Chronicles : the original Georgian texts and the Armenian adaptation. Clarendon Press, Oxford. p. xxii-xxiii. ISBN 0198263732.

- ↑ Stephen H. Rapp. Studies in medieval Georgian historiography: early texts and Eurasian contexts. Peeters Publishers, 2003. ISBN 90-429-1318-5. P. 450. "There is also the claim advanced by Koriwn in his saintly biography of Mashtoc' (Mesrop) that the Georgian script had been invented at the direction of Mashtoc'. Yet it is within the realm of possibility that this tradition, repeated by many later Armenian historians, may not have been part of the original fifth-century text at all but added after 607. Significantly, all of the extant MSS containing The Life of Mashtoc* were copied centuries after the split. Consequently, scribal manipulation reflecting post-schism (especially anti-Georgian) attitudes potentially contaminates all MSS copied after that time. It is therefore conceivable, though not yet proven, that valuable information about Georgia transmitted by pre-schism Armenian texts was excised by later, post-schism individuals."

- ↑ Greppin, John A.C.: Some comments on the origin of the Georgian alphabet. — Bazmavep 139, 1981, 449-456

- ↑ Harald Haarmann (2012). "Ethnic Conflict and standardisation in the Caucasus". In Matthias Hüning; Ulrike Vogl; Olivier Moliner. Standard Languages and Multilingualism in European History. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-90-272-0055-6. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Peter T. Daniels, The World's Writing Systems, p. 367

- ↑ Machavariani, p. 177

- ↑ ქსე, ტ. 7, თბ., 1984, გვ. 651-652

- ↑ შანიძე ა., ქართული საბჭოთა ენციკლოპედია, ტ. 2, გვ. 454-455, თბ., 1977 წელი

- ↑ კ. დანელია, ზ. სარჯველაძე, ქართული პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1997, გვ. 218-219

- ↑ ე. მაჭავარიანი, მწიგნობრობაჲ ქართული, თბილისი, 1989

- ↑ პ. ინგოროყვა, „შოთა რუსთაველი“, „მნათობი“, 1966, № 3, გვ. 116

- ↑ Machavariani, pp. 121-122

- ↑ რ. პატარიძე, ქართული ასომთავრული, თბილისი, 1980, გვ. 151, 260-261

- ↑ ივ. ჯავახიშვილი, ქართული დამწერლობათა-მცოდნეობა ანუ პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1949, 185-187

- ↑ ე. მაჭავარიანი, ქართული ანბანი, თბილისი, 1977, გვ. 5-6

- ↑ ელენე მაჭავარიანი, ენციკლოპედია „ქართული ენა“, თბილისი, 2008, გვ. 403-404

- ↑ ვ. სილოგავა, ენციკლოპედია „ქართული ენა“, თბილისი, 2008, გვ. 269-271

- ↑ ივ. ჯავახიშვილი, ქართული დამწერლობათა-მცოდნეობა ანუ პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1949, 124-126

- ↑ Machavariani, p. 120

- ↑ Machavariani, p. 129

- ↑ ივ. ჯავახიშვილი, ქართული დამწერლობათა-მცოდნეობა ანუ პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1949, 127-128

- ↑ Mchedlidze, p. 105

- 1 2 კ. დანელია, ზ. სარჯველაძე, ქართული პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1997, გვ. 219

- ↑ B. George Hewitt, 1995, Georgian: A Structural Reference Grammar, p. 4

- ↑ გ. აბრამიშვილი, ატენის სიონის უცნობი წარწერები, "მაცნე" (ისტ. და არქეოლოგ. სერია), 1976, №2, გვ. 170

- ↑ კ. დანელია, ზ. სარჯველაძე, ქართული პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1997, გვ. 218

- ↑ ე. მაჭავარიანი, ქართული ანბანი, თბილისი, 1977

- ↑ Mchedlidze, p. 107

- ↑ About Georgian calligraphy Lasha Kintsurashvili

- ↑ Gillam, Richard Unicode Demystified: A Practical Programmer's Guide to the Encoding Standard p.252

- ↑ Julie D. Allen Unicode standard, version 5.0 p.249

- ↑ (Georgian) ილია მეორე ერს ქართული ენის დაცვისკენ კიდევ ერთხელ მოუწოდებს საქინფორმ.გე

- ↑ Writing Systems of the World, Akira Nakanishi, p. 22

- ↑ Georgica: A Journal of Georgian and Caucasian Studies, Issues 4-5, William Edward David Allen, A. Gugushvili, S. Austin and Sons, Limited, 1937, p. 324

- ↑ ატენის სიონის უცნობი წარწერები, აბრამიშვილი, გვ. 170-1

- ↑ The Languages of the World, Kenneth Katzner, p. 118

- ↑ Chambers's encyclopaedia: a dictionary of universal knowledge, Volume 5, Chambers, David Patrick, William Geddie, W. & R. Chambers, Limited, 1901, page 165

- ↑ T. Putkaradze, History of Georgian language, Development of the Georgian writing system, paragraph II, 2.1.5. 2006

- ↑ მაჭავარიანი, თბილისი, 1977

- ↑ The World's Writing Systems, Peter T. Daniels, The Georgian Alphabet, p. 367

- ↑ Akaki Shanidze, The Basics of the Georgian language grammar, Tbilisi, 1973/1980, p. 18

- 1 2 3 4 5 Otar Jishkariani, Praise of the Alphabet, 1986, Tbilisi, p. 1

- ↑ Aronson, pp. 21-25

- ↑ Stefano Paolini, Nikoloz Cholokashvili, Dittionario giorgiano e italiano, Palazzo di Propaganda Fide, Rome, 1629

- ↑ Mchedlidze, p. 110

- ↑ Ingorokva, Pavle ქართული დამწერლობის ძეგლები ანტიკური ხანისა (The monuments of ancient Georgian script)

- ↑ Shanidze, Akaki (2003), ქართული ენა [The Georgian Language] (in Georgian), Tbilisi, ISBN 1-4020-1440-6

- ↑ შანიძე, 2003

- ↑ Fake vs True Italics

- ↑ Georgian Soviet Encyclopedia, V. 8, p. 231, Tbilisi, 1984

- ↑ Unicode Demystified: A Practical Programmer's Guide to the Encoding Standard, Richard Gillam, p. 252

- ↑ Aronson (1990), pp. 30–31.

- 1 2 ჳ and უ have the same numeric value (400)

- ↑ The Politics of Ethnic Separatism in Russia and Georgia, Julie A. George, p. 104

- ↑ The Abkhazians: A Handbook, George Hewitt, p. 171

- ↑ Язык, история и культура вайнахов, И. Ю Алироев p.85, Чех-Инг. изд.-полигр. об-ние "Книга", 1990

- ↑ Чеченский язык, И. Ю. Алироев, p.24, Академия, 1999

- ↑ Грузинско-дагестанские языковые контакты, Маджид Шарипович Халилов p.29, Наука, 2004

- ↑ История аварцев, М. Г Магомедов p.150, Дагестанский гос. университет, 2005

- ↑ Enwall, Joakim (2010), "Turkish texts in Georgian script: Sociolinguistic and ethno-linguistic aspects", in Boeschoten, Hendrik; Rentzsch, Julian (eds.), Turcology in Mainz, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-06113-8, pp. 144–145

- ↑ Hendrik Boeschoten, Julian Rentzsch (2010) Turcology in Mainz, p. 137

- ↑ Enwall, Joakim (2010), "Turkish texts in Georgian script: Sociolinguistic and ethno-linguistic aspects", in Boeschoten, Hendrik; Rentzsch, Julian (eds.), Turcology in Mainz, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-06113-8, pp. 137–138

- ↑ უნიკოდში ქართულის ასახვის ისტორია (History of the Georgian Unicode) Georgian Unicode fonts by BPG-InfoTech

- ↑ Font Contributors Acknowledgements Unicode

- ↑ (Georgian) საქართველოში საინტერნეტო მისამართები მხედრული ანბანით დაიწერება Rustavi 2

Bibliography

- Aronson, Howard I. (1990), Georgian: a reading grammar (second ed.), Columbus, OH: Slavica

- Shosted, Ryan K.; Chikovani, Vakhtang (2006), "Standard Georgian", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 36 (2): 255–264, doi:10.1017/S0025100306002659

- Javakhishvili, I. Georgian palaeography Tbilisi, 1949

- Barnaveli, T. Inscriptions of Ateni Sioni Tbilisi, 1977

- Pataridze, R. Georgian Asomtavruli Tbilisi, 1980

- Machavariani, E. Georgian manuscripts Tbilisi, 2011

- Gamkrelidze, T. Writing system and the old Georgian script Tbilisi, 1989

- Kilanawa, B. Georgian script in the writing systems Tbilisi, 1990

- Hewitt, B.G. (1995). Georgian: A Structural Reference Grammar. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-3802-3.

- Mchedlidze, T. The restored Georgian alphabet, Fulda, Germany, 2013

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Georgian scripts. |

- Gallery of Mkhedruli, Omniglot page on Mkhedruli which shows some stylistic variations mentioned above

- Georgian alphabet animation on YouTube, produced by the Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia. Gives the sound of each letter, illustrates several fonts, and shows the stroke order of each letter.

- Lasha Kintsurashvili and Levan Chaganava, submissions to the 2014 International Exhibition of Calligraphy

- Reference grammar of Georgian by Howard Aronson (SEELRC, Duke University)

- Georgian transliteration + Georgian virtual keyboard

- "Unicode Code Chart (10A0–10FF) for Georgian scripts" (PDF). (105 KB)

- "Transliteration of Georgian" (PDF). (105 KB)