Biology

| ||||

Biology deals with the study of the many living organisms.

|

Biology is a natural science concerned with the study of life and living organisms, including their structure, function, growth, evolution, distribution, identification and taxonomy.[1] Modern biology is a vast and eclectic field, composed of many branches and subdisciplines. However, despite the broad scope of biology, there are certain general and unifying concepts within it that govern all study and research, consolidating it into single, coherent field. In general, biology recognizes the cell as the basic unit of life, genes as the basic unit of heredity, and evolution as the engine that propels the synthesis and creation of new species. It is also understood today that all the organisms survive by consuming and transforming energy and by regulating their internal environment to maintain a stable and vital condition known as homeostasis.

Sub-disciplines of biology are defined by the scale at which organisms are studied, the kinds of organisms studied, and the methods used to study them: biochemistry examines the rudimentary chemistry of life; molecular biology studies the complex interactions among biological molecules; botany studies the biology of plants; cellular biology examines the basic building-block of all life, the cell; physiology examines the physical and chemical functions of tissues, organs, and organ systems of an organism; evolutionary biology examines the processes that produced the diversity of life; and ecology examines how organisms interact in their environment.[2]

History

The term biology is derived from the Greek word βίος, bios, "life" and the suffix -λογία, -logia, "study of."[3][4] The Latin-language form of the term first appeared in 1736 when Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus (Carl von Linné) used biologi in his Bibliotheca botanica. It was used again in 1766 in a work entitled Philosophiae naturalis sive physicae: tomus III, continens geologian, biologian, phytologian generalis, by Michael Christoph Hanov, a disciple of Christian Wolff. The first German use, Biologie, was in a 1771 translation of Linnaeus' work. In 1797, Theodor Georg August Roose used the term in the preface of a book, Grundzüge der Lehre van der Lebenskraft. Karl Friedrich Burdach used the term in 1800 in a more restricted sense of the study of human beings from a morphological, physiological and psychological perspective (Propädeutik zum Studien der gesammten Heilkunst). The term came into its modern usage with the six-volume treatise Biologie, oder Philosophie der lebenden Natur (1802–22) by Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus, who announced:[5]

- The objects of our research will be the different forms and manifestations of life, the conditions and laws under which these phenomena occur, and the causes through which they have been effected. The science that concerns itself with these objects we will indicate by the name biology [Biologie] or the doctrine of life [Lebenslehre].

Although modern biology is a relatively recent development, sciences related to and included within it have been studied since ancient times. Natural philosophy was studied as early as the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indian subcontinent, and China. However, the origins of modern biology and its approach to the study of nature are most often traced back to ancient Greece.[6][7] While the formal study of medicine dates back to Hippocrates (ca. 460 BC – ca. 370 BC), it was Aristotle (384 BC – 322 BC) who contributed most extensively to the development of biology. Especially important are his History of Animals and other works where he showed naturalist leanings, and later more empirical works that focused on biological causation and the diversity of life. Aristotle's successor at the Lyceum, Theophrastus, wrote a series of books on botany that survived as the most important contribution of antiquity to the plant sciences, even into the Middle Ages.[8]

Scholars of the medieval Islamic world who wrote on biology included al-Jahiz (781–869), Al-Dīnawarī (828–896), who wrote on botany,[9] and Rhazes (865–925) who wrote on anatomy and physiology. Medicine was especially well studied by Islamic scholars working in Greek philosopher traditions, while natural history drew heavily on Aristotelian thought, especially in upholding a fixed hierarchy of life.

Biology began to quickly develop and grow with Anton van Leeuwenhoek's dramatic improvement of the microscope. It was then that scholars discovered spermatozoa, bacteria, infusoria and the diversity of microscopic life. Investigations by Jan Swammerdam led to new interest in entomology and helped to develop the basic techniques of microscopic dissection and staining.[10]

Advances in microscopy also had a profound impact on biological thinking. In the early 19th century, a number of biologists pointed to the central importance of the cell. Then, in 1838, Schleiden and Schwann began promoting the now universal ideas that (1) the basic unit of organisms is the cell and (2) that individual cells have all the characteristics of life, although they opposed the idea that (3) all cells come from the division of other cells. Thanks to the work of Robert Remak and Rudolf Virchow, however, by the 1860s most biologists accepted all three tenets of what came to be known as cell theory.[11][12]

Meanwhile, taxonomy and classification became the focus of natural historians. Carl Linnaeus published a basic taxonomy for the natural world in 1735 (variations of which have been in use ever since), and in the 1750s introduced scientific names for all his species.[13] Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, treated species as artificial categories and living forms as malleable—even suggesting the possibility of common descent. Though he was opposed to evolution, Buffon is a key figure in the history of evolutionary thought; his work influenced the evolutionary theories of both Lamarck and Darwin.[14]

Serious evolutionary thinking originated with the works of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who was the first to present a coherent theory of evolution.[15] He posited that evolution was the result of environmental stress on properties of animals, meaning that the more frequently and rigorously an organ was used, the more complex and efficient it would become, thus adapting the animal to its environment. Lamarck believed that these acquired traits could then be passed on to the animal's offspring, who would further develop and perfect them.[16] However, it was the British naturalist Charles Darwin, combining the biogeographical approach of Humboldt, the uniformitarian geology of Lyell, Malthus's writings on population growth, and his own morphological expertise and extensive natural observations, who forged a more successful evolutionary theory based on natural selection; similar reasoning and evidence led Alfred Russel Wallace to independently reach the same conclusions.[17][18] Although it was the subject of controversy (which continues to this day), Darwin's theory quickly spread through the scientific community and soon became a central axiom of the rapidly developing science of biology.

The discovery of the physical representation of heredity came along with evolutionary principles and population genetics. In the 1940s and early 1950s, experiments pointed to DNA as the component of chromosomes that held the trait-carrying units that had become known as genes. A focus on new kinds of model organisms such as viruses and bacteria, along with the discovery of the double helical structure of DNA in 1953, marked the transition to the era of molecular genetics. From the 1950s to present times, biology has been vastly extended in the molecular domain. The genetic code was cracked by Har Gobind Khorana, Robert W. Holley and Marshall Warren Nirenberg after DNA was understood to contain codons. Finally, the Human Genome Project was launched in 1990 with the goal of mapping the general human genome. This project was essentially completed in 2003,[19] with further analysis still being published. The Human Genome Project was the first step in a globalized effort to incorporate accumulated knowledge of biology into a functional, molecular definition of the human body and the bodies of other organisms.

Foundations of modern biology

Cell theory

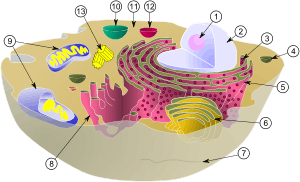

Cell theory states that the cell is the fundamental unit of life, and that all living things are composed of one or more cells or the secreted products of those cells (e.g. shells, hairs and nails etc.). All cells arise from other cells through cell division. In multicellular organisms, every cell in the organism's body derives ultimately from a single cell in a fertilized egg. The cell is also considered to be the basic unit in many pathological processes.[20] In addition, the phenomenon of energy flow occurs in cells in processes that are part of the function known as metabolism. Finally, cells contain hereditary information (DNA), which is passed from cell to cell during cell division.

Evolution

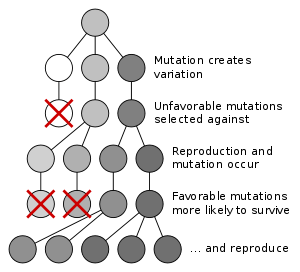

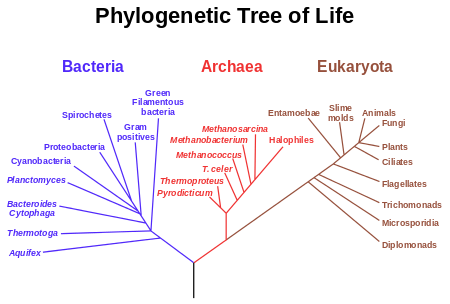

A central organizing concept in biology is that life changes and develops through evolution, and that all life-forms known have a common origin. The theory of evolution postulates that all organisms on the Earth, both living and extinct, have descended from a common ancestor or an ancestral gene pool. This last universal common ancestor of all organisms is believed to have appeared about 3.5 billion years ago.[21] Biologists generally regard the universality and ubiquity of the genetic code as definitive evidence in favor of the theory of universal common descent for all bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes (see: origin of life).[22]

Introduced into the scientific lexicon by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck in 1809,[23] evolution was established by Charles Darwin fifty years later as a viable scientific model when he articulated its driving force: natural selection.[24][25][26] (Alfred Russel Wallace is recognized as the co-discoverer of this concept as he helped research and experiment with the concept of evolution.)[27] Evolution is now used to explain the great variations of life found on Earth.

Darwin theorized that species and breeds developed through the processes of natural selection and artificial selection or selective breeding.[28] Genetic drift was embraced as an additional mechanism of evolutionary development in the modern synthesis of the theory.[29]

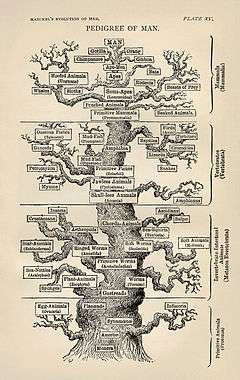

The evolutionary history of the species—which describes the characteristics of the various species from which it descended—together with its genealogical relationship to every other species is known as its phylogeny. Widely varied approaches to biology generate information about phylogeny. These include the comparisons of DNA sequences conducted within molecular biology or genomics, and comparisons of fossils or other records of ancient organisms in paleontology.[30] Biologists organize and analyze evolutionary relationships through various methods, including phylogenetics, phenetics, and cladistics. (For a summary of major events in the evolution of life as currently understood by biologists, see evolutionary timeline.)

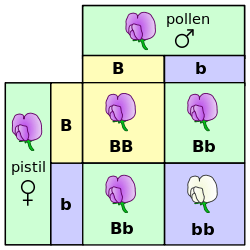

Genetics

Genes are the primary units of inheritance in all organisms. A gene is a unit of heredity and corresponds to a region of DNA that influences the form or function of an organism in specific ways. All organisms, from bacteria to animals, share the same basic machinery that copies and translates DNA into proteins. Cells transcribe a DNA gene into an RNA version of the gene, and a ribosome then translates the RNA into a protein, a sequence of amino acids. The translation code from RNA codon to amino acid is the same for most organisms, but slightly different for some. For example, a sequence of DNA that codes for insulin in humans also codes for insulin when inserted into other organisms, such as plants.[31]

DNA usually occurs as linear chromosomes in eukaryotes, and circular chromosomes in prokaryotes. A chromosome is an organized structure consisting of DNA and histones. The set of chromosomes in a cell and any other hereditary information found in the mitochondria, chloroplasts, or other locations is collectively known as its genome. In eukaryotes, genomic DNA is located in the cell nucleus, along with small amounts in mitochondria and chloroplasts. In prokaryotes, the DNA is held within an irregularly shaped body in the cytoplasm called the nucleoid.[32] The genetic information in a genome is held within genes, and the complete assemblage of this information in an organism is called its genotype.[33]

Homeostasis

Homeostasis is the ability of an open system to regulate its internal environment to maintain stable conditions by means of multiple dynamic equilibrium adjustments controlled by interrelated regulation mechanisms. All living organisms, whether unicellular or multicellular, exhibit homeostasis.[35]

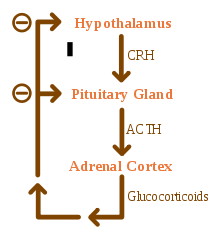

To maintain dynamic equilibrium and effectively carry out certain functions, a system must detect and respond to perturbations. After the detection of a perturbation, a biological system normally responds through negative feedback. This means stabilizing conditions by either reducing or increasing the activity of an organ or system. One example is the release of glucagon when sugar levels are too low.

Energy

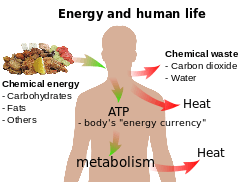

The survival of a living organism depends on the continuous input of energy. Chemical reactions that are responsible for its structure and function are tuned to extract energy from substances that act as its food and transform them to help form new cells and sustain them. In this process, molecules of chemical substances that constitute food play two roles; first, they contain energy that can be transformed for biological chemical reactions; second, they develop new molecular structures made up of biomolecules.

The organisms responsible for the introduction of energy into an ecosystem are known as producers or autotrophs. Nearly all of these organisms originally draw energy from the sun.[36] Plants and other phototrophs use solar energy via a process known as photosynthesis to convert raw materials into organic molecules, such as ATP, whose bonds can be broken to release energy.[37] A few ecosystems, however, depend entirely on energy extracted by chemotrophs from methane, sulfides, or other non-luminal energy sources.[38]

Some of the captured energy is used to produce biomass to sustain life and provide energy for growth and development. The majority of the rest of this energy is lost as heat and waste molecules. The most important processes for converting the energy trapped in chemical substances into energy useful to sustain life are metabolism[39] and cellular respiration.[40]

Study and research

Structural

Molecular biology is the study of biology at a molecular level.[41] This field overlaps with other areas of biology, particularly with genetics and biochemistry. Molecular biology chiefly concerns itself with understanding the interactions between the various systems of a cell, including the interrelationship of DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis and learning how these interactions are regulated.

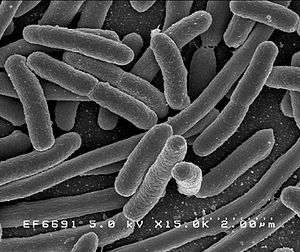

Cell biology studies the structural and physiological properties of cells, including their behaviors, interactions, and environment. This is done on both the microscopic and molecular levels, for unicellular organisms such as bacteria, as well as the specialized cells in multicellular organisms such as humans. Understanding the structure and function of cells is fundamental to all of the biological sciences. The similarities and differences between cell types are particularly relevant to molecular biology.

Anatomy considers the forms of macroscopic structures such as organs and organ systems.[42]

Genetics is the science of genes, heredity, and the variation of organisms.[43][44] Genes encode the information necessary for synthesizing proteins, which in turn play a central role in influencing the final phenotype of the organism. In modern research, genetics provides important tools in the investigation of the function of a particular gene, or the analysis of genetic interactions. Within organisms, genetic information generally is carried in chromosomes, where it is represented in the chemical structure of particular DNA molecules.

Developmental biology studies the process by which organisms grow and develop. Originating in embryology, modern developmental biology studies the genetic control of cell growth, differentiation, and "morphogenesis," which is the process that progressively gives rise to tissues, organs, and anatomy. Model organisms for developmental biology include the round worm Caenorhabditis elegans,[45] the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster,[46] the zebrafish Danio rerio,[47] the mouse Mus musculus,[48] and the weed Arabidopsis thaliana.[49][50] (A model organism is a species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in that organism provide insight into the workings of other organisms.)[51]

Physiological

Physiology studies the mechanical, physical, and biochemical processes of living organisms by attempting to understand how all of the structures function as a whole. The theme of "structure to function" is central to biology. Physiological studies have traditionally been divided into plant physiology and animal physiology, but some principles of physiology are universal, no matter what particular organism is being studied. For example, what is learned about the physiology of yeast cells can also apply to human cells. The field of animal physiology extends the tools and methods of human physiology to non-human species. Plant physiology borrows techniques from both research fields.

Physiology studies how for example nervous, immune, endocrine, respiratory, and circulatory systems, function and interact. The study of these systems is shared with medically oriented disciplines such as neurology and immunology.

Evolutionary

Evolutionary research is concerned with the origin and descent of species, as well as their change over time, and includes scientists from many taxonomically oriented disciplines. For example, it generally involves scientists who have special training in particular organisms such as mammalogy, ornithology, botany, or herpetology, but use those organisms as systems to answer general questions about evolution.

Evolutionary biology is partly based on paleontology, which uses the fossil record to answer questions about the mode and tempo of evolution,[52] and partly on the developments in areas such as population genetics.[53] In the 1980s, developmental biology re-entered evolutionary biology from its initial exclusion from the modern synthesis through the study of evolutionary developmental biology.[54] Related fields often considered part of evolutionary biology are phylogenetics, systematics, and taxonomy.

Systematic

Multiple speciation events create a tree structured system of relationships between species. The role of systematics is to study these relationships and thus the differences and similarities between species and groups of species.[55] However, systematics was an active field of research long before evolutionary thinking was common.[56]

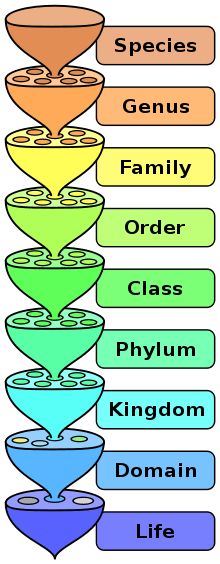

Traditionally, living things have been divided into five kingdoms: Monera; Protista; Fungi; Plantae; Animalia.[57] However, many scientists now consider this five-kingdom system outdated. Modern alternative classification systems generally begin with the three-domain system: Archaea (originally Archaebacteria); Bacteria (originally Eubacteria) and Eukaryota (including protists, fungi, plants, and animals)[58] These domains reflect whether the cells have nuclei or not, as well as differences in the chemical composition of key biomolecules such as ribosomes.[58]

Further, each kingdom is broken down recursively until each species is separately classified. The order is: Domain; Kingdom; Phylum; Class; Order; Family; Genus; Species.

Outside of these categories, there are obligate intracellular parasites that are "on the edge of life"[59] in terms of metabolic activity, meaning that many scientists do not actually classify these structures as alive, due to their lack of at least one or more of the fundamental functions or characteristics that define life. They are classified as viruses, viroids, prions, or satellites.

The scientific name of an organism is generated from its genus and species. For example, humans are listed as Homo sapiens. Homo is the genus, and sapiens the species. When writing the scientific name of an organism, it is proper to capitalize the first letter in the genus and put all of the species in lowercase.[60] Additionally, the entire term may be italicized or underlined.[61]

The dominant classification system is called the Linnaean taxonomy. It includes ranks and binomial nomenclature. How organisms are named is governed by international agreements such as the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN), the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), and the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (ICNB). The classification of viruses, viroids, prions, and all other sub-viral agents that demonstrate biological characteristics is conducted by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) and is known as the International Code of Viral Classification and Nomenclature (ICVCN).[62][63][64][65] However, several other viral classification systems do exist.

A merging draft, BioCode, was published in 1997 in an attempt to standardize nomenclature in these three areas, but has yet to be formally adopted.[66] The BioCode draft has received little attention since 1997; its originally planned implementation date of January 1, 2000, has passed unnoticed. A revised BioCode that, instead of replacing the existing codes, would provide a unified context for them, was proposed in 2011.[67][68][69] However, the International Botanical Congress of 2011 declined to consider the BioCode proposal. The ICVCN remains outside the BioCode, which does not include viral classification.

Kingdoms

-

Animalia – Bos primigenius taurus

-

Planta – Triticum

-

Fungi – Morchella esculenta

-

Stramenopila/Chromista – Fucus serratus

-

Bacteria – Gemmatimonas aurantiaca (- = 1 Micrometer)

-

Archaea – Halobacteria

-

Virus – Gamma phage

Ecological and environmental

Ecology studies the distribution and abundance of living organisms, and the interactions between organisms and their environment.[70] The habitat of an organism can be described as the local abiotic factors such as climate and ecology, in addition to the other organisms and biotic factors that share its environment.[71] One reason that biological systems can be difficult to study is that so many different interactions with other organisms and the environment are possible, even on small scales. A microscopic bacterium in a local sugar gradient is responding to its environment as much as a lion searching for food in the African savanna. For any species, behaviors can be co-operative, competitive, parasitic, or symbiotic. Matters become more complex when two or more species interact in an ecosystem.

Ecological systems are studied at several different levels, from individuals and populations to ecosystems and the biosphere. The term population biology is often used interchangeably with population ecology, although population biology is more frequently used when studying diseases, viruses, and microbes, while population ecology is more commonly used when studying plants and animals. Ecology draws on many subdisciplines.

Ethology studies animal behavior (particularly that of social animals such as primates and canids), and is sometimes considered a branch of zoology. Ethologists have been particularly concerned with the evolution of behavior and the understanding of behavior in terms of the theory of natural selection. In one sense, the first modern ethologist was Charles Darwin, whose book, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, influenced many ethologists to come.[72]

Biogeography studies the spatial distribution of organisms on the Earth, focusing on topics like plate tectonics, climate change, dispersal and migration, and cladistics.

Basic unresolved problems in biology

Despite the profound advances made over recent decades in our understanding of life's fundamental processes, some basic problems have remained unresolved. For example, one of the major unresolved problems in biology is the primary adaptive function of sex, and particularly its key processes in eukaryotes, meiosis and homologous recombination. One view is that sex evolved primarily as an adaptation for increasing genetic diversity (see references e.g.[73][74]). An alternative view is that sex is an adaptation for promoting accurate DNA repair in germ-line DNA, and that increased genetic diversity is primarily a byproduct that may be useful in the long run.[75][76] (See also Evolution of sexual reproduction).

Another basic unresolved problem in biology is the biologic basis of aging. At present, there is no consensus view on the underlying cause of aging. Various competing theories are outlined in Ageing Theories.

Branches

These are the main branches of biology:[77][78]

- Aerobiology – the study of airborne organic particles

- Agriculture – the study of producing crops and raising livestock, with an emphasis on practical applications

- Anatomy – the study of form and function, in plants, animals, and other organisms, or specifically in humans

- Histology – the study of cells and tissues, a microscopic branch of anatomy

- Astrobiology (also known as exobiology, exopaleontology, and bioastronomy) – the study of evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe

- Biochemistry – the study of the chemical reactions required for life to exist and function, usually a focus on the cellular level

- Bioengineering – the study of biology through the means of engineering with an emphasis on applied knowledge and especially related to biotechnology

- Biogeography – the study of the distribution of species spatially and temporally

- Bioinformatics – the use of information technology for the study, collection, and storage of genomic and other biological data

- Biomathematics (or Mathematical biology) – the quantitative or mathematical study of biological processes, with an emphasis on modeling

- Biomechanics – often considered a branch of medicine, the study of the mechanics of living beings, with an emphasis on applied use through prosthetics or orthotics

- Biomedical research – the study of health and disease

- Pharmacology – the study and practical application of preparation, use, and effects of drugs and synthetic medicines

- Biomusicology – the study of music from a biological point of view.

- Biophysics – the study of biological processes through physics, by applying the theories and methods traditionally used in the physical sciences

- Biosemiotics – the study of biological processes through semiotics, by applying the models of meaning-making and communication

- Biotechnology – the study of the manipulation of living matter, including genetic modification and synthetic biology

- Synthetic biology – research integrating biology and engineering; construction of biological functions not found in nature

- Building biology – the study of the indoor living environment

- Botany – the study of plants

- Cell biology – the study of the cell as a complete unit, and the molecular and chemical interactions that occur within a living cell

- Cognitive biology – the study of cognition as a biological function

- Conservation biology – the study of the preservation, protection, or restoration of the natural environment, natural ecosystems, vegetation, and wildlife

- Cryobiology – the study of the effects of lower than normally preferred temperatures on living beings

- Developmental biology – the study of the processes through which an organism forms, from zygote to full structure

- Embryology – the study of the development of embryo (from fecundation to birth)

- Ecology – the study of the interactions of living organisms with one another and with the non-living elements of their environment

- Environmental biology – the study of the natural world, as a whole or in a particular area, especially as affected by human activity

- Epidemiology – a major component of public health research, studying factors affecting the health of populations

- Evolutionary biology – the study of the origin and descent of species over time

- Genetics – the study of genes and heredity.

- Epigenetics – the study of heritable changes in gene expression or cellular phenotype caused by mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence

- Hematology (also known as Haematology) – the study of blood and blood-forming organs.

- Integrative biology – the study of whole organisms

- Limnology – the study of inland waters

- Marine biology (or Biological oceanography) – the study of ocean ecosystems, plants, animals, and other living beings

- Microbiology – the study of microscopic organisms (microorganisms) and their interactions with other living things

- Bacteriology – the study of bacteria

- Mycology – the study of fungi

- Parasitology – the study of parasites and parasitism

- Virology – the study of viruses and some other virus-like agents

- Molecular biology – the study of biology and biological functions at the molecular level, some cross over with biochemistry

- Nanobiology – the study of how nanotechnology can be used in biology, and the study of living organisms and parts on the nanoscale level of organization

- Neurobiology – the study of the nervous system, including anatomy, physiology and pathology

- Population biology – the study of groups of conspecific organisms, including

- Population ecology – the study of how population dynamics and extinction

- Population genetics – the study of changes in gene frequencies in populations of organisms

- Paleontology – the study of fossils and sometimes geographic evidence of prehistoric life

- Pathobiology or pathology – the study of diseases, and the causes, processes, nature, and development of disease

- Physiology – the study of the functioning of living organisms and the organs and parts of living organisms

- Phytopathology – the study of plant diseases (also called Plant Pathology)

- Psychobiology – the study of the biological bases of psychology

- Quantum biology – the study of quantum mechanics to biological objects and problems.

- Sociobiology – the study of the biological bases of sociology

- Structural biology – a branch of molecular biology, biochemistry, and biophysics concerned with the molecular structure of biological macromolecules

- Zoology – the study of animals, including classification, physiology, development, and behavior, including:

- Ethology – the study of animal behavior

- Entomology – the study of insects

- Herpetology – the study of reptiles and amphibians

- Ichthyology – the study of fish

- Mammalogy – the study of mammals

- Ornithology – the study of birds

See also

- Glossary of biology

- List of biological websites

- List of biologists

- List of biology topics

- List of omics topics in biology

- List of biology journals

- Outline of biology

- Reproduction

- Terminology of biology

- Periodic table of life sciences in Tinbergen's four questions

References

- ↑ Based on definition from: "Aquarena Wetlands Project glossary of terms". Texas State University at San Marcos. Archived from the original on 2004-06-08.

- ↑ "Life Science, Weber State Museum of Natural Science". Community.weber.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ "Who coined the term biology?". Info.com. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ↑ "biology". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Richards, Robert J. (2002). The Romantic Conception of Life: Science and Philosophy in the Age of Goethe. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-71210-9.

- ↑ Magner, Lois N. (2002). A History of the Life Sciences, Revised and Expanded. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-203-91100-6.

- ↑ Anthony Serafini (2013). The Epic History of Biology. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Theophrastus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Theophrastus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Fahd, Toufic (1996). "Botany and agriculture". In Morelon, Régis; Rashed, Roshdi. Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. 3. Routledge. p. 815. ISBN 0-415-12410-7.

- ↑ Magner, Lois N. (2002). A History of the Life Sciences, Revised and Expanded. CRC Press. pp. 133–144. ISBN 978-0-203-91100-6.

- ↑ Sapp, Jan (2003) Genesis: The Evolution of Biology, Ch. 7. Oxford University Press: New York. ISBN 0-19-515618-8

- ↑ Coleman, William (1977) Biology in the Nineteenth Century: Problems of Form, Function, and Transformation, Ch. 2. Cambridge University Press: New York. ISBN 0-521-29293-X

- ↑ Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, chapter 4

- ↑ Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, chapter 7

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2002. ISBN 0-674-00613-5. p. 187.

- ↑ Lamarck (1914)

- ↑ Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, chapter 10: "Darwin's evidence for evolution and common descent"; and chapter 11: "The causation of evolution: natural selection"

- ↑ Larson, Edward J. (2006). "Ch. 3". Evolution: The Remarkable History of a Scientific Theory. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-58836-538-5.

- ↑ Noble, Ivan (2003-04-14). "BBC NEWS | Science/Nature | Human genome finally complete". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-07-22.

- ↑ Mazzarello, P (1999). "A unifying concept: the history of cell theory". Nature Cell Biology. 1 (1): E13–E15. doi:10.1038/8964. PMID 10559875.

- ↑ De Duve, Christian (2002). Life Evolving: Molecules, Mind, and Meaning. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-19-515605-6.

- ↑ Futuyma, DJ (2005). Evolution. Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-187-3. OCLC 57311264.

- ↑ Packard, Alpheus Spring (1901). Lamarck, the founder of Evolution: his life and work with translations of his writings on organic evolution. New York: Longmans, Green. ISBN 0-405-12562-3.

- ↑ The Complete Works of Darwin Online – Biography. darwin-online.org.uk. Retrieved on 2006-12-15

- ↑ Dobzhansky, T. (1973). "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution". The American Biology Teacher. 35 (3): 125–129. doi:10.2307/4444260.

- ↑ As Darwinian scholar Joseph Carroll of the University of Missouri–St. Louis puts it in his introduction to a modern reprint of Darwin's work: "The Origin of Species has special claims on our attention. It is one of the two or three most significant works of all time—one of those works that fundamentally and permanently alter our vision of the world ... It is argued with a singularly rigorous consistency but it is also eloquent, imaginatively evocative, and rhetorically compelling." Carroll, Joseph, ed. (2003). On the origin of species by means of natural selection. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview. p. 15. ISBN 1-55111-337-6.

- ↑ Shermer p. 149.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species, John Murray.

- ↑ Simpson, George Gaylord (1967). The Meaning of Evolution (Second ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-00952-6.

- ↑ "Phylogeny". Bio-medicine.org. 2007-11-11. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ Marcial, Gene G. (August 13, 2007) From SemBiosys, A New Kind Of Insulin. businessweek.com

- ↑ Thanbichler M, Wang S, Shapiro L (2005). "The bacterial nucleoid: a highly organized and dynamic structure". J Cell Biochem. 96 (3): 506–21. doi:10.1002/jcb.20519. PMID 15988757.

- ↑ "Genotype definition – Medical Dictionary definitions". Medterms.com. 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ Raven, PH; Johnson, GB. (1999) Biology, Fifth Edition, Boston: Hill Companies, Inc. p. 1058. ISBN 0697353532.

- ↑ Rodolfo, Kelvin (2000-01-03) What is homeostasis? Scientific American.

- ↑ Bryant, D.A. & Frigaard, N.-U. (2006). "Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated". Trends Microbiol. 14 (11): 488–96. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001. PMID 16997562.

- ↑ Smith, A. L. (1997). Oxford dictionary of biochemistry and molecular biology. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. p. 508. ISBN 0-19-854768-4.

Photosynthesis – the synthesis by organisms of organic chemical compounds, esp. carbohydrates, from carbon dioxide using energy obtained from light rather than the oxidation of chemical compounds.

- ↑ Edwards, Katrina. Microbiology of a Sediment Pond and the Underlying Young, Cold, Hydrologically Active Ridge Flank. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

- ↑ Campbell, Neil A. & Reece, Jane B (2001). "6". Biology. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-6624-2. OCLC 47521441.

- ↑ Bartsch, John and Colvard, Mary P. (2009) The Living Environment. New York State Prentice Hall. ISBN 0133612023.

- ↑ "Molecular Biology – Definition". biology-online.org. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ Gray, Henry (1918) "Anatomy of the Human Body". 20th edition.

- ↑ Anthony J. F. Griffiths ... (2000). "Genetics and the Organism: Introduction". In Griffiths, Anthony J. F.; Miller, Jeffrey H.; Suzuki, David T.; Lewontin, Richard C.; Gelbart, William M. An Introduction to Genetic Analysis (7th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-3520-2.

- ↑ Hartl D, Jones E (2005). Genetics: Analysis of Genes and Genomes (6th ed.). Jones & Bartlett. ISBN 0-7637-1511-5.

- ↑ Brenner, S. (1974). "The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans". Genetics. 77 (1): 71–94. PMC 1213120

. PMID 4366476.

. PMID 4366476. - ↑ Sang, James H. (2001). "Drosophila melanogaster: The Fruit Fly". In Eric C. R. Reeve. Encyclopedia of genetics. USA: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, I. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-884964-34-3.

- ↑ Haffter P; Nüsslein-Volhard C (1996). "Large scale genetics in a small vertebrate, the zebrafish". Int. J. Dev. Biol. 40 (1): 221–7. PMID 8735932.

- ↑ Keller G (2005). "Embryonic stem cell differentiation: emergence of a new era in biology and medicine". Genes Dev. 19 (10): 1129–55. doi:10.1101/gad.1303605. PMID 15905405.

- ↑ Rensink WA, Buell CR (2004). "Arabidopsis to Rice. Applying Knowledge from a Weed to Enhance Our Understanding of a Crop Species". Plant Physiol. 135 (2): 622–9. doi:10.1104/pp.104.040170. PMC 514098

. PMID 15208410.

. PMID 15208410. - ↑ Coelho SM, Peters AF, Charrier B, et al. (2007). "Complex life cycles of multicellular eukaryotes: new approaches based on the use of model organisms". Gene. 406 (1–2): 152–70. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2007.07.025. PMID 17870254.

- ↑ Fields S, Johnston M (2005). "Cell biology. Whither model organism research?". Science. 307 (5717): 1885–6. doi:10.1126/science.1108872. PMID 15790833.

- ↑ Jablonski D (1999). "The future of the fossil record". Science. 284 (5423): 2114–16. doi:10.1126/science.284.5423.2114. PMID 10381868.

- ↑ Gillespie, John H. (1998) Population Genetics: A Concise Guide, Johns Hopkins Press. ISBN 0-8018-5755-4.

- ↑ Vassiliki Betta Smocovitis (1996) Unifying Biology: the evolutionary synthesis and evolutionary biology. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03343-9.

- ↑ Neill, Campbell (1996). Biology; Fourth edition. The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company. p. G-21 (Glossary). ISBN 0-8053-1940-9.

- ↑ Douglas, Futuyma (1998). Evolutionary Biology; Third edition. Sinauer Associates. p. 88. ISBN 0-87893-189-9.

- ↑ Margulis, L; Schwartz, KV (1997). Five Kingdoms: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth (3rd ed.). WH Freeman & Co. ISBN 978-0-7167-3183-2. OCLC 223623098.

- 1 2 Woese C, Kandler O, Wheelis M (1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 87 (12): 4576–9. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159

. PMID 2112744.

. PMID 2112744. - ↑ Rybicki EP (1990). "The classification of organisms at the edge of life, or problems with virus systematics". S Aft J Sci. 86: 182–186.

- ↑ McNeill, J.; Barrie, F.R.; Buck, W.R.; Demoulin, V.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Knapp, S.; Marhold, K.; Prado, J.; Prud'homme Van Reine, W.F.; Smith, G.F.; Wiersema, J.H.; Turland, N.J. (2012). International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code) adopted by the Eighteenth International Botanical Congress Melbourne, Australia, July 2011. Regnum Vegetabile 154. A.R.G. Gantner Verlag KG. ISBN 978-3-87429-425-6. Recommendation 60F

- ↑ Silyn-Roberts, Heather (2000). Writing for Science and Engineering: Papers, Presentation. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 198. ISBN 0-7506-4636-5.

- ↑ "ICTV Virus Taxonomy 2009". Ictvonline.org. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ Index of Viruses – Pospiviroidae (2006). In: ICTVdB – The Universal Virus Database, version 4. Büchen-Osmond, C (Ed), Columbia University, New York, USA. Version 4 is based on Virus Taxonomy, Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses, 8th ICTV Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Fauquet, CM, Mayo, MA, Maniloff, J, Desselberger, U, and Ball, LA (EDS) (2005) Elsevier/Academic Press, pp. 1259.

- ↑ Prusiner SB; Baldwin M; Collinge J; DeArmond SJ; Marsh R; Tateishi J; Weissmann C. "90. Prions – ICTVdB Index of Viruses". United States National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2009-08-27. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ Mayo MA; Berns KI; Fritsch C; Jackson AO; Leibowitz MJ; Taylor JM. "81. Satellites – ICTVdB Index of Viruses". United States National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2009-05-01. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ McNeill, John (1996-11-04). "The BioCode: Integrated biological nomenclature for the 21st century?". Proceedings of a Mini-Symposium on Biological Nomenclature in the 21st Century.

- ↑ "The Draft BioCode (2011)". International Committee on Bionomenclature (ICB).

- ↑ Greuter, W.; Garrity, G.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Jahn, R.; Kirk, P.M.; Knapp, S.; McNeill, J.; Michel, E.; Patterson, D.J.; Pyle, R.; Tindall, B.J. (2011). "Draft BioCode (2011): Principles and rules regulating the naming of organisms". Taxon. 60: 201–212.

- ↑ Hawksworth, David L. (2011). "Introducing the Draft BioCode (2011)". Taxon. 60: 199–200.

- ↑ Begon, M.; Townsend, C. R.; Harper, J. L. (2006). Ecology: From individuals to ecosystems. (4th ed.). Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-1117-8.

- ↑ Habitats of the world. New York: Marshall Cavendish. 2004. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-7614-7523-1.

- ↑ Black, J (2002). "Darwin in the world of emotions". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 95 (6): 311–3. doi:10.1258/jrsm.95.6.311. PMC 1279921

. PMID 12042386.

. PMID 12042386. - ↑ Gerstein, A. C.; Otto, S. P. (2006). "Why have sex? The population genetics of sex and recombination". Biochemical Society Transactions. 34 (4): 519–522. doi:10.1042/BST0340519. PMID 16856849.

- ↑ Agrawal, A. F. (2006). "Evolution of Sex: Why Do Organisms Shuffle Their Genotypes?". Current Biology. 16 (17): R696–R704. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.063. PMID 16950096.

- ↑ Bernstein, Harris; Bernstein, Carol and Michod, Richard E. (2011). "Meiosis as an Evolutionary Adaptation for DNA Repair". Chapter 19 in DNA Repair. Inna Kruman editor. InTech Open Publisher. doi:10.5772/25117

- ↑ Hörandl, Elvira (2013). Meiosis and the Paradox of Sex in Nature, Meiosis, Dr. Carol Bernstein (Ed.), ISBN 978-953-51-1197-9, InTech, doi:10.5772/56542.

- ↑ "Branches of Biology". Biology-online.org. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ "Biology on". Bellaonline.com. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

Further reading

- Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, A; Lewis, J; Raff, M; Roberts, K; Walter, P (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. OCLC 145080076.

- Begon, Michael; Townsend, CR; Harper, JL (2005). Ecology: From Individuals to Ecosystems (4th ed.). Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4051-1117-1. OCLC 57639896.

- Campbell, Neil (2004). Biology (7th ed.). Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8053-7146-X. OCLC 71890442.

- Colinvaux, Paul (1979). Why Big Fierce Animals are Rare: An Ecologist's Perspective (reissue ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02364-6. OCLC 10081738.

- Mayr, Ernst (1982). The Growth of Biological Thought: Diversity, Evolution, and Inheritance. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-36446-2.

- Hoagland, Mahlon (2001). The Way Life Works (reprint ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers inc. ISBN 0-7637-1688-X. OCLC 223090105.

- Janovy, John Jr. (2004). On Becoming a Biologist (2nd ed.). Bison Books. ISBN 0-8032-7620-6. OCLC 55138571.

- Johnson, George B. (2005). Biology, Visualizing Life. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 0-03-016723-X. OCLC 36306648.

- Tobin, Allan; Dusheck, Jennie (2005). Asking About Life (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 0-534-40653-X.

External links

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Biology |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Natural History and Biology |

| Look up biology in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiversity has learning materials about Biology at |

- Biology at DMOZ

- OSU's Phylocode

- Biology Online – Wiki Dictionary

- MIT video lecture series on biology

- Biology and Bioethics.

- Biological Systems – Idaho National Laboratory

- The Tree of Life: A multi-authored, distributed Internet project containing information about phylogeny and biodiversity.

- The Study of Biology

- Using the Biological Literature Web Resources

- Journal links

- PLos Biology A peer-reviewed, open-access journal published by the Public Library of Science

- Current Biology General journal publishing original research from all areas of biology

- Biology Letters A high-impact Royal Society journal publishing peer-reviewed Biology papers of general interest

- Science Magazine Internationally Renowned AAAS Science Publication – See Sections of the Life Sciences

- International Journal of Biological Sciences A biological journal publishing significant peer-reviewed scientific papers

- Perspectives in Biology and Medicine An interdisciplinary scholarly journal publishing essays of broad relevance

- Life Science Log