Xibe language

| Xibe | |

|---|---|

| ᠰᡞᠪᡝ ᡤᡞᠰᡠᠨ sibe gisun | |

| Pronunciation | [ɕivə kisun][1] |

| Native to | China |

| Region | Xinjiang[2] |

| Ethnicity | 190,000 Xibe people (2000)[3] |

Native speakers | 30,000 (2000)[3] |

|

Tungusic

| |

| Xibe script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

sjo |

| Glottolog |

xibe1242[4] |

The Xibe language (ᠰᡞᠪᡝ ᡤᡞᠰᡠᠨ sibe gisun, also Sibo, Sibe, Xibo language) is the most widely spoken of the Tungusic languages spoken by members of the ethnic group in Xinjiang, in the northwest of the People's Republic of China.

Classification

Xibe is conventionally viewed as a separate language within the southern group of Tungusic languages, alongside the more well-known Manchu language, having undergone more than 200 years of development separated from the Tungusic-speaking heartland since Xibe troops were dispatched to the Xinjiang frontiers in 1764. Some researchers such as Jerry Norman hold that Xibe is a dialect of Manchu, whereas other Xibologists, such as An Jun, argue that Xibe should be considered the "successor" to Manchu. Ethnohistorically, the Xibe people are not considered Manchu people, because they were excluded from chieftain Nurhaci's 17th-century tribal confederation to which the name "Manchu" was later applied.[5]

Phonology

Xibe is mutually intelligible with Manchu,[6] although unlike Manchu, Xibe is reported to have eight vowel distinctions as opposed to the six found in Manchu, as well as differences in morphology, and a more complex system of vowel harmony.[7]

Morphology

Xibe has 7 case morphemes, 3 of which are used quite differently from modern Manchu. The categorization of morphemes as case markers in spoken Xibe is partially controversial due to the status of numerous suffixes in the language. Despite the general controversy about the categorization of case markers versus postpositions in Tungusic languages, 4 case markers in Xibe are shared with literary Manchu (Nominative, Genitive, Dative-Locative and Accusative). Xibe's 3 innovated cases, the ablative, lative and instrumental-sociative share their meanings with similar case forms in neighboring Uyghur, Kazakh and Oiryat Mongolian.[8]

| Case Name | Suffix | Example | English Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -Ø | ɢazn-Ø | village |

| Genitive | -i | ɢazn-i | of the village |

| Dative-Locative | -də/-t | ɢazn-t | to the village |

| Accusative | -f/-və | ɢazn-əv | the village (object) |

| Ablative | -dəri | ġazn-dəri | from the village |

| Lative | -ći | ɢazn-ći | towards the village |

| Instrumental-Sociative | -maq | ɢazn-maq | with the village |

Lexicon

The general vocabulary and structure of Xibe has not been affected as much by Chinese as Manchu has. However, Xibe has absorbed a large body of Chinese sociological terminology, especially in politics: like gəming ("revolution", from 革命) and zhuxi ("chairperson", from 主席),[9] and economics: like chūna ("cashier", from 出纳) and daikuan ("loan", from 贷款). Written Xibe is more conservative and rejecting of loanwords, but spoken Xibe contains additional Chinese-derived vocabulary such as nan (from 男) for "man" where the Manchu-based equivalent is niyalma.[5] There has also been some influence from Russian,[10] including words such as konsul ("consul", from консул) and mashina ("sewing machine", from машина).[5] Smaller Xinjiang languages contribute mostly cultural terminology, such as namas ("an Islamic feast") from Uygur and baige ("horse race") from Kazakh.[5]

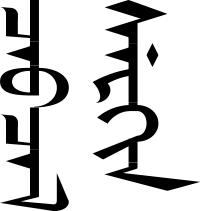

Writing system

Xibe is written in a script that derived from the Manchu alphabet.[7] The Xibe alphabet diverges from the Manchu alphabet in that the positions of the letters in some words have changed, Xibe lacks 13 out of 131 syllables in Manchu and Xibe has three syllables that are not found in Manchu (wi, wo, and wu).[5]

Cyrillization proposal

There was a proposal in China by 1957 to adapt the Cyrillic alphabet to Xibe, but this was abandoned in favor of the original Xibe script.[11]

| Cyrillic | Transliteration to Latin | IPA equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| А а | A a | a |

| Б б | B b | b |

| В в | V v | v |

| Г г | G g | g |

| Ғ ғ | G g, Gg gg | ɢ |

| Д д | D d | d |

| Е е | E e | ə |

| Ё ё | Ë ë, | œ |

| Ж ж | Dz Dz, Z z | dz |

| Җ җ | J j | dʐ, ʥ |

| З з | R' r', Ž ž | ʐ |

| И и | I i | i |

| Й й | Y y | y |

| К к | K k | k |

| Қ қ | K' k', Kk kk | q |

| Л л | L l | l |

| М м | M m | m |

| Н н | N n | n |

| Ң ң | Ng ng | ŋ |

| О о | O o | ɔ |

| Ө ө | O o | ø |

| П п | P p | p |

| Р р | R r | r |

| С с | S s | s |

| Т т | T t | t |

| У у | U u | u |

| Ү ү | W w | w |

| Ф ф | F f | f |

| Х х | H' h' | x |

| Ҳ ҳ | H h | χ |

| Ц ц | Ts ts, Z z | ʦ |

| Ч ч | C c | tʂ |

| Ш ш | Ś ś | ʂ |

| ы | E e | e, ɛ |

| Я я | Y y, Ya ya | j |

| ь | - | sign of thinness |

Table

See also: Manchu alphabet

This lists the letters in Xibe that differentiate it from Manchu as well as the placement of the letters. Red are important differences.

| Letters | Transliteration (Paul Georg von Mollendorf/Abkai/CMCD) | Unicode encoding | Description | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | Initial | Medial | Final | ||||

| ᡞ | ᡞ᠊ |

᠊ᡞ᠊ |

᠊ᡞ |

i | 185E | After the second row for vowels, third line used for k, g, h, b, p, after the fourth line for DZ | |

| ᠊ᡞ᠋᠊ | |||||||

| ᡞ᠌᠊ | ᠊ᡞ᠋ | ||||||

| ᠊ᡞ᠌ | |||||||

| ᠊ᡡ᠊ | ᠊ᡡ | ū/v/uu | 1861 | after k, g, h | |||

| ᡢ | ᡢ᠊ | ᠊ᡢ | ng | 1862 | only occurs at the end of the syllables | ||

| ᡣ | ᡣ᠊ |

᠊ᡣ᠊ |

k | 1863 | A, o, ū before first row, third row before e, I, u; at the end of syllables from the second row . | ||

| ᠊ᡣ᠋᠊ | ᠊ᡣ | ||||||

| ᡣ |

᠊ᡴ᠌᠊ |

||||||

| ᡪ᠊ |

᠊ᡪ᠊ |

j/j/zh | 186A | Only appear in the first syllable | |||

| ᠷ | ᠷ᠊ | ᠊ᠷ᠊ |

᠊ᠷ | r | 1837 | Native language does not have words beginning with r | |

| ᡫ | ᡫ᠊ | ᠊ᡫ᠊ | f | 186B | |||

| ᠸ | ᠸ᠊ |

᠊ᠸ᠊ |

w | 1838 | Can appear in a, e, i, o, u | ||

| ᡲ | ᡲ᠊ | ᠊ᡲ᠊ | j/j’’/zh | 1872 | jy is used for Chinese loanwords(Pinyinzhi) | ||

Usage

In 1998, there were eight primary schools that taught Xibe in the Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County, where the medium of instruction is Chinese but Xibe lessons are mandatory. From 1954 to 1959, the People's Publishing House in Ürümqi has published over 285 significant works, including government documents, belles-lettres, and school books, in Xibe.[5] Since 1946, the Xibe-language Qapqal News has been published in Yining. In Qapqal, Xibe-language programming is allocated 15 minutes per day of radio broadcasting and 15 to 30-minute television programmes broadcast one or twice per month.[12]

Xibe is taught as a second language by the Ili Normal University in the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture of northern Xinjiang; they established an undergraduate major in the language in 2005.[13] A few Manchu language enthusiasts from Eastern China have visited Qapqal Xibe County in order to experience an environment where a variety closely related to Manchu is spoken natively.[14]

Notes

- ↑ Li 1986, p. 1

- ↑ S. Robert Ramsey (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton University Press. pp. 216–. ISBN 0-691-01468-X.

- 1 2 Xibe at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Xibe". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gorelova, Liliya. "Past and Present of a Manchu Tribe: The Sibe". In Atabaki, Touraj; O'Kane, John. Post-Soviet Central Asia. Tauris Academic Studies. pp. 327–329.

- ↑ Gordon 2005, Xibe

- 1 2 Ramsey 1989, p. 215

- ↑ Zikmundova, Veronika (2013). Spoken Sibe: Morphology of the Inflected Parts of Speech. Prague: Karolinum Press. pp. 48–69.

- ↑ Ramsey 1989, p. 216

- ↑ Guo 2007

- ↑ Minglang Zhou. Multilingualism in China: the politics of writing reforms for minority languages. Berlin, 2003. ISBN 3-11-017896-6

- ↑ Zhang 2007

- ↑ 佟志红/Tong Zhihong (2007-06-06), "《察布查尔报》——锡伯人纸上的精神家园/'Qapqal News'—A 'Spiritual Homestead' on Paper for the Xibe People", 伊犁晚报/Yili Evening News, retrieved 2009-04-13

- ↑ Ian Johnson (2009-10-05), "In China, the Forgotten Manchu Seek to Rekindle Their Glory", The Wall Street Journal, retrieved 2009-10-05

References

- Li, Shulan (1986), 锡伯语简志/Outline of the Xibo language, Beijing: Nationalities Publishing House

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1989), The Languages of China, Princeton University Press

- 张莉/Zhang Li (2007), "新疆锡伯族新闻事业发展现状/Xinjiang Xibo Peoples' News Undertaking Present Situation", 伊犁师范学院学报/Journal of Ili Normal University (1), ISSN 1009-1076, retrieved 2009-04-13

- 郭庆/Guo Qing (2004), "俄罗斯语言文化对新疆锡伯族语言文化的影响/Influence of Russian Language and Culture on the Sibo Language and Culture in Xinjiang", 满语研究/Manchu Studies (2), ISSN 1000-7873, retrieved 2009-04-20

Further reading

- Jang, Taeho (2008), 锡伯语语法研究/Sibe Grammar, Kunming, China: Yunnan Minzu Chubanshe, ISBN 978-7-5367-4000-6

- Li, Shulan (1984), 锡伯语口语研究/Research into Xibo oral language, Beijing, China: Nationalities Publishing House, OCLC 298808366

- Kida, Akiyoshi (2000), A typological and Comparative study of Altaic languages with emphasis on XIBO Language: The part of XIBO Grammar

- Jin, Ning (1994), Phonological correspondences between literary Manchu and spoken Sibe, University of Washington

- Tong, Zhongming (2005), "俄国著名学者B·B·拉德洛夫用锡伯语复述记录的民间故事/The Folktales Retold and Recorded in Xibo Language by the Famous Russian Scholar B.B. Radloff", Studies of Ethnic Literature (3): 60–63, archived from the original on September 29, 2007

- Raimundo Veronika (2013), Spoken Sibe: Morphology of the Inflected Parts of Speech, Karolinum. ISBN 9788024621036

External links

| Xibe language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |