Dijon

| Dijon | ||

|---|---|---|

|

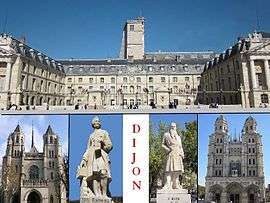

Top: Dijon City Hall, Bottom: Saint Benigne Cathedral, Statue of Jean-Philippe Rameau, Statue of Francois Rude, Saint Michel Church | ||

| ||

Dijon | ||

|

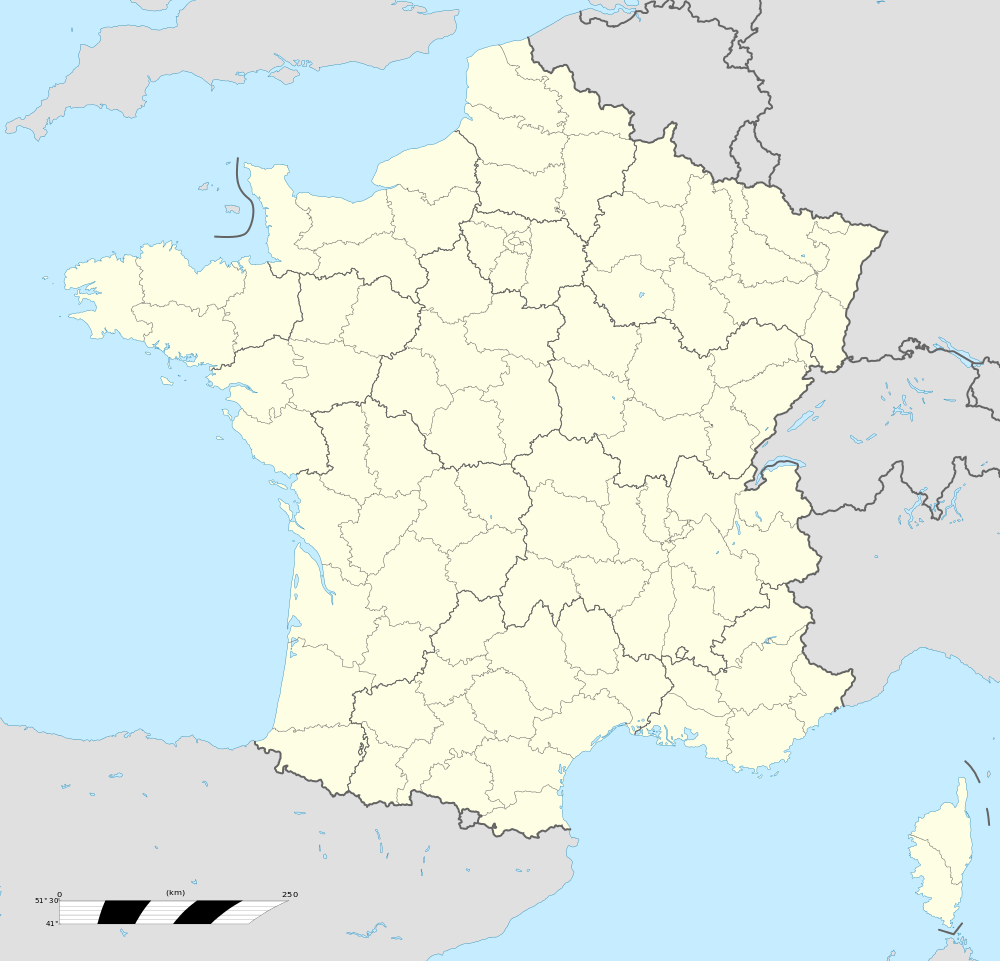

Location within Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region  Dijon | ||

| Coordinates: 47°17′26″N 5°02′34″E / 47.2906°N 5.0428°ECoordinates: 47°17′26″N 5°02′34″E / 47.2906°N 5.0428°E | ||

| Country | France | |

| Region | Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | |

| Department | Côte-d'Or | |

| Arrondissement | Dijon | |

| Intercommunality | Dijon | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor (2015–2020) | François Rebsamen | |

| Area1 | 40.41 km2 (15.60 sq mi) | |

| Population (2012)2 | 152,071 | |

| • Density | 3,800/km2 (9,700/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| INSEE/Postal code | 21231 / 21000 | |

| Elevation |

220–410 m (720–1,350 ft) (avg. 245 m or 804 ft) | |

| Website | http://www.dijon.fr/ | |

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | ||

Dijon (French pronunciation: [diʒɔ̃]) is a city in eastern France, capital of the Côte-d'Or département and of the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region.

The earliest archaeological finds within the city limits of Dijon date to the Neolithic period. Dijon later became a Roman settlement named Divio, located on the road from Lyon to Paris. The province was home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th centuries and Dijon was a place of tremendous wealth and power, one of the great European centres of art, learning and science. Population (2008): 151,576 within the city limits; 250,516 (2007) for the greater Dijon area.

The city has retained varied architectural styles from many of the main periods of the past millennium, including Capetian, Gothic and Renaissance. Many still-inhabited town houses in the city's central district date from the 18th century and earlier. Dijon architecture is distinguished by, among other things, toits bourguignons (Burgundian polychrome roofs) made of tiles glazed in terracotta, green, yellow and black and arranged in geometric patterns.

Dijon holds an International and Gastronomic Fair every year in autumn. With over 500 exhibitors and 200,000 visitors every year, it is one of the ten most important fairs in France. Dijon is also home, every three years, to the international flower show Florissimo. Dijon is famous for Dijon mustard which originated in 1856, when Jean Naigeon of Dijon substituted verjuice, the acidic "green" juice of not-quite-ripe grapes, for vinegar in the traditional mustard recipe.

The historical center of the city has been registered since July 4, 2015 as a UNESCO World Heritage site.[1]

History

The earliest archaeological finds within the city limits of Dijon date to the Neolithic period. Dijon later became a Roman settlement called Divio, which may mean sacred fountain, located on the road from Lyon to Paris. Saint Benignus, the city's apocryphal patron saint, is said to have introduced Christianity to the area before being martyred.

This province was home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century, and Dijon was a place of tremendous wealth and power and one of the great European centres of art, learning, and science. The Duchy of Burgundy was a key in the transformation of medieval times toward early modern Europe. The Palace of the Dukes of Burgundy now houses city hall and a museum of art.

In 1513, Swiss and Imperial armies invaded Burgundy and besieged Dijon, which was defended by the governor of the province, Louis II de la Trémoille. The siege was extremely violent, but the town succeeded in resisting the invaders. After long negotiations, Louis II de la Trémoille managed to persuade the Swiss and the Imperial armies to withdraw their troops and also to return three hostages who were being held in Switzerland. During the siege, the population called on the Virgin Mary for help and saw the town's successful resistance and the subsequent withdrawal of the invaders as a miracle. For those reasons, in the years following the siege the inhabitants of Dijon began to venerate Notre-Dame de Bon-Espoir (Our Lady of Good Hope). Although a few areas of the town were destroyed, there are nearly no signs of the siege of 1513 visible today. However, Dijon's museum of fine arts has a large tapestry depicting this episode in the town's history: it shows the town before all subsequent destruction (particularly that which occurred during the French Revolution) and is an example of 16th-century art.

Dijon was also occupied by anti-Napoleonic coalitions in 1814, by the Prussian army in 1870–71, and by Nazi Germany beginning in June 1940, during WWII, when it was bombed by US Air Force B-17 Flying Fortresses,[2] before the liberation of Dijon by the French Army and the French Resistance, 11 September 1944.

Geography

Dijon is situated at the heart of a plain drained by two small converging rivers: the Suzon, which crosses it mostly underground from north to south, and the Ouche, on the southern side of town. Farther south is the côte, or hillside, of vineyards that gives the department its name. Dijon lies 310 km (193 mi) southeast of Paris, 190 km (118 mi) northwest of Geneva, and 190 km (118 mi) north of Lyon.

Climate

The average low of winter is −1 °C (30 °F), with an average high of 4.2 °C (39.6 °F). The average high of summer is 25.3 °C (77.5 °F) with an average low of 14.7 °C (58.5 °F). Average normal temperatures are between 2.3 °C (36.1 °F) and 5.3 °C (41.5 °F) from November to March, and 17.2 to 19.7 °C (63.0 to 67.5 °F) from June to August.[3] The climate is oceanic but with a greater temperature range than closer to the Atlantic coastline.

| Climate data for Dijon (1981–2010 averages) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

29.0 (84.2) |

34.4 (93.9) |

36.0 (96.8) |

38.6 (101.5) |

39.3 (102.7) |

34.2 (93.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

39.3 (102.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

15.2 (59.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.2 (73.8) |

26.1 (79) |

25.6 (78.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

3.3 (37.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

17.8 (64) |

20.3 (68.5) |

19.9 (67.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

2.9 (37.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.8 (30.6) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.4 (45.3) |

2.8 (37) |

0.3 (32.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −20.5 (−4.9) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−15.3 (4.5) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.8 (33.4) |

2.8 (37) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−20.8 (−5.4) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 57.4 (2.26) |

43.8 (1.724) |

48.3 (1.902) |

58.2 (2.291) |

86.6 (3.409) |

68.1 (2.681) |

66.0 (2.598) |

60.1 (2.366) |

64.5 (2.539) |

70.9 (2.791) |

73.2 (2.882) |

63.4 (2.496) |

760.5 (29.941) |

| Average precipitation days | 10.9 | 8.5 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 11.3 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 115.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 82 | 76 | 71 | 74 | 72 | 68 | 71 | 78 | 85 | 87 | 89 | 78.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 63.9 | 94.4 | 151.3 | 185.4 | 212.3 | 239.1 | 248.3 | 233.6 | 181.3 | 117.2 | 67.8 | 54.2 | 1,848.8 |

| Source #1: Météo France[4][5] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity, 1961–1990)[6] | |||||||||||||

Sights

Dijon has a large number of churches, including Notre Dame de Dijon, St. Philibert, St. Michel, and Dijon Cathedral, dedicated to the apocryphal Saint Benignus, the crypt of which is over 1,000 years old. The city has retained varied architectural styles from many of the main periods of the past millennium, including Capetian, Gothic and Renaissance. Many still-inhabited town houses in the city's central district date from the 18th century and earlier. Dijon architecture is distinguished by, among other things, toits bourguignons (Burgundian polychrome roofs) made of tiles glazed in terracotta, green, yellow and black and arranged in geometric patterns.

Dijon was largely spared the destruction of wars such as the 1870 Franco-Prussian War and the Second World War, despite the city being occupied. Therefore, many of the old buildings such as the half-timbered houses dating from the 12th to the 15th centuries (found mainly in the city's core district) are undamaged, at least by organized violence.

Dijon is home to many museums, including the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon in part of the Ducal Palace (see below). It contains, among other things, ducal kitchens dating back to the mid-15th century, and a substantial collection of primarily European art, from Roman times through the present.

Among the more popular sights is the Ducal Palace, the Palais des Ducs et des États de Bourgogne or "Palace of the Dukes and the States of Burgundy" (47°19′19″N 5°2′29″E / 47.32194°N 5.04139°E), which includes one of only a few remaining examples of Capetian period architecture in the region.

The church of Notre Dame is famous for both its art and architecture. Popular legend has it that one of its stone relief sculptures, an owl (la chouette) is a good-luck charm: visitors to the church touch the owl with their left hands to make a wish. (The current carving was restored after it was damaged by vandalism in the night of 5 and 6 January 2001).

The Grand Théâtre de Dijon, built in 1828 and one of the main performing venues of the Opéra de Dijon, was declared a monument historique of France in 1975. It was designed by the Dijon-born architect Jacques Cellerier (1742–1814) in the Neo-classical style with an interior modelled on Italian opera houses.[7]

Transport

Dijon is located approximately 300 km (190 mi) southeast of Paris, about three hours by car along the A38 and A6 motorways. The A31 provides connections to Nancy, Lille and Lyon. The A39 connects Dijon with Bourg-en-Bresse and Geneva, the A36 with Mulhouse and Basel.

Dijon is an important railway junction for lines from Paris to Lyon and Marseille, and the east-west lines to Besançon, Belfort, Nancy, Switzerland, and Italy. The Gare de Dijon-Ville is the main railway station, providing service to Paris-Gare de Lyon by TGV high-speed train (LGV Sud-Est), covering the 300 km (190 mi) in one hour and 40 minutes. For comparison, Lyon is 180 km (110 mi) away and two hours distant by standard train. The city of Nice takes about six hours by TGV and Strasbourg only 1 hour and 56 minutes via the TGV Rhin-Rhône. Lausanne in Switzerland is less than 150 km (93 mi) away or two hours by train. Numerous regional TER Bourgogne trains depart from the same station.

A new tram system opened in September 2012. Line T1 is an 8.5 kilometres (5.3 miles) line with 16 stations running west-east from the Dijon railway station to Quetigny.[8] Line T2 opened in December 2012, an 11.5 km (7.1 miles) north-south line with 21 stations running between Valmy and Chenôve.

Culture

Dijon holds its International and Gastronomic Fair every year in autumn. With over 500 exhibitors and 200,000 visitors every year, it is one of the ten most important fairs in France. Dijon is also home, every three years, to the international flower show Florissimo.

Dijon has numerous museums such as the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, the Musée Archéologique, the Musée de la Vie Bourguignonne, the Musée d'Art Sacré, and the Musée Magnin. It also contains approximately 700 hectares of parks and green space, including the Jardin botanique de l'Arquebuse.

Apart from the numerous bars, which sometimes have live bands, some popular music venues in Dijon are : Le zenith de Dijon, La Vapeur and l'Atheneum.

Dijon mustard originated in 1856, when Jean Naigeon of Dijon substituted verjuice, the acidic "green" juice of not-quite-ripe grapes, for vinegar in the traditional mustard recipe.[9] In general, mustards from Dijon today contain white wine rather than verjuice. Dijon mustard is not necessarily produced near Dijon, as the term is regarded as genericized under European Union law, so that it cannot be registered for protected designation of origin status.[10] Most Dijon mustard (brands such as Amora or Maille) is produced industrially and over 90% of mustard seed used in local production is imported, mainly from Canada. In 2008, Unilever closed its Amora mustard factory in Dijon. Dijon mustard shops sell exotic or unusually-flavoured mustard (fruit-flavoured, for example), often sold in decorative hand-painted faience (china) pots.

Burgundy is a world-famous wine growing region, and notable vineyards, such as Vosne-Romanée and Gevrey-Chambertin, are within 20 minutes of the city center. The town's university boasts a renowned oenology institute. The road from Santenay to Dijon is known as the "route des Grands Crus", where eight of the world's top ten most expensive wines are produced, according to Wine Searcher.[11]

The city is also well known for its crème de cassis, or blackcurrant liqueur, used in the drink known as "Kir", named after former mayor of Dijon canon Félix Kir, a mixture of crème de cassis with white wine, traditionally Bourgogne aligoté.

Dijon is home to Dijon FCO, a Football team now in Ligue 1. Dijon has its own basketball club (Pro A), JDA Dijon Basket. Dijon is home to the Dijon Ducs ice hockey team, who play in the Magnus League.[12] To the northwest, the race track of Dijon-Prenois hosts various motor sport events. It hosted the Formula 1 French Grand Prix on five occasions from 1974 to 1984.

Colleges and universities

- Dijon hosts the main campus of the University of Burgundy

- École nationale des beaux-arts de Dijon

- European Campus of Sciences Po Paris

- Agrosup Dijon

Population

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1793 | 20,760 | — |

| 1800 | 18,888 | −9.0% |

| 1806 | 22,026 | +16.6% |

| 1821 | 22,397 | +1.7% |

| 1831 | 25,352 | +13.2% |

| 1836 | 24,817 | −2.1% |

| 1841 | 26,184 | +5.5% |

| 1846 | 27,543 | +5.2% |

| 1851 | 32,253 | +17.1% |

| 1856 | 33,493 | +3.8% |

| 1861 | 37,074 | +10.7% |

| 1866 | 39,193 | +5.7% |

| 1872 | 42,573 | +8.6% |

| 1876 | 47,939 | +12.6% |

| 1881 | 55,453 | +15.7% |

| 1886 | 60,855 | +9.7% |

| 1891 | 65,428 | +7.5% |

| 1896 | 67,736 | +3.5% |

| 1901 | 71,326 | +5.3% |

| 1906 | 74,113 | +3.9% |

| 1911 | 76,847 | +3.7% |

| 1921 | 78,578 | +2.3% |

| 1926 | 83,815 | +6.7% |

| 1931 | 90,869 | +8.4% |

| 1936 | 96,257 | +5.9% |

| 1946 | 100,664 | +4.6% |

| 1954 | 112,844 | +12.1% |

| 1962 | 135,694 | +20.2% |

| 1968 | 145,357 | +7.1% |

| 1975 | 151,705 | +4.4% |

| 1982 | 140,942 | −7.1% |

| 1990 | 146,703 | +4.1% |

| 1999 | 150,138 | +2.3% |

| 2006 | 151,504 | +0.9% |

| 2009 | 152,110 | +0.4% |

Personalities

- John the Fearless (1371–1419), Duke of Burgundy

- Charles the Bold (1433–1477), Duke of Burgundy

- Jean Le Fèvre (canon) (1493–1565), lexicographer

- Edmond Debeaumarché (1906–1959), a hero of the French Resistance

- Christian Allard (b. 1964), Member of the Scottish Parliament[13]

- Jean-Marc Boivin (1951–1990), extreme sports specialist

- Antoine Bret (1717–1792), French playwright

- Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627–1704), bishop and theologist

- Madjid Bougherra (b. 1982), Rangers F.C. footballer

- Augustin Cauchy (1789–1867), mathematician

- Laurent Chambertin (b. 1966), volleyball player

- Jane Frances de Chantal (Jeanne – Françoise Frémiot, baronne de Chantal, 1572–1641), founder of the Visitation Order

- François Chaussier (1746–1828), physician

- Anne-Caroline Chausson (b. 1977), Olympic medalist in cycling

- Bernard Courtois (1777–1838), discoverer of the element iodine

- Charles Joseph Minard (1781-1870), civil engineer & first information graphics

- Henry Darcy (1803–1858), engineer

- Jean-Jacques-Joseph Debillemont (1824–1879), conductor and operetta composer

- Alexandre Gustave Eiffel (1832–1923), engineer and architect

- Roger Guillemin (b. 1924), Nobel laureate in Physiology and Medicine

- Claude Jade (1948–2006), actress

- Joseph Jacotot (1770–1840), educational philosopher

- François Jouffroy (1806–1882), sculptor

- Henri Legrand du Saulle (1830–1886), psychiatrist

- Jean-Pierre Marielle (b. 1932), actor

- Julien Pillet (b. 1977), Olympic medalist in sabre fencer

- Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764), composer

- François Rude (1784–1855), sculptor

- Elizabeth of the Trinity (Marie – Élisabeth Catez, 1880–1906), Carmelite nun and religious writer

- Vitalic (born as Pascal Arbez in 1976), an electronic music artist

Twin towns and sister cities

Dijon is twinned with:[14][15]

See also

References

- ↑ Climates of Burgundy.

- ↑ "Bombing of Dijon, France". U.S. Air Force. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ↑ HKO August 2011, weather.gov.hk

- ↑ "Données climatiques de la station de Dijon" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Climat Bourgogne" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Normes et records 1961-1990: Dijon-Longvic (21) - altitude 219m" (in French). Infoclimat. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ↑ Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication de France. Monuments historiques: Théâtre: Bourgogne, Côte-d'Or, Dijon. Retrieved 10 March 2015 (French).

- ↑ "Pioneering PPP energises Dijon tram". Railway Gazette. 21 July 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ Jack E. Staub, Ellen Buchert (18 August 2008). 75 Exceptional Herbs for Your Garden. Gibbs Smith. p. 170.

- ↑ "SCADPlus: Protection of Geographical Indications and Designations of Origin". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ↑ "World's Top 50 Most Expensive Wines". Wine-Searcher. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ↑ Dijon Hockey Club. "Duc's Official Website" (in French). Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ↑ Christian Allard – MSPs : Scottish Parliament

- ↑ "Ville de Dijon – Dijon, une politique renouvelée à l'international". Dijon.fr. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Ville de Dijon – Jumelages". Dijon.fr. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Sister Cities". Dallas-ecodev.org. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "Opole Official Website – Twin Towns".

(in English and Polish)2007–2009 Urząd Miasta Opola. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

(in English and Polish)2007–2009 Urząd Miasta Opola. Retrieved 18 June 2009. - ↑ "Skopje – Twin towns & Sister cities". Official portal of City of Skopje. Grad Skopje – 2006 – 2013, www.skopje.gov.mk. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ↑ Friendly relationship at Official website of Volgograd

- ↑ "Vennskapsbyer". www.visitvolgograd.info. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ↑ "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ "Toluca twinned with Dijon". SINTESIS INFORMATICA MUNICIPAL. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ Korolczuk, Dariusz (12 January 2010). "Foreign cooperation – Partner Cities". Białystok City Council. City Office in Białystok. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Nanchang City and Sister Cities Intercommunion". Nanchang Municipal Party Committee of the CPC and Nanchang Municipal Government. Nanchang Economic Information Center. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

Further reading

- Published in the 19th century

- "Dijon", A handbook for travellers in France, London: John Murray, 1861

- C.B. Black (1876), "Dijon", Guide to the north of France, Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black

- "Dijon", Northern France, Leipsic: Karl Baedeker, 1899, OCLC 2229516

- Published in the 20th century

- "Dijon", The Encyclopaedia Britannica (11th ed.), New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1910, OCLC 14782424

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dijon. |

Dijon travel guide from Wikivoyage

Dijon travel guide from Wikivoyage "Dijon". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). 1911.

"Dijon". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). 1911.- Official website (French)

- Dijon tourist office

.svg.png)

_-_001.jpg)