Hindu texts

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

|

Rig vedic

Sama vedic Yajur vedic Atharva vedic |

|

Other scriptures |

| Related Hindu texts |

|

|

|

Timeline |

Hindu texts are manuscripts and historic literature related to any of the diverse traditions within Hinduism. A few texts are shared resources across these traditions and broadly considered as Hindu scriptures.[1][2] These include the Vedas and the Upanishads. Scholars hesitate in defining the term "Hindu scripture" given the diverse nature of Hinduism,[2][3] many include Bhagavad Gita and Agamas as Hindu scriptures,[2][3][4] while Dominic Goodall includes Bhagavata Purana and Yajnavalkya Smriti to the list of Hindu scriptures.[2]

There are two historic classifications of Hindu texts: Shruti – that which is heard,[5] and Smriti – that which is remembered.[6] The Śruti refers to the body of most authoritative, ancient religious texts, without any author, comprising the central canon of Hinduism.[5] It includes the four Vedas including its four types of embedded texts - the Samhitas, the Brahmanas, the Aranyakas and the early Upanishads.[7] Of the Shrutis (Vedic corpus), the Upanishads alone are widely influential among Hindus, considered scriptures par excellence of Hinduism, and their central ideas have continued to influence its thoughts and traditions.[8][9]

The Smriti texts are a specific body of Hindu texts attributed to an author,[7] as a derivative work they are considered less authoritative than Sruti in Hinduism.[6] The Smrti literature is a vast corpus of diverse texts, and includes but is not limited to Vedāngas, the Hindu epics, the Sutras and Shastras, the texts of Hindu philosophies, the Puranas, the Kāvya or poetical literature, the Bhasyas, and numerous Nibandhas (digests) covering politics, ethics, culture, arts and society.[10][11]

Many ancient and medieval Hindu texts were composed in Sanskrit, many others in regional Indian languages. In modern times, most ancient texts have been translated into other Indian languages and some in Western languages.[2] Prior to the start of the common era, the Hindu texts were composed orally, then memorized and transmitted orally, from one generation to next, for more than a millennia before they were written down into manuscripts.[12][13] This verbal tradition of preserving and transmitting Hindu texts, from one generation to next, continued into the modern era.[12][13]

The Vedas

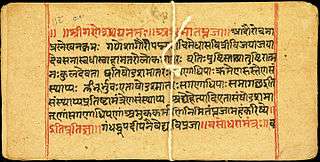

_Manuscript_LACMA_M.71.1.33.jpg)

The Vedas are a large body of Hindu texts originating in ancient India, before about 300 BCE. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the oldest layer of Sanskrit literature and the oldest scriptures of Hinduism.[14][15][16] Hindus consider the Vedas to be apauruṣeya, which means "not of a man, superhuman"[17] and "impersonal, authorless".[18][19][20]

Vedas are also called śruti ("what is heard") literature,[21] distinguishing them from other religious texts, which are called smṛti ("what is remembered"). The Veda, for orthodox Indian theologians, are considered revelations, some way or other the work of the Deity.[22] In the Hindu Epic the Mahabharata, the creation of Vedas is credited to Brahma.[23]

There are four Vedas: the Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Samaveda and the Atharvaveda.[24][25] Each Veda has been subclassified into four major text types – the Samhitas (mantras and benedictions), the Aranyakas (text on rituals, ceremonies, sacrifices and symbolic-sacrifices), the Brahmanas (commentaries on rituals, ceremonies and sacrifices), and the Upanishads (text discussing meditation, philosophy and spiritual knowledge).[24][26][27]

The Upanishads

The Upanishads are a collection of Hindu texts which contain some of the central philosophical concepts of Hinduism.[28][note 1]

The Upanishads are commonly referred to as Vedānta, variously interpreted to mean either the "last chapters, parts of the Veda" or "the object, the highest purpose of the Veda".[29] The concepts of Brahman (Ultimate Reality) and Ātman (Soul, Self) are central ideas in all the Upanishads,[30][31] and "Know your Ātman" their thematic focus.[31] The Upanishads are the foundation of Hindu philosophical thought and its diverse traditions.[9][32] Of the Vedic corpus, they alone are widely known, and the central ideas of the Upanishads have had a lasting influence on Hindu philosophy.[8][9]

More than 200 Upanishads are known, of which the first dozen or so are the oldest and most important and are referred to as the principal or main (mukhya) Upanishads.[33][34] The mukhya Upanishads are found mostly in the concluding part of the Brahmanas and Aranyakas[35] and were, for centuries, memorized by each generation and passed down verbally. The early Upanishads all predate the Common Era, some in all likelihood pre-Buddhist (6th century BCE),[36] down to the Maurya period.[37] Of the remainder, some 95 Upanishads are part of the Muktika canon, composed from about the start of common era through medieval Hinduism. New Upanishads, beyond the 108 in the Muktika canon, continued to being composed through the early modern and modern era, though often dealing with subjects unconnected to Hinduism.[38][39]

Post-Vedic texts

The texts that appeared afterwards were called smriti. Smriti literature includes various Shastras and Itihasas (epics like Ramayana, Mahabharata), Harivamsa Puranas, Agamas and Darshanas.

The Sutras and Shastras texts were compilations of technical or specialized knowledge in a defined area. The earliest are dated to later half of the 1st millennium BCE. The Dharma-shastras (law books), derivatives of the Dharma-sutras. Other examples were bhautikashastra "physics", rasayanashastra "chemistry", jīvashastra "biology", vastushastra "architectural science", shilpashastra "science of sculpture", arthashastra "economics" and nītishastra "political science".[40] It also includes Tantra and Agama literature.[41]

This genre of texts includes the Sutras and Shastras of the six schools of Hindu philosophy.[42][43]

The Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita is a 700–verse Hindu scripture that is part of the ancient Sanskrit epic Mahabharata. This scripture contains a conversation between Pandava prince Arjuna and his guide Krishna on a variety of philosophical issues. Commentators see the setting of the Gita in a battlefield as an allegory for the ethical and moral struggles of the human life. The Bhagavad Gita's call for selfless action inspired many leaders of the Indian independence movement including Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who referred to the Gita as his "spiritual dictionary". Numerous commentaries have been written on the Bhagavad Gita with widely differing views on the essentials, beginning with Adi Sankara's commentary on the Gita in the 8th century CE.

The Puranas

The Puranas are a vast genre of Hindu texts that encyclopedically cover a wide range of topics, particularly myths, legends and other traditional lore.[44] Composed primarily in Sanskrit, but also in regional languages,[45][46] several of these texts are named after major Hindu deities such as Vishnu, Shiva and Devi.[47][48]

There are 18 Maha Puranas (Great Puranas) and 18 Upa Puranas (Minor Puranas),[49] with over 400,000 verses.[44] The Puranas do not enjoy the authority of a scripture in Hinduism,[49] but are considered a Smriti.[50] These Hindu texts have been influential in the Hindu culture, inspiring major national and regional annual festivals of Hinduism.[51] The Bhagavata Purana has been among the most celebrated and popular text in the Puranic genre.[52][53]

The Tevaram Saivite hymns

The Tevaram is a body of remarkable hymns exuding Bhakti composed more than 1400–1200 years ago in the classical Tamil language by three Saivite composers. They are credited with igniting the Bhakti movement in the whole of India.

Divya Prabandha Vaishnavite hymns

The Nalayira Divya Prabandha (or Nalayira (4000) Divya Prabhamdham) is a divine collection of 4,000 verses (Naalayira in Tamil means 'four thousand') composed before 8th century AD [1], by the 12 Alvars, and was compiled in its present form by Nathamuni during the 9th – 10th centuries. The Alvars sung these songs at various sacred shrines. These shrines are known as the Divya Desams.

In South India, especially in Tamil Nadu, the Divya Prabhandha is considered as equal to the Vedas, hence the epithet Dravida Veda. In many temples, Srirangam, for example, the chanting of the Divya Prabhandham forms a major part of the daily service. Prominent among the 4,000 verses are the 1,100+ verses known as the Thiru Vaaymozhi, composed by Nammalvar (Kaaril Maaran Sadagopan) of Thiruk Kurugoor.

Other Hindu texts

Ancient and medieval era Hindu texts for specific fields, in Sanskrit and other regional languages, have been reviewed as follows,

| Field | Reviewer | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture and food | Gyula Wojtilla | [54] |

| Architecture | P Acharya, B Dagens | [55][56] |

| Devotionalism | Karen Pechelis | [57] |

| Drama, dance and performance arts | AB Keith, Rachel Baumer and James Brandon, Mohan Khokar | [58][59][60] |

| Education, school system | Hartmut Scharfe | [61] |

| Epics | John Brockington | [62] |

| Gnomic and didactic literature | Ludwik Sternbach | [63] |

| Grammar | Hartmut Scharfe | [64] |

| Law and jurisprudence | J Duncan M Derrett | [65] |

| Lexicography | Claus Vogel | [66] |

| Mathematics and exact sciences | Kim Plofker David Pingree | [67][68] |

| Medicine | MS Valiathan, Kenneth Zysk | [69][70] |

| Music | Emmie te Nijenhuis, Lewis Rowell | [71][72] |

| Mythology | Ludo Rocher | [73] |

| Philosophy | Karl Potter | [74] |

| Poetics | Edwin Gerow, Siegfried Lienhard | [75] |

| Gender and Sex | Johann Jakob Meyer | [76] |

| State craft, politics | Patrick Olivelle | [77] |

| Tantrism, Agamas | Teun Goudriaan | [78] |

| Temples, Sculpture | Stella Kramrisch | [79] |

| Scriptures (Vedas and Upanishads) | Jan Gonda | [80] |

See also

- Hindu Epics

- List of Hindu scriptures

- List of historic Indian texts

- List of sutras

- Sanskrit literature

Notes

References

- ↑ Frazier, Jessica (2011), The Continuum companion to Hindu studies, London: Continuum, ISBN 978-0-8264-9966-0, pages 1–15

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-20778-3, page ix-xliii

- 1 2 Klaus Klostermaier (2007), A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4, pages 46–52, 76–77

- ↑ RC Zaehner (1992), Hindu Scriptures, Penguin Random House, ISBN 978-0-679-41078-2, pages 1–11 and Preface

- 1 2 James Lochtefeld (2002), "Shruti", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N–Z, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8, page 645

- 1 2 James Lochtefeld (2002), "Smrti", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N–Z, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8, page 656–657

- 1 2 Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty (1988), Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-1867-6, pages 2–3

- 1 2 Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanisads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-535242-9, page 3; Quote: "Even though theoretically the whole of vedic corpus is accepted as revealed truth [shruti], in reality it is the Upanishads that have continued to influence the life and thought of the various religious traditions that we have come to call Hindu. Upanishads are the scriptures par excellence of Hinduism".

- 1 2 3 Wendy Doniger (1990), Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism, 1st Edition, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-61847-0, pages 2–3; Quote: "The Upanishads supply the basis of later Hindu philosophy; they alone of the Vedic corpus are widely known and quoted by most well-educated Hindus, and their central ideas have also become a part of the spiritual arsenal of rank-and-file Hindus."

- ↑ Purushottama Bilimoria (2011), The idea of Hindu law, Journal of Oriental Society of Australia, Vol. 43, pages 103–130

- ↑ Roy Perrett (1998), Hindu Ethics: A Philosophical Study, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2085-5, pages 16–18

- 1 2 Michael Witzel, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood, Gavin, ed. (2003), The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., ISBN 1-4051-3251-5, pages 68–71

- 1 2 William Graham (1993), Beyond the Written Word: Oral Aspects of Scripture in the History of Religion, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-44820-8, pages 67–77

- ↑ see e.g. MacDonell 2004, pp. 29–39; Sanskrit literature (2003) in Philip's Encyclopedia. Accessed 2007-08-09

- ↑ see e.g. Radhakrishnan & Moore 1957, p. 3; Witzel, Michael, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood 2003, p. 68; MacDonell 2004, pp. 29–39; Sanskrit literature (2003) in Philip's Encyclopedia. Accessed 2007-08-09

- ↑ Sanujit Ghose (2011). "Religious Developments in Ancient India" in Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Vaman Shivaram Apte, The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary, see apauruSeya

- ↑ D Sharma, Classical Indian Philosophy: A Reader, Columbia University Press, pages 196–197

- ↑ Jan Westerhoff (2009), Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538496-3, page 290

- ↑ Warren Lee Todd (2013), The Ethics of Śaṅkara and Śāntideva: A Selfless Response to an Illusory World, ISBN 978-1-4094-6681-9, page 128

- ↑ Apte 1965, p. 887

- ↑ Müller 1891, pp. 17–18

- ↑ Seer of the Fifth Veda: Kr̥ṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vyāsa in the Mahābhārata Bruce M. Sullivan, Motilal Banarsidass, pages 85–86

- 1 2 Gavin Flood (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0, pages 35–39

- ↑ Bloomfield, M. The Atharvaveda and the Gopatha-Brahmana, (Grundriss der Indo-Arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde II.1.b.) Strassburg 1899; Gonda, J. A history of Indian literature: I.1 Vedic literature (Samhitas and Brahmanas); I.2 The Ritual Sutras. Wiesbaden 1975, 1977

- ↑ A Bhattacharya (2006), Hindu Dharma: Introduction to Scriptures and Theology, ISBN 978-0-595-38455-6, pages 8–14; George M. Williams (2003), Handbook of Hindu Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2, page 285

- ↑ Jan Gonda (1975), Vedic Literature: (Saṃhitās and Brāhmaṇas), Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-01603-2

- 1 2 Olivelle 1998, p. xxiii.

- ↑ Max Muller, The Upanishads, Part 1, Oxford University Press, page LXXXVI footnote 1

- ↑ Mahadevan 1956, p. 59.

- 1 2 PT Raju (1985), Structural Depths of Indian Thought, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-139-4, pages 35–36

- ↑ Wiman Dissanayake (1993), Self as Body in Asian Theory and Practice (Editors: Thomas P. Kasulis et al.), State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1080-6, page 39; Quote: "The Upanishads form the foundations of Hindu philosophical thought and the central theme of the Upanishads is the identity of Atman and Brahman, or the inner self and the cosmic self.";

Michael McDowell and Nathan Brown (2009), World Religions, Penguin, ISBN 978-1-59257-846-7, pages 208–210 - ↑ Stephen Phillips (2009), Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-14485-8, Chapter 1

- ↑ E Easwaran (2007), The Upanishads, ISBN 978-1-58638-021-2, pages 298–299

- ↑ Mahadevan 1956, p. 56.

- ↑ Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-512435-4, page 12–14

- ↑ King & Ācārya 1995, p. 52.

- ↑ Ranade 1926, p. 12.

- ↑ Varghese 2008, p. 101.

- ↑ Jan Gonda (1970 through 1987), A History of Indian Literature, Volumes 1 to 7, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02676-5

- ↑ Teun Goudriaan and Sanjukta Gupta (1981), Hindu Tantric and Śākta Literature, A History of Indian Literature, Volume 2, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02091-6, pages 7–14

- ↑ Andrew Nicholson (2013), Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-14987-7, pages 2–5

- ↑ Karl Potter (1991), Presuppositions of India's Philosophies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0779-2

- 1 2 Greg Bailey (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (Editor: Oliver Leaman), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-17281-3, pages 437–439

- ↑ John Cort (1993), Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts (Editor: Wendy Doniger), State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1382-1, pages 185–204

- ↑ Gregory Bailey (2003), The Study of Hinduism (Editor: Arvind Sharma), The University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 978-1-57003-449-7, page 139

- ↑ Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5, pages 1–5, 12–21

- ↑ Nair, Shantha N. (2008). Echoes of Ancient Indian Wisdom: The Universal Hindu Vision and Its Edifice. Hindology Books. p. 266. ISBN 978-81-223-1020-7.

- 1 2 Cornelia Dimmitt (2015), Classical Hindu Mythology: A Reader in the Sanskrit Puranas, Temple University Press, ISBN 978-81-208-3972-4, page xii, 4

- ↑ Greg Bailey (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (Editor: Oliver Leaman), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-17281-3, page 503

- ↑ Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5, pages 12–13, 134–156, 203–210

- ↑ Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-20778-3, page xli

- ↑ Thompson, Richard L. (2007). The Cosmology of the Bhagavata Purana 'Mysteries of the Sacred Universe. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-208-1919-1.

- ↑ Gyula Wojtilla (2006), History of Kr̥ṣiśāstra, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-05306-8

- ↑ PK Acharya (1946), An Encyclopedia of Hindu Architecture, Oxford University Press, Also see Volumes 1 to 6

- ↑ Bruno Dagens (1995), MAYAMATA : An Indian Treatise on Housing Architecture and Iconography, ISBN 978-81-208-3525-2

- ↑ Karen Pechelis (2014), The Embodiment of Bhakti, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-535190-3

- ↑ The Sanskrit Drama, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Rachel Baumer and James Brandon (1993), Sanskrit Drama in Performance, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0772-3

- ↑ Mohan Khokar (1981), Traditions of Indian Classical Dance, Peter Owen Publishers, ISBN 978-0-7206-0574-7

- ↑ Hartmut Scharfe (2002), Education in Ancient India, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-12556-8

- ↑ John Brockington (1998), The Sanskrit Epics, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-10260-6

- ↑ Ludwik Sternbach (1974), Subhāṣita: Gnomic and Didactic Literature, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-01546-2

- ↑ Hartmut Scharfe, A history of Indian literature. Vol. 5, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-01722-8

- ↑ J Duncan M Derrett (1978), Dharmasastra and Juridical Literature: A history of Indian literature (Editor: Jan Gonda), Vol. 4, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-01519-5

- ↑ Claus Vogel, A history of Indian literature. Vol. 5, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-01722-8

- ↑ Kim Plofker (2009), Mathematics in India, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-12067-6

- ↑ David Pingree, A Census of the Exact Sciences in Sanskrit, Volumes 1 to 5, American Philosophical Society, ISBN 978-0-87169-213-9

- ↑ MS Valiathan, The Legacy of Caraka, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-81-250-2505-4

- ↑ Kenneth Zysk, Medicine in the Veda, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1401-1

- ↑ Emmie te Nijenhuis, Musicological literature (A History of Indian literature ; v. 6 : Scientific and technical literature ; Fasc. 1), Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-01831-9

- ↑ Lewis Rowell, Music and Musical Thought in Early India, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-73033-6

- ↑ Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5

- ↑ Karl Potter, The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volumes 1 through 27, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0309-4

- ↑ Edwin Gerow, A history of Indian literature. Vol. 5, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-01722-8

- ↑ JJ Meyer, Sexual Life in Ancient India, Vol 1 and 2, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-1-4826-1588-3

- ↑ Patrick Olivelle, King, Governance, and Law in Ancient India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-989182-5

- ↑ Teun Goudriaan, Hindu Tantric and Śākta Literature, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-02091-1

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch, Hindu Temple, Vol. 1 and 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0222-3

- ↑ Jan Gonda (1975), Vedic literature (Saṃhitās and Brāhmaṇas), Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-01603-5

Bibliography

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965). The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-0567-4.

- Deussen, Paul; Bedekar, V.M. (tr.); Palsule (tr.), G.B. (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1467-7.

- Collins, Randall (2000). The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00187-7.

- Mahadevan, T. M. P (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

- MacDonell, Arthur Anthony (2004). A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-2000-5.

- Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507045-3.

- Olivelle, Patrick (1998), Upaniṣads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283576-5

- Ranade, R. D. (1926), A constructive survey of Upanishadic philosophy, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan

- Varghese, Alexander P (2008), India : History, Religion, Vision And Contribution To The World, Volume 1, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 978-81-269-0903-2

Further reading

- R.C. Zaehner (1992), Hindu Scriptures, Penguin Random House, ISBN 978-0-679-41078-2

- Dominic Goodall, Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-20778-3

- Jessica Frazier (2014), The Bloomsbury Companion to Hindu studies, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1-4725-1151-5

External links

- Sacred-Texts: Hinduism

- Clay Sanskrit Library publishes Sanskrit literature with downloadable materials.

- Sanskrit Documents Collection: Documents in ITX format of Upanishads, Stotras etc.

- GRETIL: Göttingen Register of Electronic Texts in Indian Languages, a cumulative register of the numerous download sites for electronic texts in Indian languages.