Kumbh Mela

| Kumbh Mela कुम्भ मेला | |

|---|---|

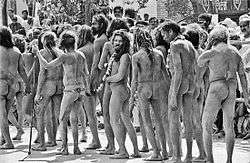

Pilgrims at the Haridwar Kumbh Mela in 2010 | |

| Status | active |

| Genre | Fair |

| Frequency | Every 12 years |

| Location(s) | Haridwar, Prayag (Allahabad), Nashik-Trimbak, and Ujjain |

| Country | India |

| Previous event | 2016 (Ujjain Simhastha) |

| Next event | 2022 (Haridwar Kumbh Mela) |

| Participants | Akharas, pilgrims and merchants |

Kumbh Mela or Kumbha Mela (/ˌkʊm ˈmeɪlə/ or /ˌkʊm məˈlɑː/) is a mass Hindu pilgrimage of faith in which Hindus gather to bathe in a sacred or holy river. Traditionally, four fairs are widely recognized as the Kumbh Melas: the Haridwar Kumbh Mela, the Allahabad Kumbh Mela, the Nashik-Trimbakeshwar Simhastha, and Ujjain Simhastha. These four fairs are held periodically at one of the following places by rotation: Haridwar, Allahabad (Prayaga), Nashik district (Nashik and Trimbak), and Ujjain. The main festival site is located on the banks of a river: the Ganges (Ganga) at Haridwar; the confluence (Sangam) of the Ganges and the Yamuna and the invisible Sarasvati at Allahabad; the Godavari at Nashik; and the Shipra at Ujjain. Bathing in these rivers is thought to cleanse a person of all sins.[1]

At any given place, the Kumbh Mela is held once in 12 years. There is a difference of around 3 years between the Kumbh Melas at Haridwar and Nashik; the fairs at Nashik and Ujjain are celebrated in the same year or one year apart. The exact date is determined according to a combination of zodiac positions of the Jupiter, the Sun and the Moon. At Nashik and Ujjain, the Mela may be held while a planet is in Leo (Simha in Hindu astrology); in this case, it is also known as Simhastha. At Haridwar and Allahabad, an Ardha ("Half") Kumbh Mela is held every sixth year; a Maha ("Great") Kumbh Mela occurs after 144 years.

The priests at other places have also claimed their local fairs to be Kumbh Melas. For example, the Mahamaham festival at Kumbakonam, held once in 12 years, is also portrayed as a Kumbh Mela.

The exact age of the festival is uncertain. According to medieval Hindu mythology, Lord Vishnu dropped drops of Amrita (the drink of immortality) at four places, while transporting it in a kumbha (pot). These four places are identified as the present-day sites of the Kumbh Mela. The name "Kumbh Mela" literally means "kumbha fair". It is known as "Kumbh" in Hindi (due to schwa deletion); in Sanskrit and some other Indian languages, it is more often known by its original name "Kumbha".[2]

The festival is one of the largest peaceful gatherings in the world, and considered as the "world's largest congregation of religious pilgrims".[3] There is no precise method of ascertaining the number of pilgrims, and the estimates of the number of pilgrims bathing on the most auspicious day may vary. An estimated 120 million people visited Maha Kumbh Mela in 2013 in Allahabad over a two-month period,[4][5] including over 30 million on a single day, on 10 February 2013 (the day of Mauni Amavasya).[6][7]

Mythological origin

According to medieval Hindu mythology, the origin of the festival can be found in the ancient legend of samudra manthan. The legend tells of a battle between the Devas and Asuras for amrita, the drink of immortality. During samudra manthan, or churning of the ocean, amrita was produced and placed in a kumbha (pot). To prevent the asuras (malevolent beings) from seizing the amrita, a divine carrier flew away with the pot. In one version of the legend, the carrier of the kumbha is the divine physician Dhanavantari, who stops at four places where the Kumbh Mela is celebrated. In other re-tellings, the carrier is Garuda, Indra or Mohini, who spills the amrita at four places.[8]

While several ancient texts, including the various Puranas, mention the samdura manthan legend, none of them mentions spilling of the amrita at four places.[8] Neither do these texts mention the Kumbh Mela. Therefore, multiple scholars, including R. B. Bhattacharya, D. P. Dubey and Kama Maclean believe that the samudra manthan legend has been applied to the Kumbh Mela relatively recently, in order to show scriptural authority for it.[9]

History

There are several references to river-side festivals in ancient Indian texts, but the exact age of the Kumbh Mela is uncertain. The Chinese traveler Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang) describes a ritual organized by Emperor Shiladitya (identified with Harsha) at the confluence of two rivers, in the kingdom of Po-lo-ye-kia (identified with Prayaga). He also mentions that many hundreds took a bath at the confluence, to wash away their sins.[10] According to some scholars, this is earliest surviving historical account of the Kumbh Mela, which took place in present-day Allahabad in 644 CE.[11][12][13] However, Australian researcher Kama Maclean notes that the Xuanzang reference is about an event that happened every 5 years (and not 12 years), and might have been a Buddhist celebration (since Harsha was a Buddhist emperor).[14]

A common conception, advocated by the akharas, is that Adi Shankara started the Kumbh Mela at Prayag in 8th century, to facilitate meeting of holy men from different regions. However, academics doubt the authenticity of this claim.[15]

The Kumbh Mela of Haridwar appears to be the original Kumbh Mela, since it is held according to the astrological sign "Kumbha" (Aquarius), and because there are several references to a 12-year cycle for it.[14] The earliest extant texts that contain the name "Kumbha Mela" are Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh (1695 CE) and Chahar Gulshan (1759 CE). Both these texts use the term "Kumbh Mela" to describe only Haridwar's fair, although they mention the similar fairs held in Allahabad and Nashik district.[16] The Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh lists the following melas: an annual mela and a Kumbh Mela every 12 years at Haridwar; a mela held at Trimbak when Jupiter enters Leo (that is, once in 12 years); and an annual mela held at Prayag in Magh.[17] The Magh Mela of Allahabad is probably the oldest among these, dating from the early centuries CE, and has been mentioned in several Puranas.[16] However, its association with the Kumbha myth and the 12-year old cycle is relatively recent, probably dating back to the mid-19th century. D. P. Dubey notes that none of the ancient Hindu texts mention the Allahabad fair as a "Kumbh Mela". Kama Maclean states that even early British records do not mention the name "Kumbh Mela" or the 12-year cycle for the Allahabad's fair. The first British reference to the Kumbh Mela in Allahabad occurs only in an 1868 report, which mentions the need for increased pilgrimage and sanitation controls at the "Coomb fair" to be held in January 1870. According to Maclean, the Prayagwal Brahmin priests of Allahabad adapted their annual Magh Mela to Kumbh legend, in order to increase the importance of their tirtha.[8]

The Kumbh Mela at Ujjain began in the 18th century, when the Maratha ruler Ranoji Shinde invited ascetics from Nashik to Ujjain for a local festival.[16] Like the priests at Allahabad, the pandits of Nashik and Ujjain, competing with other places for a sacred status, may have adopted the Kumbh tradition for their pre-existing melas.[8][14]

Until the East India Company rule, the Kumbh Melas were managed by the akharas (sects) of religious ascetics known as the sadhus. They collected taxes, and also carried out policing and judicial duties. The sadhus were heavily militarized, and also participated in trade. The Melas were a scene of sectarian politics, which sometimes turned violent.[18] The Chahar Gulshan states that the local sanyasis at Haridwar attacked the fakirs of Prayag who came to attend the Kumbh Mela there.[19] At the 1760 Kumbh Mela in Haridwar, a clash broke out between Shaivite Gosains and Vaishnavite Bairagis (ascetics), resulting in hundreds of deaths, with Vaishnavite forming most of the victims. A copper plate inscription of the Maratha Peshwa claims that 12,000 ascetics died in a clash between Shaivite sanyasis and Vaishnavite bairagis at the 1789 Nashik Kumbh Mela. The dispute started over the bathing order, which indicated status of the akharas.[20] At the 1796 Kumbh Mela in Haridwar, the Shaivites attacked and injured the Udasis for erecting a camp without their permission. In response, the Khalsa Sikhs accompanying the Udasis killed around 500 Gosains; the Sikhs lost around 20 men in the clash.[21][22] The clashes subsided after the Company administration severely limited the trader-warrior role of the sadhus, who were increasingly reduced to begging.[23]

Besides their religious significance, historically the Kumbh Melas were also major commercial events. Baptist missionary John Chamberlain, who visited the 1824 Ardh Kumbh Mela at Haridwar, stated that a large number of visitors came there for trade. He noted that the fair was attended by "multitudes of every religious order", including a large number of Sikhs.[24] According to an 1858 account of the Haridwar Kumbh Mela by the British civil servant Robert Montgomery Martin, the visitors at the fair included people from a number of races and religions. Besides priests, soldiers, and religious mendicants, the fair was attended by several merchants, including horse traders from Bukhara, Kabul, Turkistan, Arabia and Persia. Several Hindu rajas, Sikh rulers and Muslim Nawabs visited the fair. A few Christian missionaries also preached at the Mela.[25]

The Kumbh Melas played an important role in spread of the cholera outbreaks and pandemics. The British administrators made several attempts to improve the sanitary conditions at the Melas, but thousands of people died of cholera at these fairs until the mid-20th century.[26][27]

Several stampedes have occurred at the Kumbh Melas. After an 1820 stampede at Haridwar that killed 430 people, the Company government took extensive infrastructure projects, including construction of new ghats and road widening, to prevent further stampedes.[28] Since then Haridwar has experienced fewer deaths in stampedes: the next big stampede occurred in 1986, when 50 people were killed.[29] Allahabad has also experienced major stampedes, in 1840, 1906, 1954, 1986 and 2013. The deadliest of these was the 1954 stampede, which left 800 people dead.[30]

Places

Traditionally, the fairs at the following four sites are recognized as Kumbh Melas: Prayag (Allahabad), Haridwar, Trimbak-Nashik and Ujjain.[31][32] The Kumbh Mela in the Nashik district was originally held at Trimbak, but after a 1789 clash between Vaishnavites and Saivites over precedence of bathing, the Maratha Peshwa shifted the Vaishnavites' bathing place to Ramkund in Nashik city.[16] The Shaivites continue to regard Trimbak as the proper location.[33]

Priests at other places have also attempted to boost the status of their tirtha by adapting the Kumbh legends. The places whose festivals have been claimed as "Kumbh Mela" include Varanasi, Vrindavan, Tirumakudal Narsipur, Kumbhakonam (Mahamaham) and Rajim (Rajim Kumbh). Even Tibet has hosted a festival claimed to be a Kumbh Mela.[34][35]

Each site's celebration dates are calculated in advance according to a special combination of zodiacal positions of Bṛhaspati (Jupiter), the Sun and the Moon.

| Place | River | Zodiac[36] | Month | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haridwar | Ganga | Jupiter in Aquarius, Sun in Aries | Chaitra (March–April) | |

| Prayag (Allahabad) | Ganga and Yamuna | Jupiter in Aries, Sun and Moon in Capricorn; or Jupiter in Taurus and Sun in Capricorn | Magha (January–February) | "Magh Mela", called the "mini Kumbh Mela", is held annually |

| Trimbak-Nashik | Godavari | Jupiter in Leo; or Jupiter, Sun and Moon in Cancer on lunar conjunction (Amavasya) | Bhadrapada (August–September) | Also known as Simhastha / Sinhastha, when Leo is involved |

| Ujjain | Shipra | Jupiter in Leo, Sun in Aries; or Jupiter, Sun, and Moon in Libra on Kartik Amavasya | Vaisakha (April–May) | Also known as Simhastha / Sinhastha, when Leo is involved |

Dates

The Kumbh Mela occurrences follow the Hindu calendar, as follows:[32]

- The Kumbh Mela (sometimes specifically called Purna Kumbh or "full Kumbha"), occurs every 12 years at a given site.

- Ardh Kumbh ("Half Kumbh") Mela occurs between the two Purna Kumbha Melas at Prayag and Haridwar.

- The Maha Kumbh occurs after 12 Purna Kumbh Melas i.e. every 144 years.

The Kumbh Mela at Prayag is celebrated after approximately 3 years of Kumbh Mela at Haridwar. There is a difference of around 3 years between the Kumbh Festivals at Prayag and Nashik. Kumbh at Nashik and Ujjain are celebrated in the same year or one year apart.[36]

| Year | Prayag (Allahabad) | Haridwar | Trimbak (Nashik) | Ujjain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Kumbh Mela | Kumbh Mela | ||

| 1983 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | |||

| 1986 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 1989 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 1992 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | Kumbh Mela | Kumbh Mela | |

| 1995 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | |||

| 1998 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2001 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2003 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2004 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | Kumbh Mela | ||

| 2007 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2010 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2013 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2015 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2016 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | Kumbh Mela | ||

| 2019 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2021/2022 | Kumbh Mela |

Attendance

According to The Imperial Gazetteer of India, an outbreak of cholera occurred at the 1892 Mela at Haridwar leading to the rapid improvement of arrangements by the authorities and to the formation of Haridwar Improvement Society. In 1903 about 400,000 people are recorded as attending the fair.[37] During the 1954 Kumbh Mela stampede at Prayag, around 500 people were killed, and scores were injured. Ten million people gathered at Haridwar for the Kumbh on 14 April 1998.[38]

In 2001, more than 40 million gathered on the busiest of its 55 days.[39]

According to the Mela Administration's estimates, around 70 million people participated in the 45-day Ardha Kumbh Mela at Prayag in 2007.[40]

The 2001 Kumbh Mela at Allahabad (Prayag) was estimated by the authorities to have attracted between 30 and 70 million people.[41][42][43] The estimated attendance for the 2013 Allahabad Kumbh Mela was 120 million.[7]

The ritual

One of the major events of Kumbh Mela is the Peshwai Procession, which marks the arrival of the members of an akhara or sect of sadhus at the Kumbh Mela.[44] The major event of the festival is ritual bathing at the banks of the river in whichever town Kumbh Mela being held:Ganga in Haridwar, Godavari in Nasik, Kshipra in Ujjain and Sangam (confluence of Ganga, Yamuna and mythical Saraswati) in Allahabad (Prayag). Nasik has registered maximum visitors to 75 million. Other activities include religious discussions, devotional singing, mass feeding of holy men and women and the poor, and religious assemblies where doctrines are debated and standardised. Kumbh Mela is the most sacred of all the pilgrimages. Thousands of holy men and women attend, and the auspiciousness of the festival is in part attributable to this. The sadhus are seen clad in saffron sheets with Vibhuti ashes dabbed on their skin as per the requirements of ancient traditions. Some, called naga sanyasis, may not wear any clothes even in severe winter. The right to be naga, or naked, is considered a sign of separation from the material world.[1]

After visiting the Kumbh Mela of 1895, Mark Twain wrote:

| “ | It is wonderful, the power of a faith like that, that can make multitudes upon multitudes of the old and weak and the young and frail enter without hesitation or complaint upon such incredible journeys and endure the resultant miseries without repining. It is done in love, or it is done in fear; I do not know which it is. No matter what the impulse is, the act born of it is beyond imagination, marvelous to our kind of people, the cold whites.[45] | ” |

The order of entering the water is fixed, with the Juna, the Niranjani and Mahanirvani akharas preceding.[46]

Darshan

Darshan, or respectful visual exchange, is an important part of the Kumbh Mela. People make the pilgrimage to the Kumbh Mela specifically to see and experience both the religious and secular aspects of the event. Two major groups that participate in the Kumbh Mela include the Sadhus (Hindu holy men) and pilgrims. Through their continual yogic practices the Sadhus articulate the transitory aspect of life. Sadhus travel to the Kumbh Mela to make themselves available to much of the Hindu public. This allows members of the Hindu public to interact with the Sadhus and to take "darshan." They are able to "seek instruction or advice in their spiritual lives." Darshan focuses on the visual exchange, where there is interaction with a religious deity and the worshiper is able to visually "'drink' divine power." The Kumbh Mela is arranged in camps that give Hindu worshipers access to the Sadhus. The darshan is important to the experience of the Kumbh Mela and because of this worshipers must be careful so as to not displease religious deities. Seeing of the Sandus is carefully managed and worshipers often leave tokens at their feet.[1]

Kumbh Mela in media

Kumbh Mela has received extensive media coverage, with several documentaries and films based on it.

Kumbh Mela has been theme for many a documentaries, including Kings with Straw Mats (1998) directed by Ira Cohen, Kumbh Mela: The Greatest Show on Earth (2001) directed by Graham Day,[47] Short Cut to Nirvana: Kumbh Mela (2004) directed by Nick Day and produced by "Maurizio Benazzo",[48] Kumbh Mela: Songs of the River (2004) by Nadeem Uddin,[49] Invocation, Kumbh Mela (2008), Kumbh Mela: Walking with the Nagas (2011), Amrit: Nectar of Immortality (2012) directed by Jonas Scheu and Philipp Eyer,[50] Inside the Mahakumbh (2013) by the National Geographic Channel and Kumbh Mela 2013: living with Mahatiagi (2013) by the Ukrainian Religious Studies Project Ahamot.[51]

Indian and foreign news media have covered the Kumbh Mela regularly. On 18 April 2010, a popular American morning show CBS News Sunday Morning extensively covered Haridwar's Kumbh Mela, calling it "The Largest Pilgrimage on Earth". On 28 April 2010, BBC reported an audio and a video report on Kumbh Mela, titled "Kumbh Mela 'greatest show on earth."

Young siblings getting separated at the Kumbh Mela were once a recurring theme in Hindi movies.[52] Amrita Kumbher Sandhane, a 1982 Bengali feature film directed by Dilip Roy, also documents the Kumbh Mela. On 30 September 2010, the Kumbh Mela featured in the second episode of the Sky One TV series "An Idiot Abroad" with Karl Pilkington visiting the festival.

See also

- Similar festivals: Mahamaham and Pushkaram

- List of largest gatherings in history

- Kumbathon

References

- 1 2 3 McLean, Kama. "Seeing, Being Seen, and Not Being Seen: Pilgrimage, Tourism, and Layers of Looking at the Kumbh Mela." (2009): 319-41. Ebscohost. Web. 28 Sept. 2014..

- ↑ "Kumbh Mela 2015-16: Nashik City" (PDF). Police Commissionerate, Nasik City. 2014.

- ↑ The Maha Kumbh Mela 2001 indianembassy.org

- ↑ "Record 120 million take dip as Maha Kumbh fest ends". Khaleej Times. 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Photos: Kumbh Mela, world's biggest religious festival". CNN. 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "Over 3 crore take holy dip in Sangam on Mauni Amavasya". IBNLive. 10 February 2013.

- 1 2 Rashid, Omar (11 February 2013). "Over three crore devotees take the dip at Sangam". The Hindu. Chennai.

- 1 2 3 4 Kama MacLean (August 2003). "Making the Colonial State Work for You: The Modern Beginnings of the Ancient Kumbh Mela in Allahabad". The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (3): 873–905. doi:10.2307/3591863. JSTOR 3591863.

- ↑ Maclean 2008, pp. 88-89.

- ↑ Buddhist Records of the Western World, Book V by Xuan Zang

- ↑ Dilip Kumar Roy; Indira Devi (1955). Kumbha: India's ageless festival. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. xxii.

- ↑ Mark Tully (1992). No Full Stops in India. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-0-14-192775-6.

- ↑ Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. pp. 677–. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5.

- 1 2 3 Vikram Doctor (2013-02-10). "Kumbh mela dates back to mid-19th century, shows research". Economic Times.

- ↑ Maclean 2008, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 4 James G. Lochtefeld (2008). "The Kumbh Mela Festival Processions". In Knut A. Jacobsen. South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge. pp. 32–41.

- ↑ Jadunath Sarkar (1901). India of Aurangzib. Kinnera. pp. 27–124.

- ↑ William R. Pinch (1996). "Soldier Monks and Militant Sadhus". In David Ludden. Contesting the Nation. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 141–156. ISBN 9780812215854.

- ↑ Jadunath Sarkar (1901). India of Aurangzib. Kinnera. p. 124.

- ↑ James Lochtefeld (2009). Gods Gateway: Identity and Meaning in a Hindu Pilgrimage Place. Oxford University Press. pp. 252–253. ISBN 9780199741588.

- ↑ Thomas Hardwicke (1801). Narrative of a Journey to Sirinagur. pp. 314–319.

- ↑ Hari Ram Gupta (2001). History of the Sikhs: The Sikh commonwealth or Rise and fall of Sikh misls (Volume IV). Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 175. ISBN 978-81-215-0165-1.

- ↑ Maclean 2008, pp. 57-58.

- ↑ John Chamberlain; William Yates (1826). Memoirs of Mr. John Chamberlain, late missionary in India. Baptist Mission Press. pp. 346–348.

- ↑ Robert Montgomery Martin (1858). The Indian Empire. 3. The London Printing and Publishing Company. pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Biswamoy Pati; Mark Harrison (2008). The Social History of Health and Medicine in Colonial India. Routledge. pp. 68–71. ISBN 978-1-134-04259-3.

- ↑ R. Dasgupta. "Time Trends of Cholera in India : An Overview" (PDF). INFLIBNET. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ↑ Maclean 2008, p. 61.

- ↑ "Five die in stampede at Hindu bathing festival". BBC. 14 April 2010.

- ↑ "Maha Kumbh Mela (1954): 800 dead". rediff.com. 4 March 2010.

- ↑ J. S. Mishra (2004). Mahakumbh, the Greatest Show on Earth. Har-Anand Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-241-0993-9.

- 1 2 J. C. Rodda; Lucio Ubertini; Symposium on the Basis of Civilization--Water Science? (2004). The Basis of Civilization--water Science?. International Association of Hydrological Science. pp. 165–. ISBN 978-1-901502-57-2.

- ↑ Vaishali Balajiwale (13 July 2015). "Project Trimbak, not Nashik, as the place for Kumbh: Shaiva akhadas". DNA.

- ↑ "Kumbh Mela concludes at T. Narsipur". The Hindu. 7 February 2004.

- ↑ Maclean 2008, p. 102.

- 1 2 Mela Adhikari Kumbh Mela 2013. "Official Website of Kumbh Mela 2013 Allahabad Uttar Pradesh India". Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ↑ Haridwar The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909, v. 13, p. 52.

- ↑ What Is Hinduism?: Modern Adventures into a Profound Global Faith. Himalayan Academy Publications. pp. 242–243. ISBN 978-1-934145-27-2.

- ↑ "India's Hindu Kumbh Mela festival begins in Allahabad". BBC News.

- ↑ "Ardha Kumbh – 2007: The Ganges River". Mela Administration. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ↑ Kumbh Mela pictured from space – probably the largest human gathering in history BBC News, 26 January 2001.

- ↑ Kumbh Mela: the largest pilgrimage – Pictures: Kumbh Mela by Karoki Lewis The Times, 22 March 2008. Behind paywall.

- ↑ Kumbh Mela, New Scientist, 25 January 2001

- ↑ Sadhus astride elephants, horses at Maha Kumbh

- ↑ Mark Twain, "Following the Equator: A journey around the world"

- ↑ Nandita Sengupta (13 February 2010). "Naga sadhus steal the show at Kumbh", TNN

- ↑ Kumbh Mela: The Greatest Show on Earth at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Short Cut to Nirvana - A Documentary about the Kumbh Mela Spiritual Festival". Mela Films.

- ↑ Kumbh Mela: Songs of the River at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Amrit:Nectar of Immortality". Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ↑ Kumbh Mela 2013: Living with Mahatiagi

- ↑ "Why twins no longer get separated at Kumbh Mela". rediff.com. 15 January 2010.

Bibliography

- Maclean, Kama (28 August 2008). Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765-1954. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-533894-2.

- Harvard University, South Asia Institute (2015) Kumbh Mela: Mapping the Ephemeral Megacity New Delhi: Niyogi Books. ISBN 9789385285073

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kumbh Mela. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Official websites of Kumbh Mela