MAX (gene)

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

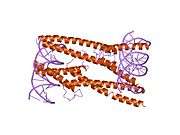

Protein max also known as myc-associated factor X is a protein that in humans is encoded by the MAX gene.[3][4]

Function

The protein max is a member of the basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper (bHLHZ) family of transcription factors. It is able to form homodimers and heterodimers with other family members, which include Mad, Mxl1 and Myc. Myc is an oncoprotein implicated in cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. The homodimers and heterodimers compete for a common DNA target site (the E-box) and rearrangement among these dimer forms provides a complex system of transcriptional regulation. Multiple alternatively spliced transcript variants have been described for this gene but the full-length nature for some of them is unknown.[4]

Max binds to itself and to other transcription factors through its leucine zipper to form homo- and hetero-dimers respectively. Max itself lacks a transactivation domain so that Max homodimers have a repressive function. In contrast, Myc contains a transactivation domain but cannot homodimerize. However Myc can heterodimerize with Max to form heterodimers that can both bind DNA and transactivate. The transcriptionally active Max/Myc dimer promotes cell proliferation as well as apoptosis.[5]

Interactions

MAX (gene) has been shown to interact with:

- Myc,[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

- MNT,[15]

- MSH2,[10]

- MXD1,[12][14][16][19]

- MXI1,[13][15][17][20]

- MYCL1,[11][17]

- N-Myc,[11][17]

- SPAG9,[12]

- TEAD1,[21] and

- Transformation/transcription domain-associated protein.[7][8]

Clinical relevance

This gene has been shown mutated in cases of hereditary pheochromocytoma.[22] More recently the MAX gene has been shown to be mutated also in small cell lung cancer (SCLC). This is mutually exclusive with alterations at MYC and BRG1, the latter coding for an ATPase of the SWI/SNF complex. It was demonstrated that BRG1 regulates the expression of MAX through direct recruitment to the MAX promoter, and that depletion of BRG1 strongly hinders cell growth, specifically in MAX-deficient cells, heralding a synthetic lethal interaction. Furthermore, MAX required BRG1 to activate neuroendocrine transcriptional programs and to up-regulate MYC-targets, such as glycolytic-related genes.[23]

References

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ Wagner AJ, Le Beau MM, Diaz MO, Hay N (May 1992). "Expression, regulation, and chromosomal localization of the Max gene". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 89 (7): 3111–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.7.3111. PMC 48814

. PMID 1557420.

. PMID 1557420. - 1 2 "Entrez Gene: MAX MYC associated factor X".

- ↑ Amati B, Land H (February 1994). "Myc-Max-Mad: a transcription factor network controlling cell cycle progression, differentiation and death". Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 4 (1): 102–8. doi:10.1016/0959-437X(94)90098-1. PMID 8193530.

- ↑ Ewing RM, Chu P, Elisma F, Li H, Taylor P, Climie S, McBroom-Cerajewski L, Robinson MD, O'Connor L, Li M, Taylor R, Dharsee M, Ho Y, Heilbut A, Moore L, Zhang S, Ornatsky O, Bukhman YV, Ethier M, Sheng Y, Vasilescu J, Abu-Farha M, Lambert JP, Duewel HS, Stewart II, Kuehl B, Hogue K, Colwill K, Gladwish K, Muskat B, Kinach R, Adams SL, Moran MF, Morin GB, Topaloglou T, Figeys D (2007). "Large-scale mapping of human protein-protein interactions by mass spectrometry". Mol. Syst. Biol. 3: 89. doi:10.1038/msb4100134. PMC 1847948

. PMID 17353931.

. PMID 17353931. - 1 2 McMahon SB, Wood MA, Cole MD (January 2000). "The essential cofactor TRRAP recruits the histone acetyltransferase hGCN5 to c-Myc". Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 (2): 556–62. doi:10.1128/MCB.20.2.556-562.2000. PMC 85131

. PMID 10611234.

. PMID 10611234. - 1 2 McMahon SB, Van Buskirk HA, Dugan KA, Copeland TD, Cole MD (August 1998). "The novel ATM-related protein TRRAP is an essential cofactor for the c-Myc and E2F oncoproteins". Cell. 94 (3): 363–74. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81479-8. PMID 9708738.

- ↑ Cheng SW, Davies KP, Yung E, Beltran RJ, Yu J, Kalpana GV (May 1999). "c-MYC interacts with INI1/hSNF5 and requires the SWI/SNF complex for transactivation function". Nat. Genet. 22 (1): 102–5. doi:10.1038/8811. PMID 10319872.

- 1 2 Mac Partlin M, Homer E, Robinson H, McCormick CJ, Crouch DH, Durant ST, Matheson EC, Hall AG, Gillespie DA, Brown R (February 2003). "Interactions of the DNA mismatch repair proteins MLH1 and MSH2 with c-MYC and MAX". Oncogene. 22 (6): 819–25. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206252. PMID 12584560.

- 1 2 3 Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN (Mar 1991). "Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc". Science. UNITED STATES. 251 (4998): 1211–7. doi:10.1126/science.2006410. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 2006410.

- 1 2 3 Lee CM, Onésime D, Reddy CD, Dhanasekaran N, Reddy EP (October 2002). "JLP: A scaffolding protein that tethers JNK/p38MAPK signaling modules and transcription factors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (22): 14189–94. doi:10.1073/pnas.232310199. PMC 137859

. PMID 12391307.

. PMID 12391307. - 1 2 Billin AN, Eilers AL, Queva C, Ayer DE (December 1999). "Mlx, a novel Max-like BHLHZip protein that interacts with the Max network of transcription factors". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (51): 36344–50. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.51.36344. PMID 10593926.

- 1 2 Gupta K, Anand G, Yin X, Grove L, Prochownik EV (March 1998). "Mmip1: a novel leucine zipper protein that reverses the suppressive effects of Mad family members on c-myc". Oncogene. 16 (9): 1149–59. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201634. PMID 9528857.

- 1 2 3 Meroni G, Reymond A, Alcalay M, Borsani G, Tanigami A, Tonlorenzi R, Lo Nigro C, Messali S, Zollo M, Ledbetter DH, Brent R, Ballabio A, Carrozzo R (May 1997). "Rox, a novel bHLHZip protein expressed in quiescent cells that heterodimerizes with Max, binds a non-canonical E box and acts as a transcriptional repressor". EMBO J. 16 (10): 2892–906. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.10.2892. PMC 1169897

. PMID 9184233.

. PMID 9184233. - 1 2 Nair SK, Burley SK (January 2003). "X-ray structures of Myc-Max and Mad-Max recognizing DNA. Molecular bases of regulation by proto-oncogenic transcription factors". Cell. 112 (2): 193–205. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01284-9. PMID 12553908.

- 1 2 3 4 FitzGerald MJ, Arsura M, Bellas RE, Yang W, Wu M, Chin L, Mann KK, DePinho RA, Sonenshein GE (April 1999). "Differential effects of the widely expressed dMax splice variant of Max on E-box vs initiator element-mediated regulation by c-Myc". Oncogene. 18 (15): 2489–98. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202611. PMID 10229200.

- ↑ Meroni G, Cairo S, Merla G, Messali S, Brent R, Ballabio A, Reymond A (July 2000). "Mlx, a new Max-like bHLHZip family member: the center stage of a novel transcription factors regulatory pathway?". Oncogene. 19 (29): 3266–77. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203634. PMID 10918583.

- ↑ Ayer DE, Kretzner L, Eisenman RN (January 1993). "Mad: a heterodimeric partner for Max that antagonizes Myc transcriptional activity". Cell. 72 (2): 211–22. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90661-9. PMID 8425218.

- ↑ Rual JF, Venkatesan K, Hao T, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Dricot A, Li N, Berriz GF, Gibbons FD, Dreze M, Ayivi-Guedehoussou N, Klitgord N, Simon C, Boxem M, Milstein S, Rosenberg J, Goldberg DS, Zhang LV, Wong SL, Franklin G, Li S, Albala JS, Lim J, Fraughton C, Llamosas E, Cevik S, Bex C, Lamesch P, Sikorski RS, Vandenhaute J, Zoghbi HY, Smolyar A, Bosak S, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stamm L, Cusick ME, Hill DE, Roth FP, Vidal M (October 2005). "Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network". Nature. 437 (7062): 1173–8. doi:10.1038/nature04209. PMID 16189514.

- ↑ Gupta MP, Amin CS, Gupta M, Hay N, Zak R (July 1997). "Transcription enhancer factor 1 interacts with a basic helix-loop-helix zipper protein, Max, for positive regulation of cardiac alpha-myosin heavy-chain gene expression". Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 (7): 3924–36. doi:10.1128/mcb.17.7.3924. PMC 232245

. PMID 9199327.

. PMID 9199327. - ↑ Comino-Méndez I, Gracia-Aznárez FJ, Schiavi F, Landa I, Leandro-García LJ, Letón R, Honrado E, Ramos-Medina R, Caronia D, Pita G, Gómez-Graña A, de Cubas AA, Inglada-Pérez L, Maliszewska A, Taschin E, Bobisse S, Pica G, Loli P, Hernández-Lavado R, Díaz JA, Gómez-Morales M, González-Neira A, Roncador G, Rodríguez-Antona C, Benítez J, Mannelli M, Opocher G, Robledo M, Cascón A (July 2011). "Exome sequencing identifies MAX mutations as a cause of hereditary pheochromocytoma". Nat. Genet. 43 (7): 663–7. doi:10.1038/ng.861. PMID 21685915.

- ↑ Romero OA, Torres-Diz M, Pros E, Savola S, Gomez A, Moran S, Saez C, Iwakawa R, Villanueva A, Montuenga LM, Kohno T, Yokota J, Sanchez-Cespedes M (Dec 2013). "MAX inactivation in small-cell lung cancer disrupts the MYC-SWI/SNF programs and is synthetic lethal with BRG1.". Cancer Discov. 4: 292–303. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0799. PMID 24362264.

Further reading

- Grandori C, Cowley SM, James LP, Eisenman RN (2001). "The Myc/Max/Mad network and the transcriptional control of cell behavior.". Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16: 653–99. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.653. PMID 11031250.

- Lüscher B (2001). "Function and regulation of the transcription factors of the Myc/Max/Mad network.". Gene. 277 (1-2): 1–14. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00697-7. PMID 11602341.

- Wechsler DS, Dang CV (1992). "Opposite orientations of DNA bending by c-Myc and Max.". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 (16): 7635–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.16.7635. PMC 49765

. PMID 1323849.

. PMID 1323849. - Mäkelä TP, Koskinen PJ, Västrik I, Alitalo K (1992). "Alternative forms of Max as enhancers or suppressors of Myc-ras cotransformation.". Science. 256 (5055): 373–7. doi:10.1126/science.256.5055.373. PMID 1566084.

- Gilladoga AD, Edelhoff S, Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN, Disteche CM (1992). "Mapping of MAX to human chromosome 14 and mouse chromosome 12 by in situ hybridization.". Oncogene. 7 (6): 1249–51. PMID 1594250.

- Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN (1991). "Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc.". Science. 251 (4998): 1211–7. doi:10.1126/science.2006410. PMID 2006410.

- Zervos AS, Faccio L, Gatto JP, Kyriakis JM, Brent R (1995). "Mxi2, a mitogen-activated protein kinase that recognizes and phosphorylates Max protein.". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (23): 10531–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.23.10531. PMC 40645

. PMID 7479834.

. PMID 7479834. - Bousset K, Henriksson M, Lüscher-Firzlaff JM, Litchfield DW, Lüscher B (1993). "Identification of casein kinase II phosphorylation sites in Max: effects on DNA-binding kinetics of Max homo- and Myc/Max heterodimers.". Oncogene. 8 (12): 3211–20. PMID 8247525.

- Ayer DE, Kretzner L, Eisenman RN (1993). "Mad: a heterodimeric partner for Max that antagonizes Myc transcriptional activity.". Cell. 72 (2): 211–22. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90661-9. PMID 8425218.

- Västrik I, Koskinen PJ, Alitalo R, Mäkelä TP (1993). "Alternative mRNA forms and open reading frames of the max gene.". Oncogene. 8 (2): 503–7. PMID 8426752.

- Ferré-D'Amaré AR, Prendergast GC, Ziff EB, Burley SK (1993). "Recognition by Max of its cognate DNA through a dimeric b/HLH/Z domain.". Nature. 363 (6424): 38–45. doi:10.1038/363038a0. PMID 8479534.

- Hurlin PJ, Quéva C, Koskinen PJ, Steingrímsson E, Ayer DE, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Eisenman RN (1996). "Mad3 and Mad4: novel Max-interacting transcriptional repressors that suppress c-myc dependent transformation and are expressed during neural and epidermal differentiation.". EMBO J. 14 (22): 5646–59. PMC 394680

. PMID 8521822.

. PMID 8521822. - Grandori C, Mac J, Siëbelt F, Ayer DE, Eisenman RN (1996). "Myc-Max heterodimers activate a DEAD box gene and interact with multiple E box-related sites in vivo.". EMBO J. 15 (16): 4344–57. PMC 452159

. PMID 8861962.

. PMID 8861962. - Brownlie P, Ceska T, Lamers M, Romier C, Stier G, Teo H, Suck D (1997). "The crystal structure of an intact human Max-DNA complex: new insights into mechanisms of transcriptional control.". Structure. 5 (4): 509–20. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(97)00207-4. PMID 9115440.

- Meroni G, Reymond A, Alcalay M, Borsani G, Tanigami A, Tonlorenzi R, Lo Nigro C, Messali S, Zollo M, Ledbetter DH, Brent R, Ballabio A, Carrozzo R (1997). "Rox, a novel bHLHZip protein expressed in quiescent cells that heterodimerizes with Max, binds a non-canonical E box and acts as a transcriptional repressor.". EMBO J. 16 (10): 2892–906. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.10.2892. PMC 1169897

. PMID 9184233.

. PMID 9184233. - Gupta MP, Amin CS, Gupta M, Hay N, Zak R (1997). "Transcription enhancer factor 1 interacts with a basic helix-loop-helix zipper protein, Max, for positive regulation of cardiac alpha-myosin heavy-chain gene expression.". Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 (7): 3924–36. doi:10.1128/mcb.17.7.3924. PMC 232245

. PMID 9199327.

. PMID 9199327. - Gupta K, Anand G, Yin X, Grove L, Prochownik EV (1998). "Mmip1: a novel leucine zipper protein that reverses the suppressive effects of Mad family members on c-myc.". Oncogene. 16 (9): 1149–59. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201634. PMID 9528857.

- Lavigne P, Crump MP, Gagné SM, Hodges RS, Kay CM, Sykes BD (1998). "Insights into the mechanism of heterodimerization from the 1H-NMR solution structure of the c-Myc-Max heterodimeric leucine zipper.". J. Mol. Biol. 281 (1): 165–81. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1998.1914. PMID 9680483.

- FitzGerald MJ, Arsura M, Bellas RE, Yang W, Wu M, Chin L, Mann KK, DePinho RA, Sonenshein GE (1999). "Differential effects of the widely expressed dMax splice variant of Max on E-box vs initiator element-mediated regulation by c-Myc.". Oncogene. 18 (15): 2489–98. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202611. PMID 10229200.

External links

- MAX protein, human at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- FactorBook Max

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.