Mokume-gane

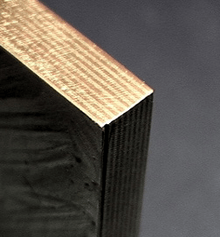

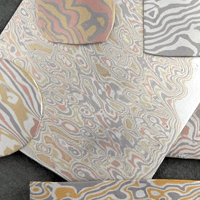

Mokume-gane (木目金 Mokumegane) is a Japanese metalworking procedure which produces a mixed-metal laminate with distinctive layered patterns. Mokume gane translates closely to "wood grain metal" or "wood eye metal", describing the way the metal takes on the appearance of natural wood grain.[1]

Mokume-gane has been used to create many artistic objects. Though the technique was first created to decorate swords, the art survives today mostly in the form of jewelry and hollowware.[2]

Mokume-gane is a product made by fusing several layers of different coloured precious metals together to form a sandwich of alloys called a billet. The billet is then manipulated in such a way that a pattern resembling wood grain emerges over the surface.

There are many ways of working the mokume metal to create different patterns. Once the metal has been rolled in to sheet metal or bar, several techniques are used to produce a variety of effects. [3]

History

First made in 17th-century Japan, mokume-gane was used only for swords. As the traditional samurai sword stopped serving as a weapon and became largely a status symbol, a demand arose for elaborate decorative handles and sheaths.[4]

To meet this demand, Denbei Shoami (1651–1728), a master metalworker from Akita prefecture, first came up with the process for creating mokume-gane. He initially called his product guri bori for its simplest form's resemblance to guri, a type of carved lacquerwork with alternating layers of red and black. Other historical names for it were kasumi-uchi (cloud metal), itame-gane (wood-grain metal), and yosefuki.[5]

The traditional components were relatively soft metallic elements and alloys (gold, copper, silver, shakudō, shibuichi, and kuromido) which would form liquid phase diffusion bonds with one another without completely melting. This was useful in the traditional techniques of fusing and soldering the layers together.[4]

Over time, the practice of making mokume-gane faded. The katana industry dried up in the late 1800s when the traditional caste system dissolved and people were no longer able to carry their swords in public. The few metalsmiths who practiced in mokume transferred their skills to create other objects.[2]

Tiffany & Co.'s silver division under the direction of Edward C. Moore began to experiment with mokume-gane techniques around 1877 and at the Paris exposition of 1878 Tiffany's in its grand prize-winning display of Moore's "Japanesque" silver wares included a magnificent "Conglomerate Vase" with asymmetrical panels of mokume. (The Conglomerate Vase which has been widely acclaimed as the most important work of nineteenth-century American silver was sold at Sotheby's on January 20, 1998 for $585,500.) Moore and Tiffany's silver smiths continued to develop its popular mokume techniques in preparation for the Paris exposition of 1889 where it displayed a vast array of Japanesque silver using ever more complex alloys of shakado, sedo and shibuci along with gold and silver to make laminates of up to twenty-four layers. Tiffany's display again won the grand prize for silver wares, and the company continued to produce its Japanesque silver with mokume up into the twentieth century.[6]

By the twentieth century, mokume-gane was almost entirely unknown. Japan’s movement away from traditional craftwork, paired with the great difficulty of mastering the mokume-gane art had brought mokume artisans to the brink of extinction. It reached a point where only scholars and collectors of metalwork were aware of the technique.[4] It was not until the 1970s, when Eugene Michael Pijanowski and Hiroko Sato Pijanowski brought mokume works to the United States, that the artform re-emerged in the public eye. Today, jewelry, flatware, hollowware, spinning tops and other artistic objects are made using this material.[2]

Modern processes are highly controlled and include a compressive force on the billet. This has allowed the technique to include many nontraditional components such as titanium, platinum, iron, bronze, brass, nickel silver, and various colors of karat gold including yellow, white, sage, and rose hues as well as sterling silver.[4]

Techniques

Fusing (traditional)

Metal sheets were stacked and carefully heated; the solid billet of simple stripes could be forged and carved to increase the pattern's complexity. Successful lamination using the traditional process requires a highly skilled smith with a great deal of experience. Bonding in the traditional process is achieved when some or all of the alloys in the stack are heated to the point of becoming partially molten (above solidus) this liquid alloy is what fuses the layers together. Careful heat control and skillful forging are required for this process.[4]

Soldering (brazing)

The sheets were soldered using silver solder or some other brazing alloy. This technique joined the metals, but is difficult to perfect, particularly on larger sheets. Flux inclusions could be trapped or bubbles could form. Commonly, imperfections need to be cut out, and the metal re-soldered.

Solid-state bonding (modern)

The modernized process typically uses a controlled atmosphere in a temperature-controlled furnace. Mechanical aids such as a hydraulic press or torque plates (bolted clamps) are also typically used to apply compressive force on the billet during lamination. These provide for the implementation of lower temperature solid-state diffusion between the interleaved layers, thus allowing the inclusion of non-traditional materials.[4]

Development of the mokume pattern

After the fusion of layers, the surface of the billet is cut with chisel to expose lower layers, then flattened. This cutting and flattening process will be repeated over and over again to develop intricate patterns.[5]

Coloring

To increase the contrast between the laminate layers many mokume-gane items are colored by the application of a patina (a controlled corrosion layer) to accentuate or even totally change the colors of the metal's surface.

Rokushō

One example of a traditional Japanese patination for mokume-gane is the use of rokushō. Rokushō is a complex copper verdigris compound produced specifically for use as a patina.

To color the shakudō and gold, the piece is immersed in boiling rokushō until it reaches the desired color. Rokushō colors shakudō a black-purple. The more gold is in the alloy, the more purple it turns.

Rokushō is produced in small batches in a traditional process and is somewhat difficult to acquire outside Japan. There are some proposed substitute formulae (see rokushō article.)

Traditionally a paste of ground daikon radish is also used to prepare the work for the patina. The paste is applied immediately before the piece is boiled in the rokushō to protect the surface against tarnish and uneven coloring.[5]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mokume-gane. |

References

- ↑ Midgett, Steve (2000). Mokume Gane A comprehensive study. earthshine press. ISBN 0-9651650-7-8.

- 1 2 3 "About Mokume Gane". Andrew NYCE Designs. 2002. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- ↑ "Blog Article Mokume Gane". Larsen Jewellery. 2016. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Binnion, J. E. & Chaix, B. (2002). "Old Process, New Technology: Modern Mokume Gane" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- 1 2 3 Pijanowski, H.S. & Pijanowski, G.M. (2001). "Wood Grained Metal: Mokume-Gane". Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ Loring, John (2001). Magnificent Tiffany Silver. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-4273-9.

- ↑ "Mokume Gane - Larsen Jewellery". Larsen Jewellery. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

External links

![]() Media related to Mokume-gane at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mokume-gane at Wikimedia Commons