History of women in Puerto Rico

| ||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1,940,618 (females)[1]) | ||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||

| Spanish and English | ||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Protestant, Roman Catholic | ||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||

| Europeans, Africans, Taínos, Criollos, Mestizos, Mulattos | ||||||||||

The history of women in Puerto Rico traces back its roots to the Taíno, the inhabitants of the island before the arrival of Spaniards. During the Spanish colonization the cultures and customs of the Taíno, Spanish, African and women from non-Hispanic countries blended into what became the culture and customs of Puerto Rico. Many women in Puerto Rico were Spanish subjects and were already active participants in the labor movement and in the agricultural economy of the island.[2]

After Puerto Rico was ceded to the United States in 1898 as a result of the Spanish–American War, women once again played an integral role in Puerto Rican society by contributing to the establishment of the state university of Puerto Rico, women's suffrage, women's rights, civil rights, and to the military of the United States.

During the period of industrialization of the 1950s, women in Puerto Rico took jobs in the needle industry, working as seamstresses in garment factories.[2] Many Puerto Rican families also migrated to the United States in the 1950s, which included women. Currently, women in Puerto Rico have become active in the political and social landscape in the continental United States in addition to their own homeland, with many of them involved in fields that were once limited to the male population, as well as gaining influential roles as leaders in their fields.

Pre-Columbian era

Puerto Rico was inhabited by the Taíno, one of the Arawak peoples of South America, before the arrival of Spaniards. Taíno women cooked, tended to the needs of the family, their farms and harvested crops. According to "Ivonne Figueroa", editor of the "El Boriuca: cultural magazine, women who were mothers carried their babies on their backs on a padded board that was secured to the baby's forehead.[3] Women did not dedicate themselves solely to cooking and the art of motherhood; many were also talented artists and made pots, grills, and griddles from river clay by rolling the clay into rope and then layering it to form or shape. Taíno women also carved drawings (petroglyphs) into stone or wood.[4] According to an observation made by doctor Diego Alvarez Chanca, who accompanied Columbus on his second voyage: "The Taina women made blankets, hammocks, petticoats (Naguas) of cloth and lace. She also weaved baskets."[5]

Single women walked around naked while married women wore a Nagua (na·guas), as petticoats were called, to cover their genitals."[6] The Naguas were a long cotton skirt which the woman made. The native women and girls wore the Naguas without a top. They were representative of each woman's status, the longer the skirt, the higher the woman's status.[4][6] Some Taíno women became notable caciques (tribal chiefs).[4] Such was the case of Yuisa (Luisa), a cacica in the region near Loíza, which was later named after her.[7]

Spanish colonial era (1493–1898)

The Spanish Conquistadores were soldiers who arrived to the island without women. This contributed to many of them marrying the native Taíno. The peace between the Spaniards and the Taínos was short-lived. The Spaniards took advantage of the Taínos' good faith and enslaved them, forcing them to work in the gold mines and in the construction of forts. Many Taínos died as a result either of the cruel treatment that they had received or of smallpox which became epidemic on the island. Other Taínos committed suicide or left the island after the failed Taíno revolt of 1511.[8] Some Taino women were raped by the Spaniards while others were taken as common-law wives, resulting in mestizo children.[9]

Spain encouraged the settlement of Puerto Rico by offering and making certain concessions to families who were willing to settle the new colony. Many farmers moved to the island with their families and together with the help of their wives developed the land's agriculture. High ranking government and military officials also settled the island and made Puerto Rico their home. The women in Puerto Rico were commonly known for their roles as mothers and housekeepers. They contributed to the household income by sawing and selling the clothes which they created. Women's rights were unheard of and their contributions to the island's society were limited. The island, which depended on an agricultural economy, had an illiteracy rate of over 80% at the beginning of the 19th century. Most women were home educated. The first library in Puerto Rico was established in 1642, in the Convent of San Francisco, access to its books was limited to those who belonged to the religious order.[10] The only women who had access to the libraries and who could afford books were the wives and daughters of Spanish government officials or wealthy land owners. Those who were poor had to resort to oral story-telling in what are traditionally known in Puerto Rico as Coplas and Decimas.[11]

Despite these limitations the women of Puerto Rico were proud of their homeland and helped defend it against foreign invaders. According to a popular Puerto Rican legend, when the British troops lay siege to San Juan, Puerto Rico the night of April 30, 1797, the townswomen, led by a bishop, formed a rogativa (prayer procession) and marched throughout the streets of the city singing hymns, carrying torches, and praying for the deliverance of the City. Outside the walls, particularly from the sea, the British navy mistook this torch-lit religious parade for the arrival of Spanish reinforcements. When morning arrived, the British were gone from the island, and the city was saved from a possible invasion.[12]

Women from Africa

The Spanish colonists, feared the loss of their Taino labor force due to the protests of Friar Bartolomé de las Casas at the council of Burgos at the Spanish Court. The Friar was outraged at the Spanish treatment of the Taíno and was able to secure their rights and freedom.[13] The colonists protested before the Spanish courts. They complained that they needed manpower to work in the mines, the fortifications and the thriving sugar industry. As an alternative, the Friar, suggested the importation and use of black slaves from Africa. In 1517, the Spanish Crown permitted its subjects to import twelve slaves each, thereby beginning the slave trade in their colonies.[14]

According to historian Luis M. Diaz, the largest contingent of African slaves came from the Gold Coast, Nigeria, and Dahomey, and the region known as the area of Guineas, the Slave Coast. However, the vast majority were Yorubas and Igbos, ethnic groups from Nigeria, and Bantus from the Guineas.[11]

Most African women were forced to work in the fields picking fruits and/or cotton. Those who worked in the master's house did so as maids or nannies. In 1789, the Spanish Crown issued the "Royal Decree of Graces of 1789", also known as "El Código Negro" (The Black code). In accordance to "El Código Negro" the slave could buy his freedom. Those who did became known as "freeman" or "freewoman".[15] On March 22, 1873, the Spanish National Assembly finally abolished slavery in Puerto Rico. The owners were compensated with 35 million pesetas per slave, and the former slaves were required to work for their former masters for three more years.[15][16]

The influence of the African culture began to make itself felt in the island. They introduced a mixture of Portuguese, Spanish, and the language spoken in the Congo in what is known as "Bozal" Spanish. They also introduced what became the typical dances of Puerto Rico such as the Bomba and the Plena which are likewise rooted in Africa. African women also contributed to the development of Puerto Rican cuisine which has a strong African influence. The melange of flavors that make up the typical Puerto Rican cuisine counts with the African touch. Pasteles, small bundles of meat stuffed into a dough made of grated green banana (sometimes combined with pumpkin, potatoes, plantains, or yautía) and wrapped in plantain leaves, were devised by African women on the island and based upon food products that originated in Africa.[17][18]

One of the first Afro-Puerto Rican women to gain notability was Celestina Cordero, a "freewoman", who in 1820, founded the first school for girls in San Juan. Despite the fact that she was subject to racial discrimination for being a black free women, she continued to pursue her goal to teach others regardless of their race and or social standing. After several years of struggling her school was officially recognized by the Spanish government as an educational institution. By the second half of the 19th century the Committee of Ladies of Honor of the Economical Society of Friends of Puerto Rico (Junta de Damas de Honor de la Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País) or the Association of Ladies for the Instruction of Women (Asociacion de Damas para la instruccion de la Mujer) were established.[19]

Women from non-Hispanic Europe

In the early 1800s, the Spanish Crown decided that one of the ways to curb pro-independence tendencies surfacing at the time in Puerto Rico was to allow Europeans of non-Spanish origin to settle the island. Therefore, the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 was printed in three languages, Spanish, English and French. Those who immigrated to Puerto Rico were given free land and a "Letter of Domicile" with the condition that they swore loyalty to the Spanish Crown and allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church. After residing in the island for five years the settlers were granted a "Letter of Naturalization" which made them Spanish subjects.[20]

Hundreds of women from Corsica, France, Ireland, Germany and other regions moved and settled in Puerto Rico with their families. These families were instrumental in the development of Puerto Rico's tobacco, cotton and sugar industries. Many of the women eventually intermarried into the local population, adopting the language and customs of their new homeland.[21] Their influence in Puerto Rico is very much present and in evidence in the island's cuisine, literature and arts.[22] The cultural customs and traditions of the women who immigrated to Puerto Rico from non-Hispanic nations blended in with those of the Taino, Spanish and African to become what is now the culture, customs and traditions of Puerto Rico.[23][24][25]

Early literary, civil, and political leaders

During the 19th century, women in Puerto Rico began to express themselves through their literary work. Among them was María Bibiana Benítez, Puerto Rico's first poet and playwright. In 1832, she published her first poem La Ninfa de Puerto Rico (The Nymph of Puerto Rico).[26] Her niece, Alejandrina Benitez de Gautier, whose own Aguinaldo Puertorriqueño (Ode to Puerto Rico) was published in 1843, has been recognized as one of the island's great poets.[27]

Puerto Rican women also expressed themselves against the political injustices practiced in the island against the people of Puerto Rico by the Spanish Crown. Some them embraced the revolutionary cause of Puerto Rican independence. The first Puerto Rican woman who is known to have become an Independentista and who struggled for Puerto Rico's independence from Spanish colonialism, was María de las Mercedes Barbudo. Joining forces with the Venezuelan government, under the leadership of Simon Bolivar, Barbudo organized an insurrection against Spanish rule in Puerto Rico.[28] However, her plans were discovered by the Spanish authorities, which resulted in her arrest and exile from Puerto Rico.

In 1868, many Puerto Rican women participated in the uprising known as El Grito de Lares.[29] Among the notable women who directly or indirectly participated in the revolt and who became part of Puerto Rican legend and lore were Lola Rodríguez de Tio and Mariana Bracetti. Lola Rodríguez de Tio believed in equal rights for women, the abolition of slavery and actively participated in the Puerto Rican Independence Movement. She wrote the revolutionary lyrics to La Borinqueña, Puerto Rico's national anthem.[30] Mariana Bracetti, also known as Brazo de Oro (Golden Arm), was the sister-in-law of revolution leader Manuel Rojas and actively participated in the revolt. Bracetti knitted the first Puerto Rican flag, the Lares Revolutionary Flag. The flag was proclaimed the national flag of the "Republic of Puerto Rico" by Francisco Ramírez Medina, who was sworn in as Puerto Rico's first president, and placed on the high altar of the Catholic Church of Lares.[31] Upon the failure of the revolution, Bracetti was imprisoned in Arecibo along with the other survivors, but was later released.[32]

American colonial era (1898–present)

Puerto Rico became an unincorporated territory of the United States or an American colony as defined by the United Nations decolonization committee after Spain ceded the island to the United States. This was in accordance with the Treaty of Paris of 1898 after the Spanish–American War.[33][34][35]

Soon after the U.S. assumed control of the island, the United States government believed that overpopulation of the island would lead to disastrous social and economic conditions, and instituted public policies aimed at controlling the rapid growth of the population.[36] To deal with this situation, in 1907 the U.S. instituted a public policy that gave the state the right "to sterilize unwilling and unwitting people". The passage of Puerto Rico Law 116 in 1937, codified the island government's population control program. This program was designed by the Eugenics Board and both U.S. government funds and contributions from private individuals supported the initiative. However, instead of providing Puerto Rican women with access to alternative forms of safe, legal and reversible contraception, the U.S. policy promoted the use of permanent sterilization. The US-driven Puerto Rican measure was so overly charged that women of childbearing age in Puerto Rico were more than 10 times more likely to be sterilized than were women from the U.S.[37]

From 1898 to 1917, many Puerto Rican women who wished to travel to the United States suffered discrimination. Such was the case of Isabel González, a young unwed pregnant woman who planned to find and marry the father of her unborn child in New York. Her plans were derailed by the United States Treasury Department, when she was excluded as an alien "likely to become a public charge" upon her arrival to New York City. González challenged the Government of the United States in the groundbreaking case Gonzales v. Williams (192 U.S. 1 (1904)). Officially the case was known as "Isabella Gonzales, Appellant, vs. William Williams, United States Commissioner of Immigration at the Port of New York" No. 225, argued December 4, 7, 1903, and decided January 4, 1904. Her case was an appeal from the Circuit Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York, filed February 27, 1903, after also having her Writ of Habeas Corpus (HC. 1–187) dismissed. Her Supreme Court case is the first time that the Court confronted the citizenship status of inhabitants of territories acquired by the United States. González actively pursued the cause of U.S. citizenship for all Puerto Ricans by writing and publishing letters in the New York Times.[38]

The Americanization process of Puerto Rico also hindered the educational opportunities for the women of Puerto Rico since teachers were imported from the United States and schools were not allowed to conduct their instruction using the Spanish language. Women who belonged to the wealthier families were able to attend private schools either in Spain or the United States, but those who were less fortunate worked as housewives, in domestic jobs, or in the so-called needle industry. Women such as Nilita Vientós Gastón, defended the use of the Spanish language in schools and in the courts of Puerto Rico, before the Supreme Court, and won.[39] Nilita Vientós Gaston was an educator, writer, journalist and later became the first female lawyer to work for the Department of Justice of Puerto Rico.[39]

Suffrage and women's rights

Women such as Ana Roque de Duprey opened the academic doors for the women in the island. In 1884, Roque was offered a teacher's position in Arecibo, which she accepted. She also enrolled at the Provincial Institute where she studied philosophy and science and earned her bachelor's degree. Roque de Duprey was a suffragist who founded "La Mujer", the first "women's only" magazine in Puerto Rico. She was one of the founders of the University of Puerto Rico in 1903.[40] From 1903 to 1923, three of every four University of Puerto Rico graduates were women passing the teachers training course to become teachers in the island's schools. Many women also worked as nurses, bearing the burden of improving public health on the island.

As in most countries, women were not allowed to vote in public elections. The University of Puerto Rico graduated many women who became interested in improving female influence in civic and political areas. This resulted in a significant increase in women who became teachers and educators but also in the emergence of female leaders in the suffragist and women rights movements. Among the women who became educators and made notable contributions to the educational system of the island were Dr. Concha Meléndez, the first woman to belong to the Puerto Rican Academy of Languages,[41][42][43] Pilar Barbosa, a professor at the University of Puerto Rico was the first modern-day Official Historian of Puerto Rico, and Ana G. Méndez founder of the Ana G. Mendez University System in Puerto Rico.[44]

The increase in women's rights of the early 1900s led to the first Puerto Rican women to work in positions traditionally occupied by men, including the first medical practitioners in the island. Drs. María Elisa Rivera Díaz and Ana Janer started their practices in 1909 and Dr. Palmira Gatell in 1910.[45] Ana Janer and María Elisa Rivera Díaz graduated in the same medical school class in 1909 and thus could both be considered the first female Puerto Rican physician.[46] These two and Palmira Gatell were followed by Dr. Dolores Mercedes Piñero, who earned her medical degree from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Boston in 1913.[47] In 1914, Rosa A. González earned a degree in nursing, established various health clinics throughout Puerto Rico and was the founder of The Association of Registered Nurses of Puerto Rico. González authored two books related to her field in which she denounced the discrimination against women and nurses in Puerto Rico. In her books she quoted the following:[48]

"In our country any man who is active in a political party, will be considered capable of handling an administrative position, regardless of how inept he is. "

"To this day the 'Medical Class' has not accepted nurses who have the same goal as doctors: the well-being of the patient. Both professions need each other in order to be successful."

In her book “Los hechos desconocidos” (The unknown facts) she denounced the corruption, abuses and unhealthy practices in the municipal hospital of San Juan. Gonzale’s publication convinced James R. Beverly, the Interim Governor of Puerto Rico, to sign Ley 77 (Law 77) in May 1930. The law established a Nurses Examining Board responsible for setting and enforcing standards of nursing education and practices. It also stipulated that the Board of Medical Examiners include two nurses. The passage of Ley 77 proved that women can operate both in the formal public sphere while working in a female oriented field.[49] In 1978, González became the first recipient of the Public Health Department of Puerto Rico Garrido Morales Award.[48]

In the early 1900s, women also became involved in the labor movement. During a farm workers' strike in 1905, Luisa Capetillo wrote propaganda and organized the workers in the strike. She quickly became a leader of the "FLT" (American Federation of Labor) and traveled throughout Puerto Rico educating and organizing women. Her hometown of Arecibo became the most unionized area of the country. In 1908, during the "FLT" convention, Capetillo asked the union to approve a policy for women's suffrage. She insisted that all women should have the same right to vote as men. Capetillo is considered to be one of Puerto Rico's first suffragists.[50] In 1912, Capetillo traveled to New York City where she organized Cuban and Puerto Rican tobacco workers. Later on, she traveled to Tampa, Florida, where she also organized workers. In Florida, she published the second edition of "Mi Opinión". She also traveled to Cuba and the Dominican Republic, where she joined the striking workers in their cause. In 1919, she challenged the mainstream society by becoming the first woman in Puerto Rico to wear pants in public. Capetillo was sent to jail for what was then considered to be a "crime", but the judge later dropped the charges against her. In that same year, along with other labor activists, she helped pass a minimum-wage law in the Puerto Rican Legislature.[51]

In 1929, Puerto Rican women who could read and write were enfranchised and in 1935 all adult women were enfranchised regardless of their level of literacy. Puerto Rico was the second Latin American country to recognize a woman's right to vote.[19] Both Dr. Maria Cadilla de Martinez and Ana María O'Neill were early advocates of women's rights. Cadilla de Martinez was also one of the first women in Puerto Rico to earn a doctoral (PhD) college degree.[52]

Early Birth Control

Dr. Clarence Gamble, an American physician, established a network of birth control clinics in Puerto Rico during the period of 1936 to 1939. He believed that Puerto Rican women and the women from other American colonies, did not have the mental capacity and were too poor to understand and use diaphragms for birth control as the women in the United States mainland. He inaugurated a program funded by the Rockefeller Foundation which would replace the use of diaphragms with foam powders, cremes and spermicidal jellies. He did not know that in the past Rosa Gonzalez had publicly battled with prominent physicians and named her and Carmen Rivera de Alvarez, another nurse who was a Puerto Rican independence advocate, to take charge of the insular birth control program. However, the insular program lacked funding and failed.[53]

Puerto Rican women in the U.S. military

In 1944, the U.S. Army sent recruiters to the island to recruit no more than 200 women for the Women's Army Corps (WAC). Over 1,000 applications were received for the unit which was to be composed of only 200 women. The Puerto Rican WAC unit, Company 6, 2nd Battalion, 21st Regiment of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, a segregated Hispanic unit, was assigned to the New York Port of Embarkation, after their basic training at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. They were assigned to work in military offices which planned the shipment of troops around the world.[54] Among them was PFC Carmen García Rosado, who in 2006, authored and published a book titled "LAS WACS-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Segunda Guerra Mundial" (The WACs-The participation of the Puerto Rican women in the Second World War), the first book to document the experiences of the first 200 Puerto Rican women who participated in said conflict.[55]

That same year the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) decided to accept Puerto Rican nurses so that Army hospitals would not have to deal with the language barriers.[56] Thirteen women submitted applications, were interviewed, underwent physical examinations, and were accepted into the ANC. Eight of these nurses were assigned to the Army Post at San Juan, where they were valued for their bilingual abilities. Five nurses were assigned to work at the hospital at Camp Tortuguero, Puerto Rico. Among them was Second Lieutenant Carmen Lozano Dumler, who became one of the first Puerto Rican female military officers.[54]

Not all the women served as nurses: some served in administrative duties in the mainland or near combat zones. Such was the case of Technician Fourth Grade Carmen Contreras-Bozak who belonged to the 149th Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. The 149th Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) Post Headquarters Company was the first WAAC Company to go overseas, setting sail from New York Harbor for Europe on January 1943. The unit arrived in Northern Africa on January 27, 1943 and rendered overseas duties in Algiers within General Dwight D. Eisenhower's theater headquarters, T/4. Carmen Contreras-Bozak, a member of this unit, was the first Hispanic to serve in the U.S. Women's Army Corps as an interpreter and in numerous administrative positions.[56][57]

Another was Lieutenant Junior Grade María Rodríguez Denton, the first woman from Puerto Rico who became an officer in the United States Navy as member of the WAVES. The Navy assigned LTJG Denton as a library assistant at the Cable and Censorship Office in New York City. It was LTJG Denton who forwarded the news (through channels) to President Harry S. Truman that the war had ended.[56]

Some Puerto Rican women who served in the military went on to become notable in fields outside of the military. Among them are Sylvia Rexach, a composer of boleros, Marie Teresa Rios, an author, and Julita Ross, a singer.

Sylvia Rexach, dropped-out of the University of Puerto Rico in 1942 and joined the United States Army as a member of the WACS where she served as an office clerk. She served until 1945, when she was honorably discharged.[58] Marie Teresa Rios was a Puerto Rican writer who also served in World War II. Rios, mother of Medal of Honor recipient, Capt. Humbert Roque Versace and author of The Fifteenth Pelican which was the basis for the popular 1960s television sitcom "The Flying Nun", drove Army trucks and buses. She also served as a pilot for the Civil Air Patrol. Rios Versace wrote and edited for various newspapers around the world, including places such as Guam, Germany, Wisconsin, and South Dakota, and publications such the Armed Forces Star & Stripes and Gannett.[59] During World War II, Julita Ross entertained the troops with her voice in "USO shows" (United Service Organizations).[60]

Military leadership positions and combat

Changes within the policy and military structure of the U.S. armed forces helped expand the participation and roles for women in the military, among these the establishment of the All-Volunteer Force in the 1970s. Puerto Rican women and women of Puerto Rican descent have continued to join the Armed Forces, and some have even made the military a career. Among the Puerto Rican women who have or had high ranking positions are the following:

Colonel Maritza Sáenz Ryan (U.S. Army), the head of the Department of Law at the United States Military Academy. She is the first woman and first Hispanic West Point graduate to serve as an academic department head. She also has the distinction of being the most senior-ranking Hispanic Judge Advocate.[61][62] As of June 15, 2011, Colonel Maria Zumwalt (U. S. Army) served as commander of the 48th Chemical Brigade.[63] Captain Haydee Javier Kimmich (U.S. Navy) from Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico was the highest-ranking Hispanic female in the Navy. Kimmich was assigned as the Chief of Orthopedics at the Navy Medical Center in Bethesda. She reorganized their Reservist Department during Operation Desert Storm. In 1998, she was selected as the woman of the year in Puerto Rico.[47] Lieutenant Colonel Olga E. Custodio (USAF) became the first Hispanic female U.S. military pilot. She holds the distinction of being first Latina to complete U.S. Air Force military pilot training. Upon retiring from the military, she became the first Latina commercial airline captain.[64] Major Sonia Roca was the first Hispanic female officer to attend the Command and General Staff Officer Course at the Army's School of the Americas.[47]

Puerto Rican servicewomen were among the 41,000 women who participated in Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm. They also served in the battlefields of Afghanistan and Iraq where the first four Puerto Rican women perished in combat.

The first female soldier of Puerto Rican descent to die in a combat zone was SPC Frances M. Vega.,[65] SPC Lizbeth Robles, was the first female soldier born in Puerto Rico to die in the War on Terrorism.,[66] SPC Aleina Ramirez Gonzalez[67] and Captain Maria Ines Ortiz, was the first Hispanic nurse to die in combat and first Army nurse to die in combat sice the Viet Nam War.[68]

The names of the four women are engraved in El Monumento de la Recordación (The Monument of Remembrance), which is dedicated to Puerto Rico's fallen soldiers and situated in front of the Capitol Building in San Juan, Puerto Rico.[69]

In July 2015, Puerto Rico Governor Alejandro Garcia Padilla nominated Colonel Martha Carcana for the position of Adjutant General of the Puerto Rican National Guard, a position which she unofficially held since 2014. On September 4, 2015, she was confirmed as the first Puerto Rican woman to lead the Puerto Rican National Guard.[70][71]

Puerto Rican women in the revolt against United States rule

In the 1930s, the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party became the largest independence group in Puerto Rico. Under the leadership of Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos, the party opted against electoral participation and advocated violent revolution. The women's branch of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party was called the Daughters of Freedom. Some of the militants of this women's-only organization included Julia de Burgos, one of Puerto Rico's greatest poets.[72][73]

Various confrontations took place in the 1930s in which Nationalist Party partisans were involved and which led to a call for an uprising against the United States and the eventual attack of the United States House of Representatives of the 1950s. One of the most violent incidents was the 1937 Ponce massacre, in which police officers fired upon Nationalists who were participating in a peaceful demonstration against American abuse of authority. About 100 civilians were wounded and nineteen were killed, among them, a woman, Maria Hernández del Rosario, and a seven-year-old child, Georgina Maldonado.[74]

On October 30, 1950, the Nationalist Party called for a revolt against the United States. Known as the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party Revolts of the 1950s, uprisings were held in the towns of Ponce, Mayagüez, Naranjito, Arecibo, Utuado, San Juan and most notably in Jayuya which became known as the Jayuya Uprising. Various women who were members of the Nationalist Party, but who did not participate in the revolts were falsely accused by the US Government of participating in the revolts and arrested. Among them Isabel Rosado, a social worker and Dr. Olga Viscal Garriga, a student leader and spokesperson of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party's branch in Río Piedras.[75] Other women who were leaders of the movement were Isabel Freire de Matos, Isolina Rondón and Rosa Collazo.

The military intervened and the revolts came to an end after three days on September 2. Two of the most notable women, who bore arms against the United States, were Blanca Canales and Lolita Lebrón.

Blanca Canales is best known for leading the Jayuya Revolt. Canales led her group to the town's plaza where she raised the Puerto Rican flag and declared Puerto Rico to be a Republic. She was arrested and accused of killing a police officer and wounding three others. She was also accused of burning down the local post office. She was sentenced to life imprisonment plus sixty years of jail. In 1967, Canales was given a full pardon by Puerto Rican Governor Roberto Sanchez Vilella.[76]

Lolita Lebrón was the leader of a group of nationalists who attacked the United States House of Representatives in 1954. Lebrón's mission was to bring world attention to Puerto Rico's independence cause. When Lebrón's group reached the visitor's gallery above the chamber in the House, she stood up and shouted "¡Viva Puerto Rico Libre!" ("Long live a Free Puerto Rico!") and unfurled a Puerto Rican flag. Then the group opened fire with automatic pistols. A popular legend claims that Lebrón fired her shots at the ceiling and missed. In 1979, under international pressure, President Jimmy Carter pardoned Lolita Lebrón and two members of her group, Irving Flores and Rafael Cancel Miranda.[77]

The Great Migration

The 1950s saw a phenomenon that became known as the "The Great Migration", where thousands of Puerto Ricans, including entire families of men, women and their children, left the Island and moved to the states, the bulk of them to New York City. Several factors led to the Migration, among them the Great Depression of the 1930s, World War II in the 1940s, and the advent of commercial air travel in the 1950s.[79]

The Great Depression which spread throughout the world was also felt in Puerto Rico. Since the island's economy has been dependent on the economy of the United States, when American banks and industries began to fail the effect was also felt in the island. Unemployment was on the rise as a consequence and many families fled to the mainland U.S. in search of jobs.[80]

The outbreak of World War II, opened the doors to many of the migrants who were searching for jobs. Since a large portion of the male population of the U.S. was sent to war, there was a sudden need of manpower to fulfill the jobs left behind. Puerto Ricans, both male and female, found themselves employed in factories and ship docks, producing both domestic and warfare goods. The new migrants gained the knowledge and working skills that became useful even after the war had ended. For the first time the military also provided a steady source of income for women.[54][81]

The advent of air travel provided Puerto Ricans with an affordable and faster way of travel to New York and other cities in the U.S.. One of the things that most of the migrants had in common was that they wanted a better way of life than was available in Puerto Rico and although each held personal reasons for migrating their decision generally was rooted in the island's impoverished conditions as well as the public policies that sanctioned migration. One of the migrants was Dr. Antonia Pantoja. Pantoja's was an educator, social worker, feminist, civil rights leader, founder of the Puerto Rican Forum, Boricua College, Producir and founder of ASPIRA. ASPIRA (Spanish for "aspire") is a non-profit organization that promoted a positive self-image, commitment to community, and education as a value as part of the ASPIRA Process to Puerto Rican and other Latino youth in New York City. In 1996, President Bill Clinton presented Dr. Pantoja with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, making her the first Puerto Rican woman to receive this honor.[82][83][84]

Another Puerto Rican woman whose actions affected the United States educational system was Felicitas Mendez (maiden name: Gomez). Mendez, a native of the town of Juncos, became an American civil rights pioneer with her husband Gonzalo, when their children were denied the right to attend an all "white" school in Southern California. In 1946, Mendez and her husband took it upon themselves the task of leading a community battle that changed the educational system in California and set an important legal precedent for ending de jure segregation in the United States. The landmark desegregation case, known as the Mendez v. Westminster case,[85] paved the way for integration and the American civil rights movement.[86]

Women in the fine arts

Before the introduction of the cinema and television in Puerto Rico, there was opera. Opera was one of the main artistic menus in which Puerto Rican women have excelled. One of the earliest opera soprano's in the island was Amalia Paoli, the sister of Antonio Paoli. In the early 19th century, Paoli performed at the Teatro La Perla in the city of Ponce in Emilio Arrieta's opera "Marina".[87] The first Puerto Rican to sing a lead role at the New York Metropolitan Opera was Graciela Rivera. She played the role of "Lucia" in the December 1951 production of Lucia di Lammermoor.[88] Other women who excelled as opera soprano's are Ana María Martínez,[89] Melliangee Pérez, who was awarded the "Soprano of the Year" award by UNESCO,[90] Irem Poventud, the first Puerto Rican to perform in the San Francisco Opera House,[91] and Margarita Castro Alberty, the recipient of the prestigious Rockefeller Foundation, Baltimore Opera Guild, Chicago Opera Guide and Metropolitan Opera Guild awards.[92]

Women played an important role as pioneers of Puerto Rico's television industry. Lucy Boscana founded the Puerto Rican Tablado Company, a traveling theater. Among the plays which she produced with the company was "The Oxcart" by fellow Puerto Rican playwright René Marqués. She presented the play in Puerto Rico and on Off-Broadway in New York City. On August 22, 1955, Boscana became a pioneer in the television of Puerto Rico when she participated in Puerto Rico's first telenovela (soap opera) titled "Ante la Ley", alongside fellow television pioneer Esther Sandoval. The soap opera was broadcast in Puerto Rico by Telemundo.[93] Among the other television pioneers were Awilda Carbia and Gladys Rodríguez. Sylvia del Villard was an actress, dancer, choreographer and one of the first Afro-Puerto Rican activists.[94] In the cinema industry Marquita Rivera was the first Puerto Rican actress to appear in a major Hollywood motion picture when she was cast in Road to Rio.[95] Other women from Puerto Rico who have succeeded in the United States as actresses include Míriam Colón, founder of The Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre and recipient of an "Obie Award" for "Lifetime Achievement in the Theater." Colón debuted as an actress in "Peloteros" (Baseball Players), a film produced in Puerto Rico starring Ramón (Diplo) Rivero, in which she played the character of "Lolita."[96] and Rita Moreno, the first Latin woman to win an Oscar, an Emmy, a Grammy and a Tony.[97]

The decade of the 1950s witnessed a rise of composers and singers of typical Puerto Rican music and the Bolero genre. Women such as Ruth Fernández,[98] Carmita Jiménez, Sylvia Rexach[99] and Myrta Silva[100] were instrumental in the exportation and internationalization of Puerto Rico's music. Among the women who have contributed to the island's contemporary popular music are Nydia Caro one of the first winners of the prestigious "Festival de Benidorm" in Valencia, Spain, with the song "Vete Ya", composed by Julio Iglesias,[101] Lucecita Benítez winner of the Festival de la Cancion Latina (Festival of the Latin Song) in Mexico,[102] Olga Tañón earner of two Grammy Awards, three Latin Grammy Awards, and 28 Premios Lo Nuestro Awards[103][104] and Martha Ivelisse Pesante Rodríguez known as "Ivy Queen". Jennifer Lopez a.k.a. "J-Lo" is an entertainer, businesswoman, philanthropist and producer who was born in New York. She is proud of her Puerto Rican heritage and is regarded by "Time Magazine" as the most-influential Hispanic performer in the United States and one of the 25 most influential Hispanics in America.[105][106] As a philanthropist she launched a telemedicine center in San Juan, Puerto Rico, at the San Jorge Children's Hospital and has plans to launch a second one at the University Pediatric Hospital at the Centro Medico.[107]

Women empowerment

In the 1950s and 60's with the industrialization of Puerto Rico, women's job shifted from factory workers to that of professionals or office workers. Among the factors which influenced the role which women played in the industrial development of Puerto Rico was that the divorce rate was high and some women became the sole economic income source of their families. The feminist and women rights movements have also contributed to empowerment of women in the fields of politics, science and business.[108] Among the notable women involved in politics in Puerto Rico are Felisa Rincón de Gautier, also known as Doña Fela. She ran for and was elected mayor of San Juan in 1946, becoming the first woman to have been elected mayor of a capital city in the all of the Americas.[109] María Luisa Arcelay was the first woman in Puerto Rico and in all of Latin America to be elected to a government legislative body.[110] and Sila M. Calderón, former mayor of San Juan, became in November 2000, the first woman governor of Puerto Rico. On November 8, 2016 former Speaker of the House Jenniffer Gonzalez became the first woman and youngest person to be elected Resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico in the U.S. Congress in the 115 years since the seat had been created. Their empowerment was not only limited to Puerto Rico. In the United States Nydia Velázquez was the first Puerto Rican congresswoman and Chair of House Small Business Committee and Dr. Antonia Coello Novello became the first Latino and first woman U.S. Surgeon General (1990–93),[111]

With the advances in medical technologies and the coming of the Space Age of the 20th century, Puerto Rican women have expanded their horizons and have made many contributions in various scientific fields, among them the fields of aerospace and medicine.

Puerto Rican women, have reached top positions in NASA, serving in sensitive leadership positions. Nitza Margarita Cintron was named Chief of NASA's Johnson Space Center Space Medicine and Health Care Systems Office in 2004.[112] Other women involved in the United States Space Program are Mercedes Reaves Research engineer and scientist responsible for the design of a viable full-scale solar sail and the development and testing of a scale model solar sail at NASA Langley Research Center; Monserrate Román a microbiologist who participated in the building of the International Space Station and Mercedes Reaves a research engineer and scientist responsible for the design of a viable full-scale solar sail and the development and testing of a scale model solar sail at NASA Langley Research Center. Dr. Yajaira Sierra Sastre was chosen to take part in 2013 in a new NASA project called "HI-SEAS," an acronym for "Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation,” that will help to determine why astronauts don't eat enough, having noted that they get bored with spaceship food and end up with problems like weight loss and lethargy that put their health at risk. She lived for four months (March – August 2013) isolated in a planetary module to simulate what life will be like for astronauts at a future base on Mars at a base in Hawaii. Sierra Sastre hopes to become the first Puerto Rican female astronaut,[113][114]

Among those who have triumphed as businesswoman are Carmen Ana Culpeper who served as the first female Secretary of the Puerto Rico Department of the Treasury during the administration of Governor Carlos Romero Barceló and later served as the president of the then government-owned Puerto Rico Telephone Company during the governorship of Pedro Rosselló,[115] Camalia Valdés the President and CEO of Cerveceria India, Inc., Puerto Rico's largest brewery.[116] and Carlota Alfaro, a high fashion designer[117] known as "Puerto Rico's grande dame of fashion".[118]

Historians, such as Dra. Delma S. Arrigoitia, have written books and documented the contributions which Puerto Rican women have made to society. Arrigoitia was the first person in the University of Puerto Rico to earn a master's degree in the field of history. In 2012, she published her book "Introduccion a la Historia de la Moda en Puerto Rico". The book, which was requested by the Puerto Rican high fashion designer Carlota Alfaro, covers over 500 years of history of the fashion industry in Puerto Rico. Arrigoitia is working on a book about the women who have served in the Puerto Rican Legislature, as requested by the former President of the Chamber of Representatives, Jenniffer González.[119]

In May 2009, President Barack Obama nominated Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court following the retirement of Justice David Souter. Her nomination was confirmed by the Senate in August 2009 by a vote of 68–31. Sotomayor has supported, while on the court, the informal liberal bloc of justices when they divide along the commonly perceived ideological lines. During her tenure on the Supreme Court, Sotomayor has been identified with concern for the rights of defendants, calls for reform of the criminal justice system, and making impassioned dissents on issues of race, gender and ethnic identity.[120]

Women's week in Puerto Rico

On June 2, 1976, the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico approved law number 102 which declared every March 2 "Día Internacional de la Mujer" (International Women's Day) as a tribute to the Puerto Rican women. However, the government of Puerto Rico decided that it would only be proper that a week instead of a day be dedicated in tribute to the accomplishments and contributions of the Puerto Rican women. Therefore, on September 16, 2004, the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico passed law number 327 which declares the second week of the month of March the "Semana de la Mujer en Puerto Rico" (Women's week in Puerto Rico).[121]

Puerto Rican women

Not only have Puerto Rican women have excelled in many fields, such as business, politics, and science, they have also represented their country in other international venues such as beauty contests and sports. Some have been honored by the United States government for their contributions to society. Some of these contributions are described in the following paragraphs.

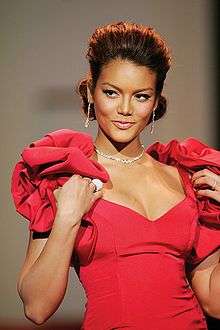

Beauty pageants

Five Puerto Rican women have won the title of Miss Universe and one the title of Miss World. Miss Universe is an annual international beauty contest that is run by the Miss Universe Organization. Along with the Miss Earth and Miss World contests, Miss Universe is one of the three largest beauty pageants in the world in terms of the number of national-level competitions to participate in the world finals[122] The first Puerto Rican woman to be crowned "Miss Universe" was Marisol Malaret Contreras in 1970.[123] She was followed by Deborah Carthy-Deu(1985), Dayanara Torres ( 1993), Denise Quiñones (2001) and Zuleyka Rivera (2006). Wilnelia Merced is the first and to date the only Puerto Rican Miss World (1975).

Inventors

Olga D. González-Sanabria, a member of the Ohio Women's Hall of Fame, contributed to the development of the "Long Cycle-Life Nickel-Hydrogen Batteries" which helps enable the International Space Station power system.[124]

Ileana Sánchez, a graphic designer, invented a book for the blind that brings together art and braille. Ms. Sanchez used a new technique called TechnoPrint and TechnoBraille. Rather than punch through heavy paper to create the raised dots of the Braille alphabet for the blind, these techniques apply an epoxy to the page to create not only raised dots, but raised images with texture. The epoxy melds with the page, becoming part of it, so that you can't scrape it off with your fingernail. The images are raised so that a blind person can feel the artwork and in color, not just to attract the sighted family who will read the book with blind siblings or children, but also for the blind themselves. The book "Art & the Alphabet, A Tactile Experience" is co-written with Rebecca McGinnis of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met has already incorporated the book into their Access program.[125]

Journalists

Various Puerto Rican women have excelled in the field of journalism in Puerto Rico and in the United States, among them: Carmen Jovet, the first Puerto Rican woman to become a news anchor in Puerto Rico, Bárbara Bermudo, co-host of Primer Impacto, and María Celeste Arrarás, anchorwoman for Al Rojo Vivo.[126]

Religion

Among the Puerto Rican women who became notable religious leaders in Puerto Rico are Sor Isolina Ferré Aguayo and Juanita Garcia Peraza, a.k.a. "Mita".

Sor Isolina Ferré Aguayo, a Roman Catholic nun, was the founder of the Centros Sor Isolina Ferré in Puerto Rico. The center revolved around a concept designed by Ferré originally known as "Advocacy Puerto Rican Style". The center worked with juvenile delinquents, by suggesting that they should be placed under custody by their community and that they should be treated with respect instead of as criminals. This method gathered interest from community leaders in the United States, who were interested in establishing similar programs.[127]

Juanita Garcia Peraza, better known as Mita, founded the Mita Congregation, the only non-Catholic denomination religion of Puerto Rican origin. Under Perazas' leadership, the church founded many small businesses which provided work, orientation, and help for its members. The church has expanded to Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, Panama, El Salvador, Canada, Curaçao, Ecuador and Spain.[128][129]

Sports

Among the women who have represented Puerto Rico in international sports competitions is Rebekah Colberg, known as "The Mother of Puerto Rican Women's Sports". Colberg participated in various athletic competitions in the 1938 Central American and Caribbean Games where she won the gold medals in discus and javelin throw.[130] Angelita Lind, a track and field athlete, participated in three Central American and Caribbean Games (CAC) and won two gold medals, three silver medals, and one bronze medal. She also participated in three Pan American Games and in the 1984 Olympics.[131][132] Anita Lallande, a former Olympic swimmer, holds the island record for most medals won at CAC Games with a total of 17 medals, 10 of them being gold medals.[133]

Laura Daniela Lloreda is a Puerto Rican who represented Mexico at various international women's volleyball competitions and played professional volleyball both in Mexico and in Puerto Rico,[134] and Ada Velez is a Puerto Rican former boxer who became the country's first professional women's world boxing champion.[135]

Recognized by the United States government

The United States government has honored the achievements of seven Puerto Rican women (including those of Puerto Rican descent) and awarded them either the Presidential Medal of Freedom or the Presidential Citizens Medal, the highest civilian decorations of the United States.

Five Puerto Rican women have been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, an award bestowed by the President of the United States which is considered the highest civilian award in the United States. The medal recognizes those individuals who have made "an especially meritorious contribution to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, cultural or other significant public or private endeavors".[136][137] The following Puerto Rican women have been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom:

- Antonia Pantojas - educator, social worker, feminist, civil rights leader

- Chita Rivera - actress, dancer, and singer

- Isolina Ferré - nun

- Rita Moreno - actress, singer, and EGOT recipient

- Sylvia Mendez - civil rights activist

Two Puerto Rican women have been awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal, an award bestowed by the President of the United States which is considered the second highest civilian award in the United States, second only to the Presidential Medal of Freedom mentioned before. The medal recognizes individuals "who have performed exemplary deeds or services for his or her country or fellow citizens."[138] The following Puerto Rican women have been awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal:

- Helen Rodriguez-Trias - pediatrician, educator, and leader in public health

- Victoria Leigh Soto - educator

U.S. Postal Service Commemorative Stamps

Two women have been honored by the U.S. Postal Service Commemorative Stamp Program. On April 14, 2007, the U.S. Postal Service unveiled a stamp commemorating the Mendez v. Westminster case.[139][140] The unveiling took take place during an event at Chapman University School of Education, Orange County, California, commemorating the 60th anniversary of the landmark case.[141] Featured on the stamp are Felicitas Mendez, a native of Juncos, Puerto Rico[142] and her husband, Gonzalo. On September 14, 2010, in a ceremony held in San Juan, the United States Postal Service honored Julia de Burgos's life and literary work with the issuance of a first class postage stamp, the 26th release in the postal system's Literary Arts series.[143][144]

Gallery

Helen Rodriguez Trias

Helen Rodriguez Trias

Pediatrician, first Latina president of the American Public Health Association, recipient of the Presidential Citizens Medal

.jpg)

Further reading

- LAS WACS-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Seginda Guerra Mundial; by: Carmen Garcia Rosado; 1ra. Edicion publicada en Octubre de 2006; 2da Edicion revisada 2007; Registro Propiedad Intectual ELA (Government of Puerto Rico) #06-13P-)1A-399; Library of Congress TXY 1-312-685.

- La lucha por el sufragio femenino en Puerto Rico, 1896–1935; by: María de Fátima Barceló Miller; Published 1997 by Centro de Investigaciones Sociales,Ediciones Huracán in San Juan, P.R, Río Piedras, P.R.; ISBN 0-929157-45-1.

- La Mujer Puertorriqueña, su vida y evolucion a través de la historia; Published 1972 by Plus Ultra Educational Publishers in New York; Open Library: OL16223237M.

- La Mujer Negra En La Literatura Puertorriquena/ The Black Women In Puerto Rican Literature: Cuentistica De Los Setenta/ Storytellers Of The Seventies; by: Marie Ramos Rosado; Publisher: Univ Puerto Rico Pr; ISBN 978-0-8477-0366-1.

- Introduccion a la Historia de la Moda en Puerto Rico by: Delma S. Arrigoitia; Publisher: EDITORIAL PLAZA MAYOR (2012); ISBN 978-1-56328-376-5

- Remedios: Stories of Earth and Iron from the History of Puertorriquenas; by: Aurora Levins Morales; Publisher: South End Press; ISBN 978-0-89608-644-9

- Women, Creole Identity, and Intellectual Life in Early Twentieth-Century Puerto Rico; By Magali Roy-Féquière, Juan Flores, Emilio Pantojas-García; Published by Temple University Press, 2004; ISBN 1-59213-231-6, ISBN 978-1-59213-231-7

- Further reading: Reproducing Empire: Race, Sex, Science, and U.S. Imperialism in Puerto Rico; By Laura Briggs; Publisher: University of California Press; ISBN 0520232585; ISBN 978-0520232587

See also

- Puerto Rican women in the military

- List of Puerto Rican military personnel

- Puerto Ricans in World War II

References

- ↑ 2010 US Census

- 1 2 Introduction, Puerto Rican Labor Movement, Retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ "Taínos"; by: Ivonne Figueroa; July 1996

- 1 2 3 "The Tainos"; by Francine Jacobs (Author); Publisher: Putnam Juvenile; ISBN 0-399-22116-6; ISBN 978-0-399-22116-3

- ↑ "Introduccion a la Historia de la Moda en Puerto Rico"' by: Delma S. Arrigoitia; Publisher:, Pg. 13; EDITORIAL PLAZA MAYOR (2012); ISBN 978-1-56328-376-5, retrieved October 3, 2013

- 1 2 Rivera, Magaly. "Taíno Indians Culture". Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ↑ The Last Taino Queen, Retrieved September 19, 2007

- ↑ Boriucas Illustres, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ↑ Guitat, Lynne. "Criollos: The Birth of a Dynamic New Indo-Afro-European People and Culture on Hispaniola.". KACIKE: Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2011.

- ↑ Kamellos, "Chronolgy of Hispnaic American History", p.48

- 1 2 "Puerto Rico: desde sus orígenes hasta el cese de la dominación española"; by: Luis M. Díaz Soler; Publisher:Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1994; Original from University of Texas; ISBN 0-8477-0177-8; ISBN 978-0-8477-0177-3, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Lindsay Dean, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ "Bartolomé de las Casas", Oregon State University, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ↑ Bartolomé de las Casas. Oregon State University, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- 1 2 (Spanish) "El Codigo Negro" (The Black Code). 1898 Sociedad de Amigos de la Historia de Puerto Rico. Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ↑ Abolition of Slavery in Puerto Rico retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Puerto Rico, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ↑ Pasteles not tasteless: the flavor of Afro-Puerto Rico – wrapped plantain-dough stuffed meat pastries: includes recipes and notes on food tours in Puerto Rico, retrieved October 3, 2013

- 1 2 A Modern Historical Perspective of Puerto Rican Women : Puerto Rican Women Movement beyond the region politics

- ↑ Archivo General de Puerto Rico: Documentos, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Corsican immigration to Puerto Rico, Retrieved July 31, 2007

- ↑ Puerto Rican Cuisine & Recipes

- ↑ Puerto Rico Convention Center. "Puerto Rico: Culture". About Puerto Rico., retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ ""Puerto Rico: Culture", Puerto Rico Convention Center.". Archived from the original on January 2, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- ↑ Morales Carrión, Arturo (1983). Puerto Rico: A Political and Cultural History. New York: Norton & Co.

- ↑ La Ninfa de Puerto Rico a la Justicia, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Mariana Bracetti, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Mercedes – La primera Independentista Puertorriquena, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Moscoso, Francisco, La Revolución Puertorriqueña de 1868: El Grito de Lares, Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, 2003

- ↑ Toledo, Josefina, Lola Rodríguez de Tió – Contribución para un estudio integral, Librería Editorial Ateneo, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2002, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ The Flag of Lares

- ↑ "Mariana Bracetti". Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- ↑ UN Decolonization Panel

- ↑ Puerto Rico History Retrieved September 3, 2008

- ↑ Safa, Helen (March 22, 2003). "Changing forms of U.S. hegemony in Puerto Rico: the impact on the family and sexuality". Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ↑ Birth Control: Sterilization Abuse., retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Sterilization Abuse; Katherine Krase and originally published in the Jan/Feb 1996 newsletter of the National Women's Health Network retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Erman, Sam (Summer 2008). "Meanings of Citizenship in the U.S. Empire: Puerto Rico, Isabel Gonzalez, and the Supreme Court, 1898 to 1905". Journal of American Ethnic History. 27 (4).

- 1 2 El Nuevo Día

- ↑ Ana Roque

- ↑ Salon Hogar

- ↑ Casa Biblioteca Concha Meléndez

- ↑ El Nuevo Dia

- ↑ LEY 45 25 DE JULIO DE 1997, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ "La Mujer en las Profesiones de Salud (1898–1930); By: Yamila Azize Vargas and Luis Alberto Aviles; PRHSJ Vol. 9, No. 1

- ↑ http://prhsj.rcm.upr.edu/index.php/prhsj/article/viewFile/715/558

- 1 2 3 Women's Military Memorial, retrieved October 3, 2013

- 1 2 Salud Promujer 1, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Advancing The Kingdom Missionaries And Americanization In Puerto Rico, 1898 – 1930s; By: Ellen Walsh; Pages 171-188; Publisher: ProQuest, UMI Dissertation Publishing; ISBN 1243978023; ISBN 9781243978028

- ↑ History, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Luisa Capetillo Perone, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Biografias-Maria O'Neill, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Reproducing Empire: Race, Sex, Science, and U.S. Imperialism in Puerto Rico

- 1 2 3 Puerto Rican Woman in Defense of our country

- ↑ "LAS WACS"-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Segunda Guerra Mundial; by: Carmen Garcia Rosado; page 60; 1ra. Edicion publicada en Octubre de 2006; 2da Edicion revisada 2007; Registro Propiedad Intelectual ELA (Government of Puerto Rico) #06-13P-1A-399; Library of Congress TXY 1-312-685.

- 1 2 3 Bellafaire, Judith. "Puerto Rican Servicewomen in Defense of the Nation". Women in Military Service For America Memorial Foundation. Retrieved October 10, 2006.

- ↑ Kennon, Katie. "Young woman's life defined by service in Women's Army Corps". US Latinos and Latinas & World War II. Archived from the original on September 19, 2006. Retrieved October 10, 2006.

- ↑ Music of Puerto Rico

- ↑ Marie Teresa Rios, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Popular Culture, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Maritza Sáenz Ryan - Bio.

- ↑ Ryan takes charge of Law Department

- ↑ Zumwalt assumes 48th Chemical Brigade command

- ↑ Our American Dream: Meet the First Latina US Military Pilot

- ↑ Washington Post

- ↑ Fallen Heroes Memorial

- ↑ Honor the Fallen

- ↑ Arlington National Cemetery

- ↑ Memorial Day Speech

- ↑ Designan nuevamente a Martha Carcana para dirigir la Guardia Nacional

- ↑ National Guard News

- ↑ Julia de Burgos-Bio., retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Latin America Today, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Albizu Campos and the Ponce Massacre, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Viscal Family

- ↑ Blanca Canales, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ A 2004 Washington Post article on Lolita's life, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Women making brassieres at the Jem Manufacturing Corp. in Puerto Rico, March 1950. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ↑ Puerto Rican Emigration: Why the 1950s?, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ "Great Depressions of the Twentieth Century, edited by T. J. Kehoe and E. C. Prescott". Greatdepressionsbook.com. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ↑ "LAS WACS"-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Seginda Guerra Mundial; by: Carmen Garcia Rosado; page 60; 1ra. Edicion publicada en Octubre de 2006; 2da Edicion revisada 2007; Registro de la Propiedad Intectual ELA (Government of Puerto Rico) #06-13P-)1A-399; Library of Congress TXY 1-312-685.

- ↑ Our Founder, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Louis University

- ↑ NASW retrieved, October 3, 2013

- ↑ Geisler, Lindsey (September 11, 2006). "Mendez case paved way for Brown v. Board". Topeka Capital-Journal. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Sauceda, Isis (March 28, 2007). "Cambio Historico (Historic Change)". People en Espanol (in Spanish): 111–112.

- ↑ PRPOP

- ↑ Certificates – Graciela Rivera Zumchak: Obituary. Times Leader. (15 N. Main Street Wilkes-Barre, PA 18711) July 20, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ↑ www.hispaniconline.com Feature Opera Lady Ana María Martínez, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Laura Rey: Soprano From Puerto Rico Wins Met's Gulf Coast Regional Finals; National Semifinals Next For 22-Year-Old. Keith Marshall. PuertoRico-Herald. February 17, 2003. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ↑ San Francisco Opera Performance Archive, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Proyecto Salon Hogar, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Fundacion Nacional para la Cultura Popular

- ↑ Puerto Rican Popular Culture

- ↑ Marquita Rivera

- ↑ Miriam Colon, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Speakers on healthcare, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Biografías: Ruth Fernández. Fundación Nacional para la Cultura Popular. 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ↑ Punto Fijo, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Puerto Rican popular culture site, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Bonacich, Drago. "Biography: Nydia Caro". Allmusic. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ↑ Online Discography

- ↑ Grammy awards, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Latin Grammy awards, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Jennifer Lopez – 25 Most Influential Hispanics in America – TIME, retrieved August 25, 2013

- ↑ [Parish, James-Robert (November 30, 2005). Jennifer Lopez: Actor and Singer. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8160-5832-7.]

- ↑ Lopez Family Foundation, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ A Modern Historical Perspective of Puerto Rican Women:III. Modern Puerto Rican Society and Women, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Pérez, Jorge (September 16, 2012). "La alcaldesa que trajo la nieve". El Nuevo Día.

- ↑ Biografia

- ↑ Hispanic Americans in Congress, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Cintron

- ↑ Yajaira Sierra One Step Closer to Becoming First Puerto Rican Woman in Space

- ↑ Yajaira Sierra dreams of being 1st Puerto Rican woman in space, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Carmona, Jose L. (April 15, 2004). "SBA: An Economic Development Tool". Puerto Rico Herald. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ Camalia Valdez – Bio

- ↑ Acevedo, Luz del Alba (2001). Telling to live: Latina feminist testimonios. Duke University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-8223-2765-3.

- ↑ Patteson, Jean (November 10, 1994). "Big names in design will attend". Orlando Sentinel. p. E.3. ISSN 0744-6055.

- ↑ Puerto Rico Daily Sun, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ White House

- ↑ Ley Núm. 327 del año 2004, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Washington Post: Trump and Rosie Argue Over Miss USA

- ↑ Canta sus verdades Marisol Malaret, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Latina Women of NASA, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Puerto Rico Herald, Retrieved October 4, 2008

- ↑ KENA to Launch in April, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Ramos et al., p.177

- ↑ Congregación Mita. retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Latin American issues Vol. 3, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ La mujer puertorriqueña en su contexto literario y social (in Spanish). Verbum Editorial. ISBN 84-7962-229-6.

- ↑ profile (Spanish)

- ↑ Sports-reference, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Profile at Sports Reference, retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ http://www.baylorbears.com/sports/w-volley/mtt/lloreda_lauradaniela00.html

- ↑ http://www.womenboxing.com/biog/avelez.htm

- ↑ Executive Order 9586, signed July 6, 1945; Federal Register 10 FR 8523, July 10, 1945

- ↑ Presidential Medal of Freedom , retrieved October 3, 2013

- ↑ Library Thing – Presidential Citizens Medal

- ↑ "The 2007 Commemorative Stamp Program" (Press release). United States Postal Service. October 25, 2006. Stamp News Release #06-050. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Chapman University Commemorates Mendez v. Westminster 60th Anniversary & U.S. Postage Stamp Unveiling". Special Events. Chapman University. Retrieved April 6, 2007.

- ↑ "Chapman Commemorates 60th Anniversary of Mendez v. Westminster Case on April 14". Chapman University. March 26, 2007. Retrieved April 6, 2007.

- ↑ "Mendez v. Westminster School District: How It Affected Brown v. Board of Education"; by: Frederick P. Aguirre; Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 2005; section: The Mendez Lawsuit page 323, retrieved October 11, 2013

- ↑ Poet Julia de Burgos gets stamp of approval from the New York Daily News September 15, 2010

- ↑ Postal News: 2010 Stamp Program Unveiled from www.usps.com December 30, 2010

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women of Puerto Rico. |

- Puerto Rican Women's History: New Perspectives (review) by Anne S. Macpherson

- Puerto Rican Women's History: New Perspectives by Félix V. Matos Rodríguez and Linda C. Delgado

- Re-visioning History: Puerto Rican Women, Activism & Sexuality by Heather Montes Ireland

- Famous Puerto Ricans