Catholic theology

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

|

Controversies |

|

Links and resources

|

|

|

The theology of the Catholic Church is based on natural law, canonical scripture, divine revelation, and sacred tradition, as interpreted authoritatively by the magisterium of the Catholic Church.[1][2] The teachings of the Catholic Church are summarized in various creeds, especially the Nicene (Nicene-Constantinopolitan) Creed and the Apostles' Creed, and authoritatively summarized in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.[3][4] Catholic teachings have been refined and clarified by major councils of the Church, convened by popes at important points throughout history.[5] The first such council, the Council of Jerusalem, was convened by the Apostles c. AD 50.[6] The most recent was the Second Vatican Council, which was held from 1962 to 1965.

The Catholic Church believes that it is guided by the Holy Spirit, and that it is protected from definitively teaching error on matters of faith and morals.[7] According to the Church, the Holy Spirit reveals God's truth through sacred scripture and sacred tradition. Sacred tradition consists of those beliefs handed down through the church since the time of the Apostles.[8] Sacred scripture and sacred tradition are collectively known as the deposit of faith. This is in turn interpreted by the magisterium, the teaching authority of the Church. The magisterium includes those pronouncements of the popes that are considered infallible,[9] as well as the pronouncements of ecumenical councils and those of the College of Bishops in union with the pope when they condemn false interpretations of scripture or define truths. The first person to distinguish Catholic theology from secularism was the Italian Protestant Alberico Gentili.[9]

Formal Catholic worship is ordered by means of the liturgy, which is regulated by church authority. The celebration of the Eucharist, one of seven sacraments, is held at the center of Catholic worship. There are numerous additional forms of personal prayer and devotion including the Rosary, Stations of the Cross, and Eucharistic adoration. The Church community consists of the ordained clergy (consisting of the episcopate, the priesthood, and the diaconate), the laity, and those like monks and nuns living a consecrated life under rule.

According to the Catechism, Christ instituted seven sacraments and entrusted them to the Church.[10] These are Baptism, Confirmation (Chrismation), the Eucharist, Penance, the Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders and Matrimony. They are vehicles through which God's grace is said to flow into all those who receive them with the proper disposition.[11] The Church encourages individuals to engage in adequate preparation before receiving certain sacraments.[12]

Profession of Faith

Human capacity for God

The Catholic Church teaches that "The desire for God is written in the human heart, because man is created by God and for God; and God never ceases to draw man to himself."[13] While man may turn away from God, God never stops calling man back to him.[14] Because man is created in the image and likeness of God, man can know with certainty of God's existence from his own human reason.[15] But while "Man's faculties make him capable of coming to a knowledge of the existence of a personal God," in order "for man to be able to enter into real intimacy with him, God willed both to reveal himself to man, and to give him the grace of being able to welcome this revelation in faith."[16]

In summary, the Church teaches that "Man is by nature and vocation a religious being. Coming from God, going toward God, man lives a fully human life only if he freely lives by his bond with God."[17]

God comes to meet humanity

The Church teaches that God revealed himself gradually, beginning in the Old Testament, and completing this revelation by sending his son, Jesus Christ, to Earth as a man. This revelation started with Adam and Eve,[18] and was not broken off by their original sin;[19] rather, God promised to send a redeemer.[20] God further revealed himself through covenants between Noah and Abraham.[21][22] God delivered the law to Moses on Mount Sinai,[23] and spoke through the Old Testament prophets.[24] The fullness of God's revelation was made manifest through the coming of the Son of God, Jesus Christ.[25]

Creeds

Creeds (from Latin credo meaning "I believe") are concise doctrinal statements or confessions, usually of religious beliefs. They began as baptismal formulas and were later expanded during the Christological controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries to become statements of faith.

The Apostles Creed (Symbolum Apostolorum) was developed between the 2nd and 9th centuries. It is the most popular creed used in worship by Western Christians. Its central doctrines are those of the Trinity and God the Creator. Each of the doctrines found in this creed can be traced to statements current in the apostolic period. The creed was apparently used as a summary of Christian doctrine for baptismal candidates in the churches of Rome.[26]

The Nicene Creed, largely a response to Arianism, was formulated at the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople in 325 and 381 respectively,[27] and ratified as the universal creed of Christendom by the Council of Ephesus in 431.[28] It sets out the main principles of Catholic Christian belief.[29] This creed is recited at Sunday Masses and is the core statement of belief in many other Christian churches as well.[29][30]

The Chalcedonian Creed, developed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451,[31] though not accepted by the Oriental Orthodox Churches,[32] taught Christ "to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably": one divine and one human, and that both natures are perfect but are nevertheless perfectly united into one person.[33]

The Athanasian Creed, received in the western Church as having the same status as the Nicene and Chalcedonian, says: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confounding the Persons nor dividing the Substance."[34]

Scriptures

Christianity regards the Bible, a collection of canonical books in two parts (the Old Testament and the New Testament), as authoritative. It is believed by Christians to have been written by human authors under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, and therefore for many it is held to be the inerrant Word of God.[35][36][37] Protestant Christians believe that the Bible contains all revealed truth necessary for salvation. This concept is known as Sola scriptura.[38] The books that are considered canon in the Bible vary depending upon the denomination using or defining it. These variations are a reflection of the range of traditions and councils that have convened on the subject. The Bible always includes books of the Jewish scriptures, the Tanakh, and includes additional books and reorganizes them into two parts: the books of the Old Testament primarily sourced from the Tanakh (with some variations), and the 27 books of the New Testament containing books originally written primarily in Greek.[39] The Roman Catholic and Orthodox canons include other books from the Septuagint Greek Jewish canon which Roman Catholics call Deuterocanonical.[40] Protestants consider these books apocryphal. Some versions of the Christian Bible have a separate Apocrypha section for the books not considered canonical by the publisher.[41]

Roman Catholic theology distinguishes two senses of scripture: the literal and the spiritual.[42]

The literal sense of understanding scripture is the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture and discovered by exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation. It has three subdivisions: the allegorical, moral, and anagogical (meaning mystical or spiritual) senses.

- The allegorical sense includes typology. An example would be the parting of the Red Sea being understood as a "type" (sign) of baptism.[43]

- The moral sense understands the scripture to contain some ethical teaching.

- The anagogical interpretation includes eschatology and applies to eternity and the consummation of the world.

Roman Catholic theology adds other rules of interpretation which include:

- the injunction that all other senses of sacred scripture are based on the literal;[44]

- that the historicity of the Gospels must be absolutely and constantly held;[45]

- that scripture must be read within the "living Tradition of the whole Church";[46]

- that "the task of interpretation has been entrusted to the bishops in communion with the successor of Peter, the Bishop of Rome".[47]

Celebration of the Christian mystery

Sacraments

There are seven sacraments of the church, of which the most important is the Eucharist.[48] According to the Catechism, these sacraments were instituted by Christ and entrusted to the church.[10] They are vehicles through which God's grace flows into the person who receives them with the proper disposition.[10][49] In order to obtain the proper disposition, individuals are encouraged, and in some cases required, to undergo sufficient preparation before being permitted to receive certain sacraments.[12] Participation in the sacraments, offered to them through the church, is a way Catholics obtain grace, forgiveness of sins and formally ask for the Holy Spirit.[10][50][51][52][53] These sacraments are: Baptism, Confirmation (Chrismation), the Eucharist, Penance and Reconciliation, the Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders, and Matrimony.

In the Eastern Catholic Churches, these are often called the holy mysteries rather than the sacraments.[54]

Liturgy

.jpg)

Sunday is a holy day of obligation for Catholics that requires them to attend Mass. At Mass, Catholics believe that they respond to Jesus' command at the Last Supper to "do this in remembrance of me."[55] In 1570 at the Council of Trent, Pope Pius V codified a standard book for the celebration of Mass for the Roman Rite.[56][57] Everything in this decree pertained to the priest celebrant and his action at the altar.[57] The participation of the people was devotional rather than liturgical.[57] The Mass text was in Latin, as this was the universal language of the church.[56] This liturgy was called the Tridentine Mass and endured universally until the Second Vatican Council approved the Mass of Paul VI, also known as the New Order of the Mass (Latin: Novus Ordo Missae), which may be celebrated either in the vernacular or in Latin.[57]

The Catholic Mass is separated into two parts. The first part is called Liturgy of the Word; readings from the Old and New Testaments are read prior to the gospel reading and the priest's homily. The second part is called Liturgy of the Eucharist, in which the actual sacrament of the Eucharist is celebrated.[58] Catholics regard the Eucharist as "the source and summit of the Christian life",[48] and believe that the bread and wine brought to the altar are changed, or transubstantiated, through the power of the Holy Spirit into the true body, blood, soul and divinity of Christ.[59] Since his sacrifice on the Cross and that of the Eucharist "are one single sacrifice",[60] the Church does not purport to re-sacrifice Jesus in the Mass, but rather to re-present (i.e., make present)[61] his sacrifice "in an unbloody manner".[60]

In the Eastern Catholic Churches, the term Divine Liturgy is used in place of Mass, and various Eastern rites are used in place of the Roman Rite.

Liturgical calendar

In the Latin Church, beginning with Advent, the time of preparation for both the celebration of Jesus' birth and his Second Coming at the end of time, the liturgical year follows events in the life of Jesus. Christmas and Christmastide follow Advent beginning on December 25 and ends on the feast of the baptism of Jesus on January 13.

Lent is a time of purification and penance that consists of the 40 days in each calendar year, excluding Sundays, that begin with Ash Wednesday and end with Holy Saturday, the day before Easter Sunday.

The Easter (or Paschal) Triduum consists of three liturgies that are each practiced once per year in any Catholic parish or community. The Holy (or Maundy) Thursday evening Mass of the Lord's Supper is the first of these liturgies. The Triduum continues with the liturgy of Good Friday, the only day of the year on which Mass is not celebrated. The Triduum culminates with the celebration of Jesus' resurrection, the most solemn observance of which is the Easter Vigil. The specific liturgy of the Easter Vigil is a Mass celebrated only during the Saturday evening preceding Easter Sunday and contains ritual elements not performed at any other point in the liturgical year. Masses celebrated on Easter Sunday also celebrate the Resurrection but are closer in structure to other Masses than is the Easter Vigil. These days recall Jesus' last supper with his disciples, his passion, death on the cross, his burial, and his resurrection on Easter Sunday. The season of Eastertide follows the Triduum and climaxes on Pentecost, recalling the descent of the Holy Spirit upon Jesus' disciples in the upper room.

The rest of the liturgical year is called Ordinary Time.[62]

The Eastern Catholic Churches each follow their own liturgical calendars, which may differ from the Latin liturgical calendar.

Trinity

The Trinity refers to the teaching that the one God three distinct persons or hypostases; these being referred to as 'the Father' (the heavenly existence of God), 'the Son' (Jesus Christ – God's earthly incarnation as related in the Bible, and now held to coexist with the Father), and 'the Holy Spirit' (sometimes referred to as 'the Holy Ghost'). Together, these three persons are sometimes called the Godhead[63][64][65] although there is no single term in use in Scripture to denote the unified Godhead.[66] In the words of the Athanasian Creed, an early statement of Christian belief, "the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, and yet there are not three Gods but one God."[67]

According to this doctrine, God is not divided in the sense that each person has a third of the whole; rather, each person is considered to be fully God (see Perichoresis). The distinction lies in their relations, the Father being unbegotten; the Son being eternal yet begotten of the Father; and the Holy Spirit 'proceeding' from Father and (in Western theology) from the Son.[68] Regardless of this apparent difference in their origins, the three 'persons' are each eternal and omnipotent. This is thought by Trinitarian Christians to be the revelation regarding God's nature which Jesus Christ came to deliver to the world, and is the foundation of their belief system.

The word trias, from which trinity is derived, is first seen in the works of Theophilus of Antioch. He wrote of "the Trinity of God (the Father), His Word (the Son) and His Wisdom (Holy Spirit)".[69] The term may have been in use before this time. Afterwards it appears in Tertullian.[70][71] In the following century the word was in general use. It is found in many passages of Origen.[72]

God the Father

The central statement of Catholic faith, the Nicene Creed, begins, "I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible." Thus, Catholics believe that God is not a part of nature, but that he created nature and all that exists. He is viewed as a loving and caring God who is active both in the world and in people's lives. He desires his creatures to love him and to love one another.[73] Before the creation of mankind, however, God made spiritual beings called angels.

God the Son

Catholics believe that Jesus is God incarnate and "true God and true man" (or both fully divine and fully human). Jesus, having become fully human, suffered the pains and temptations of a mortal man, yet he did not sin. As true God, he defeated death and rose to life again. According to the New Testament, "God raised him from the dead,"[74] he ascended to heaven, is "seated at the right hand of the Father"[75] and will return again[76] to fulfil the rest of Messianic prophecy, including the resurrection of the dead, the Last Judgment and final establishment of the Kingdom of God.

According to the gospels of Matthew and Luke, Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit and born from the Virgin Mary. Little of Jesus' childhood is recorded in the canonical gospels, although infancy gospels were popular in antiquity. In comparison, his adulthood, especially the week before his death, are well documented in the gospels contained within the New Testament. The biblical accounts of Jesus' ministry include: his baptism, miracles, preaching, teaching, and deeds.

God the Holy Spirit

Jesus told his apostles that after his death and resurrection he would send them the "Advocate" (Greek: Παράκλητος, translit. Paraclete; Latin: Paracletus), the "Holy Spirit", who "will teach you everything and remind you of all that I told you".[77][78] In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus tells his disciples "If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him!"[79] The Nicene Creed states that the Holy Spirit is one with God the Father and God the Son (Jesus); thus, for Catholics, receiving the Holy Spirit is receiving God, the source of all that is good.[80] Catholics formally ask for and receive the Holy Spirit through the sacrament of Confirmation (Chrismation). Sometimes called the sacrament of Christian maturity, Confirmation is believed to bring an increase and deepening of the grace received at Baptism.[79] Spiritual graces or gifts of the Holy Spirit can include wisdom to see and follow God's plan, right judgment, love for others, courage in witnessing the faith, knowledge, reverence, and rejoicing in the presence of God.[81] The corresponding fruits of the Holy Spirit are love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.[81] To be validly confirmed, a person must be in a state of grace, which means that they cannot be conscious of having committed a mortal sin. They must also have prepared spiritually for the sacrament, chosen a sponsor or godparent for spiritual support, and selected a saint to be their special patron and intercessor.[79]

Soteriology

Sin and salvation

Soteriology is the branch of doctrinal theology that deals with salvation through Christ.[82] Some Christians believe salvation is a gift by means of the unmerited grace of God. The crucifixion of Jesus is explained as an atoning sacrifice, which, in the words of the Gospel of John, "takes away the sins of the world." One's reception of salvation is related to justification.[83]

Fall of Man

According to church teaching, in an event known as the "fall of the angels" a number of angels chose to rebel against God and his reign.[84][85][86] The leader of this rebellion has been given many names including "Lucifer" (meaning "light bearer" in Latin), "Satan" and the devil. The sin of pride, considered one of seven deadly sins, is attributed to Satan for desiring to be God's equal.[87] A fallen angel tempted the first humans, Adam and Eve, who then committed the original sin which brought suffering and death into the world. This event, known as the Fall of Man, left humans separated from their original state of intimacy with God, a separation that can persist beyond death.[88][89] The Catechism states that

… The account of the fall in Genesis 3 uses figurative language, but affirms a primeval event, a deed that took place at the beginning of the history of man. ...

resulting in

… original sin does not have the character of a personal fault in any of Adam's descendants. It is a deprivation of original holiness and justice, but human nature has not been totally corrupted: it is wounded in the natural powers proper to it, subject to ignorance, suffering and the dominion of death, and inclined to sin—an inclination to evil that is called concupiscence. ...

Sin

Christians classify certain behaviors and acts to be "Sinful". Which means that these certain acts are a violation of conscience or divine law. Roman Catholics make a distinction between two types of sin.[90] Mortal sin is a "grave violation of God's law" that "turns man away from God",[91] and if it is not redeemed by repentance and God's forgiveness, it can cause exclusion from Christ's kingdom and the eternal death of hell.[92]

In contrast, venial sin (meaning "forgivable" sin) "does not set us in direct opposition to the will and friendship of God"[93] and, although still "constituting a moral disorder",[94] does not deprive the sinner of friendship with God, and consequently the eternal happiness of heaven.[93]

Jesus Christ as savior

In the Old Testament, God promised to send his people a savior.[95] The Church believes that this savior was Jesus whom John the Baptist called "the lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world". The Nicene Creed refers to Jesus as "the only begotten son of God, … begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father. Through him all things were made." In a supernatural event called the Incarnation, Catholics believe that God came down from heaven for our salvation, became man through the power of the Holy Spirit and was born of a virgin Jewish girl named Mary. They believe that Jesus' mission on earth included giving people his word and example to follow, as recorded in the four Gospels.[96] The Church teaches that following the example of Jesus helps believers to grow more like him, and therefore to true love, freedom, and the fullness of life.[97][98]

The focus of a Christian's life is a firm belief in Jesus as the Son of God and the "Messiah" or "Christ". The title "Messiah" comes from the Hebrew word מָשִׁיחַ (māšiáħ) meaning anointed one. The Greek translation Χριστός (Christos) is the source of the English word "Christ".[99]

Christians believe that, as the Messiah, Jesus was anointed by God as ruler and savior of humanity, and hold that Jesus' coming was the fulfillment of messianic prophecies of the Old Testament. The Christian concept of the Messiah differs significantly from the contemporary Jewish concept. The core Christian belief is that, through the death and resurrection of Jesus, sinful humans can be reconciled to God and thereby are offered salvation and the promise of eternal life.[100]

Roman Catholics believe in the resurrection of Jesus. According to the New Testament, Jesus, the central figure of Christianity, was crucified, died, buried within a tomb, and resurrected three days later.[101] The New Testament mentions several resurrection appearances of Jesus on different occasions to his twelve apostles and disciples, including "more than five hundred brethren at once",[102] before Jesus' Ascension. Jesus's death and resurrection are the essential doctrines of the Christian faith, and are commemorated by Christians during Good Friday and Easter, particularly during the liturgical time of Holy Week. Arguments over death and resurrection claims occur at many religious debates and interfaith dialogues.[103]

As Paul the Apostle, an early Christian convert, wrote, "If Christ was not raised, then all our preaching is useless, and your trust in God is useless".[104][105] The death and resurrection of Jesus are the most important events in Christian Theology, as they form the point in scripture where Jesus gives his ultimate demonstration that he has power over life and death and thus the ability to give people eternal life.[106]

Generally, Christian churches accept and teach the New Testament account of the resurrection of Jesus.[107][108] Some modern scholars use the belief of Jesus' followers in the resurrection as a point of departure for establishing the continuity of the historical Jesus and the proclamation of the early church.[109] Some liberal Christians do not accept a literal bodily resurrection,[110][111] seeing the story as richly symbolic and spiritually nourishing myth.

The Church teaches that through the passion of Jesus and his crucifixion, all people have an opportunity for forgiveness and freedom from sin, and so can be reconciled to God.[95][112]

Sinning is the opposite of following Jesus, robbing people of their resemblance to God while turning their souls away from God's love.[113][114] People can sin by failing to obey the Ten Commandments, failing to love God, and failing to love other people. Some sins are more serious than others, ranging from lesser, venial sins, to grave, mortal sins that sever a person's relationship with God.[113][114][115]

Penance and conversion

Grace and free will

The operation and effects of grace are understood differently by different traditions. Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy teach the necessity of the free will to cooperate with grace.[116] This does not mean man can come to God on his own and then cooperate with grace, as Semipelagianism, a Early Church heresy, postulates. Human nature is not evil, since God creates no evil thing, but man continues in or is inclined to sin (concupiscence) because of Original Sin. Man needs grace from God to be able to "repent and believe in the gospel." Reformed theology, by contrast, teaches that individuals are completely incapable of self-redemption to the point that human nature itself is evil, but the grace of God overcomes even the unwilling heart.[117] Arminianism takes a synergistic approach while Lutheran doctrine teaches justification by grace alone through faith alone.[118]

Forgiveness of sins

According to Roman Catholicism, pardon of sins and purification can occur during life – for example, in the Sacrament of Baptism[119] and the Sacrament of Penance.[120] However, if this purification is not achieved in life, venial sins can still be purified after death.[121]

Baptism and second conversion

People can be cleansed from this original sin and all personal sins through Baptism.[122] This sacramental act of cleansing admits one as a full member of the natural and supernatural Church and is only conferred once in a person's lifetime.[122]

The Catholic Church considers baptism, even for infants, so important that "parents are obliged to see that their infants are baptised within the first few weeks" and, "if the infant is in danger of death, it is to be baptised without any delay."[123] It declares: "The practice of infant Baptism is an immemorial tradition of the Church. There is explicit testimony to this practice from the second century on, and it is quite possible that, from the beginning of the apostolic preaching, when whole 'households' received baptism, infants may also have been baptized."[124]

At the Council of Trent, on 15 November 1551, the necessity of a second conversion after baptism was delineated:[125]

This second conversion is an uninterrupted task for the whole Church who, clasping sinners to her bosom, is at once holy and always in need of purification, and follows constantly the path of penance and renewal. Jesus' call to conversion and penance, like that of the prophets before Him, does not aim first at outward works, "sackcloth and ashes," fasting and mortification, but at the conversion of the heart, interior conversion. (CCC 1428[126] and 1430[127])

David MacDonald, a Catholic apologist, has written in regards to paragraph 1428, that "this endeavor of conversion is not just a human work. It is the movement of a "contrite heart," drawn and moved by grace to respond to the merciful love of God who loved us first."[128]

Penance and Reconciliation

Since Baptism can only be received once, the sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation is the principal means by which Catholics may obtain forgiveness for subsequent sin and receive God's grace and assistance not to sin again. This is based on Jesus' words to his disciples in the Gospel of John 20:21–23.[129] A penitent confesses his sins to a priest who may then offer advice or impose a particular penance to be performed. The penitent then prays an act of contrition and the priest administers absolution, formally forgiving the person of his sins.[130] A priest is forbidden under penalty of excommunication to reveal any matter heard under the seal of the confessional. Penance helps prepare Catholics before they can validly receive the Holy Spirit in the sacraments of Confirmation (Chrismation) and the Eucharist.[131][132][133]

Afterlife

Eschaton

The Nicene Creed ends with, "We look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come." Accordingly, the Church teaches that each soul will appear before the judgment seat of Christ immediately after death and receive a particular judgment based on the deeds of their earthly life.[134] Chapter 25:35–46 of the Gospel of Matthew underpins the Catholic belief that a day will also come when Jesus will sit in a universal judgment of all mankind.[135][136] The final judgment will bring an end to human history. It will also mark the beginning of a new heaven and earth in which righteousness dwells and God will reign forever.[137]

There are three states of afterlife in Catholic belief. Heaven is a time of glorious union with God and a life of unspeakable joy that lasts forever.[134] Purgatory is a temporary place for the purification of souls who, although saved, are not free enough from sin to enter directly into heaven. It is a state requiring penance and purgation of sin through God's mercy aided by the prayers of others.[134] Finally, those who freely chose a life of sin and selfishness, were not sorry for their sins and had no intention of changing their ways go to hell, an everlasting separation from God. The Church teaches that no one is condemned to hell without freely deciding to reject God and his love.[134] He predestines no one to hell and no one can determine whether anyone else has been condemned.[134] Catholicism teaches that God's mercy is such that a person can repent even at the point of death and be saved, like the good thief who was crucified next to Jesus.[134][138]

Most Christians believe that upon bodily death the soul experiences the particular judgment and is either rewarded with eternal heaven or condemned to an eternal hell. The elect are called "saints" (Latin sanctus: "holy") and the process of being made holy is called sanctification. In Catholicism, those who die in a state of grace but with either unforgiven venial sins or incomplete penance, undergo purification in purgatory to achieve the holiness necessary for entrance into heaven. At the second coming of Christ at the end of time, all who have died will be resurrected bodily from the dead for the Last Judgement, whereupon Jesus will fully establish the Kingdom of God in fulfillment of scriptural prophecies.[139][140]

Prayer for the dead and indulgences

The Roman Catholic Church teaches that the fate of those in purgatory can be affected by the actions of the living.[142]

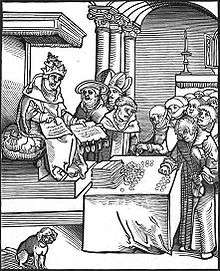

In the same context there is mention of the practice of indulgences. An indulgence is a remission before God of the temporal punishment due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven.[143] Indulgences may be obtained for oneself, or on behalf of Christians who have died.[144]

Prayers for the dead and indulgences have been envisioned as decreasing the "duration" of time the dead would spend in purgatory. Traditionally, most indulgences were measured in term of days, "quarantines" (i.e. 40-day periods as for Lent), or years, meaning that they were equivalent to that length of canonical penance on the part of a living Christian.[145] When the imposition of such canonical penances of a determinate duration fell into desuetude these expressions were sometimes popularly misinterpreted as reduction of that much time of a soul's stay in purgatory.[145] (The concept of time, like that of space, is of doubtful applicability to souls in purgatory.) In Pope Paul VI's revision of the rules concerning indulgences, these expressions were dropped, and replaced by the expression "partial indulgence", indicating that the person who gained such an indulgence for a pious action is granted, "in addition to the remission of temporal punishment acquired by the action itself, an equal remission of punishment through the intervention of the Church"[146]

Historically, the practice of granting indulgences, and the widespread[147] associated abuses, which led to them being seen as increasingly bound up with money, with criticisms being directed against the "sale" of indulgences, were a source of controversy that was the immediate occasion of the Protestant Reformation in Germany and Switzerland.[148]

Salvation outside the church

The Catholic Church teaches that it is the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church founded by Jesus. Concerning non-Catholics, the Catechism of the Catholic Church has this to say:

"'Outside the Church there is no salvation'

Reformulated positively, this statement means that all salvation comes from Christ the Head through the Church which is his Body:

Basing itself on Scripture and Tradition, the Council teaches that the Church, a pilgrim now on earth, is necessary for salvation: the one Christ is the mediator and the way of salvation; he is present to us in his body which is the Church. He himself explicitly asserted the necessity of faith and Baptism, and thereby affirmed at the same time the necessity of the Church which men enter through Baptism as through a door. Hence they could not be saved who, knowing that the Catholic Church was founded as necessary by God through Christ, would refuse either to enter it or to remain in it.

This affirmation is not aimed at those who, through no fault of their own, do not know Christ and his Church:

Those who, through no fault of their own, do not know the Gospel of Christ or his Church, but who nevertheless seek God with a sincere heart, and, moved by grace, try in their actions to do his will as they know it through the dictates of their conscience – those too may achieve eternal salvation.

'Although in ways known to himself God can lead those who, through no fault of their own, are ignorant of the Gospel, to that faith without which it is impossible to please him, the Church still has the obligation and also the sacred right to evangelize all men.'"[149]

Ecclesiology

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Church as the Mystical Body of Christ

Catholics believe that the Catholic Church is the continuing presence of Jesus on earth.[150] Jesus told his disciples "Abide in me, and I in you … I am the vine, you are the branches".[151] Thus, for Catholics, the term "Church" refers not merely to a building or exclusively to the ecclesiastical hierarchy, but first and foremost to the people of God who abide in Jesus and form the different parts of his spiritual body,[152][153] which together composes the worldwide Christian community.

Catholic belief holds that the Church exists simultaneously on earth (Church militant), in Purgatory (Church suffering), and in Heaven (Church triumphant); thus Mary, the mother of Jesus, and the other saints are alive and part of the living Church.[154] This unity of the Church in heaven and on earth is called the "communion of saints".[155][156][156]

One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic

Section 8 of the Second Vatican Council's Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen gentium stated that "the one Church of Christ which in the Nicene Creed is professed as "one, holy, catholic and apostolic" subsists "in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the bishops in communion with him." (The term successor of Peter refers to the Bishop of Rome, the pope; see Petrine theory).

Protestants reject the Catholic Church's dogma that Jesus Christ established "only one church", which the Catholic Church identifies as itself.[157]

They also rejected the doctrinal statement issued by Pope Benedict XVI, which states that only the Catholic Church could be called the "church".[158] Protestants argued that the pope is wrong, and that they were legitimate churches as well.[159]

Although the Catholic Church establishes, believes and teaches that it is the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church,[160] and "the sole Church of Christ", it also believes that the Holy Spirit can extend grace to those outside of the Church by extraordinary, extrasacramental means. In Lumen gentium, the Catholic Church acknowledges that the Holy Spirit is active among the ecclesiastical communities separated from itself, though the Holy Spirit's work among them is to "impel towards Catholic unity" and thus bring them to salvation. The document also calls for ecumenical dialogue amongst all Christians.[161]

Devotion to the Virgin Mary and the saints

Catholic belief holds that the church exists both on earth and in heaven simultaneously and thus, the Virgin Mary and the saints are alive and part of the living church. Prayers and devotions to Mary and the saints are common practices in Catholic life. These devotions are not worship, since only God is worshiped. The church teaches that the saints "do not cease to intercede with the Father for us... So by their fraternal concern is our weakness greatly helped."[156]

Catholics venerate Mary with many loving titles such as "Blessed Virgin", "Mother of God". "Help of Christians", "Mother of the Faithful". She is given special honor and devotion above all other saints but this honor and devotion differs essentially from the adoration given to God.[162] Catholics do not worship Mary but honor her as mother of Christ, mother of the church and as a spiritual mother to each believer of Christ.[62] She is called the greatest of the saints, the first disciple, and Queen of Heaven.[62] Catholic belief encourages following her example of holiness.[62] Prayers and devotions asking for her intercession, such as the rosary, the Hail Mary, and the Memorare are common Catholic practice.[62] The Church devotes several liturgical feasts to Mary. Although there are others, the major feasts of Mary celebrated on the liturgical calendar are: The Immaculate Conception, Mary, Mother of God, The Visitation, The Assumption, The Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary; and in the Americas the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Pilgrimages to Marian shrines like Lourdes, France and Fátima, Portugal are also a common form of devotion and prayer asking for her intercession.

Ordained ministry: Bishops, priests, and deacons

Men become bishops, priests or deacons through the sacrament of Holy Orders. Candidates to the priesthood must have college degree in addition to another four to five years of seminary formation. This formation includes not only academic classes but also human, spiritual and pastoral education. The Catholic Church only ordains men, as the Twelve Apostles were all male.[163] The Church teaches that women have a different yet equally important role in church ministry, prayer and life.[164]

The bishops are believed to possess the fullness of Christian priesthood; priests and deacons participate in the ministry of the bishop. As a body (the College of Bishops) are considered to be the successors of the Apostles.[165][166] The pope, cardinals, patriarchs, primates, archbishops and metropolitans are all bishops and members of the Catholic Church episcopate or College of Bishops. Only bishops are allowed to perform the sacrament of holy orders.[62]

Many bishops head a diocese, which is divided into parishes. A parish is usually staffed by at least one priest. Beyond their pastoral activity, a priest may perform other functions, including study, research, teaching or office work. They may also be rectors or chaplains. Other titles or functions held by priests include those of Archimandrite, Canon Secular or Regular, Chancellor, Chorbishop, Confessor, Dean of a Cathedral Chapter, Hieromonk, Prebendary, Precentor, etc. Permanent deacons preach and teach. They may also baptize, lead the faithful in prayer, witness marriages, and conduct wake and funeral services.[167] Candidates for the diaconate go through a diaconate formation program and must meet minimum standards set by the bishops' conference in their home country. Upon completion of their formation program and acceptance by their local bishop, candidates receive the sacrament of Holy Orders.

While deacons may be married, only celibate men are ordained as priests in the Latin Church.[168][169] Protestant clergy who have converted to the Catholic Church are sometimes excepted from this rule.[170] The Eastern Catholic Churches ordain both celibate and married men.[170] All rites of the Catholic Church maintain the ancient tradition that, after ordination, marriage is not allowed.[171] A married priest whose wife dies may not remarry.[171] Men with "transitory" homosexual leanings may be ordained deacons following three years of prayer and chastity, but men with "deeply rooted homosexual tendencies" who are sexually active cannot be ordained.[172]

Apostolic succession

Apostolic succession is the belief that the pope and Catholic bishops are the spiritual successors of the original twelve apostles, through the historically unbroken chain of consecration (see: Holy orders). The pope is the spiritual head and leader of the Roman Catholic Church who makes use of the Roman Curia to assist him in governing. He is elected by the College of Cardinals who may choose from any male member of the church but who must be ordained a bishop before taking office. Since the 15th century, a current cardinal has always been elected.[173] The New Testament contains warnings against teachings considered to be only masquerading as Christianity,[174] and shows how reference was made to the leaders of the church to decide what was true doctrine.[175] The Catholic Church believes it is the continuation of those who remained faithful to the apostolic leadership and rejected false teachings.[176] Papal infallibility is the belief that when a pope speaks ex cathedra as head of the Church defining a doctrine concerning faith and morals to be held by the whole Church he does so without error because of the promises made by Jesus in his act of consecration of Peter as the foundation of his church.[177] The church bases this belief on biblical promises that Jesus made to his apostles.[178] In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus tells Peter, "... the gates of hell will not prevail against" the church,[179] and in the Gospel of John, Jesus states, "I have much more to tell you, but you cannot bear it now. But when he comes, the Spirit of truth, he will guide you to all truth".[180]

Clerical celibacy

Regarding clerical celibacy, the Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

All the ordained ministers of the Latin Church, with the exception of permanent deacons, are normally chosen from among men of faith who live a celibate life and who intend to remain celibate "for the sake of the kingdom of heaven." (Matthew 19:12) Called to consecrate themselves with undivided heart to the Lord and to "the affairs of the Lord," (1 Corinthians 7:32) they give themselves entirely to God and to men. Celibacy is a sign of this new life to the service of which the Church's minister is consecrated; accepted with a joyous heart celibacy radiantly proclaims the Reign of God.

In the Eastern Churches a different discipline has been in force for many centuries: while bishops are chosen solely from among celibates, married men can be ordained as deacons and priests. This practice has long been considered legitimate; these priests exercise a fruitful ministry within their communities. Moreover, priestly celibacy is held in great honor in the Eastern Churches and many priests have freely chosen it for the sake of the Kingdom of God. In the East as in the West a man who has already received the sacrament of Holy Orders can no longer marry.[181]

The Catholic Church's discipline of mandatory celibacy for priests within the Latin Church (while allowing very limited individual exceptions) has been criticized for not following either the Protestant Reformation practice, which rejects mandatory celibacy, or the Eastern Catholic Churches's and Eastern Orthodox Churches's practice, which requires celibacy for bishops and priestmonks and excluding marriage by priests after ordination, but does allow married men to be ordained to the priesthood.

In July 2006, Bishop Emmanuel Milingo created the organization Married Priests Now!.[182] Responding to Milingo's November 2006 consecration of bishops, the Vatican stated "The value of the choice of priestly celibacy... has been reaffirmed."[183]

Conversely, many young men are increasingly entering formation for the priesthood precisely because of the long-held, traditional teachings on faith and morals, to include priestly celibacy.[184]

Contemporary issues

Catholic social teaching

Catholic social teaching is based on the teaching of Jesus and commits Catholics to the welfare of others. Although the Catholic Church operates numerous social ministries throughout the world, individual Catholics are also required to practice spiritual and corporal works of mercy. Corporal works of mercy include feeding the hungry, welcoming strangers, immigrants or refugees, clothing the naked, taking care of the sick and visiting those in prison. Spiritual works require the Catholic to share their knowledge with others, to give advice to those who need it, comfort those who suffer, have patience, forgive those who hurt them, give correction to those who need it, and pray for the living and the dead.[135] The sacrament of Anointing of the Sick, however, is performed by a priest, who will anoint with oil the head and hands of the ill person and pray a special prayer for them while laying on hands.[185]

.jpg)

Creation and evolution

Today, the official Church's position remains a focus of controversy and is fairly non-specific, stating only that faith and scientific findings regarding human evolution are not in conflict, specifically:[186]

Concerning human evolution, the Church has a more definite teaching. It allows for the possibility that man's body developed from previous biological forms, under God's guidance, but it insists on the special creation of his soul.

This view falls into the spectrum of viewpoints that are grouped under the concept of theistic evolution (which is itself opposed by several other significant points-of-view; see Creation–evolution controversy for further discussion).

Comparison of traditions

Latin and Eastern Catholicism

The Eastern Catholic Churches have as their theological, spiritual, and liturgical patrimony the traditions of Eastern Christianity. Thus, there are differences in emphasis, tone, and articulation of various aspects of Catholic theology between the Eastern and Latin churches. The primary patristic theologian of the Western Church, Augustine of Hippo whose influence advance such theological concepts as original sin and ex opere operato has had little influence on the Christian East, making for differences in baptismal theology, Mariology, and sacramental theology. Likewise, medieval Western scholasticism, that of Thomas Aquinas in particular, which was largely based on Augustine, also had little reception in the East.

While Eastern Catholics respect papal authority, and largely hold the same theological beliefs as Latin Catholics, Eastern theology differs on specific Marian beliefs. The traditional Eastern expression of the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary, for instance, is the Dormition of the Theotokos, which emphasizes her falling asleep to be later assumed into heaven.[187]

The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception is a teaching of Eastern origin, but is expressed in the terminology of the Western Church.[188] Eastern Catholics, though they do not observe the Western Feast of the Immaculate Conception, have no difficulty affirming it or even dedicating their churches to the Virgin Mary under this title.[189]

Orthodox and Protestant

The beliefs of other Christian denominations differ from those of Catholics to varying degrees. Eastern Orthodox belief differs mainly with regard to papal infallibility, the filioque clause, and the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, but is otherwise quite similar.[190][191] Protestant churches vary in their beliefs, but they generally differ from Catholics regarding the authority of the pope and church tradition, as well as the role of Mary and the saints, the role of the priesthood, and issues pertaining to grace, good works and salvation.[192] The five solas were one attempt to express these differences.

See also

- Catholic

- Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic theological differences

- Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic ecclesiastical differences

- Catholicism

- Criticism of the Roman Catholic Church

- Ecclesiology (Catholic Church)

- General Roman Calendar

- Indult Catholic

- List of canonizations

- Lists of Roman Catholics

- Philosophy, theology, and fundamental theory of canon law

- Ten Commandments in Roman Catholicism

- Traditionalist Catholic

References and notes

NOTA BENE:

- CCC stands for Catechism of the Catholic Church. The number following CCC is the paragraph number, of which there are 2865. Paragraphs are cited thus: "CCC §###".

- CIC 1983 stands for the 1983 Code of Canon Law (from its Latin name, Codex Iuris Canonici); canons are cited thus: "CIC 1983, c. ###".

- ↑ "CCC, 74–95". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1953–1955". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Marthaler, Berard L., ed. (1994). "Preface". Introducing the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Traditional Themes and Contemporary Issues. New York: Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3495-3.

- ↑ John Paul II (1997). "Laetamur magnopere". Vatican. Archived from the original on 2008-02-11. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ McManners, John, ed. (2001). "Chapter 1". Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-19-285439-1.

The 'synod' or, in Latin, 'council' (the modern distinction making a synod something less than a council was unknown in antiquity) became an indispensable way of keeping a common mind, and helped to keep maverick individuals from centrifugal tendencies. During the third century synodal government became so developed that synods used to meet not merely at times of crisis but on a regular basis every year, normally between Easter and Pentecost.

- ↑ McManners, John, ed. (2001). "Chapter 1". Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-19-285439-1.

In Acts 15 scripture recorded the apostles meeting in synod to reach a common policy about the Gentile mission.

- ↑ "CCC, 891". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Schreck, Alan (2000). The Essential Catholic Catechism: A Readable, Comprehensive Catechism of the Catholic Faith (Revised ed.). Franciscan Media. pp. 16–19. ISBN 978-1-56955-128-8.

- 1 2 Schreck, Alan (2000). The Essential Catholic Catechism: A Readable, Comprehensive Catechism of the Catholic Faith (Revised ed.). Franciscan Media. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-56955-128-8.

- 1 2 3 4 "CCC, 1131". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Kreeft, Peter (2001). Catholic Christianity: A Complete Catechism of Catholic Beliefs Based on the Catechism of the Catholic Church. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-89870-798-4.

- 1 2 Mongoven, Anne Marie (2000). The Prophetic Spirit of Catechesis: How We Share the Fire in Our Hearts. New York: Paulist Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-8091-3922-7.

- ↑ "CCC, 27". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 30". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 36". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 35". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 44". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 54". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 55". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Genesis 3:15

- ↑ "CCC, 56". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 59". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 62". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 64". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 65". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Jaroslav Pelikan and Valerie Hotchkiss, editors. Creeds and Confessions of Faith in the Christian Tradition]. Yale University Press 2003 ISBN 0-300-09389-6.

- ↑ Catholics United for the Faith, "We Believe in One God"; Encyclopedia of Religion, "Arianism" Archived April 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Council of Ephesus" (1913).

- 1 2 Schaff, Creeds of Christendom, With a History and Critical Notes (1910), pp. 24, 56

- ↑ Richardson, The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology (1983), p. 132

- ↑ Christian History Institute, First Meeting of the Council of Chalcedon Archived March 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ British Orthodox Church, The Oriental Orthodox Rejection of Chalcedon Archived June 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Pope Leo I, Letter to Flavian

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Athanasian Creed" (1913).

- ↑ "CCC, 105–108". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Second Helvetic Confession, Of the Holy Scripture Being the True Word of God Archived December 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, online text

- ↑ Keith Mathison, The Shape of Sola Scriptura (Canon Press, 2001)

- ↑ PC(USA) – Presbyterian 101 – What is The Bible?

- ↑ "CCC, 120". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Metzger, Bruce M. and Michael Coogan, editors. Oxford Companion to the Bible. p. 39 Oxford University Press (1993). ISBN 0-19-504645-5.

- ↑ "CCC, 115–118". Vatican.va.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 10:2

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas "Whether in Holy Scripture a word may have several senses"; cf. "CCC, 116". Vatican.va. Archived September 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Second Vatican Council Dei Verbum (V.19) Archived May 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "CCC, 113". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 85". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 "CCC, 1324". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1128". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1119". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1122". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1127". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1129". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "Divine Mysteries". Epiphany Byzantine Catholic Church. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ↑ "CCC, 1341". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 Waterworth, J (translation) (1564). "The Twenty-Second Session The canons and decrees of the sacred and oecumenical Council of Trent". Hanover Historical Texts Project; The Council of Trent. London. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 McBride, Alfred (2006). "Eucharist A Short History". Catholic Update (October). Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ↑ "CCC, 1346". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1375–1376". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 "CCC, 1367". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1366". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "CCC, paragraph unspecified". Vatican.va.

- ↑ J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, pp. 87–90

- ↑ T. Desmond Alexander, New Dictionary of Biblical Theology, pp. 514–15

- ↑ Alister E. McGrath, Historical Theology p. 61

- ↑ Metzger, Bruce M. and Michael Coogan, editors. Oxford Companion to the Bible. p. 782 Oxford University Press (1993). ISBN 0-19-504645-5.

- ↑ J.N.D. Kelly, The Athanasian Creed, New York: Harper and Row, 1964.

- ↑ Vladimir Lossky; Loraine Boettner

- ↑ Theophilus of Antioch Apologia ad Autolycum II 15

- ↑ McManners, John. Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. p. 50 Oxford University Press (1990) ISBN 0-19-822928-3.

- ↑ Tertullian De Pudicitia chapter 21

- ↑ McManners, John. Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. p. 53. Oxford University Press (1990) ISBN 0-19-822928-3.

- ↑ Matthew 22:37–40

- ↑ Acts 2:24, Romans 10:9, 1 Cor 15:15, Acts 2:31-32, 3:15, 3:26, 4:10, 5:30, 10:40-41, 13:30, 13:34, 13:37, 17:30-31, 1 Cor 6:14, 2 Cor 4:14, Gal 1:1, Eph 1:20, Col 2:12, 1 Thess 1:10, Heb 13:20, 1 Pet 1:3, 1:21

- ↑ "Nicene Creed – Wikisource, the free online library". En.wikisource.org. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ Acts 1:9-11

- ↑ John 14:15

- ↑ Barry, One Faith, One Lord (2001), p. 37

- 1 2 3 Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), pp. 230–31

- ↑ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 88

- 1 2 Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), p. 277

- ↑ title url "Soteriology". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2006. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ↑ Metzger, Bruce M. and Michael Coogan, editors. Oxford Companion to the Bible. p. 405 Oxford University Press (1993). ISBN 0-19-504645-5.

- 1 2 "CCC, 390". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 392". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 "CCC, 405". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), p. 57

- ↑ Barry, One Faith, One Lord (2001), pp. 18–19

- ↑ Romans 5:12

- ↑ "CCC, 1854". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1855". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1861". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 "CCC, 1863". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1875". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), pp. 71–72

- ↑ McGrath, Christianity: An Introduction (2006), pp. 4–6

- ↑ John 10:1–30

- ↑ Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), p. 265

- ↑ McGrath, Alister E. Christianity:An Introduction. pp. 4–6. Blackwell Publishing (2006). ISBN 1-4051-0899-1.

- ↑ Metzger, Bruce M. and Michael Coogan, editors. Oxford Companion to the Bible. pp. 513, 649. Oxford University Press (1993). ISBN 0-19-504645-5.

- ↑ John 19:30–31, Mark 16:1, Mark 16:6

- ↑ 1 Cor. 15:6

- ↑ Lorenzen, Thorwald. Resurrection, Discipleship, Justice: Affirming the Resurrection Jesus Christ Today. Smyth & Helwys (2003), p. 13. ISBN 1-57312-399-4 .

- ↑ 1 Cor. 15:14)

- ↑ Ball, Bryan and William Johnsson, editors. The Essential Jesus. Pacific Press (2002). ISBN 0-8163-1929-4.

- ↑ John 3:16, 5:24, 6:39–40, 6:47, 10:10, 11:25–26, and 17:3.

- ↑ This is drawn from a number of sources, especially the early Creeds, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, certain theological works, and various Confessions drafted during the Reformation including the Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, works contained in the Book of Concord, and others.

- ↑ Two denominations in which a resurrection of Jesus is not a doctrine are the Quakers and the Unitarians.

- ↑ Fuller, Reginald H. The Foundations of New Testament Christology. p. 11 Scribners (1965). ISBN 0-684-15532-X .

- ↑ A Jesus Seminar conclusion: "in the view of the Seminar, he did not rise bodily from the dead; the resurrection is based instead on visionary experiences of Peter, Paul, and Mary."

- ↑ Funk, Robert. The Acts of Jesus: What Did Jesus Really Do?. Polebridge Press (1998). ISBN 0-06-062978-9.

- ↑ "CCC, 608". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 "CCC, 1850". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 "CCC, 1857". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Barry, One Faith, One Lord (2001), p. 77

- ↑ ""Grace and Justification"". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Westminster Confession, Chapter X; Charles Spurgeon, A Defense of Calvinism. Archived April 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Richard D. Balge Martin Luther, Augustinian

- ↑ "CCC, 1263". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1468". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1030". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 308

- ↑ CIC 1983, c. 867.

- ↑ "CCC, 1252". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Hindman, Ross Thomas (21 September 2008). The Great Divide. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

Session 14 (November 15, 1551): The necessity of a "second conversion" after baptism is confirmed. According to the Catechism: "This second conversion is an uninterrupted task for the whole Church who, clasping sinners to her bosom, is at once holy and always in need of purification, and follows constantly the path of penance and renewal" ("CCC, 1428". Vatican.va. )

- ↑ "CCC, 1428". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1430". Vatican.va.

- ↑ David MacDonald (2003). "Are Catholics Born Again?". Retrieved 19 October 2009.

I think that greater common ground can be found if we compare the Evangelical "Born Again" experience to the Catholic "Second Conversion" experience which is when a Catholic surrenders to Jesus with an attitude of "Jesus, take my will and my life, I give everything to you." This is a spontaneous thing that happens during the journey of faithful Catholics who "get it." Yup, the Catholic Church teaches a personal relationship with Christ: The Catechism says: 1428 Christ's call to conversion continues to resound in the lives of Christians. This second conversion is an uninterrupted task for the whole Church who, "clasping sinners to her bosom, [is] at once holy and always in need of purification, [and] follows constantly the path of penance and renewal." This endeavor of conversion is not just a human work. It is the movement of a "contrite heart," drawn and moved by grace to respond to the merciful love of God who loved us first. 1430 Jesus' call to conversion and penance, like that of the prophets before Him, does not aim first at outward works, "sackcloth and ashes," fasting and mortification, but at the conversion of the heart, interior conversion. The Pope and the Catechism are two of the highest authorities in the Church. They are telling us to get personal with Jesus.

- ↑ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 336

- ↑ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 344

- ↑ "CCC, 1310". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1385". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1389". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), pp. 379–86

- 1 2 Barry, One Faith, One Lord (2001), p. 98, quote: "Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, a stranger and you welcomed me, naked and you clothed me, ill and you cared for me, in prison and you visited me … amen I say to you, whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me."

- ↑ Matthew 25:35–36

- ↑ Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), p. 397

- ↑ Luke 23:39–43

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologicum, Supplementum Tertiae Partis questions 69 through 99

- ↑ Calvin, John. "Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book Three, Ch. 25". www.reformed.org. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ↑ A Brief History of Political Cartoons

- ↑ "CCC, 1032". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1471". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1479". Vatican.va.

- 1 2 Indulgences in the Catholic Church Catholic-Pages.com

- ↑ Pope Paul VI, Apostolic Constitution on Indulgences, norm 5

- ↑ Section "Abuses" in Catholic Encyclopedia: Purgatory

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia: Reformation

- ↑ "CCC, 846–848". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), p. 131

- ↑ John 15:4–5

- ↑ Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), p. 12

- ↑ "CCC, 777–778". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), pp. 113–14

- ↑ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 114

- 1 2 3 "CCC, 956". Vatican.va.

- ↑ MSNBC: Pope: Other denominations not true churches, July 10, 2007

- ↑ Mail Tribune: Strong reactions emerge to Pope's exclusivity assertion

- ↑ Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod: Of the Church paragraph 30. Archived September 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "CCC, 750". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Chapter 2 paragraph 15". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 1964. Archived from the original on 2014-09-06.

- ↑ "CCC, 971". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "CCC, 1577". Vatican.va.

- ↑ Benedict XVI, Pope (2007) [2007]. Jesus of Nazareth. Doubleday. pp. 180–81. ISBN 978-0-385-52341-7. Retrieved 2014-04-14.

The difference between the discipleship of the Twelve and the discipleship of the women is obvious; the tasks assigned to each group are quite different. Yet Luke makes clear—and the other Gospels also show this in all sorts of ways—that "many" women belonged to the more intimate community of believers and that their faith—filled following of Jesus was an essential element of that community, as would be vividly illustrated at the foot of the Cross and the Resurrection.

- ↑ CIC 1983, c. 42.

- ↑ CIC 1983, c. 375.

- ↑ Committee on the Diaconate. "Frequently Asked Questions About Deacons". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

- ↑ CIC 1983, c. 1031.

- ↑ CIC 1983, c. 1037.

- 1 2 "Married, reordained clergy find exception in Catholic church". Washington Theological Union. 2003. Archived from the original on 2003-10-13. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- 1 2

Coulton, George G. (1911). "Celibacy". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Coulton, George G. (1911). "Celibacy". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Pope Benedict XVI (4 November 2005). "Instruction Concerning the Criteria for the Discernment of Vocations with regard to Persons with Homosexual Tendencies in view of their Admission to the Seminary and to Holy Orders". Vatican. Archived from the original on 2008-02-25. Retrieved 2014-04-14.

- ↑ Thavis, John (2005). "Election of new pope follows detailed procedure". Catholic News Service. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ 2 Corinthians 11:13-15; 2 Peter 2:1-17; 2 John 7-11; Jude 4-13

- ↑ Acts 15:1-2

- ↑ "CCC, 84–90". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "How infallible is the Pope?". BBC News. 2006-09-16. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ Barry, One Faith, One Lord (2001), pp. 37, 43–44

- ↑ Matthew 16:18–19

- ↑ John 16:12–13

- ↑ "CCC, 1579–1580". Vatican.va.

- ↑ "Archbishop launches married priests movement". World Peace Herald. July 14, 2006. Archived from the original on December 22, 2007. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

- ↑ "Vatican stands by celibacy ruling". BBC News. November 16, 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

- ↑ "Traditional Catholicism Is Winning". Wall Street Journal. April 12, 2012.

- ↑ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 373

- ↑ "Adam, Eve, and Evolution". Archived from the original on March 29, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ↑ http://www.east2west.org/doctrine.htm#dormition Comparison of the Assumption and the Dormition of Mary

- ↑ http://www.east2west.org/doctrine.htm#IC Explanation of the Immaculate Conception from an Eastern Catholic perspective

- ↑ http://www.assumptioncatholicchurch.net/ Many Eastern Catholic churches bear the titles of Latin Church doctrines such as the Assumption of Mary.

- ↑ Langan, The Catholic Tradition (1998), p. 118

- ↑ Parry, The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity (1999), p. 292

- ↑ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity (2002), pp. 254–60