Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati

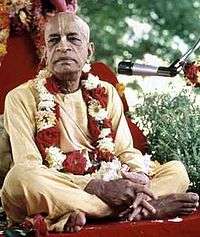

| Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura Bengali: ভক্তিসিদ্ধান্ত সরস্বতী | |

|---|---|

|

Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati editing an article. ca.1930s | |

| Born |

Bimala Prasad Datta 6 February 1874 Puri, Indian Empire |

| Died |

1 January 1937 (aged 62) Calcutta, Indian Empire |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Titles/honours |

Siddhanta Sarsvati ("the pinnacle of wisdom"); propagator of Gaudiya Vaishnavism; founder of the Gaudiya Math; acharya-keshari (lion-guru) |

| Founder of | Gaudiya Math |

| Guru | Gaurakisora Dasa Babaji |

| Philosophy | Achintya Bheda Abheda |

| Literary works | Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati bibliography |

| Notable disciple(s) | Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada and others |

| Quotation | Let me not desire anything but the highest good for my worst enemy. |

| Signature |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

|

Sampradayas |

|

Philosophers–acharyas |

|

Related traditions |

|

|

| Part of a series on | ||

| Hindu philosophy | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Orthodox schools | ||

|

|

||

| Śramaṇic schools | ||

|

|

||

|

||

Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati (Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī; Bengali: ভক্তিসিদ্ধান্ত সরস্বতী; Bengali: [bʱɔktisid̪d̪ʱanto ʃɔrɔʃbɔti]; 6 February 1874 – 1 January 1937), born Bimala Prasad Datta (Bimalā Prasād Datta, Bengali: [bimɔla prɔʃad d̪ɔt̪t̪o]), also referred to as Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, was a prominent guru and spiritual reformer of Gaudiya Vaishnavism in the early 20th century in India.

Bimala Prasad was born in 1874 in Puri (Orissa) a son of Kedarnath Datta Bhaktivinoda Thakur, a recognised Bengali Gaudiya Vaishnava philosopher and teacher. Bimala Prasad received both Western and traditional Indian education and gradually established himself as a leading intellectual among the bhadralok (Western-educated and often Hindu Bengali residents of colonial Calcutta), earning the title Siddhanta Sarasvati ("the pinnacle of wisdom"). Under the direction of his father and spiritual preceptor, Bimala Prasad took initiation (diksha) into Gaudiya Vaishnavism from the Vaishnava ascetic Gaurakishora Dasa Babaji, receiving the name Shri Varshabhanavi-devi-dayita Dasa (Śrī Vārṣabhānavī-devī-dayita Dāsa, "servant of Krishna, the beloved of Radha"), and dedicated himself to arduous ascetic discipline, recitation of the Hare Krishna mantra on beads (japa), and study of classical Vaishnava literature.

After the deaths of his father and his guru, in 1918 Bimala Prasad accepted the Hindu formal order of asceticism (sannyasa), becoming known as Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Goswami. In the same year Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati inaugurated in Calcutta the first center of his institution, later known as the Gaudiya Math. It soon developed into a dynamic missionary and educational institution with sixty-four branches across India and three centres abroad (in Burma, Germany, and England). The Math propagated the teachings of Gaudiya Vaishnavism by means of daily, weekly, and monthly periodicals, books of the Vaishnava canon, and public programs as well as through such innovations as "theistic exhibitions" with dioramas. Known for his intense and outspoken oratory and writing style as the "acharya-keshari" ("lion guru"). Bhaktisiddhanta opposed the monistic interpretation of Hinduism, or advaita, that had emerged as the prevalent strand of Hindu thought in India, seeking to establish traditional personalist krishna-bhakti as its fulfilment and higher synthesis. At the same time, through lecturing and writing, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati targeted both the ritualistic casteism of smarta brahmanas and sensualised practices of numerous Gaudiya Vaishavism spin-offs , branding them as apasampradayas – deviations from the original Gaudiya Vaishnavism taught in the 16th century by Caitanya Mahaprabhu and his close successors.

The mission initiated by Bhaktivinoda and developed by Bhaktisiddhanta emerged as "the most powerful reformist movement" of Vaishnavism in Bengal of the 19th and early 20th century. However, after the demise of Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati in 1937, the Gaudiya Math became tangled by internal dissent, and the united mission in India was effectively fragmented. Over decades, the movement regained its momentum. In 1966 its offshoot, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), was founded by Bhaktisiddhanta's disciple Bhaktivedanta Swami in New York City and spearheaded the spread of Gaudiya Vaisnava teachings and practice globally. The Bhaktisiddhanta's branch of Gaudiya Vaishnavism presently counts over 500,000 adherents worldwide, with its public profile far exceeding the size of its constituency.

Early period (1874–1900): Student

Birth and childhood

(right) Bhagavati Devi (−1920), the mother of Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, ca.1910s

Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati was born Bimala Prasad at 3:30 pm on 6 February 1874 in Puri – a town in the Indian state of Orissa famous for its ancient temple of Jagannath.[1] The place of his birth was a house his parents rented from a Calcutta businessman Ramacandra Arhya, situated a few hundred meters away from the Jagannath temple on Puri's Grand Road, the traditional venue for the renowned Hindu Ratha-yatra festival.[2]

Bimala Prasad was the seventh of fourteen children of his father Kedarnath Datta and mother Bhagavati Devi, devout Vaishnavas of the Bengali kayastha community.[1][3][lower-alpha 1] At that time Kedarnath Datta worked as a deputy magistrate and deputy collector,[6] and spent most of his off-hours studying Sanskrit and the theistic Bhagavata Purana text (also known as the Shrimad Bhagavatam) under the guidance of local pandits. He researched, translated, and published Gaudiya Vaishnava literature as well as wrote his own works on Vaishnava theology and practice in Bengali, Sanskrit, and English.[3][7]

The birth of Bimala Prasad concurred with the rising influence of the bhadralok community, literally "gentle or respectable people",[8]a privileged class of Bengalis, largely Hindus, who served the British administration in occupations requiring Western education, and proficiency in English and other languages.[9] Exposed to and influenced by the Western values of the British, including their condescending attitude towards cultural and religious traditions of India, the bhadralok themselves started questioning and reassessing the tenets of their own religion and customs.[10] Their attempts to rationalise and modernise Hinduism to reconcile it with the Western outlook eventually gave rise to a historical period called the Bengali renaissance, championed by such prominent reformists as Rammohan Roy and Swami Vivekananda.[11][12] This trend gradually led to a widespread perception, both in India and in the West, of modern Hinduism as being equivalent to Advaita Vedanta, a conception of the divine as devoid of form and individuality that was hailed by its proponents as the "perennial philosophy"[13] and "the mother of religions".[14] As a result, the other schools of Hinduism, including bhakti, were gradually relegated in the minds of the Bengali Hindu middle-class to obscurity, and were often seen as a "reactionary and fossilized jumble of empty rituals and idolatrous practices."[12][14]

Second row: Kamala Prasad, Shailaja Prasad, unknown grandchild, and Hari Pramodini.

Front row: two unknown grandchildren.

At the same time, nationalistic ferments in Calcutta, the then capital of the British Empire in South Asia, social instability in Bengal, coupled with British influence through Christian and Victorian sensibilities contributed to a portrayal of the hitherto popular worship of Radha-Krishna and Caitanya Mahaprabhu as irrelevant and deeply immoral.[12] The growing public disapproval of Gaudiya Vaishnavism was aggravated by the prevalently lower social status of local Gaudiya Vaishnavas, as well as by erotic practices of tantrics such as the sahajiyas, who claimed close affiliation with the mainstream Gaudiya school.[12] These negative perceptions led to the slow decline of Vaishnava culture and pilgrimage sites in Bengal such as Nabadwip, the birthplace of Caitanya.[16]

To avert the decay of Vaishnavism in Bengal and the spread of nondualism among the bhadralok, Vaishnava intellectuals of the time formed a new religious current led by Sisir Kumar Ghosh (1840–1911) and his brothers. In 1868 the Ghosh brothers launched the pro-Vaishnava Amrita Bazar Patrika that pioneered as one of the most popular patriotic English-medium newspapers in India and "kept Vaishnavism alive among the middle class".[3][17]

The father of Bimala Prasad, Kedarnath Datta, was also a prominent member of this circle among Gaudiya Vaishnava intelligentsia and played a significant role in their attempts to revive Vaishnavism.[3][17] (His literary and spiritual achievements later earned him the honorific title Bhaktivinoda).[18][19]

After being posted in 1869 to Puri as a deputy magistrate,[20] Kedarnatha Datta felt he needed assistance in his attempts to promote the cause Gaudiya Vaisnavism in India and abroad. A hagiographic account has it that one night the Deity of Jagannath personally spoke to Kedarnath in a dream: "I didn't bring you to Puri to execute legal matters, but to establish Vaishnava siddhanta." Kedarnath replied, "Your teachings have been significantly [sic] depreciated, and I lack the power to restore them. Much of my life has passed and I am otherwise engaged, so please send somebody from Your personal staff so that I can start this movement". Jagannath then requested Kedarnath to pray for an assistant to the image of the Goddess Bimala Devi worshiped in the Jagannath temple.[21] When his wife gave birth to a new child, Kedarnath linked the event to the divinatory dream and named his son Bimala Prasad ('"the mercy of Bimala Devi").[22] The same account mentions that at his birth, the child's umbilical cord was looped around his body like a sacred brahmana thread (upavita) that left a permanent mark on the skin, as if foretelling his future role as religious leader.[2]

Education

Young Bimala Prasad, often affectionately called Bimala, Bimu or Binu,[23] started his formal education at an English school at Ranaghat. In 1881 he was transferred to the Oriental Seminary of Calcutta and in 1883, after Kedarnath was posted as senior deputy magistrate in Serampore of Hooghly, Bimala Prasad was enrolled in the local school there.[24] At the age of nine he memorised the seven hundred verses of the Bhagavad Gita in Sanskrit.[25] From his early childhood Bimala Prasad demonstrated a sense of strict moral behaviour, a sharp intelligence, and an eidetic memory.[26][27] He gained a reputation for remembering passages from a book on a single reading, and soon learned enough to compose his own poetry in Sanskrit.[24] His biographers stated that even up to his last days Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati could verbatim recall passages from books that he had read in his childhood, earning the epithet "living encyclopedia".[28][27]

In the early 1880s, Kedarnath Datta, out of desire to foster the child's budding interest in spirituality, initiated him into harinama-japa, a traditional Gaudiya Vaishnava practice of meditation based on the soft recitation of the Hare Krishna mantra on tulasi beads.[25]

In 1885 Kedarnath Datta established the Vishva Vaishnava Raj Sabha (Royal World Vaiṣṇava Association); the association composed of leading Bengali Vaishnavas stimulated Bimala's intellectual and spiritual growth and inspired him to undertake an in-depth study of Vaishnava texts, both classical and contemporary.[3] Bimala's interest in the Vaishnava philosophy was further fuelled by the Vaishnava Depository, a library and a printing press established by Kedarnath Datta (by that time respectfully addressed as Bhaktivinoda Thakur) at his own house for systematically presenting Gaudiya Vaishnavism.[3] In 1886 Bhaktivinoda began publishing a monthly magazine in Bengali, Sajjana-toshani ("The source of pleasure for devotees"), where he published his own writings of the history and philosophy of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, along with book reviews, poetry, and novels.[3] Twelve-year-old Bimala Prasad assisted his father as a proofreader, thus closely acquainting himself with the art of printing and publishing as well as with the intellectual discourses of the bhadralok.[3]

In 1887 Bimala Prasad joined the Calcutta Metropolitan Institution (from 1917 – Vidyasagar College), which provided substantial modern education to the bhadralok youth; there, while studying the compulsory subjects, he pursued extracurricular studies of Sanskrit, mathematics, and jyotisha (traditional Indian astronomy).[29] His proficiency in the latter was soon recognised by his tutors with an honorary title "Siddhanta Sarasvati", which he adopted as his pen name from then on.[30] Sarasvati then entered Sanskrit College, one of Calcutta's finest schools for classical Hindu learning, where he added Indian philosophy and ancient history to his study list.[31]

Teaching

In 1895 Siddhanta Sarasvati decided to discontinue his studies at Sanskrit College due to a dispute about the astronomical calculations of the principal, Mahesh Chandra Nyayratna.[32] A good friend of his father, the King of Tripura Bir Chandra Manikya, offered Sarasvati a position as secretary and historian at the royal court,[33] which afforded him enough financial independence for pursuing his studies independently.[3] Taking advantage of his access to the royal library, he pored over both Indian and Western works of history, philosophy, and religion,[3] and started his own astronomy school in Calcutta.[3] After the king died in 1896, his heir Radha Kishore Manikya requested Sarasvati to tutor the princes at the palace and offered him full pension, which Siddhanta Sarsvati accepted till 1908.[3]

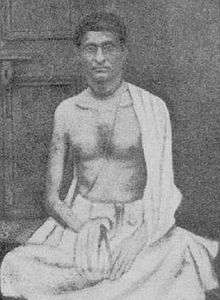

Although equipped with an excellent modern and traditional education, and with an enviable social status among the intellectual and political elite of Calcutta and Tripura along with the resources that it had brought, Siddhanta Sarasvati nonetheless began to question his choices at a stage that many would regard as the epitome of success.[34] His soul-searching led him to quit the comforts of his bhadralok lifestyle and search for an ascetic spiritual teacher.[34] On Bhaktivinoda's direction, he approached Gaurakishora Dasa Babaji, a Gaudiya Vaishnava who regularly visited Bhaktivinoda's house and was renowned for his asceticism and bhakti.[34] In January 1901, according to his own testimony, Siddhanta Sarasvati accepted the Babaji as his guru.[35][lower-alpha 2] According to the Vaishnava tradition, along with his initiation (diksha) he received a new name, Shri Varshabhanavi-devi-dayita Dasa (Śrī Vārṣabhānavī-devī-dayita Dāsa, "servant of Krishna, the beloved of Radha"), which he adopted until new titles were conferred upon him.[34]

Middle period (1901–1918): Ascetic

Religious practice

The encounter with and initiation from Gaurakishora Dasa Babaji, an illiterate yet highly respected personality, had a transformational effect on Siddhanta Sarasvati.[36][37] Later, reflecting on his first meeting with the guru, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati recalled:

It was by providential dispensation that I was able fully to understand the language and practical side of devotion after I had met the practicing master [Gaura Kishora Das Babaji]....No education could have prepared me for the good fortune of understanding my master's attitude....Before I met him my impression was that the writings of the devotional school could not be fully realised in a practical life in this world. My study of my master, and then the study of the books, along with the explanations by Thakura Bhaktivinoda [Bhaktisiddhanta's father Kedarnatha Datta], gave me ample facility to advance toward true spiritual life. Before I met my master, I had not written anything about real religion. Up to that time, my idea of religion was confined to books and to a strict ethical life, but that sort of life was found imperfect unless I came in touch with the practical side of things.[36]

After receiving initiation, Siddhanta Sarasvati went on a pilgrimage of India's holy places. He first stayed for a year in Jagannath Puri, and in 1904 travelled to South India, where he explored various branches of Hinduism, in particular the ancient and vibrant Vaishnava Shri and Madhva sampradayas, collecting materials for a new Vaishnava encyclopaedia.[34][37] He finally settled in Mayapur 130 km north of Calcutta, where Bhaktivinoda had acquired a plot of land at the place at which, according to his research, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu was born in 1486.[34] At that time, Bhaktivinoda added the prefix "bhakti" (meaning "devotion") to Siddhanta Sarasvati, acknowledging his proficiency in Vaishnava studies.[34]

Starting from 1905, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati began to deliver public discourses on the philosophy and practice of Chaitanya Vaishnavism, gathering a following of educated young Bengalis, some of whom became his students.[38] While assisting Bhaktivinoda in his developing project in Mayapur, Bhaktisiddhanta vowed to recite one billion names of Radha (Hara) and Krishna – which took nearly ten years to complete – thus committing himself to the lifelong practice of meditation on the Hare Krishna mantra taught to him first by his father and then by his guru.[39] The aural meditation on Krishna's names done either individually (japa) or collectively (kirtana) became a pivotal theme in Bhaktisiddhanta's teachings and personal practice.[39]

Brahmanas vs. Vaishnavas

While not feeling in any way "inferior" due to his birth in a comparatively lower kayastha family, Bhaktisiddhanta soon faced opposition from the orthodox brahmanas of Nabadwip, who maintained that birth in a brahminical family was a necessary criterion for worshiping the images and deities of Vishnu.[40] Refusing to submit to caste hierarchies and hereditary rights, instead Bhaktisiddhanta tried to align religious competence with personal character and religious merits.[40]

A defining moment of this brewing confrontation came on 8 September 1911, when Bhaktisiddhanta was invited to a conference in Balighai, Midnapore, that gathered Vaishnavas from Bengal and beyond to debate the eligibility of the brahmanas and that of the Vaishnavas. The debate was centred on two issues: whether those born as non-brahmanas but initiated into Vaishnavism were eligible to worship a shalagram shila (a sacred stone representing Vishnu, Krishna or other deities), and whether they could give initiation in the sacred mantras of the Vaisnava tradition.[41]

Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati accepted the invitation and presented a paper, Brāhmaṇa o Vaiṣṇava (Brahmana and Vaishnava), later published in an extended form. This became to be the first detailed exposition of Bhaktisiddhanta's thought in this matter that would lay the foundation of his forthcoming Gaudiya Math mission.[41][42] After praising the important position that brahmanas hold as repositories of spiritual and ritual knowledge, Bhaktisiddhanta used textual references to assert that Vaishnavas should be respected even more due to their devotional practice, thus contradicting the claims of the hereditary brahmanas present at the conference.[42] He described the varnashrama and its concomitant rituals of purity (samskara) as beneficial for the individual, but also as currently plagued by misguided practices.[42]

Although the debate at Balighai apparently turned into Bhaktisiddhanta's triumph, it sowed the seed of a bitter rivalry between the brahmana community of Nabadwip and the Gaudiya Math that lasted throughout Bhaktisiddhanta's life and even threatened it on a few occasions.[43][lower-alpha 3]

Publishing

Gaurakishora Dasa Babaji on several occasions dissuaded Bhaktisiddhanta from visiting Calcutta, referring to the large imperial city as "the universe of Kali" (kalira brahmanda) – a standard understanding among Vaishnava ascetics.[47] However, in 1913 Bhaktisiddhanta established a printing press in Calcutta, and called it bhagavat-yantra ("God's machine")[48] and began to publish medieval Vaishnava texts in Bengali, such as the Chaitanya Charitamrita by Krishnadasa Kaviraja, supplemented with his own commentary. This marked Bhaktisiddhanta's commitment to leave no modern facilities unused in the propagation of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, and his new focus on printing and distributing religious literature.[49] Bhaktisiddhanta's new determination stemmed from an instruction that he received in 1910 from Bhaktivinoda in a personal letter:

Sarasvati! ...Because pure devotional conclusions are not being preached, all kinds of superstitions and bad concepts are being called devotion by such pseudo-sampradayas as sahajiya and atibari. Please always crush these anti-devotional concepts by preaching pure devotional conclusions and by setting an example through your personal conduct. ...Please try very hard to make sure that the service to Sri Mayapur will become a permanent thing and will become brighter and brighter every day. The real service to Sri Mayapur can be done by acquiring printing presses, distributing devotional books, and sankirtan – preaching. Please do not neglect to serve Sri Mayapur or to preach for the sake of your own reclusive bhajan. ...I had a special desire to preach the significance of such books as Srimad Bhagavatam, Sat Sandarbha, and Vedanta Darshan. You have to accept that responsibility. Sri Mayapur will prosper if you establish an educational institution there. Never make any effort to collect knowledge or money for your own enjoyment. Only to serve the Lord will you collect these things. Never engage in bad association, either for money or for some self-interest.[50][lower-alpha 4]

After the demise of his father Bhaktivinoda on 23 June 1914, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati relocated his Calcutta press to Mayapur and then to nearby Krishnanagar in the Nadia district.[49] From there he continued publishing Bhaktivinoda's Sajjana-toshani, and completed the publication of Chaitanya Charitamrita.[49] Soon after, his guru Gaurakishora Dasa Babaji also died. Without these two key sources of inspiration, and with the majority of Bhaktivinoda's followers being married and thus unable to pursue a strong missionary commitment, Bhaktisiddhanta found himself nearly alone with a mission that seemed far beyond his means.[49] When a disciple suggested that Bhaktisiddhanta relocate to Calcutta to establish a center there, he was inspired by the suggestion and began preparing for its implementation.[49]

Later period (1918–1937): Missionary

The death of Bhaktivinoda and Gaurakishora Dasa Babaji left Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati with the burden of responsibility for their mission of reviving and safeguarding the Chaitanya tradition as they envisioned it.[52] An uncompromising and even belligerent advocate of his spiritual predecessors' teachings, Bhaktisiddhanta saw battles to be fought on many fronts: the smarta-brahmanas with their claims of exclusive hereditary eligibility as priests and gurus; the advaitins dismissing the form and personhood of God as material and external to the essence of the divine; professional Bhagavatam reciters exploiting the text sacred to Gaudiya Vaishnavas as a family business; the pseudo-Vaishnava sahajiyas and other Gaudiya spin-offs with their sensualised, profaned imitations of bhakti; and babajis professing to be ascetic renunciates but secretly indulging in erotic pleasures.[53] Relentless and uncompromising oratory and written critique of what, in Bhaktisiddhanta's words, was a contemporary religious "society of cheaters and the cheated"[53] became the underlying tone of his missionary efforts, not only earning him the title "acharya-keshari" ("lion guru"),[54] but also awakening suspicion, fear, and at times hate among his opponents.[53]

Sannyasa and Gaudiya Math

Deliberating on how to best conduct the mission in the future, he felt that the example of the South Indian orders of sannyasa (monasticism), the most prestigious spiritual order in Hinduism, would be needed in the Chaitanya tradition as well to increase its respectability and to openly institutionalise asceticism as compatible with bhakti.[52] On 27 March 1918, before leaving for Calcutta, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati resolved to become the first sannyasi of his mission, inaugurating a new Gaudiya Vaishnava monastic order. Since there was no other Gaudiya Vaishnava sannyasi to initiate him into the renounced order, he controversially sat down before a picture of his guru Gaurakishora Dasa Babaji and conferred the order upon himself.[52] From that day on, he adopted both the dress and the life of a Vaishnava renunciant, with the name Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Goswami.[52]

In December 1918 Bhaktisiddhanta inaugurated his first center called "Calcutta Bhaktivinoda Asana" at 1, Ultadinghee Junction Road in North Calcutta, renamed in 1920 as "Shri Gaudiya Math".[56] Amrita Bazar Patrika's coverage of the opening states that "[h]ere ardent seekers after truth are received and listened to and solutions to their questions are advanced from a most reasonable and liberal standpoint of view."[57] Bhaktivinoda Asana provided its students with accommodation, training in self-discipling and intense spiritual practice, as well as systematic long-term education in various Vaishnava texts such as the Shrimad Bhagavatam and Vaishnava Vedanta.[57] It would become a template for sixty-four Gaudiya Math centres in India and three abroad, in London (England), Berlin (Germany), and Rangoon (Burma), which Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati established during his lifetime.[58]

Registered on 5 February 1919, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati's missionary movement was initially called Vishva Vaishnava Raj Sabha, in the name of the society founded by Bhaktivinoda. However, it soon became eponymously known as the Gaudiya Math after the Calcutta branch and his weekly Bengali magazine Gaudiya.[59] The Gaudiya Math rapidly gained a reputation as an outspoken voice on religious, philosophical and social issues via its wide range of periodical publications, targeting educated audiences in English, Bengali, Assamese, Odia, and Hindi. These publications included a daily Bengali newspaper Nadiya Prakash, a weekly magazine Gaudiya, and a monthly magazine in English and Sanskrit The Harmonist (Shri Sajjana-toshani).[49] The intellectual and philosophical appeal of the Gaudiya Math outreach programs garnered particularly eager response in urban areas, where wealthy supporters started contributing generously towards the construction of new temples and large "theistic exhibitions" – public expositions on the Gaudiya Vaishnava philosophy by means of displays and dioramas.[49]

Caste and untouchability

The Gaudiya Math core leadership consisted mainly of educated Bengalis and eighteen sannyasis[60] who were sent off to pioneer the movement in new places in India, and later, in Europe.[61] Its growing ashrama residents hub, however, represented a wide cross-section of the Indian society, with disciples from both educated urban and simple rural milieus.[61] Householder disciples and sympathizers supported the temples with funds, food, and volunteer labour. The Gaudiya Math centres paid serious attention to the individual discipline of their residents, including mandatory ascetic vows and daily practice of devotion (bhakti) centred on individual recitation (japa) and public singing (kirtan) of Krishna's names, regular study of philosophical and devotional texts (svadhyaya), traditional worship of temple images of Krishna and Chaitanya (archana) as well as attendance at lectures and seminars (shravanam).[61]

A deliberate disregard of social background as a criteria for religious eligibility marked a sharp departure in Bhaktisiddhanta's movement from customary Hindu caste restrictions.[61] Bhaktisiddhanta spelled out his views, which appeared to be modern yet were firmly rooted in the early bhakti literature of the Chaitanya school, in an essay called "Gandhiji's Ten Questions" published in The Harmonist in January 1933.[62] In the essay he replied to questions posed by Mahatma Gandhi, who in December 1932 challenged India's leading orthodox Hindu organisations on the practice of untouchability.[62] In his reply, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati defined untouchables as those inimical to the concept of serving God, rather than those hailing from the lowest social or hereditary background.[62] He argued that Vishnu temples should be open to everyone, but particularly to those who possessed a favourable attitude toward the divine and were willing to undergo a process of spiritual training.[62] He further stated that untouchability had a cultural and historical underpinning rather than a religious one, and as such, Gandhi's questions referred to a secular issue, not a religious one. As an alternative to the secular concept of "Hindu" and its social implications, Bhaktisiddhanta suggested an ethic of "unconditional reverence for all entities by the realization and exclusive practice of the whole-time service of the Absolute".[62] By this he stressed that the practice of bhakti, or divine love, and service to God as the supreme person demanded moral responsibility towards all other beings who, according to Chaitanya school, are eternal metaphysical entities – minute in relation to God but qualitatively equal to one another.[62]

Love vs. renunciation

While emphasising the innate spirituality of all beings, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati strongly objected to representations of the sacred love between Radha and Krishna, described in the Bhagavatam and other Vaishnava texts, as erotic, which permeated the popular culture of Bengal in art, theatre, and folk songs.[63] He stated that the sacred concept of love cherished by Gaudiya Vaishnavas was being profaned due to a lacking in philosophical understanding and proper guidance. He repeatedly critiqued such popular communities in Bengal as the sahajiyas, who presented their sexual practices as a path of Krishna bhakti, denouncing them as pseudo-Vaishanas.[63] Bhaktisiddhanta argued instead that the path to spiritual growth was not through what he described as sensual gratification, but through the practice of chastity, humility, and service.[63]

At the same time, Bhaktisiddhanta's approach to the material world was far from being escapist. Rather than shunning all connections with it, he adopted the principle of yukta-vairagya – a term coined by Chaitanya's associate Rupa Gosvami meaning "renunciation by engagement". This implied using any required object in the service of the divine by renouncing the propensity to enjoy it.[64] [65] On the basis of this principle, Bhaktisiddhanta used the latest advancements in technology, institutional building, communication, printing, and transportation, while striving to carefully keep intact the theological core of his personalist tradition.[66] This hermeneutical dynamism and spirit of adaptation employed by Bhaktisiddhanta became an important element in the growth of the Gaudiya Math and facilitated its future global growth.[65]

The Gaudiya Math in Europe

Back in 1882, Bhaktivinoda stated in his Sajjana-toshani magazine a coveted vision of universalism and brotherhood across borders and races:

When in England, France, Russia, Prussia, and America all fortunate persons by taking up kholas [drums] and karatalas [cymbals] will take the name of Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu again and again in their own countries, and raise the waves of sankirtana [congregational singing of Krishna's names], when will that day come! Oh! When will the day come when the white-skinned British people will speak the glory of Shri Shachinandana [another name of Chaitanya] on one side and on the other and with this call spread their arms to embrace devotees from other countries in brotherhood, when will that day come! The day when they will say "Oh, Aryan Brothers! We have taken refuge at the feet of Chaitanya Deva in an ocean of love, now kindly embrace us," when will that day come![67]

Bhaktivinoda did not stop short of making practical efforts to implement his vision. In 1896 he published and sent to several addressees in the West a book entitled Srimad-Gaurangalila- Smaranamangala, or Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, His life and Precepts[lower-alpha 5] that portrayed Chaitanya Mahaprabhu as a champion of "universal brotherhood and intellectual freedom":

Caitanya preaches equality of men ...universal fraternity amongst men and special brotherhood amongst Vaishnavas, who are according to him, the best pioneers of spiritual improvement. He preaches that human thought should never be allowed to be shackled with sectarian views....The religion preached by Mahaprabhu is universal and not exclusive. The most learned and the most ignorant are both entitled to embrace it. . . . The principle of kirtana invites, as the future church of the world, all classes of men without distinction of caste or clan to the highest cultivation of the spirit.[67]

Bhaktivinoda adapted his message to the Western mind by borrowing popular Christian expressions such as "universal fraternity", "cultivation of the spirit", "preach", and "church" and deliberately using them in a Hindu context.[68] Copies of Shri Chaitanya, His Life and Precepts were sent to Western scholars across the British Empire, and landed, among others, in academic libraries at McGill University in Montreal, at the University of Sydney in Australia and at the Royal Asiatic Society of London. The book also made its way to prominent scholars such as Oxford Sanskritist Monier Monier-Williams and earned a favourable review in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society.[67][69]

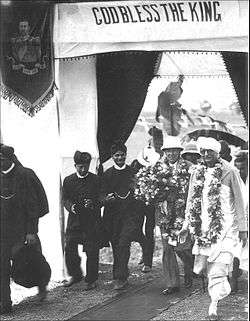

Bhaktisiddhanta inherited the vision of spreading the message of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu in the West from his father Bhaktivinoda. The same inspiration was also bequeathed to Bhaktisiddhanta as the last will of his mother Bhagavati Devi prior to her deathin 1920.[70] Thus, from the early 1920s Bhaktisiddhanta began to plan is mission to Europe.

In 1927 he launched a periodical in English and requested British officers to patronise his movement, which they gradually did, culminating in an official visit by the Governor of Bengal John Anderson to Bhaktisiddhanta's headquarters in Mayapur on 15 January 1935.[71] Bhaktisiddhanta is reported to have kept a map of London, pondering on ways of expanding his mission to new frontiers in the West.[72] After a long and careful preparation, on 20 July 1933 three of Bhaktisiddhanta's senior disciples including Swami Bhakti Hridaya Bon arrived in London.[65][72] As a result of their mission abroad, on 24 April 1934, Lord Zetland, the British secretary of state for India, inaugurated the Gaudiya Mission Society in London and became its president. This was followed a few months later by a center established by Swami Bon in Berlin, Germany, from where he journeyed to lecture and meet the German academic and political elite.[65][72] On 18 September 1935, the Gaudiya Math and Calcutta dignitaries offered a reception to two German converts, Ernst Georg Schulze and Baron H.E. von Queth, who arrived along with Swami Bon.[65]

Bhaktisiddhanta maintained that, if explained properly, the philosophy and practice of Vaishnavism would speak for itself, gradually attracting intelligent and sensible people.[73] However, despite considerable financial investments and efforts, the success of the Gaudiya Mission in the West remained limited to just a few people interested to seriously practice Vaishnavism.[72] The importance of the Western venture prompted Bhaktisiddhanta to make the Western mission the main theme of his final address at a gathering of thousands of his disciples and followers at Champahati, Bengal, in 1936.[70] In his address Bhaktisiddhanta restated the urgency and importance of presenting Chaitanya's teachings in the Western countries, despite all social, cultural, and financial challenges, and told, "I have a prediction. However long in the future it may be, one of my disciples will cross the ocean and bring back the entire world".[70]

The deep international tensions globally building up in the late 1930s made Bhaktisiddhanta more certain that solutions to the incumbent problems of humanity were to be found primarily in the realm of religion and spirituality, and not solely in the fields of science, economy, and politics.[74] On 3 December 1936, Bhaktisiddhanta answered a letter from his disciple Abhay Caranaravinda De, who had asked how he could best serve his guru's mission:

I am fully confident that you can explain in English our thoughts and arguments to the people who are not conversant with the languages of other members. This will do much good to yourself as well as your audience. I have every hope that you can turn yourself [into] a very good English preacher if you serve the mission to inculcate the novel impression to the people in general and philosophers of [sic] modern age and religiosity.[75]

Shortly thereafter, on 1 January 1937, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati died at the age of 63.[65]

Literary works

- For a complete list of Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati's literary works, see Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati bibliography

Crises of succession

The Gaudiya Math mission, inspired by Bhaktivinoda and developed by Bhaktisiddhanta, emerged as one of "the most powerful reformist movements" of colonial Bengal in the 19th and early 20th century.[76] In mission and scope it parallelled the efforts of Swami Vivekananda and the Ramakrishna Mission, and challenged modern advaita Vedanta spirituality that had come to dominate the religious sensibilities of the Hindu middle class in India and the way Hinduism was understood in the West.[77] Rather than appointing a successor, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati instead instructed his leading disciples to jointly run the mission in his absence, and expected that qualified leaders would emerge naturally "on the strength of their personal merit".[78] However, weeks after his departure a crisis of succession broke out, resulting in factions and legal infighting.[78] The united mission was first split into two separate institutions and later on was fragmented into several smaller groups that began functioning and furthering the movement independently.[78]

The Gaudiya Math movement, however, slowly regained its strength. In 1966 Abhay Caranararavinda De, now A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, founded in New York City the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON).[79] Modeled after the original Gaudiya Math and emulating its emphasis on dynamic mission and spiritual practice, ISKCON soon popularised Chaitanya Vaishnavism on a global scale, becoming a world's leading proponent of Hindu bhakti personalism.[79][80]

Today Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati's Gaudiya Math movement includes more than forty independent institutions, hundreds of centres and more than 500,000 practitioners globally, with scholars acknowledging its public profile as far exceeding the size of its constituency.[81]

Notes

- ↑ According to upper-class Hindu customs, in 1850 Kedarnath Datta, 11, was married with Sayamani, 5. In 1860 Sayamani gave birth to Kedarnath's first son, Annada Prasad, and died of illness shortly thereafter. Kedarnath soon married Bhagavati Devi and had thirteen children with her: (1) Saudamani, daughter (1864); (2) Kadambani, daughter (1867); (3) son died early, name unknown (1868); (4) Radhika Prasad, son (1870); (5) Kamala Prasad (1872); (6) Bimala Prasad, son (1874); (7) Barada Prasad (1877); (8) Biraja, daughter, (1878); (9) Lalita Prasad, son (1880); (10) Krishna Vinodini, daughter (1884); (11) Shyam Sarojini, daughter (1886); (12) Hari Pramodini, daughter (1888); (13) Shailaja Prasad, son (1891).[1][4][5] This makes Bimala Prasad the seventh child of Kedarnath and the sixth of Bhagavati.

- ↑ While it is still being debated what kind of diksha – pancaratrika (into a mantra) or bhagavata (into the name of Krishna) – did Bhaktisiddhanta receive from Gaurakishora Dasa Bababji, there are indications in his own writings that he received the Hare Krishna mantra along with an instruction to chant it a certain number of times a day.[35]

- ↑ There have been a few documented attempts on Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati's life.[44] On one such incident in 1925, when the attackers ambushed Bhaktisiddhanta's party, his disciple Vinoda Vihari volunteered to exchange clothes with him, allowing Bhaktisiddhanta a safe escape.[45] [46]

- ↑ The original letter was never recovered; however, Bhaktisiddhanta quoted these instructions by Bhaktivinoda, apparently considering them as seminal for his mission, in a 1926 letter thus:[51]

- Persons who claim worldly prestige and futile glory fail to attain the true position of nobleness, because they argue that Vaishnavas are born in a low position as a result of [previous] sinful actions, which means that they commit offences (aparadha). You should know that, as a remedy, the practice of varnashrama, which you have recently taken up, is a genuine Vaishnava service (seva).

- It is because of lack of promulgation of the pure conclusions of bhakti (shuddha bhaktisiddhanta) that . . . among men and women of the sahajiya groups, ativadis, and other lines (sampradaya) devious practices are welcomed as bhakti. You should always critique those views, which are opposed to the conclusions of the sacred texts, by missionary work and sincere practice of the conclusions of bhakti.

- Arrange to begin a pilgrimage (parikrama) in and around Nabadwip as soon as possible. Through this activity alone, anyone in the world may attain Krishna bhakti. Take adequate care so that service in Mayapur continues, and grows brighter day by day. Real seva in Mayapur will be possible by setting up a printing press, distributing bhakti literature (bhakti-grantha), and nama-hatta (devotional centres for the recitation of the sacred names of God), not by solitary practice (bhajana). You should not hamper seva in Mayapur and the mission (pracara) by indulging in solitary bhajana.

- When I shall not be here any more...[remember that] seva in Mayapur is a highly revered service. Take special care of it; this is my special instruction to you.

- I had a sincere desire to draw attention to the significance of pure (shuddha) bhakti through books such as Shrimad Bhagavatam, Sat-sandarbha, Vedanta-darshana, etc. You should go on and take charge of that task. Mayapur will develop if a center of devotional learning (vidyapitha) is created there.

- Never bother to acquire knowledge or funds for your personal consumption; collect them only for the purpose of serving the divine; avoid bad company for the sake of money or self-interest.

- ↑ The book was also published under slightly varied titles, such as Shri Chaitanya, His Life and Precepts.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Sardella 2013b, p. 55.

- 1 2 Swami 2009, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Sardella 2013a, p. 416.

- ↑ Dasa 1999, p. 300.

- ↑ Swami 2009, p. 6.

- ↑ Dasa 1999, pp. 77, 298.

- ↑ Dasa 1999, p. 78.

- ↑ Sardella2013b, p. 17.

- ↑ Sardella2013b, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 19.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Sardella 2013a, p. 415.

- ↑ Ward 1998, pp. 35–36.

- 1 2 Ward 1998, p. 10.

- ↑ Dasa 1999, p. 84.

- ↑ Sardella 2013a, pp. 415–416.

- 1 2 Dasa 1999, p. 97.

- ↑ Dasa 1999, p. 95.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 56.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 62.

- ↑ Swami 2009, p. 5.

- ↑ Bryant & Ekstrand 2004, p. 81.

- ↑ Swami 2009, p. 9.

- 1 2 Sardella 2013b, pp. 64–65.

- 1 2 Sardella 2013b, p. 64.

- ↑ Swami 2009, p. 10.

- 1 2 Sardella 2013b, p. 65.

- ↑ Swami 2009, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 66.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 67.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 68-69.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 71.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sardella 2013a, p. 417.

- 1 2 Bryant & Ekstrand 2004, p. 85.

- 1 2 Sardella 2013b, p. 75.

- 1 2 Sardella 2013b, p. 79.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 80.

- 1 2 Sardella 2013b, p. 81.

- 1 2 Sardella 2013b, p. 82.

- 1 2 Bryant & Ekstrand 2004, p. 83.

- 1 2 3 Sardella 2013b, pp. 82–86.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 82-86.

- ↑ Goswami & Schweig 2012, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 99.

- ↑ Murphy & Goff 1997, p. 32.

- ↑ Bryant & Ekstrand 2004, p. 88.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sardella 2013a, p. 418.

- ↑ Murphy & Goff 1997, p. 18.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 87.

- 1 2 3 4 Sardella 2013b, pp. 90–91.

- 1 2 3 Goswami & Schweig 2012, p. 109.

- ↑ Swami 2009, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Swami 2009, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, pp. 92–93.

- 1 2 Sardella 2013b, pp. 92.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, pp. 92, 98.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, pp. 92–93, 98.

- ↑ Goswami & Schweig 2012, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 Sardella 2013a, pp. 418–419.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sardella 2013b, pp. 121–123.

- 1 2 3 Sardella 2013a, p. 419.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, pp. 203–208.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sardella 2013a, p. 420.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 105.

- 1 2 3 Sardella 2013b, pp. 94–96.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, pp. 94–95

- ↑ Dasa 1999, p. 91-92.

- 1 2 3 Swami 2009b, pp. 392–393.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, pp. 156–157.

- 1 2 3 4 Dwyer & Cole 2007, p. 27.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 136.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 142-143.

- ↑ Goswami & Schweig 2012, p. 112.

- ↑ Sardella & Sain 2013, p. 214.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, p. 239-242.

- 1 2 3 Sardella 2013b, pp. 129–132.

- 1 2 Sardella 2013b, pp. 246–249.

- ↑ Ward 1998, p. 36.

- ↑ Sardella 2013b, pp. 246–249, 259–260.

References

- Bryant, Edwin F.; Ekstrand, Maria L., eds. (2004), The Hare Krishna movement: The postcharismatic fate of a religious transplant ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.), New York, NY: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231122566, retrieved 15 January 2014

- Dasa, Shukavak N. (1999), Hindu Encounter with Modernity: Kedarnath Datta Bhaktivinoda, Vaiṣṇava Theologian (revised, illustrated ed.), Los Angeles, CA: Sanskrit Religions Institute, ISBN 1-889756-30-X, retrieved 31 January 2014

- Dwyer, Graham; Cole, Richard J. (2007), The Hare Krishna movement: Forty years of chant and change, London, UK: I.B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1845114077, retrieved 15 January 2014

- Goswami, Tamal Krishna; Schweig, Graham M. (concluding chapters) (2012), A living theology of Krishna Bhakti: The essential teachings of A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-979663-2, retrieved 15 January 2014

- Sardella, Ferdinando (2013a), Jacobsen, Knut A., ed., Brill's encyclopedia of Hinduism (Volume 5 ed.), Leiden, NL; Boston, US: Brill, pp. 415–423, ISBN 978-90-04-17896-0, retrieved 19 January 2014

- Murphy, Phillip; Goff, Raoul, eds. (1997), Prabhupada Sarasvati Thakur: The Life and Precepts of Srila Bhaktisidhanta Sarasvati (1st limited ed.), Eugene, OR: Mandala Publishing, ISBN 978-0945475101, retrieved 6 February 2014

- Sardella, Ferdinando (2013b), Modern Hindu Personalism: The History, Life, and Thought of Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati (reprint ed.), New York, NY: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199865901, retrieved 6 February 2014

- Sardella, Ferdinando; Sain, Ruby, eds. (2013), The sociology of religion in India: Past, present and future, New Delhi, IN: Abhijeet Publications, ISBN 978-93-5074-047-7, retrieved 16 January 2014

- Swami, Bhakti Vikasa (2009), Śrī Bhaktisiddhānta Vaibhava: The grandeur and glory of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura, 1 (in three volumes ed.), Surat, IN: Bhakti Vikas Trust, ISBN 978-81-908292-0-5, retrieved 15 January 2014

- Swami, Bhakti Vikasa (2009b), Śrī Bhaktisiddhānta Vaibhava: The grandeur and glory of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura, 2 (in three volumes ed.), Surat, IN: Bhakti Vikas Trust, ISBN 978-81-908292-0-5, retrieved 15 January 2014

- Ward, Keith (1998), Religion and human nature (Reprinted ed.), Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-826965-X, retrieved 2 February 2014

External links

Media related to Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati at Wikimedia Commons