Mandarin Chinese

| Mandarin | |

|---|---|

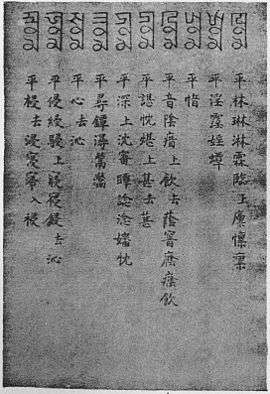

| 官话; 官話; Guānhuà | |

|

Guānhuà (Mandarin) written in Chinese characters (traditional Chinese on the left, simplified Chinese on the right) | |

| Region | Most of northern and southwestern China (see also Standard Chinese) |

Native speakers | 960 million (2010)[1] |

Early forms | |

Standard forms |

Standard Chinese

(Putonghua, Guoyu) |

| Dialects |

|

|

Traditional Chinese Simplified Chinese Cyrillic (Dungan alphabet) Xiao'erjing Mainland Chinese Braille Taiwanese Braille Two-Cell Chinese Braille Pinyin | |

| Wenfa Shouyu[2] | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

cmn |

| Glottolog |

mand1415[3] |

| Linguasphere |

79-AAA-b |

|

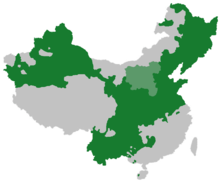

Mandarin area in China, with Jin (sometimes treated as a separate group) in light green | |

| Mandarin Chinese | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 官話 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 官话 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | officials' speech | ||||||

| |||||||

| Northern Chinese | |||||||

| Chinese | 北方話 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Northern speech | ||||||

| |||||||

Mandarin (![]() i/ˈmændᵊrɪn/; simplified Chinese: 官话; traditional Chinese: 官話; pinyin: Guānhuà; literally: "speech of officials") is a group of related varieties of Chinese spoken across most of northern and southwestern China. The group includes the Beijing dialect, the basis of Standard Chinese, which is also referred to as "Mandarin". Because most Mandarin dialects are found in the north, the group is sometimes referred to as the Northern dialects (北方话; běifānghuà). Many local Mandarin varieties are not mutually intelligible. Nevertheless, Mandarin is often placed first in any list of languages by number of native speakers (with nearly a billion).

i/ˈmændᵊrɪn/; simplified Chinese: 官话; traditional Chinese: 官話; pinyin: Guānhuà; literally: "speech of officials") is a group of related varieties of Chinese spoken across most of northern and southwestern China. The group includes the Beijing dialect, the basis of Standard Chinese, which is also referred to as "Mandarin". Because most Mandarin dialects are found in the north, the group is sometimes referred to as the Northern dialects (北方话; běifānghuà). Many local Mandarin varieties are not mutually intelligible. Nevertheless, Mandarin is often placed first in any list of languages by number of native speakers (with nearly a billion).

Mandarin is by far the largest of the seven or ten Chinese dialect groups, with 70 per cent of Chinese speakers and a huge area stretching from Yunnan in the southwest to Xinjiang in the northwest and Heilongjiang in the northeast. This is attributed to the greater ease of travel and communication in the North China Plain compared to the more mountainous south, combined with the relatively recent spread of Mandarin to frontier areas.

Most Mandarin varieties have four tones. The final stops of Middle Chinese have disappeared in most of these varieties, but some have merged them as a final glottal stop. Many Mandarin varieties, including the Beijing dialect, retain retroflex initial consonants, which have been lost in southern dialect groups.

The capital has been within the Mandarin area for most of the last millennium, making these dialects very influential. Some form of Mandarin has served as a national lingua franca since the 14th century. In the early 20th century, a standard form based on the Beijing dialect, with elements from other Mandarin dialects, was adopted as the national language. Standard Chinese is the official language of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan (Republic of China) and one of the four official languages of Singapore. It is also one of the most frequently used varieties of Chinese among Chinese diaspora communities internationally.

Name

The English word "mandarin" (from Portuguese mandarim, from Malay menteri, from Sanskrit mantrin, meaning "minister or counsellor") originally meant an official of the Ming and Qing empires.[4][5][lower-alpha 1] Since their native varieties were often mutually unintelligible, these officials communicated using a Koiné language based on various northern varieties. When Jesuit missionaries learned this standard language in the 16th century, they called it "Mandarin", from its Chinese name Guānhuà (官话/官話), or "language of the officials".[7]

In everyday English, "Mandarin" refers to Standard Chinese, which is often called simply "Chinese". Standard Chinese is based on the particular Mandarin dialect spoken in Beijing, with some lexical and syntactic influence from other Mandarin dialects. It is the official spoken language of the People's Republic of China (PRC), the official language of the Republic of China (ROC, Taiwan), and one of the four official languages of the Republic of Singapore. It also functions as the language of instruction in Mainland China and in Taiwan. It is one of the six official languages of the United Nations, under the name "Chinese". Chinese speakers refer to the modern standard language as

- Pǔtōnghuà (普通话/普通話, literally "common speech") in Mainland China,

- Guóyǔ (國語, literally "national language") in Taiwan, or

- Huáyǔ (华语/華語, literally "Hua language") in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Philippines,

but not as Guānhuà.[8]

Linguists use the term "Mandarin" to refer to the diverse group of dialects spoken in northern and southwestern China, which Chinese linguists call Guānhuà. The alternative term Běifānghuà (北方话/北方話), or "Northern dialects", is used less and less among Chinese linguists. By extension, the term "Old Mandarin" or "Early Mandarin" is used by linguists to refer to the northern dialects recorded in materials from the Yuan dynasty.

Native speakers who are not academic linguists may not recognize that the variants they speak are classified in linguistics as members of "Mandarin" (or so-called "Northern dialects") in a broader sense. Within Chinese social or cultural discourse, there is not a common "Mandarin" identity based on language; rather, there are strong regional identities centred on individual dialects because of the wide geographical distribution and cultural diversity of their speakers. Speakers of forms of Mandarin other than the standard typically refer to the variety they speak by a geographic name—for example Sichuan dialect, Hebei dialect or Northeastern dialect, all being regarded as distinct from the standard language.

History

The thousands of modern local varieties of Chinese developed from regional variants of Old Chinese and Middle Chinese. Traditionally, seven major groups of dialects have been recognized. Aside from Mandarin, the other six are Wu, Gan and Xiang in central China, and Min, Hakka and Yue on the southeast coast.[9] The Language Atlas of China (1987) distinguishes three further groups: Jin (split from Mandarin), Huizhou in the Huizhou region of Anhui and Zhejiang, and Pinghua in Guangxi and Yunnan.[10][11]

Old Mandarin

After the fall of the Northern Song (959–1126) and during the reign of the Jin (1115–1234) and Yuan (Mongol) dynasties in northern China, a common speech developed based on the dialects of the North China Plain around the capital, a language referred to as Old Mandarin. New genres of vernacular literature were based on this language, including verse, drama and story forms, such as the qu and sanqu poetry.[12]

The rhyming conventions of the new verse were codified in a rime dictionary called the Zhongyuan Yinyun (1324). A radical departure from the rime table tradition that had evolved over the previous centuries, this dictionary contains a wealth of information on the phonology of Old Mandarin. Further sources are the 'Phags-pa script based on the Tibetan alphabet, which was used to write several of the languages of the Mongol empire, including Chinese, and the Menggu Ziyun, a rime dictionary based on 'Phags-pa. The rime books differ in some details, but overall show many of the features characteristic of modern Mandarin dialects, such as the reduction and disappearance of final plosives and the reorganization of the Middle Chinese tones.[13]

In Middle Chinese, initial stops and affricates showed a three-way contrast between tenuis, voiceless aspirated and voiced consonants. There were four tones, with the fourth, or "entering tone", a checked tone comprising syllables ending in plosives (-p, -t or -k). Syllables with voiced initials tended to be pronounced with a lower pitch, and by the late Tang dynasty, each of the tones had split into two registers conditioned by the initials. When voicing was lost in all languages except the Wu subfamily, this distinction became phonemic and the system of initials and tones was rearranged differently in each of the major groups.[14]

The Zhongyuan Yinyun shows the typical Mandarin four-tone system resulting from a split of the "even" tone and loss of the entering tone, with its syllables distributed across the other tones (though their different origin is marked in the dictionary). Similarly, voiced plosives and affricates have become voiceless aspirates in the "even" tone and voiceless non-aspirates in others, another distinctive Mandarin development. However, the language still retained a final -m, which has merged with -n in modern dialects, and initial voiced fricatives. It also retained the distinction between velars and alveolar sibilants in palatal environments, which later merged in most Mandarin dialects to yield a palatal series (rendered j-, q- and x- in pinyin).[15]

The flourishing vernacular literature of the period also shows distinctively Mandarin vocabulary and syntax, though some, such as the third-person pronoun tā (他), can be traced back to the Tang dynasty.[16]

Vernacular literature

Until the early 20th century, formal writing and even much poetry and fiction was done in Literary Chinese, which was modeled on the classics of the Warring States period and the Han dynasty. Over time, the various spoken varieties diverged greatly from Literary Chinese, which was learned and composed as a special language. Preserved from the sound changes that affected the various spoken varieties, its economy of expression was greatly valued. For instance, 翼 (yì, wing) is unambiguous in written Chinese, but has over 75 homophones in Standard Chinese.

The literary language was less appropriate for recording materials that were meant to be reproduced in oral presentations, materials such as plays and grist for the professional story-teller's mill. From at least the Yuan dynasty, plays that recounted the subversive tales of China's Robin Hoods to the Ming dynasty novels such as Water Margin, on down to the Qing dynasty novel Dream of the Red Chamber and beyond, there developed a literature in written vernacular Chinese (白话/白話 báihuà). In many cases, this written language reflected Mandarin varieties, and since pronunciation differences were not conveyed in this written form, this tradition had a unifying force across all the Mandarin-speaking regions and beyond.[17]

Hu Shih, a pivotal figure of the first half of the twentieth century, wrote an influential and perceptive study of this literary tradition, entitled Báihuà Wénxuéshǐ (A History of Vernacular Literature).

Koiné of the Late Empire

The Chinese have different languages in different provinces, to such an extent that they cannot understand each other.... [They] also have another language which is like a universal and common language; this is the official language of the mandarins and of the court; it is among them like Latin among ourselves.... Two of our fathers [Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci] have been learning this mandarin language...— Alessandro Valignano, Historia del principio y progresso de la Compañía de Jesús en las Indias Orientales (1542–1564)[19]

Until the mid-20th century, most Chinese people living in many parts of South China spoke only their local variety. As a practical measure, officials of the Ming and Qing dynasties carried out the administration of the empire using a common language based on Mandarin varieties, known as Guānhuà. Knowledge of this language was thus essential for an official career, but it was never formally defined.[8]

Officials varied widely in their pronunciation; in 1728, the Yongzheng Emperor, unable to understand the accents of officials from Guangdong and Fujian, issued a decree requiring the governors of those provinces to provide for the teaching of proper pronunciation. Although the resulting Academies for Correct Pronunciation (正音書院, Zhèngyīn Shūyuàn) were short-lived, the decree did spawn a number of textbooks that give some insight into the ideal pronunciation. Common features included:

- loss of the Middle Chinese voiced initials except for v-

- merger of -m finals with -n

- the characteristic Mandarin four-tone system in open syllables, but retaining a final glottal stop in "entering tone" syllables

- retention of the distinction between palatalized velars and dental affricates, the source of the spellings "Peking" and "Tientsin" for modern "Beijing" and "Tianjin".[20]

As the last two of these features indicate, this language was a koiné based on dialects spoken in the Nanjing area, though not identical to any single dialect.[21] This form remained prestigious long after the capital moved to Beijing in 1421, though the speech of the new capital emerged as a rival standard. As late as 1815, Robert Morrison based the first English–Chinese dictionary on this koiné as the standard of the time, though he conceded that the Beijing dialect was gaining in influence.[22] By the middle of the 19th century, the Beijing dialect had become dominant and was essential for any business with the imperial court.[23]

Standard Chinese

In the early years of the Republic of China, intellectuals of the New Culture Movement, such as Hu Shih and Chen Duxiu, successfully campaigned for the replacement of Literary Chinese as the written standard by written vernacular Chinese, which was based on northern dialects. A parallel priority was the definition of a standard national language (simplified Chinese: 国语; traditional Chinese: 國語; pinyin: Guóyǔ; Wade–Giles: Kuo²-yü³). After much dispute between proponents of northern and southern dialects and an abortive attempt at an artificial pronunciation, the National Language Unification Commission finally settled on the Beijing dialect in 1932. The People's Republic, founded in 1949, retained this standard, calling it pǔtōnghuà (simplified Chinese: 普通话; traditional Chinese: 普通話; literally: "common speech").[24] Some 54% of speakers of Mandarin dialects could understand the standard language in the early 1950s, rising to 91% in 1984. Nationally, the proportion understanding the standard rose from 41% to 90% over the same period.[25]

The national language is now used in education, the media, and formal situations in both the PRC and the ROC but not in Hong Kong and Macau. This standard can now be spoken intelligibly by most younger people in Mainland China and Taiwan with various regional accents. In Hong Kong and Macau, because of their colonial and linguistic history, the language of education, the media, formal speech and everyday life remains the local Cantonese, although the standard language is now very influential and taught in schools.[26] In Mandarin-speaking areas such as Sichuan, the local dialect is the mother tongue of most of the population. The era of mass education in Standard Chinese has not erased these regional differences, and people may be either diglossic or speak the standard language with a notable accent.

From an official point of view, the PRC and ROC governments maintain their own forms of the standard under different names. Technically, both Pǔtōnghuà and Guóyǔ base their phonology on the Beijing accent, though Pǔtōnghuà also takes some elements from other sources. Comparison of dictionaries produced in the two areas will show that there are few substantial differences. However, both versions of "school-standard" Chinese are often quite different from the Mandarin dialects that are spoken in accordance with regional habits, and neither is wholly identical to the Beijing dialect. Pǔtōnghuà and Guóyǔ also have some differences from the Beijing dialect in vocabulary, grammar, and pragmatics.

The written forms of Standard Chinese are also essentially equivalent, although simplified characters are used in Mainland China, Malaysia and Singapore while people in Taiwan, Macau and Hong Kong generally use traditional characters.

Geographic distribution and dialects

Most Han Chinese living in northern and southwestern China are native speakers of a dialect of Mandarin. The North China Plain provided few barriers to migration, leading to relative linguistic homogeneity over a wide area in northern China. In contrast, the mountains and rivers of southern China have spawned the other six major groups of Chinese varieties, with great internal diversity, particularly in Fujian.[27][28]

However, the varieties of Mandarin cover a huge area containing nearly a billion people. As a result, there are pronounced regional variations in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar, and many Mandarin varieties are not mutually intelligible.[lower-alpha 2]

Most of northeastern China, except for Liaoning, did not receive significant settlements by Han Chinese until the 18th century,[33] and as a result the Northeastern Mandarin dialects spoken there differ little from the Beijing dialect.[34] The Manchu people of the area now speak these dialects exclusively; their native language is only maintained in northwestern Xinjiang, where Xibe, a modern dialect, is spoken.[35]

The frontier areas of Northwest China were colonized by speakers of Mandarin dialects at the same time, and the dialects in those areas similarly closely resemble their relatives in the core Mandarin area.[34] The Southwest was settled early, but the population fell dramatically for obscure reasons in the 13th century, and did not recover until the 17th century.[34] The dialects in this area are now relatively uniform.[36] However, long-established cities even very close to Beijing, such as Tianjin, Baoding, Shenyang, and Dalian, have markedly different dialects.

Unlike their compatriots on the southeast coast, few Mandarin speakers engaged in overseas emigration until the late 20th century, but there are now significant communities of them in cities across the world.[36]

Classification

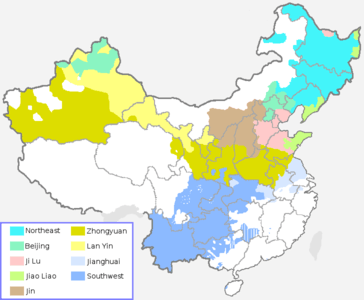

The classification of Chinese dialects evolved during the 20th century, and many points remain unsettled. Early classifications tended to follow provincial boundaries or major geographical features.[37] In 1936, Wang Li produced the first classification based on phonetic criteria, principally the evolution of Middle Chinese voiced initials. His Mandarin group included dialects of northern and southwestern China, as well as those of Hunan and northern Jiangxi.[38] Li Fang-Kuei's classification of 1937 distinguished the latter two groups as Xiang and Gan, while splitting the remaining Mandarin dialects between Northern, Lower Yangtze and Southwestern Mandarin groups.[39] The widely accepted seven-group classification of Yuan Jiahua in 1960 kept Xiang and Gan separate, with Mandarin divided into Northern, Northwestern, Southwestern and Jiang–Huai (Lower Yangtze) subgroups.[40][41]

Of Yuan's four Mandarin subgroups, the Northwestern dialects are the most diverse, particularly in the province of Shanxi.[36] The linguist Li Rong proposed that the northwestern dialects of Shanxi and neighbouring areas that retain a final glottal stop in the Middle Chinese entering tone (plosive-final) category should constitute a separate top-level group called Jin.[42] He used this classification in the Language Atlas of China (1987).[10] Many other linguists continue to include these dialects in the Mandarin group, pointing out that the Lower Yangtze dialects also retain the glottal stop.[43][44]

The southern boundary of the Mandarin area, with the central Wu, Gan and Xiang groups, is weakly defined due to centuries of diffusion of northern features. Many border varieties have a mixture of features that make them difficult to classify. The boundary between Southwestern Mandarin and Xiang is particularly weak,[45] and in many early classifications the two were not separated.[46] Zhou Zhenhe and You Rujie included the New Xiang dialects within Southwestern Mandarin, treating only the more conservative Old Xiang dialects as a separate group.[47] The Huizhou dialects have features of both Mandarin and Wu, and have been assigned to one or other of these groups or treated as separate by various authors. Li Rong and the Language Atlas of China treated it as a separate top-level group, but this remains controversial.[48][49]

The Language Atlas of China calls the remainder of Mandarin a "supergroup", divided into eight dialect groups distinguished by their treatment of the Middle Chinese entering tone (see Tones below):[50]

- Northeastern Mandarin, spoken in Manchuria except the Liaodong Peninsula. This dialect is closely related to Standard Chinese, with little variation in lexicon and very few tonal differences.

- Beijing dialect in Beijing and environs such as Chengde and Hebei. The Beijing dialect forms the basis of Standard Chinese. Some people in areas of recent large-scale immigration, such as northern Xinjiang, speak the Beijing dialect or something very close to it.

- Jilu Mandarin, spoken in Hebei ("Ji") and Shandong ("Lu") provinces except the Shandong Peninsula, including Tianjin dialect. Tones and vocabulary are markedly different. In general, there is substantial intelligibility with Beijing Mandarin.

- Jiaoliao Mandarin, spoken in Shandong (Jiaodong) and Liaodong Peninsulas. Very noticeable tonal changes, different in "flavour" from Ji–Lu Mandarin, but with more variance. There is moderate intelligibility with Beijing.

- Central Plains Mandarin, spoken in Henan province, the central parts of Shaanxi in the Yellow River valley, and southern Xinjiang. There are significant phonological differences, with partial intelligibility with Beijing. The Dungan language spoken in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan belongs to this group. Dungan speakers such as the poet Iasyr Shivaza have reported being understood by speakers of the Beijing dialect, but not vice versa.[51]

- Lanyin Mandarin, spoken in Gansu province (with capital Lanzhou) and Ningxia autonomous region (with capital Yinchuan), as well as northern Xinjiang.

- Lower Yangtze Mandarin (or Jiang–Huai), spoken in the parts of Jiangsu and Anhui on the north bank of the Yangtze, as well as some areas on the south bank, such as Nanjing in Jiangsu, Jiujiang in Jiangxi, etc. There are significant phonological and lexical changes to varying degrees, and intelligibility with Beijing is limited. Lower Yangtze Mandarin has been significantly influenced by Wu Chinese.

- Southwestern Mandarin, spoken in the provinces of Hubei, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, and the Mandarin-speaking areas of Hunan, Guangxi and southern Shaanxi. There are sharp phonological, lexical, and tonal changes, and intelligibility with Beijing is limited to varying degrees.[31][32]

The Atlas also includes several unclassified Mandarin dialects spoken in scattered pockets across southeastern China, such as Nanping in Fujian and Dongfang on Hainan,[52] Another Mandarin variety of uncertain classification is apparently Gyami, recorded in the 19th century in the Tibetan foothills, who the Chinese apparently did not recognize as Chinese.[53]

Phonology

Syllables consist maximally of an initial consonant, a glide, a vowel, a final, and tone. Not every syllable that is possible according to this rule actually exists in Mandarin, as there are rules prohibiting certain phonemes from appearing with others, and in practice there are only a few hundred distinct syllables.

Phonological features that are generally shared by the Mandarin dialects include:

- the palatalization of velars and alveolar sibilants when they occur before palatal glides;

- the disappearance of final plosives and /-m/ (although in many Lower Yangtze Mandarin and Jin dialects, an echo of the final plosives is preserved as a glottal stop);

- the reduction of the six tones inherited from Middle Chinese after the tone split to four tones;

- the presence of retroflex consonants (although these are absent in many dialects of Southwestern and Northeastern Mandarin);

- the historical devoicing of plosives and sibilants (also common to most non-Mandarin varieties).

Initials

The maximal inventory of initials of a Mandarin dialect is as follows, with bracketed pinyin spellings given for those present in the standard language:[54]

| Labial | Apical | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | /p/ ⟨b⟩ | /t/ ⟨d⟩ | /k/ ⟨g⟩ | ||

| /pʰ/ ⟨p⟩ | /tʰ/ ⟨t⟩ | /kʰ/ ⟨k⟩ | |||

| Nasals | /m/ ⟨m⟩ | /n/ ⟨n⟩ | /ŋ/ | ||

| Affricates | /t͡s/ ⟨z⟩ | /ʈ͡ʂ/ ⟨zh⟩ | /t͡ɕ/ ⟨j⟩ | ||

| /t͡sʰ/ ⟨c⟩ | /ʈ͡ʂʰ/ ⟨ch⟩ | /t͡ɕʰ/ ⟨q⟩ | |||

| Fricatives | /f/ ⟨f⟩ | /s/ ⟨s⟩ | /ʂ/ ⟨sh⟩ | /ɕ/ ⟨x⟩ | /x/ ⟨h⟩ |

| Sonorants | /w/ | /l/ ⟨l⟩ | /ɻ ~ ʐ/ ⟨r⟩ | /j/ |

- Most Mandarin-speaking areas distinguish between the retroflex initials /ʈ͡ʂ ʈ͡ʂʰ ʂ/ from the apical sibilants /ts tsʰ s/, though they often have a different distribution than in the standard language. In most dialects of the southeast and southwest the retroflex initials have merged with the alveolar sibilants, so that zhi becomes zi, chi becomes ci, and shi becomes si.[55]

- The alveolo-palatal sibilants /tɕ tɕʰ ɕ/ are the result of merger between the historical palatalized velars /kj kʰj xj/ and palatalized alveolar sibilants /tsj tsʰj sj/.[55] In about 20% of dialects, the alveolar sibilants failed to palatalize, remaining separate from the alveolo-palatal initials. (The unique pronunciation used in Beijing opera falls into this category.) On the other side, in some dialects of eastern Shandong, the velar initials have failed to palatalize.

- Many southwestern Mandarin dialects mix /f/ and /xw/, substituting one for the other in some or all cases.[56] For example, fei /fei/ "to fly" and hui /xwei/ "dust" may be merged in these areas.

- In some dialects, initial /l/ and /n/ are not distinguished. In Southwestern Mandarin, these sounds usually merge to /n/; in Lower Yangtze Mandarin, they usually merge to /l/.[56]

- People in many Mandarin-speaking areas may use different initial sounds where Beijing uses initial r- /ʐ/. Common variants include /j, /l/, /n/ and /w/.[55]

- Some dialects have initial /ŋ/ corresponding to the zero initial of the standard language.[55] This initial is the result of a merger of the Middle Chinese zero initial with /ŋ/ and /ʔ/.

- Many dialects of Northwestern and Central Plains Mandarin have /pf pfʰ f v/ where Beijing has /tʂw tʂʰw ʂw ɻw/.[55] Examples include /pfu/ "pig" for standard zhū 豬 /tʂu/, /fei/ "water" for standard shuǐ 水 /ʂwei/, /vã/ "soft" for standard ruǎn 軟 /ɻwan/.

Finals

Most Mandarin dialects have three medial glides /j/, /w/ and /ɥ/ (spelled i, u and ü in pinyin), though their incidence varies. The medial /w/, is lost after apical initials in several areas.[55] Thus Southwestern Mandarin has /tei/ "right" where the standard language has dui /twei/. Southwestern Mandarin also has /kai kʰai xai/ in some words where the standard has jie qie xie /tɕjɛ tɕʰjɛ ɕjɛ/. This is a stereotypical feature of southwestern Mandarin, since it is so easily noticeable. E.g. hai "shoe" for standard xie, gai "street" for standard jie.

Mandarin dialects typically have relatively few vowels. Syllabic fricatives, as in standard zi and zhi, are common in Mandarin dialects, though they also occur elsewhere.[57] The Middle Chinese off-glides /j/ and /w/ are generally preserved in Mandarin dialects, yielding several diphthongs and triphthongs in contrast to the larger sets of monophthongs common in other dialect groups (and some widely scattered Mandarin dialects).[57]

The Middle Chinese coda /m/ was still present in Old Mandarin, but has merged with /n/ in the modern dialects.[55] In some areas (especially the southwest) final /ŋ/ has also merged with /n/. This is especially prevalent in the rhyme pairs -en/-eng /ən ɤŋ/ and -in/-ing /in iŋ/. As a result, jīn "gold" and jīng "capital" merge in those dialects.

The Middle Chinese final stops have undergone a variety of developments in different Mandarin dialects (see Tones below). In Lower Yangtze dialects and some north-western dialects they have merged as a final glottal stop. In other dialects they have been lost, with varying effects on the vowel.[55] As a result, Beijing Mandarin and Northeastern Mandarin underwent more vowel mergers than many other varieties of Mandarin. For example:

| Character | Meaning | Standard (Beijing) | Beijing, Harbin Colloquial | Jinan (Ji–Lu) | Xi'an (Central Plains) | Chengdu (Southwestern) | Yangzhou (Lower Yangtze) | Middle Chinese Reconstructed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | IPA | ||||||||

| 课 | lesson | kè | kʰɤ | kʰɤ | kʰə | kʰuo | kʰo | kʰo | kʰɑ |

| 客 | guest | tɕʰiɛ[lower-alpha 3] | kʰei | kʰei | kʰe | kʰəʔ | kʰɰak | ||

| 果 | fruit | guǒ | kwɔ | kwɔ | kwə | kwo | ko | ko | kwɑ |

| 国 | country | guó | kwe | kwe | kɔʔ | kwək | |||

R-coloring, a characteristic feature of Mandarin, works quite differently in the southwest. Whereas Beijing dialect generally removes only a final /j/ or /n/ when adding the rhotic final -r /ɻ/, in the southwest the -r replaces nearly the entire rhyme.

Tones

In general, no two Mandarin-speaking areas have exactly the same set of tone values, but most Mandarin-speaking areas have very similar tone distribution. For example, the dialects of Jinan, Chengdu, Xi'an and so on all have four tones that correspond quite well to the Beijing tones of [˥] (55), [˧˥] (35), [˨˩˦] (214), and [˥˩] (51). The exception to this rule lies in the distribution of syllables formerly ending in a stop consonant, which are treated differently in different dialects of Mandarin.[58]

Middle Chinese stops and affricates had a three-way distinction between tenuis, voiceless aspirate and voiced (or breathy voiced) consonants. In Mandarin dialects the voicing is generally lost, yielding voiceless aspirates in syllables with a Middle Chinese level tone and non-aspirates is other syllables.[36] Of the four tones of Middle Chinese, the level, rising and departing tones have also developed into four modern tones in a uniform way across Mandarin dialects: the Middle Chinese level tone has split into two registers, conditioned on voicing of the Middle Chinese initial, while rising tone syllables with voiced obstruent initials have shifted to the departing tone.[59] The following examples from the standard language illustrate the regular development common to Mandarin dialects (recall that pinyin d denotes a non-aspirate /t/, while t denotes an aspirate /tʰ/):

| Middle Chinese tone | "level tone" (píng 平) |

"rising tone" (shǎng 上) |

"departing tone" (qù 去) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | 丹 | 灘 | 蘭 | 彈 | 亶 | 坦 | 懶 | 但 | 旦 | 炭 | 爛 | 彈 | |

| Middle Chinese | tan | tʰan | lan | dan | tan | tʰan | lan | dan | tan | tʰan | lan | dan | |

| Standard Chinese | dān | tān | lán | tán | dǎn | tǎn | lǎn | dàn | dàn | tàn | làn | dàn | |

| Modern Mandarin tone | 1 (yīn píng) | 2 (yáng píng) | 3 (shǎng) | 4 (qù) | |||||||||

In traditional Chinese phonology, syllables that ended in a stop in Middle Chinese (i.e. /p/, /t/ or /k/) were considered to belong to a special category known as the "entering tone". These final stops have disappeared in most Mandarin dialects, with the syllables distributed over the other four modern tones in different ways in the various Mandarin subgroups. In the Beijing dialect that underlies the standard language, syllables beginning with original voiceless consonants were redistributed across the four tones in a completely random pattern.[60] For example, the three characters 积脊迹, all tsjek in Middle Chinese (William H. Baxter's transcription), are now pronounced jī, jǐ and jì respectively. Older dictionaries such as Mathews' Chinese-English Dictionary mark characters whose pronunciation formerly ended with a plosive with a superscript 5; however, this tone number is more commonly used for syllables that always have a neutral tone (see below).

In Lower Yangtze dialects, a minority of Southwestern dialects (e.g. Minjiang) and Jin (sometimes considered non-Mandarin), former final plosives were not deleted entirely, but were reduced to a glottal stop /ʔ/.[60] This development is shared with the non-Mandarin Wu dialects, and is thought to represent the pronunciation of Old Mandarin. In line with traditional Chinese phonology, dialects such as Lower Yangtze and Minjiang are thus said to have five tones instead of four. However, modern linguistics considers these syllables as having no phonemic tone at all.

| subgroup | Middle Chinese initial | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| voiceless | voiced sonorant | voiced obstruent | |

| Beijing | 1,3,4 | 4 | 2 |

| Northeastern | |||

| Jiao–Liao | 3 | ||

| Ji–Lu | 1 | ||

| Central Plains | 1 | ||

| Lan–Yin | 4 | ||

| Southwestern | 2 | ||

| Lower Yangtze | marked with final glottal stop (rù) | ||

Although the system of tones is common across Mandarin dialects, their realization as tone contours varies widely:[62]

| Tone name | 1 (yīn píng) | 2 (yáng píng) | 3 (shǎng) | 4 (qù) | marked with glottal stop (rù) | |

| Beijing | Beijing | ˥ (55) | ˧˥ (35) | ˨˩˦ (214) | ˥˩ (51) | |

| Northeastern | Harbin | ˦ (44) | ˨˦ (24) | ˨˩˧ (213) | ˥˨ (52) | |

| Jiao–Liao | Yantai | ˧˩ (31) | (˥ (55)) | ˨˩˦ (214) | ˥ (55) | |

| Ji–Lu | Tianjin | ˨˩ (21) | ˧˥ (35) | ˩˩˧ (113) | ˥˧ (53) | |

| Shijiazhuang | ˨˧ (23) | ˥˧ (53) | ˥ (55) | ˧˩ (31) | ||

| Central Plains | Zhengzhou | ˨˦ (24) | ˦˨ (42) | ˥˧ (53) | ˧˩˨ (312) | |

| Luoyang | ˧˦ (34) | ˦˨ (42) | ˥˦ (54) | ˧˩ (31) | ||

| Xi'an | ˨˩ (21) | ˨˦ (24) | ˥˧ (53) | ˦ (44) | ||

| Tianshui | ˩˧ (13) | ˥˧ (53) | ˨˦ (24) | |||

| Lan–Yin | Lanzhou | ˧˩ (31) | ˥˧ (53) | ˧ (33) | ˨˦ (24) | |

| Yinchuan | ˦ (44) | ˥˧ (53) | ˩˧ (13) | |||

| Southwestern | Chengdu | ˦ (44) | ˨˩ (21) | ˥˧ (53) | ˨˩˧ (213) | |

| Xichang | ˧ (33) | ˥˨ (52) | ˦˥ (45) | ˨˩˧ (213) | ˧˩ʔ (31) | |

| Kunming | ˦ (44) | ˧˩ (31) | ˥˧ (53) | ˨˩˨ (212) | ||

| Wuhan | ˥ (55) | ˨˩˧ (213) | ˦˨ (42) | ˧˥ (35) | ||

| Liuzhou | ˦ (44) | ˧˩ (31) | ˥˧ (53) | ˨˦ (24) | ||

| Lower Yangtze | Yangzhou | ˧˩ (31) | ˧˥ (35) | ˦˨ (42) | ˥ (55) | ˥ʔ (5) |

| Nantong | ˨˩ (21) | ˧˥ (35) | ˥ (55) | ˦˨ (42), ˨˩˧ (213)* | ˦ʔ (4), ˥ʔ (5)* | |

* Dialects in and around the Nantong area typically have many more than 4 tones, due to influence from the neighbouring Wu dialects.

Mandarin dialects frequently employ neutral tones in the second syllables of words, creating syllables whose tone contour is so short and light that it is difficult or impossible to discriminate. These atonal syllables also occur in non-Mandarin dialects, but in many southern dialects the tones of all syllables are made clear.[60]

Vocabulary

There are more polysyllabic words in Mandarin than in all other major varieties of Chinese except Shanghainese. This is partly because Mandarin has undergone many more sound changes than have southern varieties of Chinese, and has needed to deal with many more homophones. New words have been formed by adding affixes such as lao- (老), -zi (子), -(e)r (儿/兒), and -tou (头/頭), or by compounding, e.g. by combining two words of similar meaning as in cōngmáng (匆忙), made from elements meaning "hurried" and "busy". A distinctive feature of southwestern Mandarin is its frequent use of noun reduplication, which is hardly used in Beijing. In Sichuan, one hears baobao "handbag" where Beijing uses bao'r. There are also a small number of words that have been polysyllabic since Old Chinese, such as húdié (蝴蝶) "butterfly".

The singular pronouns in Mandarin are wǒ (我) "I", nǐ (你 or 妳) "you", nín (您) "you (formal)", and tā (他, 她 or 它) "he/she/it", with -men (们們) added for the plural. Further, there is a distinction between the plural first-person pronoun zánmen (咱们/咱們), which is inclusive of the listener, and wǒmen (我们/我們), which may be exclusive of the listener. Dialects of Mandarin agree with each other quite consistently on these pronouns. While the first and second person singular pronouns are cognate with forms in other varieties of Chinese, the rest of the pronominal system is a Mandarin innovation (e.g., Shanghainese has non 侬/儂 "you" and yi 伊 "he/she").[63]

Because of contact with Mongolian and Manchurian peoples, Mandarin (especially the Northeastern varieties) has some loanwords from these languages not present in other varieties of Chinese, such as hútòng (胡同) "alley". Southern Chinese varieties have borrowed from Tai,[64] Austroasiatic,[65] and Austronesian languages.

In general, the greatest variation occurs in slang, in kinship terms, in names for common crops and domesticated animals, for common verbs and adjectives, and other such everyday terms. The least variation occurs in "formal" vocabulary—terms dealing with science, law, or government.

Grammar

Chinese varieties of all periods have traditionally been considered prime examples of analytic languages, relying on word order and particles instead of inflection or affixes to provide grammatical information such as person, number, tense, mood, or case. Although modern varieties, including the Mandarin dialects, use a small number of particles in a similar fashion to suffixes, they are still strongly analytic.[66]

The basic word order of subject–verb–object is common across Chinese dialects, but there are variations in the order of the two objects of ditransitive sentences. In northern dialects the indirect object precedes the direct object (as in English), for example in the Standard Chinese sentence:

我 给 你 一本 书 。 wǒ gěi nǐ yìběn shū. I give you a (one) book.

In southern dialects, as well as many southwestern and Lower Yangtze dialects, the objects occur in the reverse order.[67][68]

Most varieties of Chinese use post-verbal particles to indicate aspect, but the particles used vary. Most Mandarin dialects use the particle -le (了) to indicate the perfective aspect and -zhe (着/著) for the progressive aspect. Other Chinese varieties tend to use different particles, e.g. Cantonese jo2 咗 and gan2 紧/緊 respectively. The experiential aspect particle -guo (过/過) is used more widely, except in Southern Min.[69]

The subordinative particle de (的) is characteristic of Mandarin dialects.[70] Some southern dialects, and a few Lower Yangtze dialects, preserve an older pattern of subordination without a marking particle, while in others a classifier fulfils the role of the Mandarin particle.[71]

Especially in conversational Chinese, sentence-final particles alter the inherent meaning of a sentence. Like much vocabulary, particles can vary a great deal with regards to the locale. For example, the particle ma (嘛), which is used in most northern dialects to denote obviousness or contention, is replaced by yo (哟) in southern usage.

See also

- Chinese dictionary

- Transcription into Chinese characters

- Written Chinese

- List of languages by number of native speakers

Notes

- ↑ A folk etymology deriving the name from Mǎn dà rén (满大人 "Manchu big man") is without foundation.[6]

- ↑ For example:

- In the early 1950s, only 54% of people in the Mandarin-speaking area could understand Standard Chinese, which was based on the Beijing dialect.[29]

- "Hence we see that even Mandarin includes within it an unspecified number of languages, very few of which have ever been reduced to writing, that are mutually unintelligible."[30]

- "the common term assigned by linguists to this group of languages implies a certain homogeneity which is more likely to be related to the sociopolitical context than to linguistic reality, since most of those varieties are not mutually intelligible."[31]

- "A speaker of only standard Mandarin might take a week or two to comprehend even simple Kunminghua with ease—and then only if willing to learn it."[32]

- ↑ The development is purely due to the preservation of an early glide which later became /j/ and triggered patalization, and does not indicate the absence of a vowel merger.

References

- ↑ "Världens 100 största språk 2010" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2010), in Nationalencyklopedin

- ↑ 台灣手語簡介 (Taiwan) (2009)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Mandarin Chinese". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Mathew Ricci.

- ↑ "mandarin", Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. 1 (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2.

- ↑ Razfar & Rumenapp (2013), p. 293.

- ↑ Coblin (2000), p. 537.

- 1 2 Norman (1988), p. 136.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 181.

- 1 2 3 Wurm et al. (1987).

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 49–51.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 34–36, 52–54.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 111–132.

- ↑ Ramsey (1987), p. 10.

- ↑ Fourmont, Etienne (1742). Linguae Sinarum Mandarinicae hieroglyphicae grammatica duplex, latinè, & cum characteribus Sinensium.

- ↑ Coblin (2000), p. 539.

- ↑ Kaske (2008), pp. 48–52.

- ↑ Coblin (2003), p. 353.

- ↑ Morrison, Robert (1815). A dictionary of the Chinese language: in three parts, Volume 1. P.P. Thoms. p. x. OCLC 680482801.

- ↑ Coblin (2000), pp. 540–541.

- ↑ Ramsey (1987), pp. 3–15.

- ↑ Chen (1999), pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Zhang & Yang (2004).

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 183–190.

- ↑ Ramsey (1987), p. 22.

- ↑ Chen (1999), p. 27.

- ↑ Mair (1991), p. 18.

- 1 2 Escure (1997), p. 144.

- 1 2 Blum (2001), p. 27.

- ↑ Richards (2003), pp. 138–139.

- 1 2 3 Ramsey (1987), p. 21.

- ↑ Ramsey (1987), pp. 215–216.

- 1 2 3 4 Norman (1988), p. 191.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 36–41.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), p. 49.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 181, 191.

- ↑ Yan (2006), p. 61.

- ↑ Ting (1991), p. 190.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 55–56, 74–75.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 190.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 41–46.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), p. 55.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Yan (2006), pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), p. 75.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakoff Dyer (1977–78), p. 351.

- ↑ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Mair (1990), pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 139–141, 192.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Norman (1988), p. 193.

- 1 2 Norman (1988), p. 192.

- 1 2 Norman (1988), p. 194.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 194–196.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 194–195.

- 1 2 3 Norman (1988), p. 195.

- ↑ Li Rong's 1985 article on Mandarin classification, quoted in Yan (2006), p. 61 and Kurpaska (2010), p. 89.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 195–196.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 182, 195–196.

- ↑ Ramsey (1987), pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Norman, Jerry; Mei, Tsu-lin (1976). "The Austroasiatics in ancient South China: some lexical evidence". Monumenta Serica. 32: 274–301.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 10.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 162.

- ↑ Yue (2003), pp. 105–106.

- ↑ Yue (2003), pp. 90–93.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 196.

- ↑ Yue (2003), pp. 113–115.

- Works cited

- Blum, Susan Debra (2001), Portraits of "primitives": Ordering human kinds in the Chinese nation, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-7425-0092-1.

- Chen, Ping (1999), Modern Chinese: History and sociolinguistics, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-64572-0.

- Coblin, W. South (2000), "A brief history of Mandarin", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 120 (4): 537–552, doi:10.2307/606615, JSTOR 606615.

- —— (2003), "Robert Morrison and the Phonology of Mid-Qīng Mandarin", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, 13 (3): 339–355, doi:10.1017/S1356186303003134.

- Escure, Geneviève (1997), Creole and dialect continua: standard acquisition processes in Belize and China (PRC), John Benjamins, ISBN 978-90-272-5240-1.

- Kaske, Elisabeth (2008), The politics of language in Chinese education, 1895–1919, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-16367-6.

- Kurpaska, Maria (2010), Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of "The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects", Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-021914-2.

- Mair, Victor H. (1990), "Who were the Gyámi?" (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, 18 (b): 1–8. (Archive)

- —— (1991), "What Is a Chinese "Dialect/Topolect"? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic terms" (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, 29: 1–31.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Razfar, Aria; Rumenapp, Joseph C. (2013), Applying Linguistics in the Classroom: A Sociocultural Approach, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-21205-5.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The Languages of China, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-01468-5.

- Richards, John F. (2003), The unending frontier: an environmental history of the early modern world, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-23075-0.

- Rimsky-Korsakoff Dyer, Svetlana (1977–78), "Soviet Dungan nationalism: a few comments on their origin and language", Monumenta Serica, 33: 349–362, JSTOR 40726247.

- Ting, Pang-Hsin (1991), "Some theoretical issues in the study of Mandarin dialects", in Wang, William S-Y., Language and Dialects of China, Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series, 3, pp. 185–234, JSTOR 23827039.

- Wurm, Stephen Adolphe; Li, Rong; Baumann, Theo; Lee, Mei W. (1987), Language Atlas of China, Longman, ISBN 978-962-359-085-3.

- Yan, Margaret Mian (2006), Introduction to Chinese Dialectology, LINCOM Europa, ISBN 978-3-89586-629-6.

- Yue, Anne O. (2003), "Chinese dialects: grammar", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.), The Sino-Tibetan languages, Routledge, pp. 84–125, ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1.

- Zhang, Bennan; Yang, Robin R. (2004), "Putonghua education and language policy in postcolonial Hong Kong", in Zhou, Minglang (ed.), Language policy in the People's Republic of China: theory and practice since 1949, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 143–161, ISBN 978-1-4020-8038-8.

Further reading

- Dwyer, Arienne M. (1995), "From the Northwest China Sprachbund: Xúnhuà Chinese dialect data", Yuen Ren Society Treasury of Chinese Dialect Data, 1: 143–182.

- Novotná, Zdenka (1967), "Contributions to the Study of Loan-Words and Hybrid Words in Modern Chinese", Archiv Orientální, 35: 613–649.

- Shen, Zhongwei 沈钟伟 (2011), "The origin of Mandarin", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 39 (2): 1–31.

Historical Western language texts

- Balfour, Frederic Henry (1883), Idiomatic Dialogues in the Peking Colloquial for the Use of Student, Shanghai: Offices of the North-China Herald.

- Grainger, Adam (1900), Western Mandarin: or the spoken language of western China, with syllabic and English indexes, Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press.

- MacGillivray, Donald (1905), A Mandarin-Romanized dictionary of Chinese, Shanghai: Presbyterian Mission Press.

- Mateer, Calvin Wilson (1906), A course of Mandarin lessons, based on idiom (revised 2nd ed.), Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press.

- Meigs, F.E. (1904), The Standard System of Mandarin Romanization: Introduction, Sound Table an Syllabary, Shanghai: Educational Association of China.

- Meigs, F.E. (1905), The Standard System of Mandarin Romanization: Radical Index, Shanghai: Educational Association of China.

- Stent, George Carter; Hemeling, Karl (1905), A Dictionary from English to Colloquial Mandarin Chinese, Shanghai: Statistical Department of the Inspectorate General of Customs.

- Whymant, A. Neville J. (1922), Colloquial Chinese (northern) (2nd ed.), London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company.

External links

| Library resources about Mandarin Chinese |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mandarin Chinese. |

- Tones in Mandarin Dialects : Comprehensive tone comparison charts for 523 Mandarin dialects. (Compiled by James Campbell) – Internet Archive mirror

.svg.png)