Kali

| Kali | |

|---|---|

| Goddess of Time, Creation, Destruction and Power | |

|

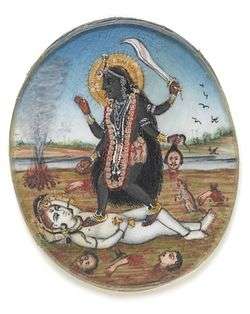

Dakshinakali, a benign form of Kali | |

| Devanagari | काली |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Kālī |

| Affiliation | Devi, Parvati, Durga, Mahakali, Mahavidya, Tara, Chhinnamasta |

| Abode | Cremation grounds (but varies by interpretation) |

| Mantra | Oṃ jayantī mangala kālī bhadrakālī kapālinī. Durgā ksamā śivā dhātrī svāhā svadhā namō'stutē |

| Weapon | Scimitar |

| Consort | Shiva |

| Mount | Lion |

| Region | Kashmir, Kerala, South India, Bengal, and Assam |

| Festivals | Kali Puja |

Kālī (/ˈkɑːli/; Sanskrit: काली), also known as Kālikā (Sanskrit: कालिका), is a Hindu goddess. Kali is one of the ten Mahavidyas, a list which combines Sakta and Buddhist goddesses.[1]

Kali's earliest appearance is that of a destroyer principally of evil forces. She is the goddess of one of the four subcategories of the Kulamārga, a category of tantric Saivism.[2] Over time, she has been worshipped by devotional movements and tantric sects variously as the Divine Mother, Mother of the Universe, Adi Shakti, or Adi Parashakti.[3][4][5] Shakta Hindu and Tantric sects additionally worship her as the ultimate reality or Brahman.[6] She is also seen as divine protector and the one who bestows moksha, or liberation.[3] Kali is often portrayed standing or dancing on her consort, the Hindu god Shiva, who lies calm and prostrate beneath her. Kali is worshipped by Hindus throughout India.[7]

Etymology

Kālī is the feminine form of kālam ("black, dark coloured").[8] Kālī also shares the meaning of "time" or "the fullness of time" with the masculine noun "kāla"—and by extension, time as "changing aspect of nature that bring things to life or death." Other names include Kālarātri ("the black night"), and Kālikā ("the black one").[9]

The homonymous kāla, "appointed time", which depending on context can mean "death", is distinct from kāla "black", but became associated through popular etymology. The association is seen in a passage from the Mahābhārata, depicting a female figure who carries away the spirits of slain warriors and animals. She is called kālarātri (which Thomas Coburn, a historian of Sanskrit Goddess literature, translates as "night of death") and also kālī (which, as Coburn notes, can be read here either as a proper name or as a description "the black one").[9] Kālī is also the feminine form of Kāla, an epithet of Shiva, and thus the consort of Shiva.[10]

Origins

Hugh Urban notes that although the word Kālī appears as early as the Atharva Veda, the first use of it as a proper name is in the Kathaka Grhya Sutra (19.7).[11] Kali appears in the Mundaka Upanishad (section 1, chapter 2, verse 4) not explicitly as a goddess, but as the black tongue of the seven flickering tongues of Agni, the Hindu god of fire.[9]

According to David Kinsley, Kāli is first mentioned in Hindu tradition as a distinct goddess around 600 CE, and these texts "usually place her on the periphery of Hindu society or on the battlefield."[12] She is often regarded as the Shakti of Shiva, and is closely associated with him in various Puranas.

Her most well known appearance on the battlefield is in the sixth century Devi Mahatmyam. Two demons, Chanda and Munda attack the goddess Durga. Durga responds with such anger that her face turns dark and Kali appears out of her forehead. Kali's appearance is black, gaunt with sunken eyes, and wearing a tiger skin and a garland of human heads. She immediately defeats the two demons. Later in the same battle, the demon Raktabija is undefeated because of his ability to reproduce himself from every drop of his blood that reaches the ground. Countless Raktabija clones appear on the battlefield. Kali eventually defeats him by sucking his blood before it can reach the ground, and eating the numerous clones. Kinsley writes that Kali represents "Durga's personified wrath, her embodied fury."[12]

Other origin stories involve Parvati and Shiva. Parvati is typically portrayed as a benign and friendly goddess. The Linga Purana describes Shiva asking Parvati to defeat the demon Daruka, who received a boon that would only allow a female to kill him. Parvati merges with Shiva's body, reappearing as Kali to defeat Daruka and his armies. Her bloodlust gets out of control, only calming when Shiva intervenes. The Vamana Purana has a different version of Kali's relationship with Parvati. When Shiva addresses Parvati as Kali, "the black one," she is greatly offended. Parvati performs austerities to lose her dark complexion and becomes Gauri, the golden one. Her dark sheath becomes Kausiki, who while enraged, creates Kali.[12] Regarding the relationship between Kali, Parvati, and Shiva, Kinsley writes that:

In relation to Siva, she [Kali] appears to play the opposite role from that of Parvati. Parvati calms Siva, counterbalancing his antisocial or destructive tendencies; she brings him within the sphere of domesticity and with her soft glances urges him to moderate the destructive aspects of his tandava dance. Kali is Shiva's "other wife," as it were, provoking him and encouraging him in his mad, antisocial, disruptive habits. It is never Kali who tames Siva, but Siva who must calm Kali.[12]

Legends

Kāli appears in the Sauptika Parvan of the Mahabharata (10.8.64). She is called Kālarātri (literally, "black night") and appears to the Pandava soldiers in dreams, until finally she appears amidst the fighting during an attack by Drona's son Ashwatthama.

Another story involving Kali is her escapade with a band of thieves. The thieves wanted to make a human sacrifice to Kali, and unwisely chose a saintly Brahmin monk as their victim. The radiance of the young monk was so much that it burned the image of Kali, who took living form and killed the entire band of thieves, decapitating them and drinking their blood.[12]

Slayer of Raktabija

In Kāli's most famous legend, Durga and her assistants, the Matrikas, wound the demon Raktabija, in various ways and with a variety of weapons in an attempt to destroy him. They soon find that they have worsened the situation for with every drop of blood that is dripped from Raktabija he reproduces a clone of himself. The battlefield becomes increasingly filled with his duplicates.[13] Durga summons Kāli to combat the demons. The Devi Mahatmyam describes:

Out of the surface of her (Durga's) forehead, fierce with frown, issued suddenly Kali of terrible countenance, armed with a sword and noose. Bearing the strange khatvanga (skull-topped staff ), decorated with a garland of skulls, clad in a tiger's skin, very appalling owing to her emaciated flesh, with gaping mouth, fearful with her tongue lolling out, having deep reddish eyes, filling the regions of the sky with her roars, falling upon impetuously and slaughtering the great asuras in that army, she devoured those hordes of the foes of the devas.[14]

Kali consumes Raktabija and his duplicates, and dances on the corpses of the slain.[13] In the Devi Mahatmya version of this story, Kali is also described as a Matrika and as a Shakti or power of Devi. She is given the epithet Cāṃuṇḍā (Chamunda), i.e. the slayer of the demons Chanda and Munda.[15] Chamunda is very often identified with Kali and is very much like her in appearance and habit.[16]

Iconography and forms

.jpg)

Kali is portrayed mostly in two forms: the popular four-armed form and the ten-armed Mahakali form. In both of her forms, she is described as being black in colour but is most often depicted as blue in popular Indian art. Her eyes are described as red with intoxication, and in absolute rage, her hair is shown disheveled, small fangs sometimes protrude out of her mouth, and her tongue is lolling. She is often shown naked or just wearing a skirt made of human arms and a garland of human heads. She is also accompanied by serpents and a jackal while standing on the calm and prostrate Shiva, usually right foot forward to symbolize the more popular Dakshinamarga or right-handed path, as opposed to the more infamous and transgressive Vamamarga or left-handed path.[17]

In the ten-armed form of Mahakali she is depicted as shining like a blue stone. She has ten faces, ten feet, and three eyes for each head. She has ornaments decked on all her limbs. There is no association with Shiva.[18]

The Kalika Purana describes Kali as possessing a soothing dark complexion, as perfectly beautiful, riding a lion, four-armed, holding a sword and blue lotuses, her hair unrestrained, body firm and youthful.[19]

In spite of her seemingly terrible form, Kali Ma is often considered the kindest and most loving of all the Hindu goddesses, as she is regarded by her devotees as the Mother of the whole Universe. And because of her terrible form, she is also often seen as a great protector. When the Bengali saint Ramakrishna once asked a devotee why one would prefer to worship Mother over him, this devotee rhetorically replied, "Maharaj, when they are in trouble your devotees come running to you. But, where do you run when you are in trouble?"[20][21]

Popular form

Classic depictions of Kali share several features, as follows:

Kali's most common four armed iconographic image shows each hand carrying variously a sword, a trishul (trident), a severed head, and a bowl or skull-cup (kapala) catching the blood of the severed head.

Two of these hands (usually the left) are holding a sword and a severed head. The sword signifies divine knowledge and the human head signifies human ego which must be slain by divine knowledge in order to attain moksha. The other two hands (usually the right) are in the abhaya (fearlessness) and varada (blessing) mudras, which means her initiated devotees (or anyone worshipping her with a true heart) will be saved as she will guide them here and in the hereafter.[22]

She has a garland consisting of human heads, variously enumerated at 108 (an auspicious number in Hinduism and the number of countable beads on a japa mala or rosary for repetition of mantras) or 51, which represents Varnamala or the Garland of letters of the Sanskrit alphabet, Devanagari. Hindus believe Sanskrit is a language of dynamism, and each of these letters represents a form of energy, or a form of Kali. Therefore, she is generally seen as the mother of language, and all mantras.[23]

She is often depicted naked which symbolizes her being beyond the covering of Maya since she is pure (nirguna) being-consciousness-bliss and far above prakriti. She is shown as very dark as she is brahman in its supreme unmanifest state. She has no permanent qualities—she will continue to exist even when the universe ends. It is therefore believed that the concepts of color, light, good, bad do not apply to her[24]

Mahakali

Mahakali (Sanskrit: Mahākālī, Devanagari: महाकाली), literally translated as Great Kali, is sometimes considered as a greater form of Kali, identified with the Ultimate reality of Brahman. It can also be used as an honorific of the Goddess Kali,[25] signifying her greatness by the prefix "Mahā-". Mahakali, in Sanskrit, is etymologically the feminized variant of Mahakala or Great Time (which is interpreted also as Death), an epithet of the God Shiva in Hinduism. Mahakali is the presiding Goddess of the first episode of the Devi Mahatmya. Here she is depicted as Devi in her universal form as Shakti. Here Devi serves as the agent who allows the cosmic order to be restored.

Kali is depicted in the Mahakali form as having ten heads, ten arms, and ten legs. Each of her ten hands is carrying a various implement which vary in different accounts, but each of these represent the power of one of the Devas or Hindu Gods and are often the identifying weapon or ritual item of a given Deva. The implication is that Mahakali subsumes and is responsible for the powers that these deities possess and this is in line with the interpretation that Mahakali is identical with Brahman. While not displaying ten heads, an "ekamukhi" or one headed image may be displayed with ten arms, signifying the same concept: the powers of the various Gods come only through Her grace.

Daksinakali

Daksinakali, also spelled Dakshinakali, is the most popular form of Kali in Bengal.[26] There are various versions for the origin of the name Dakshinakali. Dakshina refers to the gift given to a priest before performing a ritual or to one's guru. Such gifts are traditionally given with the right hand. Daksinakali's two right hands are usually depicted in gestures of blessing and giving of boons. One version of the origin of her name comes from the story of Yama, lord of death, who lives in the south (daksina). When Yama heard Kali's name, he fled in terror, and so those who worship Kali are said to be able to overcome death itself.[27][28]

Daksinakali is typically shown with her right foot on Shiva's chest—while depictions showing Kali with her left foot on Shiva's chest depict the even more fearsome Vamakali. The pose shows the conclusion of an episode in which Kali was rampaging out of control after destroying many demons. Shiva, fearing that Kali would not stop until she destroyed the world, could only think of one way to pacify her. He lay down on the battlefield so that she would have to step on him. Seeing her consort under her foot, Kali realized that she had gone too far, and calmed down. In some interpretations of the story, Shiva was attempting to receive Kali's grace by receiving her foot on his chest.[29]

There are many different interpretations of the pose held by Dakshinakali, including those of the 18th and 19th century bhakti poet-devotees such as Ramprasad Sen. Most have to do with battle imagery and tantric metaphysics. The most popular however is a devotional view. According to Rachel Fell McDermott, the poets portrayed Siva as "the devotee who falls at [Kali's] feet in devotion, or in surrender of his ego, or in hopes of gaining moksha by her touch. In fact, Siva is said to have become so enchanted by Kali that he performed austerities to win her, and having received the treasure of her feet, held them against his heart in reverence.[30]

The growing popularity of worship of a more benign form of Kali, as Daksinakali, is often attributed to Krishnananda Agamavagisha. He was a noted Bengali leader of the 17th century, author of a Tantra encyclopedia called Tantrasara. Kali appeared to him in a dream and told him to popularize her in a particular form that would appear to him the following day. The next morning he observed a young woman making cow dung patties. While placing a patty on a wall, she stood in the alidha pose, with her right foot forward. When she saw Krishnananda watching her, she was embarrassed and put her tongue between her teeth. Krishnananada took his previous worship of Kali out of the cremation grounds and into a more domestic setting.[31][28] Krishnananda Vagamavagisha was also the guru of the Kali devotee and poet Ramprasad Sen.[32]

Shamshan Kali

If the Kali steps out with the left foot and holds the sword in her right hand, she is the terrible form of Mother, the Shamshan Kali of the cremation ground.She is worshiped by tantrics, the followers of Tantra, who believe that one's spiritual discipline practised in a smashan (cremation ground) brings success quickly.[33] A well known Shamshan Kali can be found in Barabelun, located in Bardhaman District of West Bengal. Known as "Boro-Ma" or the Big Mother, this Kali is estimated to be over 550 years old. The 24 foot high idol is worshipped and revered by the masses.[34]

Symbolism

There are many different interpretations of the symbolic meanings of Kali's depiction, depending on a Tantric or devotional approach, and on whether one views her image symbolically, allegorically, or mystically.[27]

Physical form

There are many varied depictions of the different forms of Kali. The most common shows her with four arms and hands, showing aspects of creation and destruction. The two right hands are often held out in blessing, one in a mudra saying "fear not" (abhayamudra), the other conferring boons. Her left hands hold a severed head and blood-covered sword. The sword severs the bondage of ignorance and ego, represented by the severed head. One interpretation of Kali's tongue is that the red tongue symbolizes the rajasic nature being conquered by the white (symbolizing sattvic) nature of the teeth. Her blackness represents that she is nirguna, beyond all qualities of nature, and transcendent.[27][28]

The most widespread interpretation of Kali's extended tongue involve her embarrassment over the sudden realization that she has stepped on her husband's chest. Kali's sudden "modesty and shame" over that act is the prevalent interpretation among Oriya Hindus.[28] The biting of the tongue conveys the emotion of lajja or modesty, an expression that is widely accepted as the emotion being expressed by Kali.[35][38] In Bengal also, Kali's protruding tongue is "widely accepted... as a sign of speechless embarrassment: a gesture very common among Bengalis."[36][39]

Kali is often shown standing with her right foot on Shiva's chest. This represents an episode where Kali was out of control on the battlefield, such that she was about to destroy the entire universe. Shiva pacified her by laying down under her foot, both to receive her blessing, but also to pacify and calm her. Shiva is sometimes shown with a blissful smile on his face.[28] She is typically shown with a garland of severed heads, often numbering fifty. This can symbolize the letters of the Sanskrit alphabet and therefore as the primordial sound of Aum from which all creation proceeds. The severed arms which make up her skirt represent her devotee's karma that she has taken on.[27]

Mother Nature

The name Kali means Kala or force of time. When there were neither the creation, nor the sun, the moon, the planets, and the earth, there was only darkness and everything was created from the darkness. The Dark appearance of Kali represents the darkness from which everything was born.[33] Her complexion is deep blue, like the sky and ocean water as blue. As she is also the goddess of Preservation Kali is worshiped as mother to preserve the nature. Kali is standing calm on Shiva ,her appearance represents the preservation of mother nature. Her free, long and black hair represents nature's freedom from civilization. Under the third eye of kali, the signs of both sun, moon and fire are visible which represent the driving forces of nature.Kali is not always thought of as a Dark Goddess. Despite Kali's origins in battle, She evolved to a full-fledged symbol of Mother Nature in Her creative, nurturing and devouring aspects. She is referred to as a great and loving primordial Mother Goddess in the Hindu tantric tradition. In this aspect, as Mother Goddess, She is referred to as Kali Ma, meaning Kali Mother, and millions of Hindus revere Her as such.[40]

Shiva in Kali iconography

There are several interpretations of the symbolism behind the commonly represented image of Kali standing on Shiva's supine form. A common one is that Shiva symbolizes purusha, the universal unchanging aspect of reality, or pure consciousness. Kali represents Prakriti, nature or matter, sometimes seen as having a feminine quality. The merging of these two qualities represent ultimate reality.[41]

A tantric interpretation sees Shiva as consciousness and Kali as power or energy. Consciousness and energy are dependent upon each other, since Shiva depends on Shakti, or energy, in order to fulfill his role in creation, preservation, and destruction. In this view, without Shakti, Shiva is a corpse — unable to act.[42]

Worship

Mantra

Kali could be considered a general concept, like Durga, and is mostly worshiped in the Kali Kula sect of worship. The closest way of direct worship is Maha Kali or Bhadrakali (Bhadra in Sanskrit means 'gentle'). Kali is worshiped as one of the 10 Mahavidya forms of Adi Parashakti. One mantra for worship is:

ॐ जयंती मंगल काली भद्रकाली कपालिनी । दुर्गा शिवा क्षमा धात्री स्वाहा स्वधा नमोऽस्तुते ॥

(Sarvamaṅgalamāṅgalyē śivē sarvārthasādhikē . śaraṇyē tryambakē gauri nārāyaṇi namō'stu tē.

Tantra

Goddesses play an important role in the study and practice of Tantra Yoga, and are affirmed to be as central to discerning the nature of reality as are the male deities. Although Parvati is often said to be the recipient and student of Shiva's wisdom in the form of Tantras, it is Kali who seems to dominate much of the Tantric iconography, texts, and rituals. In many sources Kāli is praised as the highest reality or greatest of all deities. The Nirvana-tantra says the gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva all arise from her like bubbles in the sea, ceaselessly arising and passing away, leaving their original source unchanged. The Niruttara-tantra and the Picchila-tantra declare all of Kāli's mantras to be the greatest and the Yogini-tantra, Kamakhya-tantra and the Niruttara-tantra all proclaim Kāli vidyas (manifestations of Mahadevi, or "divinity itself"). They declare her to be an essence of her own form (svarupa) of the Mahadevi.[44]

In the Mahanirvana-tantra, Kāli is one of the epithets for the primordial sakti, and in one passage Shiva praises her:

At the dissolution of things, it is Kāla [Time] Who will devour all, and by reason of this He is called Mahākāla [an epithet of Lord Shiva], and since Thou devourest Mahākāla Himself, it is Thou who art the Supreme Primordial Kālika. Because Thou devourest Kāla, Thou art Kāli, the original form of all things, and because Thou art the Origin of and devourest all things Thou art called the Adya [the Primordial One]. Re-assuming after Dissolution Thine own form, dark and formless, Thou alone remainest as One ineffable and inconceivable. Though having a form, yet art Thou formless; though Thyself without beginning, multiform by the power of Maya, Thou art the Beginning of all, Creatrix, Protectress, and Destructress that Thou art.[44]

The figure of Kāli conveys death, destruction, and the consuming aspects of reality. As such, she is also a "forbidden thing", or even death itself. In the Pancatattva ritual, the sadhaka boldly seeks to confront Kali, and thereby assimilates and transforms her into a vehicle of salvation.[44] This is clear in the work of the Karpuradi-stotra,[45] a short praise of Kāli describing the Pancatattva ritual unto her, performed on cremation grounds. (Samahana-sadhana)

He, O Mahākāli who in the cremation-ground, naked, and with dishevelled hair, intently meditates upon Thee and recites Thy mantra, and with each recitation makes offering to Thee of a thousand Akanda flowers with seed, becomes without any effort a Lord of the earth. Oh Kāli, whoever on Tuesday at midnight, having uttered Thy mantra, makes offering even but once with devotion to Thee of a hair of his Shakti [his energy/female companion] in the cremation-ground, becomes a great poet, a Lord of the earth, and ever goes mounted upon an elephant.[44]

The Karpuradi-stotra, dated to approximately 10th century ACE,[46] clearly indicates that Kāli is more than a terrible, vicious, slayer of demons who serves Durga or Shiva. Here, she is identified as the supreme mother of the universe, associated with the five elements. In union with Lord Shiva, she creates and destroys worlds. Her appearance also takes a different turn, befitting her role as ruler of the world and object of meditation.[47] In contrast to her terrible aspects, she takes on hints of a more benign dimension. She is described as young and beautiful, has a gentle smile, and makes gestures with her two right hands to dispel any fear and offer boons. The more positive features exposed offer the distillation of divine wrath into a goddess of salvation, who rids the sadhaka of fear. Here, Kali appears as a symbol of triumph over death.[48]

Bengali tradition

Kali is also a central figure in late medieval Bengali devotional literature, with such devotees as Ramprasad Sen (1718–75). With the exception of being associated with Parvati as Shiva's consort, Kāli is rarely pictured in Hindu legends and iconography as a motherly figure until Bengali devotions beginning in the early eighteenth century. Even in Bengāli tradition her appearance and habits change little, if at all.[49]

The Tantric approach to Kāli is to display courage by confronting her on cremation grounds in the dead of night, despite her terrible appearance. In contrast, the Bengali devotee appropriates Kāli's teachings adopting the attitude of a child, coming to love her unreservedly. In both cases, the goal of the devotee is to become reconciled with death and to learn acceptance of the way that things are. These themes are well addressed in Rāmprasād's work.[50] Rāmprasād comments in many of his other songs that Kāli is indifferent to his wellbeing, causes him to suffer, brings his worldly desires to nothing and his worldly goods to ruin. He also states that she does not behave like a mother should and that she ignores his pleas:

Can mercy be found in the heart of her who was born of the stone? [a reference to Kali as the daughter of Himalaya]

Were she not merciless, would she kick the breast of her lord?

Men call you merciful, but there is no trace of mercy in you, Mother.

You have cut off the heads of the children of others, and these you wear as a garland around your neck.

It matters not how much I call you "Mother, Mother." You hear me, but you will not listen.[1]

- ^ Kinsley (1997), p. 128.

To be a child of Kāli, Rāmprasād asserts, is to be denied of earthly delights and pleasures. Kāli is said to refrain from giving that which is expected. To the devotee, it is perhaps her very refusal to do so that enables her devotees to reflect on dimensions of themselves and of reality that go beyond the material world.[51]

A significant portion of Bengali devotional music features Kāli as its central theme and is known as Shyama Sangeet ("Music of the Night"). Mostly sung by male vocalists, today even women have taken to this form of music. One of the finest singers of Shyāma Sāngeet is Pannalal Bhattacharya.

Kāli is especially venerated in the festival of Kali Puja in eastern India—celebrated when the new moon day of Ashwin month coincides with the festival of Diwali. The practice of animal sacrifice is common during Kali Puja in Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, though it is rare outside of those areas. The Hindu temples where this takes place involves the ritual slaying of goats, chickens and sometimes male Water buffalos. Throughout India, the practice is becoming less common.[52] The rituals in eastern India temples where animals are killed are generally led by Brahmin priests.[53] A number of Tantric Puranas specify the ritual for how the animal should be killed. A Brahmin priest will recite a mantra in the ear of animal to be sacrificed, in order to free the animal from the cycle of life and death. Groups such as People for Animals continue to protest animal sacrifice based on court rulings forbidding the practice in some locations.[54]

In a unique form of Kāli worship, Shantipur worships Kāli in the form of a hand painted image of the deity known as Poteshwari (meaning the deity drawn on a piece of cloth).

Worship in the Western world

An academic study of western Kali enthusiasts noted that, "as shown in the histories of all cross-cultural religious transplants, Kali devotionalism in the West must take on its own indigenous forms if it is to adapt to its new environment."[55] Rachel Fell McDermott, Professor of Asian and Middle Eastern Cultures at Columbia University and author of several books on Kali, has noted the evolving views in the West regarding Kali and her worship. In 1998 she pointed out that:

A variety of writers and thinkers have found Kali an exciting figure for reflection and exploration, notably feminists and participants in New Age spirituality who are attracted to goddess worship. [For them], Kali is a symbol of wholeness and healing, associated especially with repressed female power and sexuality. [However, such interpretations often exhibit] confusion and misrepresentation, stemming from a lack of knowledge of Hindu history among these authors, [who only rarely] draw upon materials written by scholars of the Hindu religious tradition… It is hard to import the worship of a goddess from another culture: religious associations and connotations have to be learned, imagined or intuited when the deep symbolic meanings embedded in the native culture are not available.[55]

By 2003 McDermott amended her previous view by writing that:

...cross-cultural borrowing is appropriate and a natural by-product of religious globalization—although such borrowing ought to be done responsibly and self-consciously. If some Kali enthusiasts, therefore, careen ahead, reveling in a goddess of power and sex, many others, particularly since the early 1990s, have decided to reconsider their theological trajectories. These, whether of South Asian descent or not, are endeavoring to rein in what they perceive as excesses of feminist and New Age interpretations of the Goddess by choosing to be informed by, moved by, an Indian view of her character.[56]

Notes

- ↑ Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Literature." Journal of Indological Studies (Kyoto), Nos. 24 & 25 (2012–2013), 2014, pp. 80.

- ↑ Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Literature." Journal of Indological Studies (Kyoto), Nos. 24 & 25 (2012–2013), 2014, pp. 63-64.

- 1 2 Hawley (1982), p. 152.

- ↑ Harding (1993), p. xxv.

- ↑ McDaniel (2004), p. 5.

- ↑ McDaniel (2004), p. 104.

- ↑ McDermott (2003), p. 4.

- ↑ Pāṇini 4.1.42

- 1 2 3 Coburn (1984), pp. 111-112.

- ↑ McDermott (2001), p. 175

- ↑ Urban (2003).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kinsley (1997), p. 70.

- 1 2 Kinsley (1997), pp. 118-119.

- ↑ Jagadiswarananda (1953).

- ↑ Wangu (2003), p. 72.

- ↑ Kinsley (1997) p. 241 Footnotes.

- ↑ Rawson (1973).

- ↑ Sankaranarayanan (2001), p 127.

- ↑ White (2000), p. 466.

- ↑ Saradananda1(952), p. 624.

- ↑ Hati (1985), pp. 17–18.

- ↑ White (2000), p. 477.

- ↑ White (2000), p. 475.

- ↑ White (2000), pp. 463–488.

- ↑ McDaniel (2004), p.257.

- ↑ Harper (2012), p. 53.

- 1 2 3 4 Kinsley (1998), pp. 86-90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McDermott (2005), p. 53-55.

- ↑ McDermott (2005), p. 36-39.

- ↑ McDermott (2003) p. 54.

- ↑ Sircar (1998), pp. 74-78.

- ↑ Harding (1998), p. 217.

- 1 2 Harding (1993).

- ↑ https://unexplored.lonelyplanet.in/discovery/entry/929.html

- 1 2 Menon, Usha; Shweder, Richard A. (1994). "Kali's Tongue: Cultural Psychology and the Power of Shame in Orissa, India". In Kitayama, Shinobu; Markus, Hazel Rose. Emotion and Culture: Empirical Studies of Mutual Influence. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. pp. 241–284.

- 1 2 Krishna Dutta (3 June 2011). Calcutta: A Cultural and Literary History (Cities of the Imagination). Andrews UK Limited. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-904955-87-0.

- ↑ McDaniel (2004), p. 237.

- ↑ McDaniel (2004), p. 237.

- ↑ Harding (1993), p. xxiii.

- ↑ Nivedita (2001), p. 651.

- ↑ Kinsley (1977), p. 88.

- ↑ McDermott (2003), p. 53.

- ↑ Chawdhri (1992).

- 1 2 3 4 Kinsley (1997), pp. 122-124.

- ↑ Woodroffe (1922).

- ↑ Beck (1995), p. 145.

- ↑ Kinsley (1997), pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Kinsley (1997), p. 125.

- ↑ Kinsley (1997), p. 126.

- ↑ Kinsley (1997), pp. 125-126.

- ↑

- ↑ J. Fuller, C. (26 July 2004). The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India [Paperback] (Revised ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0-691-12048-X. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

Animal sacrifice is still practiced widely and is an important ritual in popular Hinduism

- ↑ Fuller (2004), p. 84, pp. 101–104.

- ↑ McDermott, Rachel Fell (2011). Revelry, rivalry, and longing for the goddesses of Bengal: the fortunes of Hindu festivals. New York, Chichester: Columbia University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-231-12918-3. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- 1 2 McDermott (1998), pp. 281-305.

- ↑ McDermott (2003), p. 285

References

- Beck, Guy L. (1995). Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1261-1.

- Chawdhri, L.R. (1992). Secrets of Yantra, Mantra and Tantra. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Coburn, Thomas (1984). Devī-Māhātmya – Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi. ISBN 81-208-0557-7.

- Feuerstein, Georg (1998). Tantra: The Path of Ecstasy. Shambhala.

- Harding, Elizabeth U. (1993). Kali: The Black Goddess of Dakshineswar. Nicolas Hays.

- Harper, Katherine Anne; Brown, Robert L. (2012). The Roots of Tantra. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-8890-4.

- Hati, Kamalpada; P.K., Pramanik (1985). Sri Ramakrishna: The Spiritual Glow. Orient Book Co.

- Hawley, John Stratton; Donna Marie, Wulff (1982). Sri Ramakrishna: The Spiritual Glow. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe.

- Jagadiswarananda, Swami (1953). Devi Mahatmyam. Ramakrishna Math.

- Kinsley, David R. (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press.

- Kinsley, David (1997). Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahavidyas. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Krishna, Gopi (1993). Living with Kundalini. Shambhala. ISBN 0-87773-947-1.

- McDermott, Rachel Fell (1998). "The Western Kali". In Hawley, John Stratton. Devi: Goddesses of India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- McDermott, Rachel Fell (2001). Singing to the Goddess: Poems to Kali and Uma from Bengal. Oxford University Press.

- McDermott, Rachel Fell (2003). Encountering Kali: In the Margins, at the Center, in the West. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- McDaniel, June (2004). Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal. Oxford University Press.

- Nivedita, Sister (2001). Rappaport, Helen, ed. Encyclopedia of Women Social Reformers. 1. ABC-CLIO.

- Rawson, Philip (1973). The Art of Tantra. Thames & Hudson.

- Sankaranarayanan, Sri (2001). Glory Of The Divine Mother: Devi Mahatmyam. Nesma Books India. ISBN 9788187936008.

- Saradananda, Swami (1952). 'Sri Ramakrishna: The Great Master. Ramakrishna Math.

- Sircar, Dineschandra (1998). The Śākta Pīṭhas. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0879-9.

- Snyder, William H. (2001). Time, Being, and Soul in the Oldest Sanskrit Sources. Global Academic Publishing. ISBN 9781586840723.

- Urban, Hugh (2001). "India's Darkest Heart: Kali in the Colonial Imagination". In McDermott, Rachel Fell. Encountering Kali: In the Margins, at the Center, in the West. Berkeley: University of California Press (published 2003).

- Wangu, Madhu Bazaz (2003). Images of Indian Goddesses. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-416-3.

- White, David Gordon (2000). Tantra in Practice. Princeton Press.

- Woodroffe, Sir John (1918). Shakti and Shâkta. Oxford Press/Ganesha & Co.

- Woodroffe, Sir John (1922). Karpuradi Stotra, Tantrik Texts Vol IX. Calcutta Agamanusandhana Samiti.

Further reading

- Bowker, John (2000). Oxford Concise Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford Press.

- Bunce, Frederick W. (1997). A Dictionary of Buddhist and Hindu Iconography (Illustrated). D.K. Print World.

- Craven, Roy C. (1997). Indian Art (revised). Thames & Hudson.

- Doniger, Wendy (2015). Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Kali. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Harshananda, Swami (1981). Hindu Gods & Goddesses. Ramakrishna Math.

- Mishra, T. N. (1997). Impact of Tantra on Religion and Art. D.K. Print World.

- Santideva, Sadhu (2000). Ascetic Mysticism. Cosmo Publications.

- Loriliai Biernacki, Renowned Goddess of Desire: Women, Sex, and Speech in Tantra Oxford Scholarship Online: September 2007, doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195327823.001.0001, ISBN 9780195327823

- Shanmukha Anantha Natha and Shri Ma Kristina Baird, Divine Initiation Shri Kali Publications (2001) ISBN 0-9582324-0-7 - Has a chapter on Mahadevi with a commentary on the Devi Mahatmyam from the Markandeya Purana.

- Ajit Mookerjee, Kali: The Feminine Force ISBN 0-89281-212-5

- Swami Satyananda Saraswati, Kali Puja ISBN 1-887472-64-9

- Ramprasad Sen, Grace and Mercy in Her Wild Hair: Selected Poems to the Mother Goddess ISBN 0-934252-94-7

- Sir John Woodroffe (a.k.a. Arthur Avalon) Hymns to the Goddess and Hymn to Kali ISBN 81-85988-16-1

- Robert E. Svoboda, Aghora, at the left hand of God ISBN 0-914732-21-8

- Dimitri Kitsikis, L'Orocc, dans l'âge de Kali ISBN 2-89040-359-9

- Lex Hixon, Mother of the Universe: Visions of the Goddess and Tantric Hymns of Enlightenment ISBN 0-8356-0702-X

- Neela Bhattacharya Saxena, In the Beginning is Desire: Tracing Kali's Footprints in Indian Literature ISBN 81-87981-61-X

- The Goddess Kali of Kolkata (ISBN 81-7476-514-X) by Shoma A. Chatterji

- Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (ISBN 0-500-51088-1) by Anna Dallapiccola

- In Praise of The Goddess: The Devimahatmyam and Its Meaning (ISBN 0-89254-080-X) by Devadatta Kali

- Seeking Mahadevi: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Great Goddess (ISBN 0-791-45008-2) Edited by Tracy Pintchman

- The Rise of the Goddess in the Hindu Tradition (ISBN 0-7914-2112-0) by Tracy Pintchman

- Narasimhananda, Swami, Prabuddha Bharata, January 2016, The Phalaharini Kali.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kali. |

- Kali at Encyclopædia Britannica