History of the United States Republican Party

Republican Party | |

|---|---|

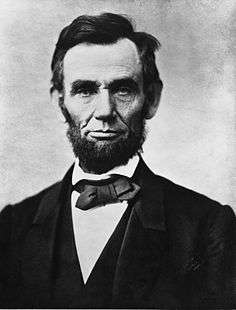

| Leader | Abraham Lincoln; Hannibal Hamlin |

| Founded | 1850s |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

The Republican Party, also commonly called the GOP (for "Grand Old Party"), is one of the world's oldest extant political parties. It is the second oldest existing political party in the United States after its primary rival, the Democratic Party. It emerged in 1854 to combat the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which threatened to extend slavery into the territories, and to promote more vigorous modernization of the economy. The Party had almost no presence in the South, but by 1858 in the North it had enlisted former Whigs and former Free Soil Democrats to form majorities in nearly every Northern state.

With its election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, and its success in guiding the Union to victory and abolishing slavery, the party came to dominate the national political scene until 1932. The Republican Party was based on northern white Protestants, businessmen, small business owners, professionals, factory workers, farmers, and African Americans. It was pro-business, supporting banks, the gold standard, railroads, and high tariffs to protect factory workers and grow industry faster. Under William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, it emphasized an expansive foreign policy.

The GOP lost its majorities during the Great Depression (1929–1940). Instead, the Democrats under Franklin D. Roosevelt formed a winning "New Deal" coalition, which was dominant from 1932 through 1964. That coalition collapsed in the mid-1960s, partly because of white Southern Democrats' disaffection with passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Republicans won five of the six presidential elections from 1968 to 1988, with Ronald Reagan as the party's iconic conservative hero. From 1992 to 2016, the Republican candidate has been elected to the White House in three of the seven presidential elections—and only in one out of those seven elections, in 2004, did he win the popular vote.

The GOP expanded its base throughout the South after 1968 (excepting 1976), largely due to its strength among socially conservative white Evangelical Protestants and traditionalist Roman Catholics. As white Democrats in the South lost dominance of the Democratic Party once U.S. courts declared the Democratic White Primary elections unconstitutional, the region began more taking on the two-party apparatus which characterized most of the nation. The Republican Party's transforming leader by 1980 was Reagan, whose conservative policies called for reduced government spending and regulation, lower taxes, and a strong anti-Soviet foreign policy. His influence upon the party persists, as nearly every GOP speaker still reveres him. Social scientists Theodore Caplow et al. argue, "The Republican party, nationally, moved from right-center toward the center in the 1940s and 1950s, then moved right again in the 1970s and 1980s."[1]

Ideological beginnings

The Republican party began as a coalition of anti-slavery "Conscience Whigs" and Free Soil Democrats opposed to the Kansas–Nebraska Act, submitted to Congress by Stephen Douglas in January 1854. The Act opened Kansas Territory and Nebraska Territory to slavery and future admission as slave states, thus implicitly repealing the prohibition on slavery in territory north of 36° 30′ latitude, which had been part of the Missouri Compromise. This change was viewed by Free Soil and Abolitionist Northerners as an aggressive, expansionist maneuver by the slave-owning South.

The Act was supported by all Southerners, by Northern "Doughface" (pro-Southern) Democrats and by other Northern Democrats persuaded by Douglas' doctrine of "popular sovereignty". In the North the old Whig Party was almost defunct. The opponents were intensely motivated and began forming a new party.[2]

The new party went well beyond the issue of slavery in the territories. It envisioned modernizing the United States—emphasizing giving free western land to farmers ("free soil") as opposed to letting slave owners buy up the best lands, expanded banking, more railroads, and factories. They vigorously argued that free market labor was superior to slavery and the very foundation of civic virtue and true republicanism—this was the "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men" ideology.[2]

The Republicans absorbed the previous traditions of its members, most of whom had been Whigs; others had been Democrats or members of third parties (especially the Free Soil Party and the American Party, also known as the Know Nothings). Many Democrats who joined were rewarded with governorships,[Note 1] or seats in the U.S. Senate,[Note 2] or House of Representatives.[Note 3] Since its inception, its chief opposition has been the Democratic Party, but the amount of flow back and forth of prominent politicians between the two parties was quite high from 1854 to 1896.

Historians have explored the ethnocultural foundations of the party, along the line that ethnic and religious groups set the moral standards for their members, who then carried those standards into politics. The churches also provided social networks that politicians used to sign up voters. The pietistic churches emphasized the duty of the Christian to purge sin from society. Sin took many forms—alcoholism, polygamy and slavery became special targets for the Republicans.[3]

The Yankees, who dominated New England, much of upstate New York, and much of the upper Midwest were the strongest supporters of the new party. This was especially true for the pietistic Congregationalists and Presbyterians among them and (during the war), the Methodists, along with Scandinavian Lutherans. The Quakers were a small tight-knit group that was heavily Republican. The liturgical churches (Roman Catholic, Episcopal, German Lutheran), by contrast, largely rejected the moralism of the Republican Party; most of their adherents voted Democratic.[3]

The early standard bearers of the Party expressed views of government that marked the first years of its existence. For instance, William H. Seward, New York governor who ran vied with Lincoln for the nomination in 1860, had called for welcoming immigrants with "all the sympathy that their misfortunes at home, their condition as strangers here, and their devotion to liberty, ought to excite."[4] And Lincoln, in his 1861 message to Congress, argued that the essential reason for preserving the central government was to maintain "in the world, that form, and substance of government, whose leading object is to elevate the condition of men – to lift artificial weights from all shoulders – to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all – to afford all, an unfettered start, and a fair chance, in the race of life."[5]

Organizational beginnings (1854)

The first "anti-Nebraska" local meeting where "Republican" was suggested as a name for a new anti-slavery party was held in a Ripon, Wisconsin schoolhouse on March 20, 1854.[6] The first statewide convention that formed a platform and nominated candidates under the name "Republican" was held near Jackson, Michigan on July 6, 1854. It declared their new party opposed to the expansion of slavery into new territories and selected a statewide slate of candidates. The Midwest took the lead in forming state party tickets, while the eastern states lagged a year or so.

There were no efforts to organize the party in the South, apart from St. Louis and a few areas adjacent to free states. The party initially had its base in the Northeast and Midwest.

Establishing a national party, and opposition

The party launched its first national convention in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on February 22, 1856,[7] with its first national nominating convention held in the summer in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,[8] presided by Francis Preston Blair, Sr..

John C. Frémont ran as the first Republican nominee for President in 1856 behind the slogan: "Free soil, free silver, free men, Frémont and victory!" Although Frémont's bid was unsuccessful, the party showed a strong base. It dominated in New England, New York and the northern Midwest, and had a strong presence in the rest of the North. It had almost no support in the South, where it was roundly denounced in 1856–1860 as a divisive force that threatened civil war.[9]

Without using the term "containment", the new Party in the mid-1850s proposed a system of containing slavery, once it gained control of the national government. Historian James Oakes explains the strategy:

The federal government would surround the south with free states, free territories, and free waters, building what they called a 'cordon of freedom' around slavery, hemming it in until the system's own internal weaknesses forced the slave states one by one to abandon slavery.[10]

Leading up to the second presidential election after the party's establishment, disdain for it grew considerably among Democrats, particularly those from the South. In reference to the Republicans' anti-slavery position, prominent Democrats applied the slur "Black Republican" against them, as seen repeatedly in the speeches of Senator Stephen Douglas during the Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858 in Illinois. During the presidential campaign in 1860, at a time of escalating tension between the North and South, Abraham Lincoln addressed the harsh treatment of Republicans in the South in his famous Cooper Union speech:

[W]hen you speak of us Republicans, you do so only to denounce us as reptiles, or, at the best, as no better than outlaws. You will grant a hearing to pirates or murderers, but nothing like it to "Black Republicans." ....But you will not abide the election of a Republican president! In that supposed event, you say, you will destroy the Union; and then, you say, the great crime of having destroyed it will be upon us! That is cool. A highwayman holds a pistol to my ear, and mutters through his teeth, "Stand and deliver, or I shall kill you, and then you will be a murderer!"

The Civil War and Republican dominance: 1860–1896

The election of Lincoln in 1860 opened a new era of Republican dominance based in the industrial North and agricultural Midwest.

The Third Party System was dominated by the Republican Party (it lost the presidency only in 1884 and 1892). Lincoln proved brilliantly successful in uniting the factions of his party to fight for the Union.[11] However he usually fought the Radical Republicans who demanded harsher measures. Most Democrats at first were War Democrats, and supportive until the Fall of 1862. When Lincoln added the abolition of slavery as a war goal, many war Democrats became "peace Democrats".

Most of the state Republican parties accepted the antislavery goal except Kentucky. In Congress, the party passed major legislation to promote rapid modernization, including a national banking system, high tariffs, the first temporary income tax, many excise taxes, paper money issued without backing ("greenbacks"), a huge national debt, homestead laws, railroads, and aid to education and agriculture.

The Republicans denounced the peace-oriented Democrats as disloyal Copperheads and won enough War Democrats to maintain their majority in 1862; in 1864, they formed a coalition with many War Democrats as the National Union Party which reelected Lincoln easily. During the war, upper middle-class men in major cities formed Union Leagues, to promote and help finance the war effort.

Reconstruction: Freedmen, "carpetbaggers", and "scalawags"

In Reconstruction, how to deal with the ex-Confederates and the freed slaves, or freedmen, were the major issues. By 1864, Radical Republicans controlled Congress and demanded more aggressive action against slavery, and more vengeance toward the Confederates. Lincoln held them off, but just barely. Republicans at first welcomed President Andrew Johnson; the Radicals thought he was one of them and would take a hard line in punishing the South.

Johnson however broke with them and formed a loose alliance with moderate Republicans and Democrats. The showdown came in the Congressional elections of 1866, in which the Radicals won a sweeping victory and took full control of Reconstruction, passing key laws over the veto. Johnson was impeached by the House, but acquitted by the Senate.

With the election of Ulysses S. Grant in 1868, the Radicals had control of Congress, the party and the Army, and attempted to build a solid Republican base in the South using the votes of Freedmen, Scalawags and Carpetbaggers,[9] supported directly by U.S. Army detachments. Republicans all across the South formed local clubs called Union Leagues that effectively mobilized the voters, discussed issues, and when necessary fought off Ku Klux Klan (KKK) attacks. Thousands died on both sides.[12]

Grant supported radical reconstruction programs in the South, the Fourteenth Amendment, and equal civil and voting rights for the freedmen. Most of all he was the hero of the war veterans, who marched to his tune. The party had become so large that factionalism was inevitable; it was hastened by Grant's tolerance of high levels of corruption typified by the Whiskey Ring.

Many of the founders of the GOP joined the Liberal movement, as did many powerful newspaper editors. They nominated Horace Greeley for president, who also gained the Democratic nomination, but the ticket was defeated in a landslide. The depression of 1873 energized the Democrats. They won control of the House and formed "Redeemer" coalitions which recaptured control of each southern state, in some cases using threats and violence.

Reconstruction came to an end when the contested election of 1876 was awarded by a special electoral commission to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes who promised, through the unofficial Compromise of 1877, to withdraw federal troops from control of the last three southern states. The region then became the Solid South, giving overwhelming majorities of its electoral votes and Congressional seats to the Democrats through 1964.

In terms of racial issues, Sarah Woolfolk Wiggins argues that in Alabama:

- White Republicans as well as Democrats solicited black votes but reluctantly rewarded blacks with nominations for office only when necessary, even then reserving the more choice positions for whites. The results were predictable: these half-a-loaf gestures satisfied neither black nor white Republicans. The fatal weakness of the Republican Party in Alabama, as elsewhere in the South, was its inability to create a biracial political party. And while in power even briefly, they failed to protect their members from Democratic terror. Alabama Republicans were forever on the defensive, verbally and physically.[13]

Social pressure eventually forced most Scalawags to join the conservative/Democratic Redeemer coalition. A minority persisted and formed the "tan" half of the "Black and Tan" Republican Party, a minority in every southern state after 1877.[14]

In several southern states, the "Lily Whites", who sought to recruit white Democrats to the Republican Party, attempted to purge the Black and Tan faction or at least to reduce its influence. Among such "Lily White" leaders in the early 20th century, Arkansas' Wallace Townsend was the party's gubernatorial nominee in 1916 and 1920, and its veteran national GOP committeeman.[15]

Starting in the 1870s Southern Republicans were divided into two factions: the lily-white faction, which was practically all-white, and the biracial black-and-tan faction.[16] The factionalism flared up in 1928[17] and 1952.[18] The final victory of its opponent the lily-white faction came in 1964.[19]

The Gilded Age: 1877–1890

The "GOP" (short for Grand Old Party, as it was now nicknamed) split into factions in the late 1870s. The Stalwarts, followers of Senator Roscoe Conkling, defended the spoils system. The Half-Breeds, who followed Senator James G. Blaine of Maine, pushed for reform of the Civil service. Independents who opposed the spoils system altogether were called "Mugwumps". In 1884 Mugwumps rejected James G. Blaine as corrupt and helped elect Democrat Grover Cleveland; most returned to the party by 1888.

As the Northern post-war economy boomed with industry, railroads, mines, and fast-growing cities, as well as prosperous agriculture, the Republicans took credit and promoted policies to keep the fast growth going. The Democratic Party was largely controlled by pro-business Bourbon Democrats until 1896. The GOP supported big business generally, the gold standard, high tariffs, and generous pensions for Union veterans. By 1890, however, the Republicans had agreed to the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and the Interstate Commerce Commission in response to complaints from owners of small businesses and farmers. The high McKinley Tariff of 1890 hurt the party and the Democrats swept to a landslide in the off-year elections, even defeating McKinley himself.

Foreign affairs seldom became partisan issues (except for the annexation of Hawaii, which Republicans favored and Democrats opposed). Much more salient were cultural issues. The GOP supported the pietistic Protestants (especially the Methodists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and Scandinavian Lutherans) who demanded Prohibition. That angered wet Republicans, especially German Americans, who broke ranks in 1890–1892, handing power to the Democrats.[20]

Demographic trends aided the Democrats, as the German and Irish Catholic immigrants were mostly Democrats, and outnumbered the British and Scandinavian Republicans. During the 1880s, elections were remarkably close. The Democrats usually lost, but won in 1884 and 1892. In the 1894 Congressional elections, the GOP scored the biggest landslide in its history, as Democrats were blamed for the severe economic depression 1893–1897 and the violent coal and railroad strikes of 1894.[20]

Ethnocultural politics: pietistic Republicans versus liturgical Democrats

| Voting Behavior by Religion, Northern U.S. Late 19th century[21] | ||

| % Dem | % GOP | |

|---|---|---|

| Immigrant Groups | ||

| Irish Catholics | 80 | 20 |

| All Catholics | 70 | 30 |

| Confessional German Lutherans | 65 | 35 |

| German Reformed | 60 | 40 |

| French Canadian Catholics | 50 | 50 |

| Less Confessional German Lutherans | 45 | 55 |

| English Canadians | 40 | 60 |

| British Stock | 35 | 65 |

| German Sectarians | 30 | 70 |

| Norwegian Lutherans | 20 | 80 |

| Swedish Lutherans | 15 | 85 |

| Haugean Norwegians | 5 | 95 |

| Natives: Northern Stock | ||

| Quakers | 5 | 95 |

| Free Will Baptists | 20 | 80 |

| Congregational | 25 | 75 |

| Methodists | 25 | 75 |

| Regular Baptists | 35 | 65 |

| Blacks | 40 | 60 |

| Presbyterians | 40 | 60 |

| Episcopalians | 45 | 55 |

| Natives: Southern Stock (living in North) | ||

| Disciples | 50 | 50 |

| Presbyterians | 70 | 30 |

| Baptists | 75 | 25 |

| Methodists | 90 | 10 |

From 1860 to 1912, the Republicans took advantage of the association of the Democrats with "Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion". Rum stood for the liquor interests and the tavernkeepers, in contrast to the GOP, which had a strong dry element. "Romanism" meant Roman Catholics, especially Irish Americans, who ran the Democratic Party in every big city, and whom the Republicans denounced for political corruption. "Rebellion" stood for the Democrats of the Confederacy, who tried to break the Union in 1861, and the Democrats in the North, called "Copperheads", who sympathized with them.

Demographic trends aided the Democrats, as the German and Irish Catholic immigrants were Democrats, and outnumbered the English and Scandinavian Republicans. During the 1880s and 1890s, the Republicans struggled against the Democrats' efforts, winning several close elections and losing two to Grover Cleveland (in 1884 and 1892).

Religious lines were sharply drawn.[22] Methodists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Scandinavian Lutherans, and other pietists in the North were tightly linked to the GOP. In sharp contrast, liturgical groups, especially the Catholics, Episcopalians, and German Lutherans, looked to the Democratic Party for protection from pietistic moralism, especially prohibition. Both parties cut across the class structure, with the Democrats more bottom-heavy.

Cultural issues, especially prohibition and foreign language schools became important because of the sharp religious divisions in the electorate. In the North, about 50% of the voters were pietistic Protestants (Methodists, Scandinavian Lutherans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Disciples of Christ) who believed the government should be used to reduce social sins, such as drinking.[22]

Liturgical churches (Roman Catholics, German Lutherans, Episcopalians) comprised over a quarter of the vote and wanted the government to stay out of the morality business. Prohibition debates and referendums heated up politics in most states over a period of decade, as national prohibition was finally passed in 1919 (and repealed in 1933), serving as a major issue between the wet Democrats and the dry GOP.[22]

The Progressive Era: 1896–1932

The election of William McKinley in 1896 is widely seen as a resurgence of Republican dominance and is cited as a realigning election.[23]

The Progressive Era (or "Fourth Party System") was dominated by Republican presidents, with the sole exception of Democrat Woodrow Wilson, 1913–1921. McKinley promised that high tariffs would end the severe hardship caused by the Panic of 1893, and that the GOP would guarantee a sort of pluralism in which all groups would benefit. He denounced William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee, as a dangerous radical whose plans for "Free Silver" at 16–1 (or Bimetallism) would bankrupt the economy.

McKinley relied heavily on finance, railroads, industry and the middle classes for his support and cemented the Republicans as the party of business; his campaign manager, Ohio's Mark Hanna, developed a detailed plan for getting contributions from the business world, and McKinley outspent his rival William Jennings Bryan by a large margin. This emphasis on business was in part mitigated by Theodore Roosevelt, the presidential successor after McKinley's assassination in 1901, who engaged in trust-busting. McKinley was the first president to promote pluralism, arguing that prosperity would be shared by all ethnic and religious groups.[20]

Theodore Roosevelt, who became president in 1901, had the most dynamic personality of the era. Roosevelt had to contend with men like Senator Mark Hanna, whom he outmaneuvered to gain control of the convention in 1904 that renominated him and he won after promising to continue McKinley's policies. More difficult to handle was conservative House Speaker Joseph Gurney Cannon.

Roosevelt achieved modest legislative gains in terms of railroad legislation and pure food laws. He was more successful in Court, bringing antitrust suits that broke up the Northern Securities Company trust and Standard Oil. Roosevelt moved left in his last two years in office but was unable to pass major Square Deal proposals. He did succeed in naming his successor Secretary of War William Howard Taft who easily defeated Bryan again in the 1908 presidential election.

The tariff issue was pulling the GOP apart. Roosevelt tried to postpone the issue but Taft had to meet it head on in 1909 with the Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act. Eastern conservatives led by Nelson W. Aldrich wanted high tariffs on manufactured goods (especially woolens), while Midwesterners called for low tariffs. Aldrich tricked them by lowering the tariff on farm products, which outraged the farmers. Insurgent Midwesterners led by George Norris revolted against the conservatives led by Speaker Cannon. The Democrats won control of the House in 1910, as the rift between insurgents and conservatives widened.[9]

In 1912 Roosevelt broke with Taft and tried for a third term. He was outmaneuvered by Taft and lost the nomination. Roosevelt led his delegates out of the convention and created a new party, the Progressive, or "Bull Moose" ticket in the election of 1912. Few party leaders followed him except Hiram Johnson of California. Roosevelt had the support of many notable women reformers, including Jane Addams.[24] The Roosevelt-caused split in the Republican vote resulted in a decisive victory for Democrat Woodrow Wilson, temporarily interrupting the Republican era.[9]

The Republicans welcomed the Progressive Era at the state and local level. The first important reform mayor was Hazen S. Pingree of Detroit (1890–1897) who was elected governor of Michigan in 1896. In New York City the Republicans joined nonpartisan reformers to battle Tammany Hall, and elected Seth Low (1902–1903). Golden Rule Jones was first elected mayor of Toledo as a Republican in 1897, but was reelected as an independent when his party refused to renominate him. Many Republican civic leaders, following the example of Mark Hanna, were active in the National Civic Federation, which promoted urban reforms and sought to avoid wasteful strikes.

The party controlled the presidency throughout the 1920s, running on a platform of opposition to the League of Nations, high tariffs, and promotion of business interests. Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover were resoundingly elected in 1920, 1924, and 1928 respectively. The breakaway efforts of Senator Robert LaFollette in 1924 failed to stop a landslide for Coolidge, and his movement fell apart. The Teapot Dome Scandal threatened to hurt the party but Harding died and Coolidge blamed everything on him, as the opposition splintered in 1924.[20]

The pro-business policies of the decade seemed to produce an unprecedented prosperity—until the Wall Street Crash of 1929 heralded the Great Depression. Although the party did very well in large cities and among ethnic Catholics in presidential elections of 1920–1924, it was unable to hold those gains in 1928.[20] By 1932 the cities—for the first time ever—had become Democratic strongholds.

Hoover, by nature an activist, attempted to do what he could to alleviate the widespread suffering caused by the Depression, but his strict adherence to what he believed were Republican principles precluded him from establishing relief directly from the federal government. The Depression cost Hoover the presidency with the 1932 landslide election of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt's New Deal coalition controlled American politics for most of the next three decades, excepting the two-term presidency of Republican Dwight Eisenhower. The Democrats made major gains in the 1930 midterm elections, giving them congressional parity (though not control) for the first time since Woodrow Wilson's presidency.[9]

Progressives and Liberals

The Republican Party had a progressive element, typified in the early 20th century by Theodore Roosevelt in the 1907–1912 period (Roosevelt was more conservative at other points), Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr. and his sons in Wisconsin (from about 1900 to 1946), and western leaders such as Senator Hiram Johnson in California, Senator George W. Norris in Nebraska, Senator Bronson M. Cutting in New Mexico, Congresswoman Jeannette Rankin in Montana, and Senator William Borah in Idaho. They were generally progressive in domestic policy, supported unions,[25] and supported much of the New Deal, but were isolationist in foreign policy.[26] This element died out by the 1940s. Outside Congress, of the leaders who supported Theodore Roosevelt in 1912, most opposed the New Deal.[27]

Starting in the 1930s a number of Northeastern Republicans took liberal positions regarding labor unions, spending and New Deal policies. They included Mayor Fiorello La Guardia in New York City, Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York,[28] Governor Earl Warren of California, Senator Clifford P. Case of New Jersey, Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. of Massachusetts, Senator Prescott Bush of Connecticut (father and grandfather of the two Bush presidents), Senator Jacob K. Javits of New York, Governor William Scranton of Pennsylvania, and Governor George W. Romney of Michigan.[29] The most notable of them all was Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller of New York.[30] They generally advocated a free-market, but with some level of regulation. Rockefeller required employable welfare recipients to take available jobs or job training.[31]

While the media sometimes called them "Rockefeller Republicans", the liberal Republicans never formed an organized movement or caucus, and lacked a recognized leader. They promoted economic growth and high state and federal spending, while accepting high taxes and much liberal legislation, with the proviso they could administer it more efficiently. They opposed the Democratic big city machines while welcoming support from labor unions and big business alike. Religion and social issues were not high on their agenda. In foreign policy they were internationalists, throwing their support to Dwight D. Eisenhower over the conservative leader Robert A. Taft in 1952. They were often called the "Eastern Establishment" by conservatives such as Barry Goldwater.[32]

The Goldwater conservatives fought this establishment from 1960,[33] defeated it in 1964, and eventually retired most of its members, although some became Democrats like Senator Charles Goodell and Mayor John Lindsay in New York.[34] President Richard Nixon adopted many of their positions, especially regarding health care, welfare spending, environmentalism and support for the arts and humanities.[35] After Congressman John B. Anderson of Illinois bolted the party in 1980 and ran as an independent against Reagan, the liberal GOP element faded away. Their old strongholds in the Northeast are now mostly held by Democrats.[32][36]

Political firsts for women and minorities

From its inception in 1854 to 1964, when Senate Republicans pushed hard for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 against a filibuster by Senate Democrats, the GOP had a reputation for supporting blacks and minorities. In 1869, the Republican-controlled legislature in Wyoming Territory and its Republican governor John Allen Campbell made it the first jurisdiction to grant voting rights to women. In 1875, California swore in the first Hispanic governor, Republican Romualdo Pacheco. In 1916 Jeannette Rankin of Montana became the first woman in Congress—and indeed the first woman in any high level government position. In 1928, New Mexico elected the first Hispanic U.S. Senator, Republican Octaviano Larrazolo. In 1898, the first Jewish U.S. Senator elected from outside of the former Confederacy was Republican Joseph Simon of Oregon. In 1924, the first Jewish woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives was Republican Florence Kahn of California. In 1928, the Republican U.S. Senate Majority Leader, Charles Curtis of Kansas, who grew up on the Kaw Indian reservation, became the first person of significant non-European ancestry to be elected to national office, as Vice President of the United States for Herbert Hoover.

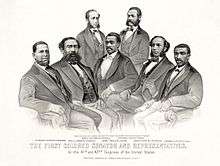

Blacks generally identified with the GOP until the 1930s. Every African American who served in the U.S. House of Representatives before 1935, and all of the African Americans who served in the U.S. Senate before 1979, were Republicans. Frederick Douglass after the Civil War and Booker T. Washington in the early 20th century were prominent Republican spokesmen.

Fighting the New Deal Coalition: 1932–1980

Historian George H. Nash argues:

Unlike the "moderate," internationalist, largely eastern bloc of Republicans who accepted (or at least acquiesced in) some of the "Roosevelt Revolution" and the essential premises of President Truman's foreign policy, the Republican Right at heart was counterrevolutionary. Anticollectivist, anti-Communist, anti-New Deal, passionately committed to limited government, free market economics, and congressional (as opposed to executive) prerogatives, the G.O.P. conservatives were obliged from the start to wage a constant two-front war: against liberal Democrats from without and "me-too" Republicans from within.[37]

The Old Right emerged in opposition to the New Deal of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Hoff says, "moderate Republicans and leftover Republican Progressives like Hoover composed the bulk of the Old Right by 1940, with a sprinkling of former members of the Farmer-Labor party, Non-Partisan League, and even a few midwestern prairie Socialists."[38]

1933–1938

After Roosevelt took office in 1933, New Deal legislation sailed through Congress at lightning speed. In the 1934 midterm elections, ten Republican senators went down to defeat, leaving them with only 25 against 71 Democrats. The House of Representatives was also split in a similar ratio. The "Second New Deal" was heavily criticized by the Republicans in Congress, who likened it to class warfare and socialism. The volume of legislation, as well as the inability of the Republicans to block it, soon made the opposition to Roosevelt develop into bitterness and sometimes hatred for "that man in the White House." Former President Hoover became a leading orator crusading against the New Deal, hoping unrealistically to be nominated again for president.[39][40]

Most major newspaper publishers favored Republican moderate Alf Landon for president. In the nation's 15 largest cities the newspapers that editorially endorsed Landon represented 70% of the circulation, while Roosevelt won 69% of the actual voters in those cities. Ignoring the press, FDR used the radio to reach voters directly.[41]

FDR carried 46 of the 48 states thanks to traditional Democrats along with newly energized labor unions, city machines, and the WPA. The realignment creating the Fifth Party System was firmly in place.[42] Since 1928 the GOP had lost 178 House seats, 40 Senate seats, and 19 governorships; it retained a mere 89 seats in the House and 16 in the Senate.[43]

The black vote held for Hoover in 1932, but started moving toward Roosevelt. By 1940 the majority of northern blacks were voting Democratic. Roosevelt made sure blacks had a share in relief programs, the wartime Army, and wartime defense industry, but did not challenge segregation or the denial of voting rights in the South.[44]

Minority parties tend to factionalize and after 1936 the GOP split into a conservative faction (dominant in the West and Midwest) and a liberal faction (dominant in the Northeast)—combined with a residual base of inherited progressive Republicanism active throughout the century. In 1936 Kansas governor Alf Landon and his young followers defeated the Herbert Hoover faction. Landon generally supported most New Deal programs, but carried only two states in the Roosevelt landslide with his moderate campaign. The GOP was left with only 16 senators and 88 representatives to oppose the New Deal, with Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. as the sole victor over a Democratic incumbent.

Roosevelt alienated many conservative Democrats, in 1937, by his unexpected plan to "pack" the Supreme Court via the Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937. Following a sharp recession that hit early in 1938, major strikes all over the country, the CIO and AFL competing with each other for membership, and Roosevelt's failed efforts to radically reorganize the Supreme Court, the Democrats were in disarray. Meanwhile, the GOP was united; they had shed their weakest members in a series of defeats since 1930.[45] Re-energized Republicans focused attention on strong fresh candidates in major states, especially Robert A. Taft the conservative from Ohio,[46] Earl Warren the moderate who won both the Republicans and the Democratic primaries in California,[47] and Thomas Dewey the crusading prosecutor from New York.[48] The GOP comeback in 1938 was made possible by carrying 50% of the vote outside the South, giving GOP leaders confidence it had a strong base for the 1940 presidential election.[49][50]

The GOP gained 75 House seats in 1938, but were still a minority. Conservative Democrats, mostly from the South, joined with Republicans led by Senator Robert A. Taft to create the conservative coalition, which dominated domestic issues in Congress until 1964.[51]

1939–1952

From 1939 through 1941, there was a sharp debate within the GOP about support for Britain in World War II. Internationalists, such as Henry Stimson and Frank Knox, wanted to support Britain and isolationists, such as Robert A. Taft and Arthur Vandenberg, strongly opposed these moves as unwise, if not unconstitutional. The America First movement was a bipartisan coalition of isolationists. In 1940, a total unknown, Wendell Willkie, at the last minute, won over the party, the delegates and was nominated. He crusaded against the inefficiencies of the New Deal and Roosevelt's break with the strong tradition against a third term.[28]

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 ended the isolationist-internationalist debate. The Republicans further cut the Democratic majority in the 1942 midterm elections. With wartime production creating prosperity, the Conservative coalition terminated most New Deal relief programs.[28]

Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio represented the wing of the party that continued to oppose New Deal reforms and continued to champion non-interventionism. Thomas Dewey, governor of New York, represented the Northeastern wing of the party. Dewey did not reject the New Deal programs, but demanded more efficiency, more support for economic growth, and less corruption. He was more willing than Taft to support Britain in 1939–1940. After the war the isolationists wing strenuously opposed the United Nations, and was half-hearted in opposition to world Communism.[28][52]

As a minority party, the GOP had two wings: The "left wing" supported most of the New Deal while promising to run it more efficiently. The "right wing" opposed the New Deal from the beginning and managed to repeal large parts during the 1940s in cooperation with conservative southern Democrats in the conservative coalition. Liberals, led by Dewey, dominated the Northeast. Conservatives, led by Taft, dominated the Midwest.[53]

The West was split, and the South was still solidly Democratic. Dewey did not reject the New Deal programs, but demanded more efficiency, more support for economic growth, and less corruption. He was more willing than Taft to support Britain in the early years of the war. In 1944, a clearly frail Roosevelt defeated Dewey, who was now governor of New York, for his fourth term, but Dewey made a good showing that would lead to his selection as the candidate in 1948.[53]

Roosevelt died in April 1945, and Harry S. Truman, a less liberal Democrat became president and replaced most of FDR's top appointees. With the end of the war, unrest among organized labor led to many strikes in 1946, and the resulting disruptions helped the GOP. With the blunders of the Truman administration in 1945 and 1946, the slogans "Had Enough?" and "To Err is Truman" became Republican rallying cries, and the GOP won control of Congress for the first time since 1928, with Joseph William Martin, Jr. as Speaker of the House. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 was designed to balance the rights of management and labor. It was the central issue of many elections in industrial states in the 1940s to 1950s, but the unions were never able to repeal it.

In 1948, with Republicans split left and right, Truman boldly called Congress into a special session, and sent it a load of liberal legislation consistent with the Dewey platform, and dared them to act on it, knowing that the conservative Republicans would block action. Truman then attacked the Republican "Do-Nothing Congress" as a whipping boy for all of the nation's problems. Truman stunned Dewey and the Republicans in the election with a plurality of just over two million popular votes (out of nearly 49 million cast), but a decisive 303–189 victory in the Electoral College.

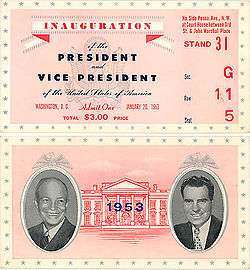

Eisenhower and Nixon: 1952–1974

In 1952, Dwight D. Eisenhower, an internationalist allied with the Dewey wing, was drafted as a GOP candidate by a small group of Republicans led by Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., in order that he challenge Taft on foreign policy issues. The two men were not far apart on domestic issues. Eisenhower's victory broke a twenty-year Democratic lock on the White House. Eisenhower did not try to roll back the New Deal, but he did expand the Social Security system and built the Interstate Highway System.

After 1945 the isolationists in the conservative wing opposed the United Nations, and were half-hearted in opposition to the expansion of communism around the world.[54] A garrison state to fight Communism, they believed, would mean regimentation and government controls at home. Eisenhower, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force Commander, defeated Taft in 1952 on foreign policy issues.

Citizens for Eisenhower

To circumvent the local Republican Party apparatus mostly controlled by Taft supporters, the Eisenhower forces created a nationwide network of grass-roots clubs, "Citizens for Eisenhower". Independents and Democrats were welcome, as the group specialized in canvassing neighborhoods and holding small group meetings. Citizens for Eisenhower hoped to revitalize the GOP by expanding its activist ranks and by supporting moderate and internationalist policies. It did not endorse candidates other than Eisenhower. However, Eisenhower paid it little attention after he won, and it failed to maintain its impressive starting momentum. Instead the conservative Republicans became energized, leading to the Barry Goldwater nomination of 1964. Long-time Republican activists viewed the newcomers with suspicion and hostility. More significantly, activism in support of Eisenhower did not translate into enthusiasm for the party cause.[55]

Once in office, however, Eisenhower was not an effective party leader and Nixon increasingly took that role. Historian David Reinhard concludes that Eisenhower lacked sustained political commitment, refused to intervene in state politics, failed to understand the political uses of presidential patronage, and overestimated his personal powers of persuasion and conciliation. Eisenhower's attempt in 1956 to convert the GOP to "Modern Republicanism" was his "grandest flop." It was a vague proposal with weak staffing and little financing or publicity that caused turmoil inside the local parties across the country. The GOP carried both houses of Congress in 1952 on Ike's coattails, but in 1954 lost both and would not regain the Senate until 1980 nor the House until 1994. The problem, says Reinhard, was the "voters liked Ike—but not the GOP."[56]

Nixon and Goldwater

Eisenhower was an exception to most presidents in that he usually let Vice President Richard Nixon handle party affairs (controlling the national committee and taking the roles of chief spokesman and chief fundraiser). Nixon was defeated in 1960 in a close election, weakening his moderate wing of the party.[57]

The conservatives in 1964 made a comeback under the leadership of Barry Goldwater who defeated moderates and liberals such as Nelson Rockefeller and Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., as the Republican candidate for the 1964 election. Goldwater was strongly opposed to the New Deal and the United Nations, but he rejected isolationism and containment, calling for an aggressive anti-Communist foreign policy.[58]

In the presidential election of 1964, he was defeated by Lyndon Johnson in a landslide that brought down many senior Republican Congressmen across the country. Goldwater won five states in the deep South, the strongest showing by a Republican presidential candidate in the South since 1872. Goldwater blamed the magnitude of his defeat on the assassination of John F. Kennedy a year before the election, and on Johnson running a successful campaign.

The New Deal Coalition collapsed in the mid-1960s in the face of urban riots, the Vietnam War, the opposition of many Southern Democrats to desegregation and the Civil Rights Movement and disillusionment that the New Deal could be revived by Lyndon Johnson's Great Society. Nixon defeated both Hubert Humphrey and George C. Wallace in 1968. When the Democratic left took over their party in 1972, Nixon won reelection by carrying 49 states.

Nixon's involvement in Watergate brought disgrace and a forced resignation in 1974 and any long-term movement toward the GOP was interrupted by the scandal. Gerald Ford succeeded Nixon and gave him a full pardon—thereby giving the Democrats a powerful issue they used to sweep the 1974 off-year elections. Ford never fully recovered, and in 1976 he barely defeated Ronald Reagan for the nomination. The Democrats made major gains in Congress, and the taint of Watergate and the nation's economic difficulties contributed to the election of Democrat Jimmy Carter in 1976, running as a Washington outsider.

Ronald Reagan was elected President in the 1980 election by a landslide vote, not predicted by most voter polling. Running on a "Peace Through Strength" platform to combat the Communist threat and massive tax cuts to revitalize the economy, Reagan's strong persona proved too much for Carter. Reagan's election also gave Republicans control of the Senate for the first time in decades.

Dubbed the "Reagan Revolution" he fundamentally altered several long standing debates in Washington, namely dealing with the Soviet threat and reviving the economy. His election saw the conservative wing of the party gain control. While reviled by liberal opponents in his day, his proponents contend his programs provided unprecedented economic growth, and spurred the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Detractors of Reagan's policies note that although Reagan promised to simultaneously slash taxes, massively increase defense spending and balance the budget, by the time he left office the nation's budget deficit had tripled in his eight years in office. In 2009 Reagan's budget director noted that the "debt explosion has resulted not from big spending by the Democrats, but instead the Republican Party's embrace, about three decades ago, of the insidious doctrine that deficits don't matter if they result from tax cuts". He inspired conservatives to greater electoral victories by being reelected in a landslide against Walter Mondale in 1984 but oversaw the loss of the Senate in 1986.

| Strength of parties in 1977[59] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Republican | Democratic | Independent |

| Party ID (Gallup) | 22% | 47% | 31% |

| Congressmen | 181 | 354 | |

| House | 143 | 292 | |

| Senate | 38 | 62 | |

| % House popular vote nationally | 42% | 56% | 2% |

| in the East | 41% | 57% | 2% |

| in the South | 37% | 62% | 2% |

| in the Midwest | 47% | 52% | 1% |

| in the West | 43% | 55% | 2% |

| Governors | 12 | 37 | 1[Note 4] |

| State Legislators | 2,370 | 5,128 | 55 |

| 31% | 68% | 1% | |

| State legislature control | 18 | 80 | 1[Note 4] |

| in the East | 5 | 13 | 0 |

| in the South | 0 | 32 | 0 |

| in the Midwest | 5 | 17 | 1 |

| in the West | 8 | 18 | 0 |

| States' one party control of legislature and governorship |

1 | 29 | 0 |

Moderate Republicans of 1960–1980

The term Rockefeller Republican was used 1960–1980 to designate a faction of the party holding "moderate" views similar to those of Nelson Rockefeller, governor of New York from 1959 to 1974 and vice president under President Gerald Ford in 1974–1977. Before Rockefeller, Tom Dewey, governor of New York 1942–1954 and GOP presidential nominee in 1944 and 1948 was the leader. Dwight Eisenhower and his aide Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., reflected many of their views.

An important moderate leader in the 1950s was Connecticut Republican Senator Prescott Bush, father and grandfather, respectively, of presidents George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush. After Rockefeller left the national stage in 1976, this faction of the party was more often called "moderate Republicans", in contrast to the conservatives who rallied to Ronald Reagan.

Historically, Rockefeller Republicans were moderate or liberal on domestic and social policies. They favored New Deal programs, including regulation and welfare. They were very strong supporters of civil rights. They were strongly supported by big business on Wall Street (New York City). In fiscal policy they favored balanced budgets and relatively high tax levels to keep the budget balanced. They sought long-term economic growth through entrepreneurship, not tax cuts.

In state politics, they were strong supporters of state colleges and universities, low tuition, and large research budgets. They favored infrastructure improvements, such as highway projects. In foreign policy they were internationalists, and anti-Communists. They felt the best way to counter Communism was sponsoring economic growth (through foreign aid), maintaining a strong military, and keeping close ties to NATO. Geographically their base was the Northeast, from Maine to Pennsylvania, where they had the support of major corporations and banks, and worked well with labor unions.

The moderate Republicans were top-heavy, with a surplus of high visibility national leaders and a shortage of grass roots workers. Most of all they lack the numbers, the enthusiasm and excitement the conservatives could mobilize—the moderates decided it must be an un-American level of fanaticism that drove their opponents. Doug Bailey, a senior Rockefeller aide recalled, "there was a mentality in [Rockefeller's] campaign staff that, 'Look, we have got all this money. We should be able to buy the people necessary to get this done. And you buy from the top down.'" Bailey discovered that the Rockefeller team never understood that effective political organizations are empowered from the bottom up, not the top down.[60]

Barry Goldwater crusaded against the Rockefeller Republicans, beating Rockefeller narrowly in the California primary of 1964 giving the Arizona senator, all of the California delegates and a majority at the presidential nominating convention. The election was a disaster for the conservatives, but the Goldwater activists now controlled large swaths of the GOP and they had no intention of retreating. The stage was set for a conservative takeover, based in the South and West, in opposition to the Northeast. Ronald Reagan continued in the same theme. George H. W. Bush was more closely associated with the moderates but his son George W. Bush was firmly allied with the conservatives.

Realignment: The South becomes Republican

Before Reconstruction and for a century thereafter, the white South identified with the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party's dominance in the southern states was so strong, the region was called the Solid South. The Republicans controlled certain parts of the Appalachian Mountains,[61] and they sometimes did compete for statewide office in the border states.[62]

Before 1948, the Southern Democrats saw their party as the defender of the Southern way of life, which included a respect for states' rights and an appreciation for traditional southern values. They repeatedly warned against the aggressive designs of Northern liberals and Republicans, as well as the civil rights activists they denounced as "outside agitators". Thus there was a serious barrier to becoming a Republican.[62]

In 1948, Democrats alienated white Southerners in two ways. The Democratic National Convention adopted a strong civil rights plank, leading to a walkout by Southerners. Two weeks later President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981 integrating the armed forces. In 1948 the Deep South walked out, formed a new regional party and nominated J. Strom Thurmond. He carried the Deep South but the outer South stayed with Truman and the "Dixiecrats" returned to the party.

1964–1972

By 1964 the Democratic lock on the South remained strong, but cracks began to appear. One long-term cause was that the region was becoming more like the rest of the nation and could not long stand apart in terms of racial segregation. Modernization brought factories, businesses, and larger cities, and millions of migrants from the North; far more people graduated from high school and college. Meanwhile, the cotton and tobacco basis of the traditional South faded away, as former farmers moved to town or commuted to factory jobs. Segregation, requiring separate dining and lodging arrangements for employees, was a serious obstacle to business development.

The highly visible immediate cause of the political transition involved civil rights. The Civil Rights Movement caused enormous controversy in the white South with many attacking it as a violation of states' rights. When segregation was outlawed by court order and by the Civil Rights acts of 1964 and 1965, a die-hard element resisted integration, led by Democratic governors Orval Faubus of Arkansas, Lester Maddox of Georgia, Ross Barnett of Mississippi, and, especially, George Wallace of Alabama. These populist governors appealed to a less-educated, blue-collar electorate that on economic grounds favored the Democratic Party and supported segregation.[63]

After passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 most Southerners accepted the integration of most institutions (except public schools). With the old barrier to becoming a Republican removed, Southerners joined the new middle class and the Northern transplants in moving toward the Republican Party. Integration thus liberated Southern politics from the old racial issues. In 1963 the federal courts declared unconstitutional the practice of excluding African-American voters from the Democratic primaries, which had been the only elections that mattered in most of the South. Meanwhile, the newly enfranchised black voters supported Democratic candidates at the 85–90% level, a shift which further convinced many white segregationists that the Republicans were no longer the black party.[63]

Southern Strategy

Some critics, most notably Dan Carter, have alleged that the rapid growth in Republican strength in the South came from a secretly coded message to Wallacites and segregationists that the GOP was a racist anti-black party seeking their votes.[64] Political scientists and historians point out, that the timing does not fit the "Southern strategy" model. Nixon carried 49 states in 1972, so he operated a successful national rather than regional strategy but the Republican Party remained quite weak at the local, and state level across the entire South for decades. Matthew Lassiter argues that Nixon's appeal was not to the Wallacites or segregationists, but rather to the rapidly emerging suburban middle-class. Many had Northern antecedents; they wanted rapid economic growth and saw the need to put backlash politics to rest. Lassiter says the Southern strategy was a "failure" for the GOP and that the southern base of the Republican Party "always depended more on the middle-class corporate economy and on the top-down politics of racial backlash." Furthermore, "realignment in the South quote came primarily from the suburban ethos of New South metropolises such as Atlanta and Charlotte, North Carolina, not to the exportation of the working-class racial politics of the Black Belt."[65]

The South's transition to a Republican stronghold took decades and manifested an incremental seepage downward from national to state to local levels.[66] First the states started voting Republican in presidential elections—the Democrats countered that by nominating Southerners who could carry some states in the region, such as Jimmy Carter in 1976, and Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996; however, the strategy narrowly failed with Al Gore in 2000. Then the states began electing Republican senators to fill open seats caused by retirements, and finally governors and state legislatures changed sides.[67]

Georgia was the last state to fall, with Sonny Perdue taking the governorship in 2002. Republicans aided the process with redistricting that protected the African-American and Hispanic vote (as required by the Civil Rights laws), but split up the remaining white Democrats so that Republicans mostly would win.[67] In 2006 the Supreme Court endorsed nearly all of the gerrymandering engineered by Tom DeLay that swung the Texas Congressional delegation to the GOP in 2004. DeLay himself was acquitted on appeal in 2013 of illegally funding the state GOP.

In addition to its white middle class base, Republicans attracted strong majorities from the Evangelical Christian vote (including southern pockets of traditionalist Roman Catholics as in south Louisiana), which had been nonpolitical before 1980.[68] The national Democratic Party's support for liberal social stances such as abortion drove many former Democrats into a Republican Party that was embracing the conservative views on these issues. Conversely, liberal Republicans in the northeast began to join the Democratic Party.

In 1969, in The Emerging Republican Majority, Kevin Phillips argued that support from Southern whites and growth in the South, among other factors, were driving an enduring Republican electoral realignment. Today, the South is again generally solid in state elections, and mostly solid in presidential contests, but now for the Republicans. Exit polls in 2004 showed that George W. Bush led John Kerry 70% to 30% among whites, who constituted 71% of southern voters.[69]

Kerry had a 90% to 9% lead among the 18% of black voters. One-third of the Southerners said they were white evangelicals; they voted for Bush, 80% to 20%.[69] In 2008 Barack Obama carried Florida, North Carolina, and Virginia; in 2010 the GOP regained their losses.

Since the Reagan administration, U.S. presidential elections have been close. However, the Republican presidential candidate won a majority of the popular vote only in 2004, while coming in second in 1992, 1996, 2000, 2008, 2012 and 2016.

Political scientists Nicholas A. Valentino and David O. Sears argue that conventional wisdom concerning partisanship today focuses more on the size of government, national security, and moral issues, while disagreements on racial issues plays a smaller role.[70]

Reagan to Bush: 1980–2008

The Reagan Revolution

Ronald Reagan produced a major realignment with his 1980 and 1984 landslides. In 1980, the Reagan coalition was possible because of Democratic losses in most social-economic groups. In 1984, Reagan won nearly 60% of the popular vote and carried every state except his Democratic opponent Walter Mondale's home state of Minnesota and the District of Columbia, creating a record 525 electoral vote total (out of 538 possible votes). Even in Minnesota, Mondale won by a mere 3,761 votes, meaning Reagan came within less than 3,800 votes of winning in all fifty states.[71]

Political commentators, trying to explain how Reagan had won by such a large margin, coined the term "Reagan Democrat" to describe a Democratic voter who had voted for Reagan in 1980 and 1984 (and for George H.W. Bush in 1988), producing their landslide victories. They were mostly white, blue-collar, and were attracted to Reagan's social conservatism on issues such as abortion, and to his hawkish foreign policy. Stan Greenberg, a Democratic pollster, concluded that Reagan Democrats no longer saw Democrats as champions of their middle class aspirations, but instead saw it as being a party working primarily for the benefit of others, especially African Americans and social liberals.

Reagan reoriented American politics. He claimed credit in 1984 for an economic renewal—"It's morning in America again!" was the successful campaign slogan. Income taxes were slashed 25% and the upper tax rates abolished. The frustrations of stagflation were resolved under the new monetary policies of Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, as no longer did soaring inflation and recession pull the country down. Working again in bipartisan fashion, the Social Security financial crises were resolved for the next 25 years.

In foreign affairs, bipartisanship was not in evidence. Most Democrats doggedly opposed Reagan's efforts to support the Contra guerrillas against the Sandinista government of Nicaragua, and to support the dictatorial governments of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador against Communist guerrilla movements. He took a hard line against the Soviet Union, alarming Democrats who wanted a nuclear freeze, but he succeeded in increasing the military budget and launching the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI)—labeled "Star Wars" by its opponents—that the Soviets could not match.

When Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in Moscow, many conservative Republicans were dubious of the growing friendship between him and Reagan. Gorbachev tried to save communism in the Soviet Union first by ending the expensive arms race with America, then (1989) by shedding the East European empire. Communism finally collapsed in the Soviet Union in 1991.

President George H. W. Bush, Reagan's successor, tried to temper feelings of triumphalism lest there be a backlash in the Soviet Union, but the palpable sense of victory in the Cold War was a success that Republicans felt validated the aggressive foreign policies Reagan had espoused. As Haynes Johnson, one of his harshest critics admitted, "his greatest service was in restoring the respect of Americans for themselves and their own government after the traumas of Vietnam and Watergate, the frustration of the Iran hostage crisis and a succession of seemingly failed presidencies".[72]

Congressional ascendancy in 1994

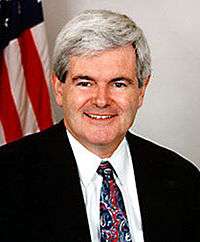

After the election of Democratic President Bill Clinton in 1992, the Republican Party, led by House Republican Minority Whip Newt Gingrich campaigning on a Contract With America, were elected to majorities to both houses of Congress in the Republican Revolution of 1994. It was the first time since 1952 that the Republicans secured control of both houses of U.S. Congress, which, with the exception of the Senate during 2001–2002, was retained through 2006. This capture and subsequent holding of Congress represented a major legislative turnaround, as Democrats controlled both houses of Congress for the forty years preceding 1995, with the exception of the 1981–1987 Congress in which Republicans controlled the Senate.

In 1994 Republican Congressional candidates ran on a platform of major reforms of government with measures such as a balanced budget amendment and welfare reform. These measures and others formed the famous Contract with America, which represented the first effort to have a party platform in an off-year election. The Contract promised to bring all points up for a vote for the first time in history. The Republicans passed some of their proposals, but failed on others such as term limits.

Democratic President Bill Clinton opposed some of the social agenda initiatives but he co-opted the proposals for welfare reform and a balanced federal budget. The result was a major change in the welfare system, which conservatives hailed and liberals bemoaned. The Republican-controlled House of Representatives failed to muster the two-thirds majority required to pass a Constitutional amendment to impose term limits on members of Congress.

In 1995, a budget battle with Clinton led to the brief shutdown of the federal government, an event which contributed to Clinton's victory in the 1996 election. That year, the Republicans nominated Bob Dole, who was unable to transfer his success in Senate leadership to a viable presidential campaign.

The incoming Republican majority's promise to slow the rate of government spending conflicted with the president's agenda for Medicare, education, the environment and public health, eventually leading to a temporary shutdown of the U.S. federal government. The shutdown became the longest-ever in U.S. history, ending when Clinton agreed to submit a CBO-approved balanced budget plan. Democratic leaders vigorously attacked Gingrich for the budget standoff, and his public image suffered heavily.

During the 1998 midterm elections, Republicans lost five seats in the House of Representatives—the worst performance in 64 years for a party that didn't hold the presidency. Polls showed that Gingrich's attempt to remove President Clinton from the office was widely unpopular among Americans; Gingrich suffered much of the blame for the election loss. Facing another rebellion in the Republican caucus, he announced on November 6, 1998 that he would not only stand down as Speaker, but would leave the House as well, even declining to take his seat for an 11th term once he was handily re-elected in his home district.

Neoconservatives

Some liberal Democratic intellectuals in the 1960s and 1970s who became disenchanted with the leftward movement of their party in domestic and foreign policy became "neoconservatives" ("neocons").[73] A number held major appointments during the five presidential terms under Reagan, and the Bushes. They played a central role in promoting and planning the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[74] Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, while not identifying themselves as neoconservatives, listened closely to neoconservative advisers regarding foreign policy, especially the defense of Israel, the promotion of democracy in the Middle East, and the buildup of American military forces to achieve these goals. Many early neoconservative thinkers were Zionists and wrote often for Commentary, published by the American Jewish Committee.[75][76] The influence of the neocons on the White House faded during the Obama years, but it remains a staple in Republican Party arsenal.[77]

The second Bush era

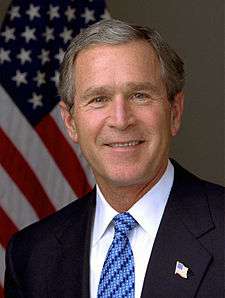

George W. Bush, son of George H. W. Bush, won the 2000 Republican presidential nomination over Arizona Senator John McCain, former Senator Elizabeth Dole, and others. With his highly controversial and exceedingly narrow victory in the 2000 election against the Vice President Al Gore, the Republican Party gained control of the Presidency and both houses of Congress for the first time since 1952. However, it lost control of the Senate when Vermont Senator James Jeffords left the Republican Party to become an independent in 2001 and caucused with the Democrats.

In the wake of the September 11 attacks on the United States in 2001, Bush gained widespread political support as he pursued the War on Terrorism that included the invasion of Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq. In March 2003, Bush ordered for an invasion of Iraq because of breakdown of UN sanctions and intelligence indicating programs to rebuild or develop new weapons of mass destruction. Bush had near-unanimous Republican support in Congress plus support from many Democratic leaders.

The Republican Party fared well in the 2002 midterm elections, solidifying its hold on the House and regaining control of the Senate, in the run-up to the war in Iraq. This marked the first time since 1934 that the party in control of the White House gained seats in a midterm election in both houses of Congress. (Previous occasions were in 1902 and following the Civil War.) Bush was renominated without opposition as the Republican candidate in the 2004 election, and titled his political platform "A Safer World and a More Hopeful America."[78]

It expressed Bush's optimism towards winning the War on Terrorism, ushering in an ownership society, and building an innovative economy to compete in the world. Bush was re-elected by a larger margin than in 2000, but won the smallest share ever of the popular vote for a reelected incumbent president; however he was he first Republican candidate since 1988 to win an outright majority. In the same election that year, the Republicans gained seats in both houses of Congress. Bush told reporters "I earned capital in the campaign, political capital, and now I intend to spend it. It is my style."

He announced his agenda in January 2005, but his popularity in the polls waned and his troubles mounted. Continuing troubles in Iraq, as well as the disastrous government response to Hurricane Katrina led to declining popular support for Bush's policies. His campaign to add personal savings accounts to the Social Security system and make major revisions in the tax code were postponed. He succeeded in selecting conservatives to head four of the most important agencies, Condoleezza Rice as Secretary of State, Alberto Gonzales as Attorney General, John Roberts as Chief Justice of the United States and Ben Bernanke as Chairman of the Federal Reserve.

He failed to win conservative approval for Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court, replacing her with Samuel Alito, whom the Senate confirmed in January 2006. Bush and McCain secured additional tax cuts and blocked moves to raise taxes. Through 2006, they strongly defended his policy in Iraq, saying the Coalition was winning. They secured the renewal of the USA PATRIOT Act.

In the November 2005 off-year elections, New York City, Republican mayoral candidate Michael Bloomberg won a landslide re-election, the fourth straight Republican victory in what is otherwise a Democratic stronghold. In California, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger failed in his effort to use the ballot initiative to enact laws the Democrats blocked in the state legislature. Scandals prompted the resignations of Congressional Republicans House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, Duke Cunningham, Mark Foley, and Bob Ney. In the 2006 midterm elections, the Republicans lost control of both the House of Representatives and Senate to the Democrats in what was widely interpreted as a repudiation of the administration's war policies. Exit polling suggested that corruption was a key issue for many voters.[79] Soon after the elections, Donald Rumsfeld resigned as secretary of defense, to be replaced by Bob Gates.

In the Republican leadership elections that followed the general election, Speaker Hastert did not run and Republicans chose John Boehner of Ohio for House Minority Leader. Senators chose whip Mitch McConnell of Kentucky for Senate Minority Leader, and chose their former leader Trent Lott as Senate Minority Whip by one vote over Lamar Alexander, who assumed their roles in January, 2007. In the October and November gubernatorial elections of 2007, Republican Bobby Jindal won election for governor of Louisiana, Republican incumbent Governor Ernie Fletcher of Kentucky lost, and Republican incumbent Governor Haley Barbour of Mississippi won re-election.

With President Bush ineligible for a third term and Vice President Dick Cheney not pursuing the party's nomination, Arizona Senator John McCain quickly emerged as the Republican Party's presidential nominee, receiving President Bush's endorsement on March 6, six months before official ratification at the 2008 Republican National Convention. On August 29, Senator McCain announced Governor Sarah Palin of Alaska as his running-mate, making her the first woman on a Republican Presidential ticket; McCain surged ahead of Obama in the national polls following the nomination. Amid a financial crisis and a serious economic downturn, however, McCain and Palin went on to lose the election to Democrats Barack Obama and running mate Joe Biden. Since 1992, the 2012 presidential election was the sixth consecutive election in which the Republican candidate failed to win at least 300 electoral votes, suggesting a ceiling on GOP strength and a modicum margin of error should an election become highly competitive.[80]

Challenging the Obama administration: 2009–2016

Following the 2008 elections, the Republican Party, reeling from the loss of the presidency, Congress, and key state governorships, was fractured and leaderless.[81] Michael Steele became the first black chairman of the Republican National Committee, but was a poor fundraiser and was replaced after numerous gaffes and missteps.[82] Republicans suffered an additional loss in the Senate in April 2009, when Arlen Specter switched to the Democratic Party, depriving the GOP of a critical 41st vote to block legislation in the Senate. The seating of Al Franken several months later effectively handed the Democrats a filibuster-proof majority; however, it was short-lived, as the GOP took back its 41st vote when Scott Brown won a special election in Massachusetts in early 2010.

Republicans strongly opposed Obama's 2009 economic stimulus package and 2010 health care reform bill. The Tea Party movement, formed in early 2009, provided a groundswell of conservative grassroots activism to oppose policies of the Obama administration. With an expected economic recovery being criticized as sluggish, the GOP was expected to make big gains in the 2010 midterm elections. However, establishment Republicans began to see themselves at odds with Tea Party activists, who sought to run conservative candidates in primary elections to defeat the more moderate establishment-based candidates. Incumbent senators such as Bob Bennett in Utah and Lisa Murkowski in Alaska lost primary contests in their respective states.

Republicans won back control of the House of Representatives in the November general election, with a net gain of 63 seats, the largest gain for either party since 1948. The GOP also picked up six seats in the Senate, falling short of retaking control in that chamber, and posted additional gains in state governor and legislative races. Boehner became Speaker of the House while McConnell remained as the Senate Minority Leader. In an interview with National Journal magazine about congressional Republican priorities, McConnell explained that "the single most important thing we want to achieve is for (Barack) Obama to be a one-term president".[83]

In February 2011, several freshmen Republican governors began proposing legislation that would diminish the power of public employee labor unions, by removing or negatively affecting their right to collective bargaining, claiming that these changes were needed to cut state spending and balance the states' budgets. These actions sparked public-employee protests across the country. In Wisconsin, the veritable epicenter of the controversy, Governor Scott Walker fought off a labor-fueled recall election, becoming the first state governor in U.S. history to defeat a recall against him.

2012 to 2016

.jpg)

After leading a pack of minor candidates for much of 2010 and 2011, former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney, despite outmatching his opponents in both money and organization, struggled to hold on to his lead for the 2012 GOP nomination. As the presidential campaign season headed toward the voting stage in January 2012, one candidate after another surged past Romney, held the lead for a few weeks, then fell back. According to the RealClearPolitics 2012 polling index, five candidates at one time or another were the top choice of GOP voters: Texas Governor Rick Perry, motivational speaker Herman Cain, former Speaker Newt Gingrich, former Senator Rick Santorum, and Romney himself.[84]

After losing to Santorum in Iowa and Gingrich in South Carolina, Romney racked up a number of wins in later contests, emerging as the eventual frontrunner after taking the lion's share of states and delegates in the crucial Super Tuesday contests, despite an embarrassing loss in the Colorado caucuses, and near-upsets in the Michigan and Ohio primaries. Romney was nominated in August and chose Congressman Paul Ryan, a young advocate of drastic budget cuts, as his running mate. Throughout the summer polls showed a close race. Romney had a good first debate but otherwise had trouble reaching out to ordinary voters. He lost to Obama 51% to 47%. Instead of gaining in the Senate as expected, Republicans lost seats.

The party mood was glum in 2013. One conservative analyst concluded:

It would be no exaggeration to say that the Republican Party has been in a state of panic since the defeat of Mitt Romney, not least because the election highlighted American demographic shifts and, relatedly, the party's failure to appeal to Hispanics, Asians, single women and young voters. Hence the Republican leadership's new willingness to pursue immigration reform, even if it angers the conservative base.[85]

In March 2013, National Committee Chairman Reince Priebus gave a stinging postmortum on the GOP's failures in 2012, calling on the party to reinvent itself and to endorse immigration reform. He said, "There's no one reason we lost. Our message was weak; our ground game was insufficient; we weren't inclusive; we were behind in both data and digital; and our primary and debate process needed improvement." He proposed 219 reforms, including a $10 million marketing campaign to reach women, minorities and gays; a shorter, more controlled primary season; and better data collection and research facilities.[86]

The party's official opposition to same-sex marriage came under attack.[87][88] Meanwhile, social conservatives such as Rick Santorum and Mike Huckabee remained opposed to same-sex marriage and warned that evangelicals would desert if the GOP dropped the issue.[89] Many leaders from different factions spoke out in 2013 on the need for a new immigration policy in the wake of election results showing a sharp move away from the GOP among Hispanics and Asians. However the Republicans in Congress could not agree on a program and nothing was done.[90] Republicans in Congress forced a government shutdown in late 2013, after narrowly averting similar fiscal crises in 2011 and 2012.

The Tea Party fielded a number of anti-establishment candidates in the 2014 Republican primaries, but scored very few notable wins. However, they managed to unseat House Majority Leader Eric Cantor in his Virginia primary race. GOP attacks on Obama's unpopular administration resonated with voters, and the party posted major gains around the country. They regained control of the Senate, and increased their majorities in the House to the highest total since 1929. They took control of governorships, state legislatures and Senate seats in nearly all Southern states, except Florida and Virginia.[91]

Great divisions in the House GOP conference were apparent after the 2014 midterm elections, with conservative members, many of them from the right-leaning Freedom Caucus, expressing dissatisfaction with congressional leadership. John Boehner's surprise announcement in September 2015 that he would step down as Speaker sent shockwaves through the House. After Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy bowed out of the race to replace Boehner due to a lack of support, House Ways and Means Chair Paul Ryan announced he would run, with the Freedom Caucus' support. Ryan was elected Speaker on October 29.